|

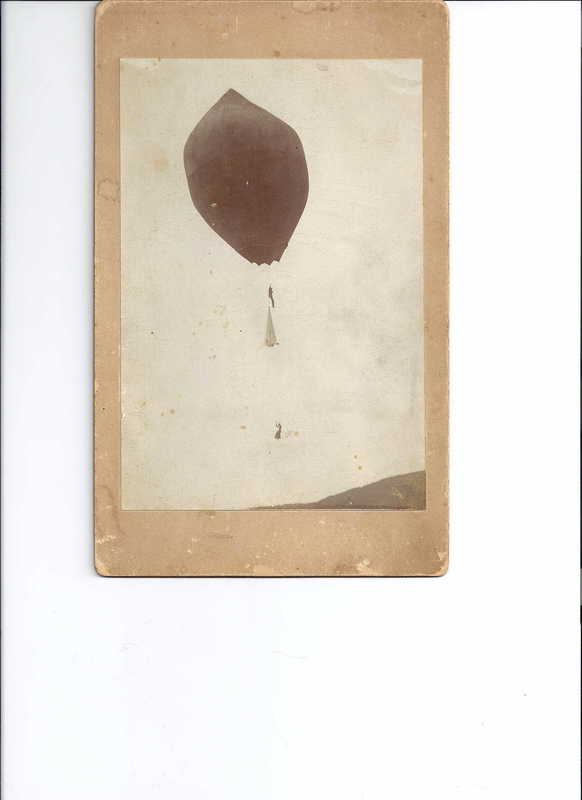

Above: Photo of "Lady Parachutist" and Eugene McCarthy, caught in the lines of a hot air balloon and carried aloft at a country fair, Waitsfield Vermont, September 1896

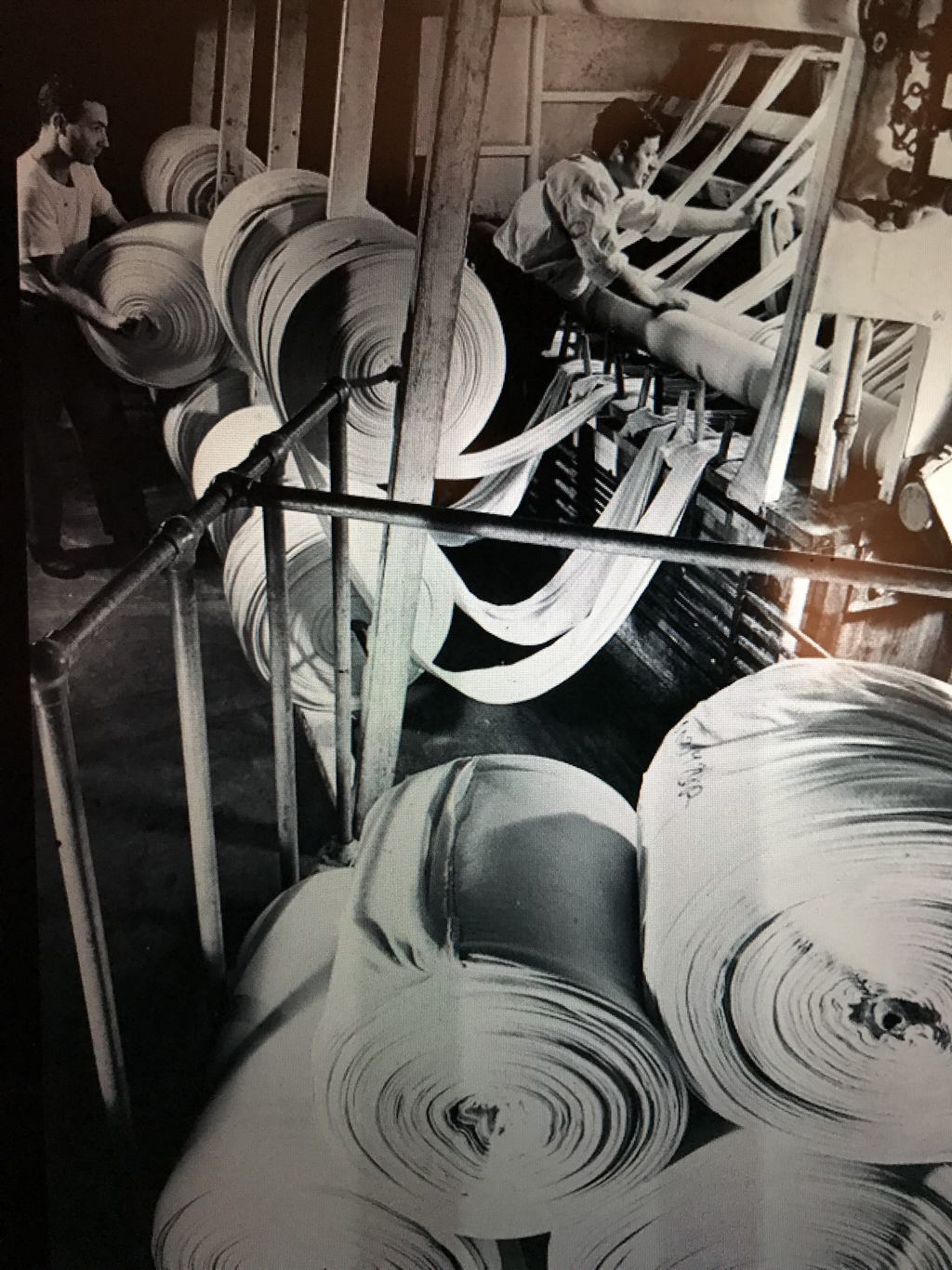

In September 1896, Eugene McCarthy [often spelled McCarty], dairy farmer in Waitsfield Vermont took an involuntary hot air balloon ride that was captured on film. According to the "History of Waitsfield Vermont 1789-2000" by Richard M. Bisbee, "It seems, in 1896, Gene McCarty went to the fair with four of his six children. He became a volunteer with the balloon launching. In the process, as the balloon began to rise, Gene McCarty got tangled in the line and grabbed the ropes above and soon found himself 3,000 feet in the air, but he hung on. 'Far over Bald Mountain he surveyed the scenery which showed the Montreal mountains, the White peaks in New Hampshire, the whole sweep of Vermont…….' Finally the hot smoky air in the balloon bag cooled and began to descend taking him 'half a mile from the park behind a clump of trees in Fayston Valley.' Gene McCarty started walking immediately back to the Fair grounds, gathered up his children and drove the horse and wagon home." (the quotes in this excerpt are from a 1964 article about the incident in the Burlington Free Press newspaper) The photo above is in my family. According to the note written on the back by Gene McCarthy's niece, "he caught his foot in a rope as the balloon started up with lady parachutist. He landed safely while his family was frantic at his experience. He died about two years later of pneumonia." Family legend is that the trauma of the experience weakened him so that he died a few years later, in 1899, at age 45. Upon the death of the man of the house, his wife and younger kids, including my great grandfather Florence, sold the farm and moved to the mill town of Lawrence, Mass. According to family history, the last straw that caused the family to give up the farm and move to Lawrence was the barn burning down. Below: Reverse side of photo including note

1 Comment

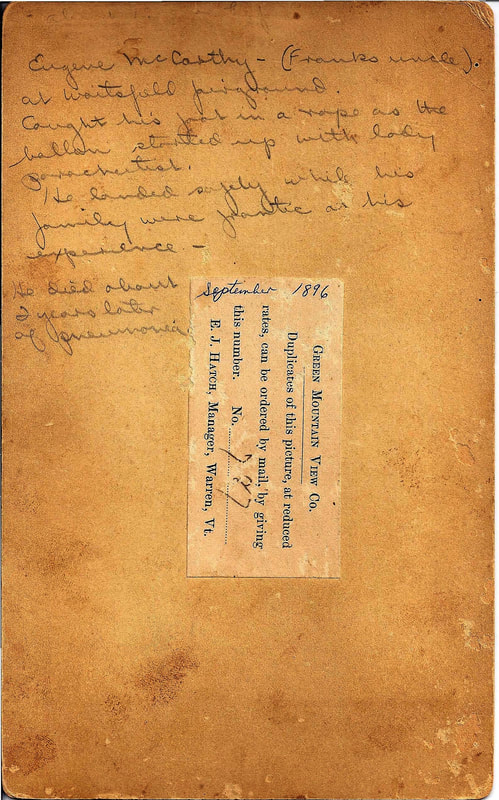

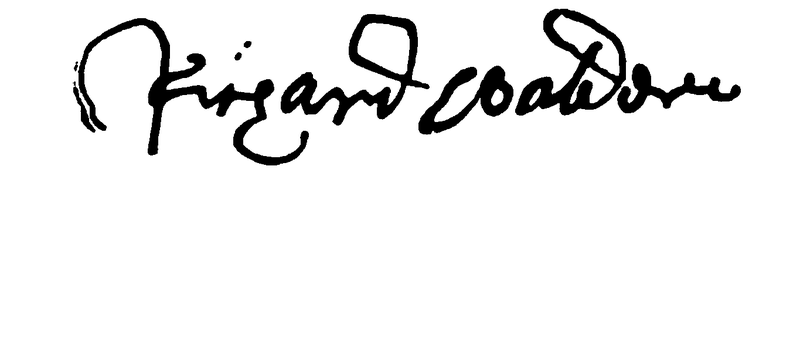

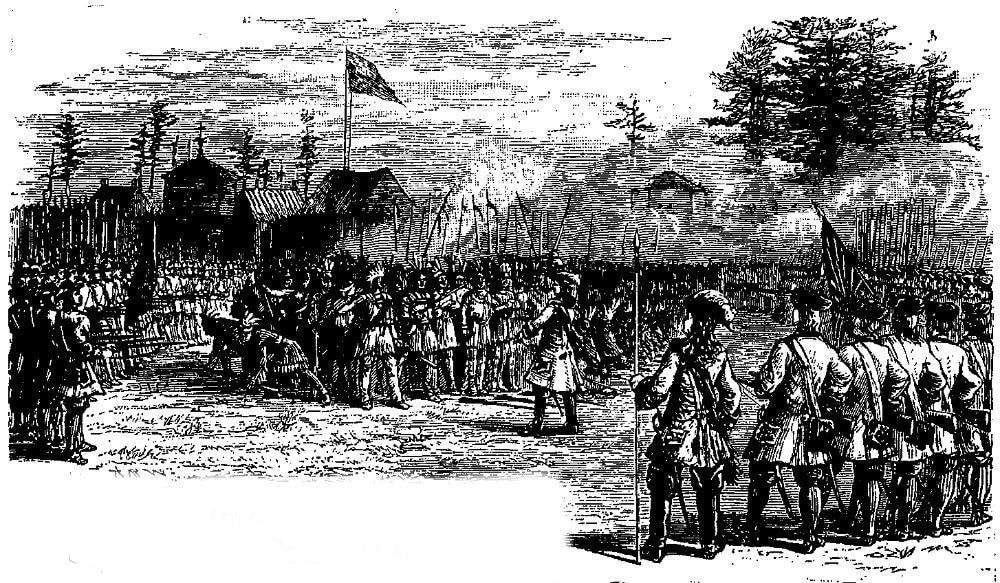

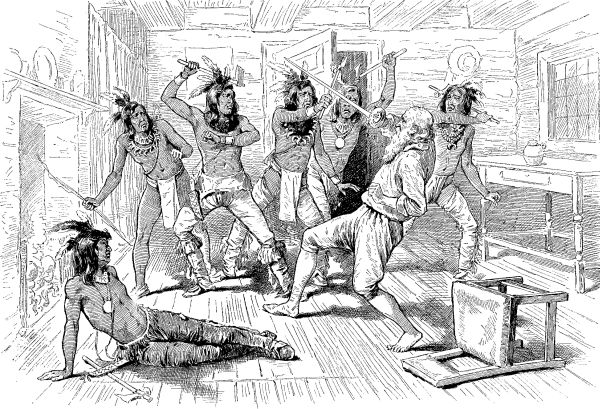

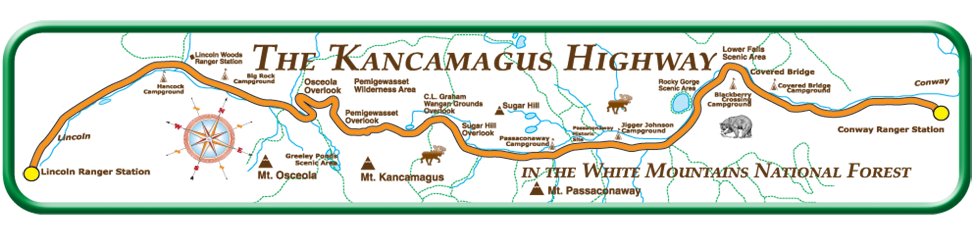

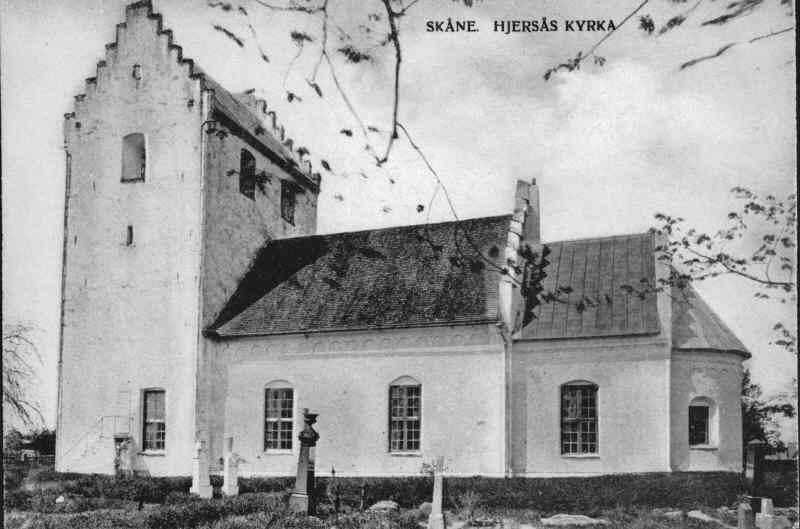

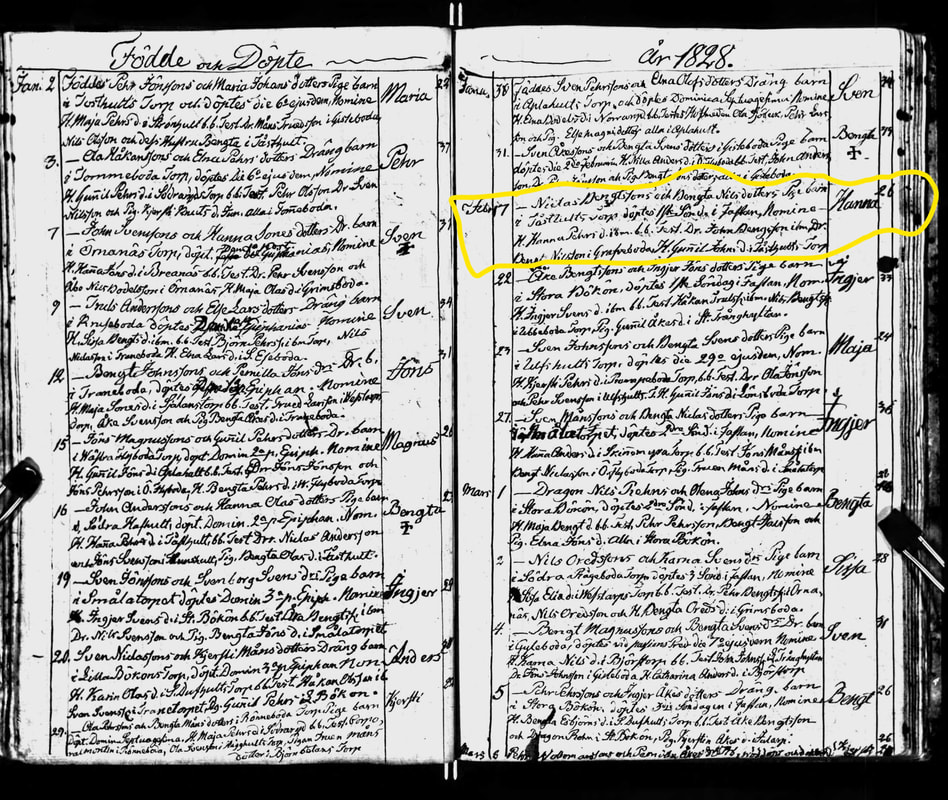

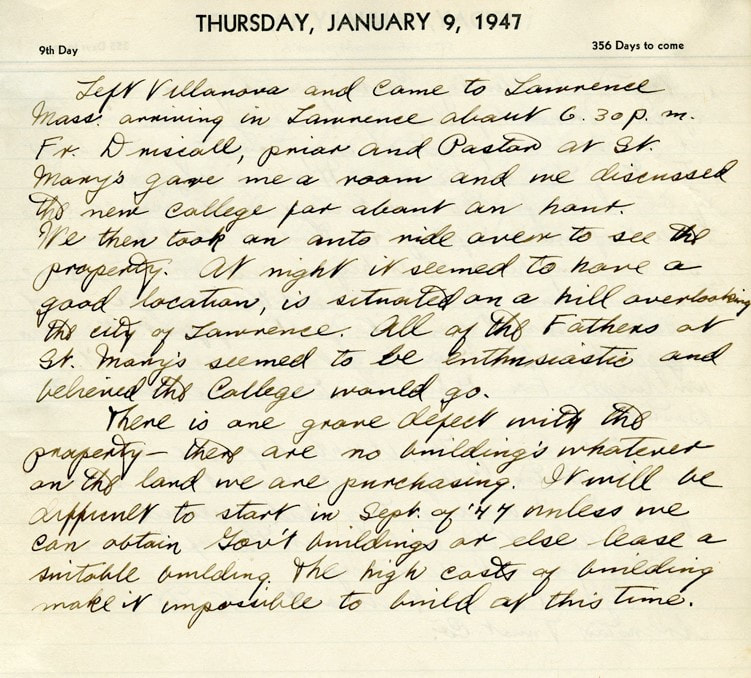

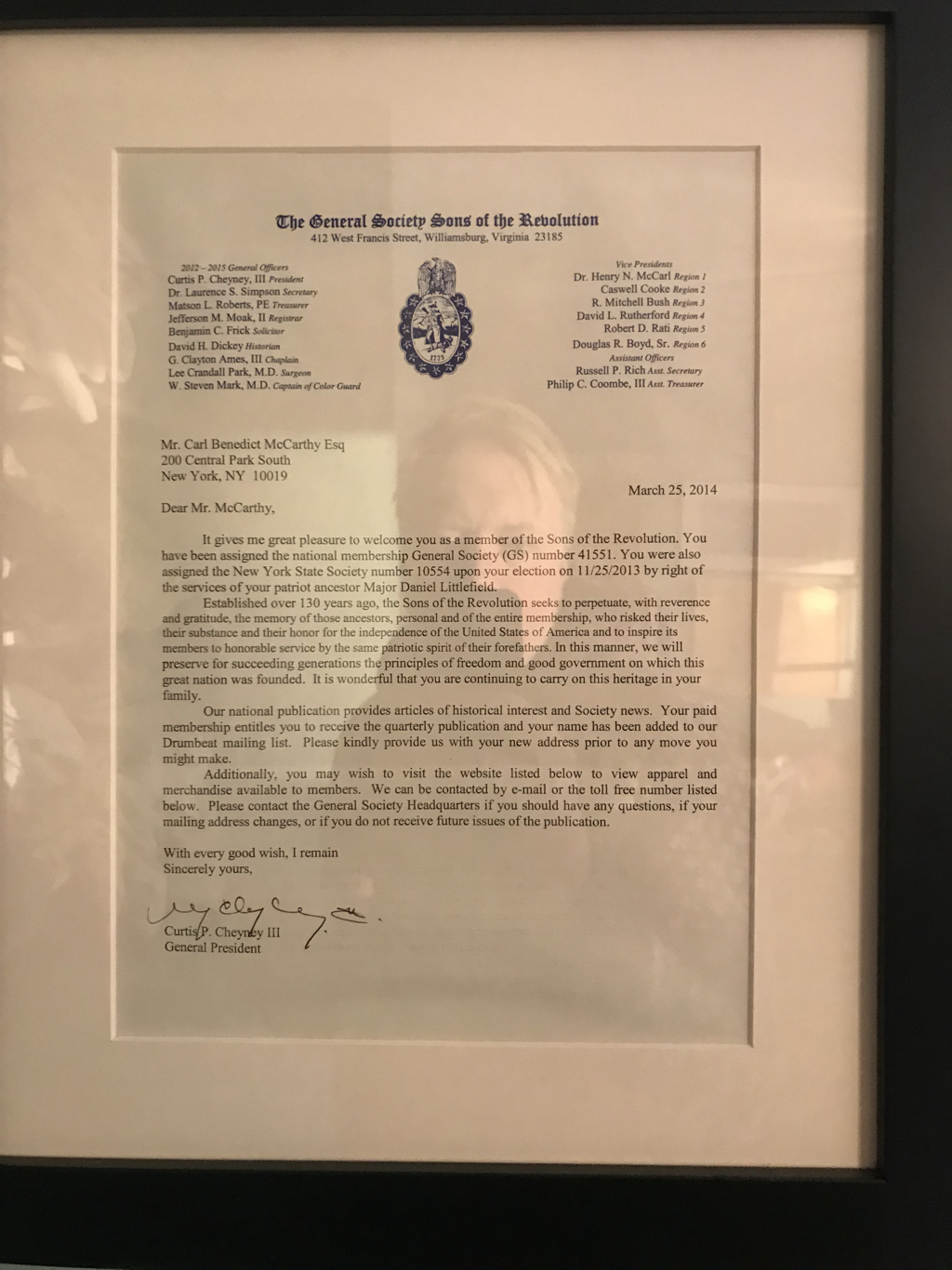

The Assassination of Major Richard Waldron by Kancamagus, last Sachem of the Pennacook Indians1/20/2018 Background The broad strokes of the story are already intriguing: First, we have an imperious colonial captain, Richard Waldron (or Walderne) who rules his frontier trading post at Cocheco (in modern-day Dover, New Hampshire) as his own personal fief. Although the towns of Hampton, Portsmouth, Exeter and Dover have temporarily come under Massachusetts jurisdiction (see Old Norfolk in the Glossary), this is an area where some settlers have claims to great tracts of land, Waldron being one of them. He gains notoriety for his treatment of Quaker missionaries to this area in 1662. He forces them to march eighty miles through the area in the dead of winter, having them publicly whipped every ten miles. Our chronologer of the area, John Greenleaf Whittier, covered it in one of his poems: Bared to the waist, for the north wind's grip And keener sting of the constable's whip, The blood that followed each hissing blow Froze as it sprinkled the winter snow. Waldron is also known for sharp practices ripping off his native American trading partners. For example, when they catch him putting his hand on the scales, he tells them his fist weights exactly a pound so they are not being deceived. The Indians nevertheless return to his post because of its proximity and convenience, and his supply of useful wares. Then we have Kancamagus, grandson of Passaconnway, great sachem of the Pennacooks. In 1684, he appears on the scene, writing a letter to the governor, in which he calls himself John Hogkins, asking for protection against the Mohawks, ancient enemies of the New England indians. Whether the governor provided protection is not known. In any case, Kancamagus a.k.a. John Hogkins forswears the peaceable ways of Wonalancet, his uncle. In 1689, he vows to stand up to the English. Because there are barely any Pennacooks left to lead, he leads an alliance with the natives of the Androscoggin River valley. Waldron in King Philip's War In the native uprising of 1675 known as King Philip's War, Major Waldron signed a peace treaty with the local sachem, the hapless Wonalencet. Below: The signature of Richard Walderne a.k.a. Waldron As a gesture of peace after the treaty, in September 1676, Waldron invites his Pennacook trading partners into a playing a "game" with the company of men he commands. However, it's actually a trap. He proposes a mock "battle", in which the Indians are given a canon to use, with powder but no shot. While they are awed and distracted by this device, the 400 natives are surrounded by four companies of colonial men, and disarmed. The Indians are then sorted, with the individuals known to be peaceable -- such as Christian converts living in the Praying Towns along the Merrimack -- allowed to go free. The remaining two hundred Indians are imprisoned and sent to Boston for trial. Seven are hanged for treason and the remainder are sold into slavery in Barbados. Some accounts say Wonalencet himself was transported to Barbados, but managed to make his way back home. In any case, the authority of Wonalancet was shattered, and eventually his nephew Kancamagus took up the mantle of "sachem" of the Pennacooks. Below: A nineteenth century illustration of the "Deceit of Captain Waldron" wherein the Indians are surrounded and captured. According to a 1989 commemoration of the 300th Anniversary of the "Cocheco Massacre", the event took place in a field where the parking lot for Aubuchon Hardware currently is. Waldron in King William's War: The "Crossing Out of the Account" Fast-forward thirteen years. There is a new war between the English and the natives, known as King William's War. (See the Glossary.) Captain Richard Waldron is now Major Richard Waldron. He is an old man of means and status. For example, he had been the second president of the Royal Council of New Hampshire, a governing body created by the separation of Old Norfolk from Massachusetts. His trading post, on the Cocheco River, is comprised of five garrison houses. He is warned that a large band of natives have assembled at Pennacook (modern-day Concord, New Hampshire), with the intent of attacking him. They are led by Kancamagus, who vows to avenge the false hospitality and deception that led to the destruction of his tribe. Below: A surviving garrison house from the 1670s, photographed in the mid-nineteenth century When warned about the threat, Major Waldron is dismissive. He is supposed to have said "let them go plant their pumpkins" --- which I guess means "go about your business and don't worry about it". On the night of June 27, 1689, according to the Indians' plan of attack, two squaws requested permission to lodge in each garrison at Cocheco. This was apparently a common practice, to grant lodging to local Indians known to the colonists. "No fear was discovered among the English, and the squaws were admitted. One of those admitted into Waldron's garrison, reflecting, perhaps, on the ingratitude she was about to be guilty of, thought to warn the Major of his danger. She pretended to be ill, and as she lay on the floor would turn herself from side to side, as though to ease herself of pain that she pretended to have. While in this exercise she began to sing and repeat the following verse: O Major Waldon, You great Sagamore, O what will you do, Indians at your door! No alarm was taken at this, and the doors were opened [by the native women] according to their plan, and the enemy rushed in with great fury. They found the Major's room as he leaped out of bed, but with his sword he drove them through two or three rooms, and as he turned to get some other arms, he fell stunned by a blow with the hatchet. They led him into his hall and seated him on a table in a great chair, and then began to cut his flesh in a shocking manner. Some in turns gashed his naked breast, saying, "I cross out my account." [meaning, our account is now settled.] Then, cutting a joint from a finger, would say, " Will your fist weigh a pound now'!'' His nose and ears were then cut off and forced into his mouth. He soon fainted, and fell from his seat, and one held his own sword under him, which passed through his body, and he expired. The family were forced to provide them a supper while they were murdering the Major.” (From: The History of the Great Indian War of 1675 and 1676, Commonly Called King Philips War by Thomas Church (Hartford, 1851)(ed. Samuel G. Drake)). Below: A nineteenth century depiction of the assassination of Major Waldron. Kancamagus disappeared into the wilderness of the Androscoggin valley, along with twenty-nine captives to be held for ransom. Vengeance had been served. And so ends the tale of Major Waldron. Or does it? Interpreting and Analyzing the Story The "crossing out of the account" is a compelling narrative of deceit and retaliation. If you go further into the details, though, it is also important for illustrating how personal these battles (to the death) between English and Indians were. Generally speaking, the attackers were not anonymous natives from afar. Everyone was known to everyone. And whole families were involved, with both sides capturing the others' wives and children to use as bargaining chips. This led to cycles of violence and retribution. For example, Captain Charles Frost of Kittery, who commanded one of the four companies that captured the indians in Waldron's deceit in 1676, was hunted down and assassinated in Eliot, Maine on July 4, 1697. Frost himself had been inspired to treat the natives with hostility by an attack on his family in 1650, in which his mother and sister were killed. Perhaps the most famous case of a cycle of personal vengeance was Jeremy Moulton's. At the age of four, his parents were killed and he was captured in the devastating 1692 raid on York, Maine, probably the most destructive Indian raid in New England. Fast forward to 1724, and he was leading the successful attack on Father Sebastian Rale, the French Jesuit missionary who instigated the attacks, killing him and many Indians at present-day Norridgewock, Maine. In other cases, the connection was one of mutual mercy instead of mutual retribution. According to Cotton Mather’s Magnalia Christi Americana [a.k.a. Ecclesiastical History of New England], Elizabeth Heard was a witness to Waldron’s deceit in 1676, and there she sheltered a young native Abenaki boy from death. On the night of the Cocheco Massacre, an Indian pointed his musket at her, but suddenly spared her life because of the recognition of who she was. Her house, defended by William Wentworth because her husband had recently died, was not invaded. Among the twenty nine captives taken during the Cocheco Massacre were Sarah Gerrish, the 7 year old granddaughter of Major Waldron, and Esther Lee, daughter of Richard Waldron along with her (presumably infant) child. Lee's husband was killed in the raid, and her infant child did not survive captivity. She and the little girl Gerrish her niece were both ultimately returned to Dover in a prisoner exchange. The use of family members as captives ultimately led to the downfall of Kancamagus. In September 1690, an English force under the command of Capt. Benjamin Church located and attacked Kancamagus’s village on the Androscoggin River. Somehow, Kancamagus was able to escape the attack, but his family wasn’t so lucky. His sister was slain and his brother-in-law, wife and children were taken captive, although his brother-in-law was later able to escape. Captain Church took the captives to Wells, Maine, where they were used to try to lure Kancamagus to the peace table. In response to the attack on his village and the capture of his family, Kancamagus launched an attack on Church at Casco, Maine, on Sept. 21. After a great deal of hard fighting, which resulted in the death of seven of Church’s men and 24 wounded, Kancamagus was beaten back. With the English still holding his family hostage, Kancamagus was forced to make peace with the English at Wells. Following this agreement of peace, Kanacamagus was reunited with his family. After 1692, little is written about Kancamagus. It’s possible that once he recovered his family, he continued to fight alongside other Abenaki people, although that is purely speculation. His name lives on in the scenic road well-loved by leaf peepers. However, I'm sure that, as tourists drive the Kancamagus Highway, they have scant knowledge of the story of his life. Above: map of the Kancamagus Highway. Source: http://kancamagushighway.info/Below: My Swedish immigrant forebears in their farmhouse in Kingman, Maine circa 1910. Hanna is to the far right, her son my great grandfather Martin Johnson (originally Carlsson) is to the far left and the woman to the right of him is my great grandmother Marie Jensen. The boy on Martin's lap is his son Martin, who died in 1911 at age 10 of Hodgkins Disease. He died in the same house in Lawrence, Mass. where his sister, my grandmother, was born eight months later. I posted a picture of that house on Kingston Street in another blog post. On August 25, 1892, my great great grandmother Hanna Niklasdotter Jönsson departed her hometown of Hjärsås, Sweden, where she had been living, presumably since she married Carl Jönsson of that town on July 8, 1858. She would have been 64 years old. Below: Photo from the 1800s of the Hjärsås parish church. Her travel record in the parish record book states that she was traveling with her daughter Anna, age 26, unmarried. Their destination was listed as Kingman, Maine, meaning some other relative, presumably her husband Carl, had gone before them to buy a farm there. Why they did not end up in New Sweden, the swedish settlement up in Aroostook County, Maine, is unknown. Instead, they bought a farm in rapidly depopulating Kingman, Maine, probably for a song. As I explained in my review of the book Yankee Exodus, after the Erie Canal opened, the upland parts of New England rapidly depopulated. This was because cheap grain could come from the fertile lands of the Ohio Valley to New England by boat, making farming in places like Maine very uneconomical. Whatever Yankee farmer sold my Swedish ancestors this farm probably counted his lucky stars. Then he likely got on the next train to Oregon Country to seek his fortune in the west. Within a few years my ancestors had abandoned farming in Maine and moved to the mill town. Below: Birth record of Hanna Niklasdotter, Ignaberga, Sweden, 1828 Until I learned about Hanna's illegitimate daughter, born before she married Carl Jönsson, the most interesting thing going on from a genealogical perspective was that some of her children kept the Swedish naming convention, and called themselves Carlsson or Carlsdotter, while others (including my great grandfather), took their father's last name, Jönsson, as their own thus making it a family name. This led to some confusion for a while when doing research, and for many years I didn't realize my great grandather Martin Johnson (he even took the extra step of anglicising Jönsson) had a brother who went by John Carlson (anglicized from Carlsson). Then in 2011, I got the following message from another ancestry.com user: "Hi, Your Hanna C. is Hanna Niklasdotter, born in Örkened, Kristianstad, Sweden on 17 Feb 1828. Hanna's first daughter was Pernilla Persdotter (born outside of marriage in Hjärsås, Kristianstad on 2 Feb 1853) - She [pernilla] later married Andrew Johnson in Mananna, Meeker County, Minnesota in 1889 - Andrew was the sponsor of my wife's grandmother (father's mother), Ellen (Olson) Nelson.) Yours truly, Adolph Johnson" Since then, the descendants of Pernilla, the illegitimate daughter (and therefore my half-cousins) have invited me to their family reunions in Minnesota. Unfortunately I haven't been able to attend. Swedish society was apparently under a lot of stress in the latter half of the nineteenth century, with the old agrarian structures breaking down and a lot of income disparity. Pernilla also had a child out of wedlock, Nils, before she emigrated from Sweden and then had one more (Julius) with Andrew Johnson after their marriage. Below: More photos taken that day in Maine around 1910. The far right shows Hanna with her three children who had emigrated with her, Martin, Anna and John. She had a daughter Ingrid who emigrated to Denmark. She also had a daughter Lissa. Lissa arrived in Boston on 9 Aug 1888. She had left Dönaberga, Hjärsås, Kristianstad, Sweden on 13 Apr 1887. Not sure why there was such a delay between leaving her parish and arriving in Boston. I have not been able to locate her after arrival. Was she already deceased by the time of the family reunion in Kingman, Maine shown in these photos? Above: men working in a dyehouse, 1940s Poem 38 Mill Work (a mock poem testimony) by Rich McCarthy, 2011 I was a Lawrence High School student in the 40s. The mills were humming: The Wood Mill, the Ayer Mill, the Arlington, the Pacific. Most every kid had a parent or relative working in a mill. My grandfather had been a weaver here Since he left Vermont at age nineteen (When his father died and the barn burned down.) [My note: the death of his father after a balloon accident is covered in another blog post.] In High School The worst the future could hold for us Was to end up in a mill after graduation We joked about becoming a mill rat. . . no way. My poor dad was a mill rat... in the dye house. And what did I do after I graduated. I took a job. Where? In a dye house. Like dad, I became a “jig” operator It wasn’t bad work; Except for the fumes: The hydrochloric acid, the ammonia, and the formaldrahyde fumes... Whew, sometimes it was overwhelming. I met some interesting people, Like the guy who never wore a shirt And had blue birds tattooed on his chest, One on each breast. Flying towards each other. I only lasted for two months. It wasn’t for me, a kid. I didn’t have to support a family. I left for a job with a magazine distributor. I was out of the mill. It was clean work: Putting up orders for drug stores. But the pay, 65 cents an hour, Stunk So what did I do? I went back to the mill. (The American Woolen Company) One buck an hour? I couldn’t believe it With benefits to boot! A Union shop, the CIO. So there I was, A back-boy Working the second shift, (two to ten), In the mule spinning room. The temperature was hot And humid. . . 90 degrees plus Humidifiers keeping it moist So the ends would not fall. The sweat poured over our brows We all wore head bands To keep it out of the eyes It was so hot we wore pants cut off at the knee, That’s all, no shirt, bare backed And old shoes with no socks It was a nice place to be in a winter storm, tropical. Cockroaches abounded. I stuck it out for about a year. The mills were shutting down, Moving south Where cheaper labor could be found, Or so we heard. So I got “laid off". .. permanently. Lawrence fell into hard times. The textile industry, as Lawrence knew it, Collapsed. But the experience taught me About organized labor, unions. I had got a decent wage. Because the job was so dirty, We were allowed a shower On company time at shift’s end. Because of the union, When we cleaned rollers, The machinery was disengaged. (Back-boys had been killed in prior years, Crushed to death when switches Were accidentally pulled.) Funny, as I think of it, I never heard of the strike of 1912 Not from my working stiff relatives, not in school. So I’m glad this is not the case today In Lawrence. And that we now celebrate The gutsy spontaneous reaction Of exploited immigrants Who made a better future for mill workers... All workers. And I might say, for me personally, A kid back in 1949. Below: The Wood Mill and the Ayer Mill at night, south bank of the Merrimack River, Lawrence, Mass., 1940s

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed