|

Native American History and Poetic License (a long read) Once upon a time, so the story goes, about 1628 – right when the English puritans were beginning to arrive to claim their promised land around Massachusetts Bay – there was a wedding of a native princess. She was the daughter of Passaconaway, the great Bashaba of the Pennacooks. The Pennacooks were the natives of the Merrimack Valley. Their domains extended from present day Haverhill all the way up to its headwaters along the Pemigewasset. The Bashaba made his home at a curve in the river, called Pennacook, site of present day Concord N.H. The tribe and affiliated bands of natives – Wachusetts, Agawams, Wamesits, Pequawkets, Pawtuckets, Nashuas, Namaoskeags, Coosaukes, Winnepesaukes, Piscataquas, Winnecowetts, Amariscoggins, Newichewannocks, Sacos, Squamscotts, and Saugusaukes – also met at prescribed times at various sites along the river, usually to fish: for example, at the falls at Amoskeag, later the source of waterpower for the mills at Manchester, N.H.; Pawtucket, later the source of waterpower for the mills at Lowell; and at Pentucket, later called Haverhill. According to a 1981 book on the Forgotten Salmon of the Merrimack, there were fourteen sets of falls on the mainstream of the Merrimack River, including on the Pemigewasset, where natives could have fished for salmon. The natives also met each year at the Weirs, fish traps designed to catch a bountiful harvest flowing out of swollen Lake Winnipesauke. This is where she met her groom, known as Ahquedaukenash (meaning "dams" or "stopping-places"). In the present day it’s called Weirs Beach. The groom was Montowampate, son of the “Squaw Satchem”, the female leader of the coastal Saugus Indians who took over when her husband Nanepashemet was killed battling their rivals, the Tarrantines, on August 8, 1619 in present day Ipswich, Massachusetts. How do we know any of this? From written records of English settlers mainly, and retellings of the story. The English settlers tell the stories of the Indians Passaconnaway and Sagamore James, as he was known to the English, were undoubtedly historical figures who signed deeds and, in the case of the latter, sought redress from English authorities to protect his interests and who is described as wearing English clothes. “Sagamore James went to Governor Winthrop on March 26, 1631, in order to recover twenty beaver skins of which he had been defrauded by an Englishman named Watts.” I hope to write more on the historical record left by natives in English colonial society, particularly the descendants of Nanepashemet who regularly tried to use the English courts to protect their land rights, in another blog entry. The first telling of the wedding story of this (yet unnamed) princess, daughter of Passaconaway, was by Thomas Morton, founder of the ill-fated Merrymount Colony. “The Sachem or Sagamore of Saugus made choice, when he came to man's estate, of a lady of noble descent, daughter to Papasiquineo [another name for Passaconnaway], the Sachem or Sagamore of the territories near Merrimack river, a man of the best note and estimation in all those parts, and (as my countryman Mr. Wood declares in his prospect) a great Necromancer; this lady the young Sachem with the consent and good liking of her father marries, and takes for his wife. Great entertainment he and his received in those parts at her father's hands, where they were feasted in the best manner that might be expected, according to the customs of their nation, with reveling and such other solemnities as is usual amongst them. The solemnity being ended, Papasiquineo causes a selected number of his men to wait upon his daughter home into those parts that did properly belong to her Lord and husband; where the attendants had entertainment by the Sachem of Saugus and his countrymen: the solemnity being ended, the attendants were gratified. Not long after the new married lady had a great desire to see her father and her native country, from whence she came; her Lord willing to please her, and not deny her request, amongst them thought to be reasonable, commanded a selected number of his own men to conduct his lady to her father, where, with great respect, they brought her, and, having feasted there a while, returned to their own country again, leaving the lady to continue there at her own pleasure, amongst her friends and old acquaintance, where she passed away the time for a while, and in the end desired to return to her Lord again. Her father, the old Papasiquineo, having notice of her intent, sent some of his men on embassy to the young Sachem, his son-in-law, to let him understand that his daughter was not willing to absent herself from his company any longer, and therefore, as the messengers had in charge, desired the young Lord to send a convoy for her, but he, standing, upon terms of honor, and the maintaining of his reputation, returned to his father-in-law this answer, that, when she departed from him, he caused his men to wait upon her to her father's territories, as it did become him; but, now she had an intent to return, it did become her father to send her back with a convoy of his own people, and that it stood not with his reputation to make himself or his men too servile, to fetch her again. The old Sachem, Papasiquineo, having this message returned, was enraged to think that his young son-in-law did not esteem him at a higher rate than to capitulate with him about the matter, and returned him this sharp reply; that his daughter's blood and birth deserved more respect than to be so slighted, and, therefore, if he would have her company, he were best to send or come for her. The young Sachem, not willing to undervalue himself and being a man of a stout spirit, did not stick to say that he should either send her by his own convey, or keep her; for he was determined not to stoop so low. So much these two Sachems stood upon terms of reputation with each other, the one would not send her, and the other would not send for her, lest it should be any diminishing of honor on his part that should seem to comply, that the lady (when I came out of the country) remained still with her father; which is a thing worth the noting, that savage people should seek to maintain their reputation so much as they do.” So when Thomas Morton “came out of the country” in 1629 (a euphemism for “getting expelled by puritans”), the bride apparently was still stuck up the Merrimack away from her groom, because nobody would escort her back down to Saugus. Later tellings of the story give her a definitive identity, Wenunchus. Alonzo Lewis, in his 1829 history of the town of Lynn (including Lynnfield, Saugus, Swampscott and Nahant, all of which were set off from Lynn), gives her this name… and also completes the story, sort of: “My lady readers will undoubtedly be anxious to know if the separation was final. I am happy to inform them that it was not; as we find the Princess of Penacook enjoying the luxuries of the shores and the sea breezes at Lynn, the next summer. How they met without compromising the dignity of the proud sagamore, history does not inform us; but probably, as ladies are fertile in expedients, she met him half way. In 1631 she was taken prisoner by the Taratines, as will hereafter be related. Montowampate died in 1633. Wenuchus returned to her father; and in 1686, we find mention made of her grand-daughter Pahpocksit.” Parts of the historical record of the English are very clear. According to the diary of John Winthrop, Montowampate and “almost all of his people” died of smallpox in September 1633. Below: Montowampate on the seal of the Town of Saugus, Massachusetts However, other historians have Wenunchus married to the younger brother of Montowampate, named Wenepoykin, a.k.a. Winnepurkett, called Sagamore George, who lived for many years, dying in 1684. Yet, even though he outlived his brother by half a century, his life was probably even more tragic. He was sold by the Puritans into slavery in Barbados in 1676 after being deemed a belligerent in King Phillips War...only to miraculously return like some lost prophet. After his return, he retired to Wamesit, the Praying Town for settled Indians, where he lived out his days, dying in 1684. As the recognized leader of the Saugus Indians and thus owner of the land from Salem to Saugus, immediately after his death the townspeople of Marblehead descended upon his “heirs”, including his elderly wife (not Wenunchus), obtaining a deed for their town on September 14, 1684. The deed was signed by Ahawayet, and many others, her relatives. She is called "Joane Ahawayet, Squawe, relict, widow of George Saggamore, alias Wenepawweekin." (Essex Reg. Deeds, 11, 132.) I suppose you can still go down to the land records office in Salem and look at her signature! The townspeople of Lynn and Salem soon followed suit, obtaining deeds from the heirs of Wenepoykin on September 4, 1686 an October 11, 1686 respectively. (Source: History of Essex County Massachusetts, 1888, by Duane Hamilton Hurd) But what if Wenunchus married Wenepoykin, not Montowampate, but also didn’t survive the shuttling between husband and father? This is the narrative tack taken, with some apparent poetic license, by one of the most famous poets of the mid-nineteenth century, and certainly the most famous poet until Robert Frost to be claimed by the lower Merrimack Valley region. (Robert Frost being claimed, rather surprisingly, by Lawrence because he graduated from Lawrence High School.) I am talking about John Greenleaf Whittier. The Story of Wenunchus in the Hands of John Greenleaf Whittier John Greenleaf Whitter was born on an ancient farm in Haverhill in 1807. It was built by his first Whittier ancestor in Haverhill almost a 150 years earlier. Although Whittier was self-educated, by the time he died in 1892, he was the author of one of the most famous poems of the day, Snowbound. This long piece, published in 1866, describes being stuck in the farmhouse on a snowy day, and it made him well-off financially. He ran in literary circles, mainly on account of being mentored in his younger days by an earlier publisher of his works, William Lloyd Garrison, in Garrison’s Newburyport newspaper. Garrison introduced him to the abolitionist cause, and to many literary lights of his day. Through these connections and the recognition he received for Snowbound, the self-educated Whittier received an honorary degree from Harvard in 1877. For his entire life, except for a spell of about three years working in New York and Philadelphia, he barely left the Haverhill-Amesbury-Newbury area. When Whittier did finally manage to see a bit of the world, it was mainly just places like the White Mountains and the Isles of Shoals. Whittier’s extreme provincialness, despite his involvement in the abolitionist movement and his honorary Harvard degree, is to me what gives his poems their authenticity. He is, to me, the voice of the historic lower Merrimack Valley. Snowbound is not just about being stuck indoors on a snowy day, it is about Haverhill and its history and setting. And one of his earlier epic tales, the Bridal of Pennacook, which tells the tale of Wenunchus and her marriage to [in Whittier’s version] Wenepoykin, whom he calls Winnepurkit, the poem is a vehicle for glorifying the entire Merrimack River, from the coastal sand dunes right up to the river’s highest headwaters. About his poem, “The Bridal of Pennacook” The poem was apparently written in 1844 but not included in any book of poetry for many decades. It is long – twenty five pages. It employs a conceit that the poem is composed spontaneously for entertainment by five hikers staying in a lodge near Mount Washington while the youngest of them recovers from her cold. The five characters who together compose the poem for their entertainment are the narrator, a writer and a poet; a city lawyer, “Briefless as yet, but with an eye to see /Life's sunniest side, and with a heart to take/Its chances all as godsends”; his brother a student training to be a minister, “as yet undimmed/By dust of theologic strife, or breath/Of sect”; a shrewd sagacious merchant, “To whom the soiled sheet found in Crawford's inn, /Giving the latest news of city stocks/And sales of cotton, had a deeper meaning/Than the great presence of the awful mountains/Glorified by the sunset”; and the merchant’s lovely young daughter, “A delicate flower on whom had blown too long/Those evil winds, which, sweeping from the ice/And winnowing the fogs of Labrador.” Whittier thus sets the scene: So, in that quiet inn Which looks from Conway on the mountains piled Heavily against the horizon of the north, Like summer thunder-clouds, we made our home And while the mist hung over dripping hills, And the cold wind-driven rain-drops all day long Beat their sad music upon roof and pane, We strove to cheer our gentle invalid After the lawyer tells her stories of his (mis)adventures fishing in the Saco River, and the divinity student, “forsaking his sermons”, recites poems to her from memory, the narrator rummages through the musty book collection at the inn, where he finds “an old chronicle of border wars and Indian history.” From this book the narrator reads aloud a summary of the story of Wenunchus and Montowampate, except in this version she is called Weetamoo (actually the name of a wife of a prominent native chief in Rhode Island) and, instead of marrying Montowampate, she marries that man’s brother Wenepoykin, whom he calls Winnepurkit. Our fair one [i.e. the girl], in the playful exercise Of her prerogative,—the right divine Of youth and beauty,—bade us versify The legend, and with ready pencil sketched Its plan and outlines… The self-taught Whittier tries to show his knowledge of classical Greek poetical forms, which I suppose was de rigeur for professional poets of the era. He does not say which character “versifies” which part of the Wenunchus story, but it might be possible to hazard a guess based on their supposed personalities. In the first section, the poem sets the scene, describing the pre-contact Merrimack River itself, “ere [before] the sound of an axe in the forest had rung, Or the mower his scythe in the meadows had swung.” This section is in so-called Alexandrine meter, twelve syllables per line with a stress on the sixth and last, in simple A-A B-B rhyme. Among other things, it takes the listener through the geographic features of the river: “Amoskeag's fall”, the “twin Uncanoonucs” stately and tall, the Nashua meadows green and unshorn, etc., all before “the dull jar of the loom and the wheel,/The gliding of shuttles, the ringing of steel” had invaded the river in the form of mills and waterworks. In the next section, the poem describes the stern character of The Bashaba, i.e. the great chief Passaconaway, in a more complex format: paired quatrains, rhyming aaab cccb, with 7-7-7-5 syllables, while the first stanzas are longer, nine lines for the first, ababbaddd. The character telling this section – the lawyer, perhaps? – weaves a tale of the awe inspired by Passaconaway: Here the mighty Bashaba Held his long-unquestioned sway, From the White Hills, far away, To the great sea's sounding shore; Chief of chiefs, his regal word All the river Sachems heard, At his call the war-dance stirred, Or was still once more. In the third section, the poem describes The Daughter, Weetamoo. The description focuses on her mother’s death giving birth to her (a detail certainly conjured up with poetic license), and the joy she ultimately brings to her stern old father, who decides not to take another wife. The meter and rhyme for this section is rather simple, likely the work of the merchant character; for the rest of this blog piece I’ll refrain from detailing the rhyming scheme of each section. The fourth section describes The Wedding itself: The trapper that night on Turee's brook, And the weary fisher on Contoocook, Saw over the marshes, and through the pine, And down on the river, the dance-lights shine. For the Saugus Sachem had come to woo The Bashaba's daughter Weetamoo, The fifth section describes Weetamoo’s New Home with her new husband, in the coastal marshes of Saugus far from her mountain homeland. Whoever tells this part of the tale is rather uncharitable about the coastal terrain of Essex County: A wild and broken landscape, spiked with firs, Roughening the bleak horizon's northern edge; And later, an equally dreary scene, it is contrasted with the mountain home of Weetamoo: And eastward cold, wide marshes stretched away, Dull, dreary flats without a bush or tree, O'er-crossed by icy creeks, where twice a day Gurgled the waters of the moon-struck sea; And faint with distance came the stifled roar, The melancholy lapse of waves on that low shore. No cheerful village with its mingling smokes, No laugh of children wrestling in the snow, No camp-fire blazing through the hillside oaks, No fishers kneeling on the ice below; Yet midst all desolate things of sound and view, Through the long winter moons smiled dark-eyed Weetamoo. There is an oblique reference to Weetamoo's sexual awakening as a wife ("o'er some granite wall/Soft vine-leaves open to the moistening dew"). However section ends with her husband sending her back home to assuage her homesickness, escorted by soldiers: Young children peering through the wigwam doors, Saw with delight, surrounded by her train Of painted Saugus braves, their Weetamoo again. The sixth section describes her time back at Pennacook, at first enjoyable but then fraught with anxiety when her husband does not summon her back: The long, bright days of summer swiftly passed, The dry leaves whirled in autumn's rising blast, And evening cloud and whitening sunrise rime Told of the coming of the winter-time. But vainly looked, the while, young Weetamoo, Down the dark river for her chief's canoe; No dusky messenger from Saugus brought The grateful tidings which the young wife sought. The clash of egos between her father and her husband overtakes the situation and she is forced to spend the winter up in Pennacook. The section ends with her fixing to leave as soon as the river thaws, by herself, down the Merrimack. The seventh section, the Departure, describes her planning then and her actual flight. The river is swollen with rain and snowmelt, full of iceflows. At first, she appears to be managing despite the danger: Down the vexed centre of that rushing tide, The thick huge ice-blocks threatening either side, The foam-white rocks of Amoskeag in view, With arrowy swiftness sped that light canoe. However, things start to go wrong: The small hand clenching on the useless oar, The bead-wrought blanket trailing o'er the water… It ends dramatically: Sick and aweary of her lonely life, Heedless of peril, the still faithful wife Had left her mother's grave, her father's door, To seek the wigwam of her chief once more. Down the white rapids like a sear leaf whirled, On the sharp rocks and piled-up ices hurled, Empty and broken, circled the canoe In the vexed pool below—but where was Weetamoo? The final section of the poem, the Song of Indian Women, is a coda of sorts, sang by “the Children of the Leaves beside the broad, dark river's coldly flowing tide.” The Dark eye has left us, The Spring-bird has flown; On the pathway of spirits She wanders alone. The song of the wood-dove has died on our shore Mat wonck kunna-monee! We hear it no more! You can read all of The Bridal of Pennacook by John Greenleaf Whittier online. The poem should be read out loud for its full impact. I tried to do just that. You can watch my efforts reading the entire poem (which takes about an hour) at these videos below. Someday I’d like to replace the awkward video images of my contorted mug reading, with a slide show of the New Hampshire landscape to accompany the poetry. Poetic license and appropriation of “other people’s stories” John Greenleaf Whittier applied poetic license to the story handed down by Morton and others. He embellished it and added details for dramatic effect. Should he be telling the story of Wenunchus at all? Current cultural sensitivities caution against “cultural appropriation.” Because Whittier was not a Pennacook Indian, should he be writing poetry about Pennecooks? How about the fact that he sets up the poem around discovery of “an old chronicle of border wars and Indian history”? Does this make the poem about something likely to be found in old New England of the 1840s, when the memory of French and Indian wars was fresher, and the sight of actual Native Americans along the Merrimack could still be something of living memory? And what if there are no Pennacooks left to tell the story? Can someone else tell the story? Should only native Americans tell the story? Some natives were enemies of the Pennacooks. For example, the Mohawks were fierce warriors who would raid Pennacook lands periodically from beyond the Hudson River and steal their grain stores. A huge battle between Mohawks and Pennacooks apparently occurred in 1615, when the Mohawks attacked Pennacook itself. Other tribes with which the Pennacooks sometimes battled included the Abenaki and the Taratines. I would argue that the inheritors of these tribes, some of which still exist, have no direct claim to the stories of the Pennacooks. Do the current inhabitants of the Merrimack Valley region have a right to appropriate the stories of the Pennacooks? It is probably true that the settlement by the English starting in 1620, and the diseases they brought, followed by war and appropriation of land, led to the extinction of the Pennacooks. Does that mean the descendants of actors in the 1600 and 1700s are barred from telling these stories? How about the fact that many “tribes” arrived in the Merrimack Valley only after the Pennacooks were long-extinct: the Irish, the Italians, the French-Canadians, the Dominicans, the Puerto Ricans…do they have less or more of a right to tell these stories about the history of their present-day land? My own belief is that artists can interpret any story, and whether it is offensive or not depends on specific presentation. It is never categorical based on some construct of the artists “tribe” versus that of his subject matter. The poetry of John Greenleaf Whittier is largely forgotten, even among people who read poetry. A lot of it is sentimental and cliched, and comes across as long-winded and maudlin to me. But within his oeuvre, there are nuggets everywhere about the Merrimack Valley and his home. People can get reacquainted with the old stories of their home, simply by reading his works. The Bridal of Pennacook is one story that is worth retelling. Maybe someday it will be turned into a musical?

2 Comments

John Eliot, pastor at Roxbury in puritan Massachusetts Bay Colony, developed an interest in saving native souls, apparently on account of his language skills. So in 1649 he petitioned Parliament back in England for support in the conversion of the Indians of New England. Parliament duly funded the Corporation for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England, with Eliot as its head.

The chief results of this enterprise were (1) production of an Algonquin language bible, which also required teaching hundreds of natives how to read; and (2) the formation of so-called Praying Towns, where Christianized Indians were supposed to settle. By 1674, on the eve of King Philips War, the first major conflict between natives and English colonists, the population of Eliot's praying towns numbered 4,000 Indians, according to Major Daniel Gookin, the first and only commissioner of Indian matters in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Native responses to Christianity varied widely. Some were hostile. For example, when Metacom, also known as Philip, the leader of the rebellion called King Philip's War, was preached to by Reverend Eliot, Metacom was disrespectful. He supposedly took hold of a button on Eliot's coat and said "I care no more for your religion than I do for this button" and yanked it off. Other natives stayed ambivalent, while yet other Indians instead were persuaded by Catholic missionaries coming down from New France of the superiority of Catholicism. Passaconnaway, the great chief of the Pennacooks, politely listened to Eliot's preaching as far up the Merrimack River as Amoskeag, present day Manchester, New Hampshire. His son Wonalancet, however, dutifully accepted Christianity fully. In May 1674, Wonalancet informed Reverend Eliot and his cohort of ministers: "Sirs, you have been pleased, for years past, in your abundant love, to apply yourselves particularly unto me and my people, to exhort, press, and persuade us to pray to God; I am very thankful to you for your pains. I must acknowledge I have all my days been used to pass in an old canoe, and now you exhort me to leave and change my old canoe and embark in a new one, to which I have been unwilling; but now I yield myself to your advice and enter into a new canoe and do engage to pray to God hereafter." At this time, Wonalancet and his followers apparently settled in Wamesit, present day Tewksbury although then called East Chemsford, which comprised 2,500 acres along the Merrimack River near its confluence with the Concord River. They picked a bad time to "enter a new canoe", however, because war was brewing. King Philip's War broke out in 1675. The Pennacooks strove to remain neutral, but even their Christianized members, known as "Praying Indians", came under English scrutiny. They fled north into the wilderness, only to be accused of treachery for running away. So they came back, although Wonalancet stayed up in the mountains. During their absence, they were ministered to by one of Eliot's assistants, Symon Beckham. When questioned by colonial authorities what they did out there in the woods, Beckham replied that "We kept three Sabbaths in the woods." "The first Sabbath," Beckham said, "I read and taught the people out of Psalm 35; the second Sabbath from Psalm 46; and the third Sabbath, out of Psalm 118." Beckham's listeners, all being versed in the Bible, no doubt understood the intimations of this Christian friend of the natives. Psalm 35 begins "Plead my cause, O Lord, with them that strive with me: fight against them that fight against me./Take hold of shield and buckler, and stand up for mine help." Psalm 46 begins "God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble/Therefore will not we fear, though the earth be removed, and though the mountains be carried into the midst of the sea." And Psalm 118 starts "O give thanks unto the Lord; for he is good: because his mercy endureth for ever./Let Israel now say, that his mercy endureth for ever." (All quotes are the King James version, which would have been used by the Puritans.) According to Major Gookin, on whose book this account is based, such Bible verses "were very suitable to encourage and support [the Wamesits] in their sad condition; this shows, that those poor people have some little knowledge of, and affection to the word of God, and have some little ability (through grace) to apply such meet portions thereof, as are pertinent to their necessities." Alas, being preached to did not help them. The natives were immediately blamed for burning down a barn in Chelmsford. Upon their return to Wamesit, this led to a skirmish with Chelmsford settlers, who killed a native boy and wounded five natives. Thereupon they wrote a pitiful letter to the government of Massachusetts: "The reason we went away from the English, for when there was any harm done in Chlemsford, they laid it to us and said we did it, but we know ourselves we never did harm the English, but go away peaceably and quietly. [As for the land reserved for our use], "we say there is no safety for us[,] for many English be not good, and maybe they come and kill us, as in the other case. We are not sorry for what we leave behind, but are sorry the English have driven us from our praying to God and from our teacher, Mr. Eliot. We did begin to understand a little [about] praying to God." No help came, so they left for the Pennacook headquarters, in present-day Concord, N.H. "On [Thursday,] February 6, 1676, having taken to the woods in search of Wonalancet, having lost their way and many lives by hardship and starvation." Even their retreat did not help. "[T]he English marched on Pennacook (Concord, NH). Wonalancet learned of their approach and led his followers into the swamps and marshes, where, from behind trees, they could watch every move of the whites. The soldiers destroyed their wigwams and winter's supply of dried fish. Wonalancet did not check the march of his refugees until the headwaters of the Connecticut River had been gained. Then only did they settle down, far from English wrong-doers, yet ever facing death, for the winter was a terrible one." (Charles Edward Beales, Jr. (pseud.), "Passaconaway in the White Mountains", 1916) In September 1676, the band of Wonalancet's followers were lured into a peace treaty with the English representative, Captain Richard Waldron, at modern day Dover, New Hampshire. The upshot of Captain Waldron's deception, which will be covered in another blog entry, was that over four hundred Pennacooks were captured there and then were sold into slavery in Barbados to help cover English expenses for the war. According to the Beales book, here is how Wonalancet then lived out his days: "Many tribesmen now abandoned the unresisting Wonalancet and went to the French at St. Francis [the present-day Abenaki reservation Odanack, Quebec]. By order of the Court, the decimated Pennacooks were transferred to Wickasaukee and Chelmsford, where they were under the supervision of Mr. Jonathan Tyng of Dunstable. Of the later years of Wonalancet's life little is known, until 1685, when, upon report of his 'fierce and warlike' presence at Pennacook, [this being his nephew Kancamagus leading the Androscoggins in revenge against Captain Waldron], he came to Dover, where he assured the government of New Hampshire (which now had become a Royal Province) that there were at Pennacook only twenty-four Indians beside squaws and papooses, and that this paltry band had no intention of making war upon the English. His name is not affixed to the treaty of this year, which seems to prove that he was no longer the recognized leader. Four years later, in 1689, he repeated his assurances of peaceful intentions. He is said to have again returned to St. Francis shortly after. Nine years later, he was again living under the care of Mr. Tyng, this time at Wamesit. The old sachem is reported as having transferred his lands, the last of his once vast domain, to his keeper. Deeds bearing dates of 1696 and 1697 are found, made out to Mr. Tyng. Whether he went back to St. Francis or died in his own country is not definitely known; the time of his death also is unknown. He is believed to have been buried in the private cemetery of the Tyng family, in Tyngsboro, Mass." Below is a summary of the Praying Towns closest to Boston (for Pennacooks and affiliated bands), followed by a summary of the Praying Towns in Worcester County (where the tribe was the Nipmucks).

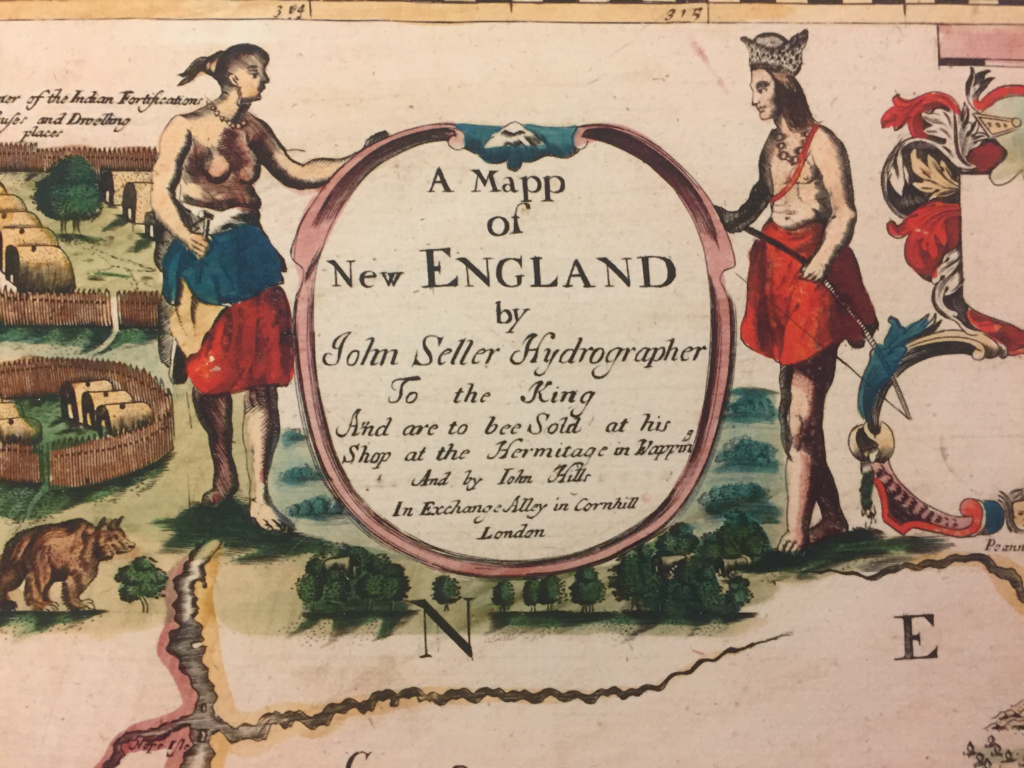

It is from “Biography and History of the Indians of North America: From Its First Discovery” by Samuel Gardner Drake (1848). The reference to Gookin was to Major-General Daniel Gookin, Commissioner of Praying Towns from the 1650s through the 1670s. “Natick, the oldest praying town, contained, in 1674, 29 families, in which perhaps were about 145 persons. The name Natick signified a place of hills. Waban was the chief man here, "who,"says Mr. Gookin, "is now about 70 years of age. He is a person of great prudence and piety : I do not know any Indian that excels him." Pakemitt, or Punkapaog ("which takes its name from a spring, that riseth out of red earth,") is the next town in order, and contained 12 families, or about 60 persons. It was 14 miles south of Boston, and is now Included in Stoughton. The Indians here removed from the Neponset. Hassanamesit is the third town, and is now included in Grafton, and contained, like the second,60 souls. Okommakamesit, now in Marlboro, contained about 50 people, and was the fourth town. Wamesit, since included in Tewksbury, the fifth town, was upon a neck of land in Merrimack River, and contained about 75 souls, of five to a family. Nashobah, now Littleton, was the sixth, and contained but about 50 inhabitants. Magunkaquog, now Hopkinton, signified a place of great trees. Here were about 55 persons, and this was the seventh town. There were, besides these, seven other towns, which were called the new praying towns. These were among the Nipmucks. The first was Manchage, since Oxford, and contained about 60 inhabitants. The second was about six miles from the first, and its name was Chabanaktongkomun, since Dudley, and contained about 45 persons. The third was Maanexit, in the north-east part of Woodstock, and contained about 100 souls. The fourth was Quantisset, also in Woodstock, and containing 100 persons likewise. Wabquissit, the fifth town, also in Woodstock, (but now included in Connecticut,) contained 150 souls. Packachoog, a sixth town, partly in Worcester and partly in Ward, also contained 100 people. Weshakim, or Nashaway, a seventh, contained about 75 persons. Waeuntug was also a praying town, included now by Uxbridge; but the number of people there ill not set down by Mr. Gookin, our chief author.” The Praying Towns were largely abandoned following King Phillips War, 1675-78, the first large-scale violence between English settlers and natives. Growing up I went to Littleton a lot, as well as Tewksbury. Never heard of Praying Towns even though the little ski area in Littleton, Nashoba Valley, bears the name of one of them. Below is a closeup of the Merrimack Valley section of an amazing map printed in London in 1670. Two cool features: First, it shows “Old Norfolk” County, the old county of Norfolk that extended from the Merrimack River north to the Piscataqua River. It existed from around 1640 to around 1680. Of note, Haverhill and Salisbury, being north of the Merrimack, are in Old Norfolk not Essex County where they later ended up, and so is all of what is now coastal New Hampshire. New Hampshire as a concept didn’t exist yet and Massachusetts Bay Colony asserted jurisdiction. Second, the map shows the Indian “praying town” of Wamesit, in modern-day East Chelmsford. The puritans (naturally) attempted to Christianize the natives. They - led by reverend John Eliot -went through great effort to translate the native Algonquin language into English so they could provide the Indians with a bible, called Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God. They also had to teach the natives to read this new book written in Algonquin, a hitherto oral language. The Algonquin bible is a fascinating topic to which I hope to dedicate future blog entries. I can't decide whether to take it seriously. Some of the translations in generated are so absurd on their face as to call into question the validity of the whole endeavor. For example, Elliot translated "our lusts" (an important word no doubt for the puritans as "Nummatchekodtantamooongannunonash" which cannot possibly be a word. He translated "our loves" as Noowomantammoonkanunonnash, and "our questions" as Kummogokdonattoottammooctiteaongannunnonash, which might be the longest word I have ever seen. Some of the natives who converted were settled in so-called Praying Towns. I will write a separate blog post on the Praying Towns. After the first war between the English colonists and the natives in 1675 (which basically launched fifty years of intermittent Indian attacks on settlements like Haverhill and Andover), the Praying Towns were abandoned. Also a topic for a future blog post. The towns of Andover and Haverhill are visible, along with places like Salisbury downriver and Chemsford upriver. Present-day Lowell is called Pawtucket and present-day Newburyport is called Agawamin (not to be confused with present-day Agawam in Worcester County).

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed