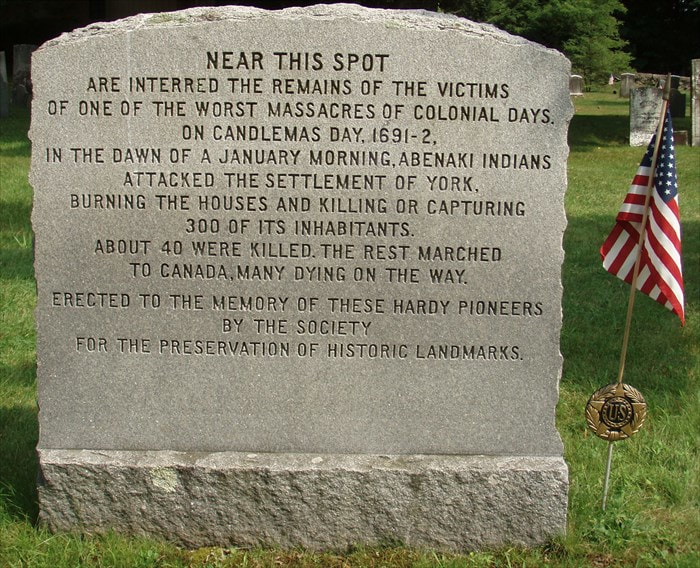

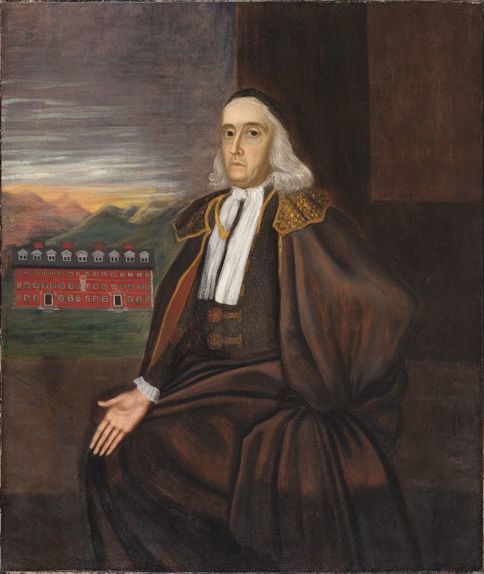

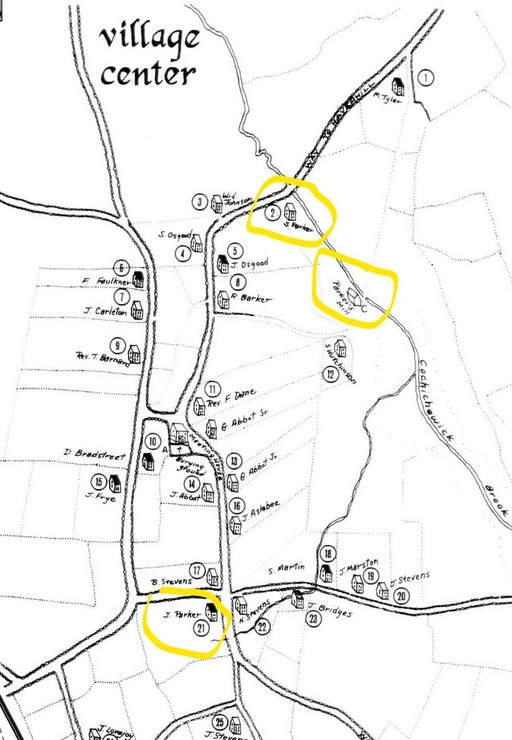

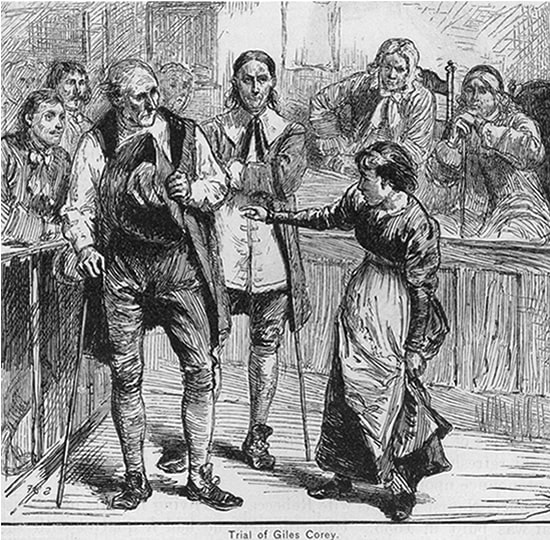

(A long read)Above: Monument to Mary Ayer Parker, Salem, Mass. Source: Find-A-Grave Background By the end of 1678, the first major episode of violence between natives and English colonists was over. Nearly 10% of the English population was killed in this King Philips War, but it was even more destructive for the natives. The eradication of the Narragansett and Wampanoag tribes and the weakening of the other tribes in the settled parts of New England did not mean the threat of Indian invasion disappeared, however. Instead, for the towns along the northwestern frontier of English settlement of North America – places like Haverhill and Andover – the threat actually grew. This is because the remaining natives became proxies in the rivalry between global empires, France and England. Some Indian groups had historically plundered the coastal tribes of New England...for example, the Mohawks from west of the Hudson, and the Ohio Valley-based Iroquois. Members of both tribes became paid mercenaries along the English-French frontier, in what is now Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont. Other tribes were fighting back against the encroaching devastation of their native lands. The Abenaki entered into a formal political alliance with the imperial government of France, seeking an established place in “Arcadia”, which was the colony of New France that extended from the present Canadian maritime provinces all the way down to the Kennebec River. Members of all three tribes became a threat to settlements of the puritan English frontier. Disruption to Lower Merrimack Valley and Northern Essex Region The first imperial proxy war became known as King William’s war, named after the distant English king, William of Orange, a newcomer from Holland who along with his wife Mary had inherited the English throne after the demise of the house of Stuart. He led a coalition of kingdoms against France. The opening volley in our part of the world was an attack directed by the governor of the Province of New England, who in 1688 organized a militia raid on the de facto French military leader of Arcadia, Jean-Vincent d'Abbadie de Saint-Castin, at what is now Castine, Maine, the southern-most point of French settlement. Saint-Castin was married to a Penobscot Indian princess and commanded mainly an army of Indians, aided by Jesuit priest-soldiers. This attack on Saint-Castine triggered war in the region. Abenakis and their French allies retaliated by targeting English settlements far down the Maine coast. They attacked Kennebunk in September of 1688; Salmon Falls (now Berwick) Maine in March 1690 (in which about 90 English villagers were killed or imprisoned for ransom); Wells in June 1691; and York in January 1692 (the so-called Candlemas Massacre in which 300 English villagers were killed or imprisoned for ransom). As a result of these devastating raids, dozens of English families fled southward into the relative safety of the Merrimack Valley and Essex County, past the warring tribulations of Kangamagus, last of the great Pennacook chiefs, near Dover. Below: Memorial to the victims of the Candelmas Massacre, January 24, 1692, York, Maine The refugees mainly swarmed Salem -- divided into Salem Town, now Salem, and Salem Village, now Danvers-- Ipswich, Haverhill and Andover. This influx of refugees strained resources and is thought to have contributed to the social unrest in these areas that caused “witch fever” to take hold. Although the hangings and other executions were centered in Salem Town, the most accusations of witchcraft apparently occurred in Andover, on the frontier twenty miles inland on the banks of the Merrimack. Andover had already suffered one Indian raid in August 1689, when the Peters house was burned and two persons were killed, so paranoia and apprehension likely ran high. Andover in the late Seventeenth Century The frontier region of northern Essex County in the late 1680s and early 1690s barely resembled the wilderness encountered fifty years earlier. Land had been allocated and cleared, and native trails became roads. Tight clusters of wood frame houses surrounded a parish meetinghouse; when the population grew too numerous, residents built houses far away from the meetinghouse. The road to Boston (present-day Route 28) and the road to Salem Town (present day Route 114) were bustling with trade at times, as grain, produce and timber made their way to market; and smoked fish, molasses from the rum trade, and finished goods made from England their way back to the hinterlands. Small boats could make their way up the Merrimack to Haverhill, site of the first falls, called Pentucket by the natives. Grist mills and lumber mills lined the streams, and tanneries and cottage industries provided basic clothing material, with the rest - such as cotton – shipped in through Boston and Newburyport. Despite the prosperity and relative stability of towns like Andover and Haverhill, the threat of Indian raids caused a general tone of apprehension. “The Indians were enemies very much dreaded. They concealed themselves and lay in ambush, and waited long and patiently, for an opportunity to surprise their prey. They never made their attacks openly, nor fought in the open field. The time of assault was often just before dawn of day, when they could strike the blow without resistance, and could cause the greatest panic. The inhabitants did not feel safe in their fields, and were liable to be shot down while at their labor. They frequently carried their firearms with them to their work. They also carried their guns when they assembled for worship on the Sabbath, and were exposed to be way laid in going and returning, and assaulted in the meeting house. They could not rest safely in their beds, without constant watch in time of war. They knew not when the enemy was near; they encamped in the wilderness, and were in the same place only a short time. It was as difficult to hunt them in the forest, as to hunt a wolf, and they were skillful at lying at ambush for their pursuers. Under such circumstances, the early settlers suffered exceedingly, not only from actual assaults, but from alarms and constant apprehension of danger. Their labors were often interrupted, much time was lost, and much expense incurred in securing their families and property. They were exposed, and suffered frequent losses, by destruction of their cattle, horses and barns, and pillage of their fields.” From The History of Andover, Mass. to 1829, by Ariel Abbot (1830). Thus there were grumblings about safety in the face of the obvious threat of Indian attack; however, nothing was done to form new parishes and build new meetinghouses and therefore form defensible new villages until a few decades later. Instead, newer residents lived far afield, in lone houses, on the edge of ancient forests that had yet to be cleared – rocky glacial soil made field clearance a slow and arduous task. Homes were timber frame, built using communal efforts, and covered either with clapboard, shingle or thatch-and-waddle. Some homes were built as “garrison houses” – brick in construction, with small windows that could be shuttered to keep out Indians and resist flame. One such house, the Peaslee Garrison House in East Haverhill, still stands today and was constructed around 1675 by my ninth great grandfather Joseph Peaslee [aka Peasley]. Above: Peasley Garrison House, East Haverhill, Built 1675 (now a private residence). Photo by the author. Similar garrison houses were erected on the periphery of Andover. Religious changes were evident too, causing further strain. The first two generations of New England puritans had been staunch believers, ready to sign up to covenants with their local puritan Meetinghouse vowing pure and virtuous life. Calling the churches “meetinghouses” signified the complete merger of religious life with civic life; all local governance took place within its walls. The right to vote in the local community was tied to membership in the church, which was limited to the elect who had undergone conversion by faith. But by the third generation, in the 1660s, there was a crisis. Were the grandchildren of the puritans who made the perilous journey to the new world presumed true believers? Or did they need to undergo their own personal “conversion”? A compromise was reached – they could sign up for a “half-way covenant”, in which, despite lacking a conversion experience, they could attend worship, but not receive rights to vote. This was the beginning of separation of local church and local government. By the 1690s, we were on the fourth generation, and church membership was plummeting… along with control of mores in the community, said the ministers. Yes, heresies in Boston had been dealt with, such as the expulsion of the Baptist Roger Williams to Providence plantation in 1636, the expulsion of Anne Hutchinson to New York in 1642 and the hanging of Quakers in Boston in the 1660s. However, apathy and alienation were harder to combat than zealous heresy. This was the context of the Salem witch trials. In addition to being the result of social strain wrought by King William’s War, the expansion of witch hysteria arguably represented an attempt by puritan leaders to use the situation to impose moral judgment. Sentences in the witch trials were handed down by William Stoughton, former puritan minister turned politician, who allowed most of the cases to be heard on the basis of spectral evidence: claims by witnesses of supernatural sensations. The court, after handing down its first execution in June 1692, adjourned to obtain advice of leading puritan ministers, who rallied behind the court’s purpose. The primary point of advice of the minsters was for the court to bring utmost help to those suffering molestations from the invisible world, by “speedy and vigorous prosecution of such as have rendered themselves obnoxious.” Below: William Stoughton, the Hanging Judge of the Salem Witch Trials, sitting in front of Harvard College, the seat of learning for the puritan ministry (Source: Wikipedia) Witches in the family John Ayer, the paterfamilias of all the Ayers in Haverhill and surrounding towns and my tenth great grandfather, passed from this mortal plane in 1657, in Haverhill. He left at least seven surviving children. His wife Hannah lived until 1688, dying at a ripe old age. By some accounts she was more than a hundred when she passed. John Ayer’s inventory upon death included “fower [four] cows, two steers, and a calf; twenty swine and fower pigs; fower oxen; one plough, two pair plough irons, one harrow, one yolke and chayne, and a rope cart; two howes, two axes, two shovels, one spade, two wedges, two betell rings, two sickels and a reap hook hangers in the chimneys, tongs and pot hooks; two pots, three kettles, one skillet, and frying pan in pewter; three flocks, beds, and bed clothes; twelve yards of cotton cloth, cotton wool, hemp and flax; two wheels, three chests, and a cupboard; ‘wooden stuff belonging to the house’; two muskets and ‘all that belong to them’; some books; some meat [presumably cured] about ‘fo[t]rie bushells of corne’; his wearing apparill; about six or seven acres of grain in and upon the ground; the dwelling house and barne and land broken and unbroken with all appurtenances forks, rakes, and other small implements about the house and barne.” Thus, he prospered in the new world. Their son Robert, my ninth great grandfather, was designated a freeman in 1666, made a selectman in 1685, and was known as sergeant of the local militia after 1692. He was even more prosperous than his father, whereas the refugees and other newcomers had virtually no possessions, eking out existences as boarders and field workers. Witchcraft came to the Ayer family when Robert’s sister, Mary Ayer Parker, of Andover, was accused of witchcraft in early September 1692, six months into the witch craze. She was hanged by the end of that month, proclaiming her innocence until her death. Mary had been married to Nathan Parker, a former indentured servant who had settled in Newbury with his brother Joseph sometime in the 1630s. By 1648, Nathan had bought his freedom and was living in Andover, as one of its first settlers. His first wife died, and within a few months he married Mary Ayer. The original size of Nathan Parker’s house lot was four acres but his landholdings improved significantly over the years to 213.5 acres. His brother Joseph, a founding member of the meetinghouse in Andover parish, possessed even more land than his brother, increasing his wealth as a tanner. By 1660, there were forty household lots in Andover (clustered around what is now North Andover common, the original village of Andover), and no more were created. Subsequent landholders built their homes far afield, near their farms. By 1650, Nathan began serving as a constable in Andover. Nathan and Mary had their first child, John, in 1653. Mary bore four more sons: James in 1655, Robert in 1665, Joseph in 1669 and Peter in 1676. She and Nathan also had four daughters: Mary, born in 1660 (or 1657), Hannah in 1659, Elizabeth in 1663, and Sara in 1670. Her son James died on June 29, 1677, age twenty-two. He was killed in a battle with Indians at Black Point, in what is now Scarborough, Maine, in one of the last skirmishes of King Philips War, along with his cousin John Parker (son of his father’s brother Joseph Parker), who had fought in the Great Swamp campaign in Rhode Island a few years previous. Nathan Parker, husband of Mary Ayer Parker, died in June 1685. He left an estate valued at 463 pounds – more than double the estate of his father-in-law John Ayer – and a third of it went to Mary his wife. It is not known what her lifestyle was like after 1685; however, she was likely living alone as all her children were grown and all the girls were married by this time and living in their own homes. Below: detail of map of Andover [now North Andover common] in 1692 prepared by the North Andover Historical Society. It's not clear which residence would have been Nathan Parker's. The accusation of witchcraft against Mary Parker She was accused by fourteen-year-old William Barker Jr. in his confession on September 1, 1692. Young William’s father, William Sr., and his thirteen-year-old cousin Mary Barker, daughter of the deacon of the Andover meetinghouse, had already been imprisoned for witchcraft three days earlier. The accused William Jr. stated that he had so recently converted to witchcraft that he “had only been in the snare of the Devil for six days.” He testified that "Goody Parker went with him last Night to Afflict Martha Sprague." Goody was an abbreviation of goodwife, a title used for most married women in puritan Massachusetts. Young William elaborated that Goody Parker "rode upon a pole & was baptized [by Satan] at Five Mile pond." [Now called Haggetts Pond] The examination of Mary Ayer Parker occurred the next day. At the examination, afflicted girls and young women from both Salem and Andover fell into fits when her name was spoken. These witnesses included Mary Warren (a twenty-year-old servant), Sarah Churchill (a refugee from Saco, Maine), Hannah Post (a twenty-six year old whose father Richard had been killed by Indians), Sara Bridges (Hannah Post’s seventeen year old stepsister), and Mercy Wardwell (age nineteen, already under arrest for witchcraft, daughter of wealthy Samuel Wardwell of Andover, who was eventually hanged for witchcraft the same day as Mary Parker). The records state that when Mary came before the justices, these girls and young women were cured of their fits by her touch, which was the satisfactory result of the commonly used "touch test," signifying a witch's guilt. Below: A witness performing the touch test on Giles Corey, accused of witchcraft Mary Ayer Parker was tried in Salem. During her examination she was asked, "How long have ye been in the snare of the devil?"

She responded, "I know nothing of it.“ Her defense was mistaken identity: other Mary Parkers lived in Andover – by whom she would have meant either her brother-in-law Joseph Parker’s wife Mary, nee Stevens, or their daughter. It was not clear why she would have tried to throw her relatives ‘under the bus’ (to use an anachronistic phrase). Perhaps there were still hard feelings over the death of her eldest son James after he followed their son John, his first cousin, into war against the Indians. In any case, the court did not buy her defense. Like most accused in the witch trials who protested their innocence rather than confessing being in league with the devil, she was found guilty and hanged. Conclusion Some people think the witch trials were purely the result of the belief systems of the Massachusetts puritans. However, they came into existence at a time of great social stress, as refugees fleeing horrifying Indian raids along the Maine frontier upset the social order of towns like Andover and Salem where they sought shelter. The belief system of the Puritan ministers became a weapon that could be used in a form of class warfare, in which the marginalized could bring down their superiors, especially ones haughty enough not to admit they were in fact witches.

4 Comments

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed