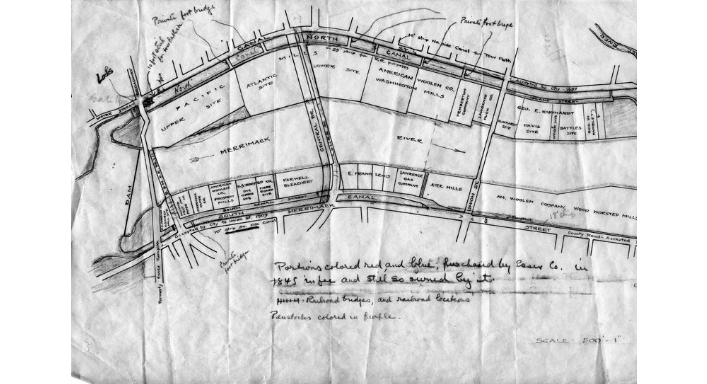

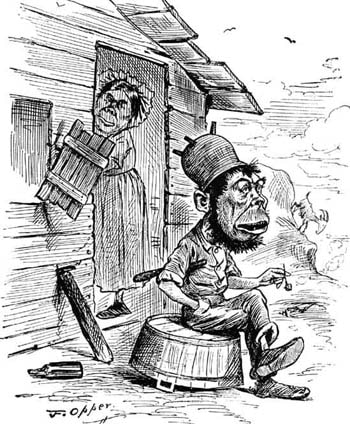

Above: Katherine O'Keefe O’Mahoney, born Ireland 1855, died Lawrence, Mass. 1918 (Source: Lawrence, Massachusetts by Ken Skulski, 1995) The Backstory Before there was Lawrence, there was ye olde New England: clapboard farmhouses, village greens, slow-moving farmers who mended their stone walls and carted their produce to market. This is how things were in 1845, the year Lawrence was founded as a town. Things in 1845 really weren’t all that different from 1645, two hundred years earlier, when the area was first settled by English Puritans in the towns of Andover and Haverhill. The ancient towns were later carved into the towns that we know today – Methuen, Salem N.H. (both formerly part of Haverhill), North Andover (the original part of Andover)…and Lawrence. Sure, the railroad had been introduced a decade earlier, and the Puritans had mellowed somewhat. People were no longer executed for witchcraft or whipped for heresy. But the culture was basically the same as it had been for generations. The original Puritan settlers had come forth and multiplied, cleared the land, built meetinghouses. Some of them went off to sea, chasing whale oil or Far-East silks and spices; or enterprisingly built waterwheels to grind their neighbors’ grain. Some of the local militia boys had gone off to the Battle of Bunker Hill and other early encounters of the Revolution. Basically, however, people farmed, traded, read their King James Bibles, attended meetinghouse, lived and died. Things were homogeneous and consistent, generation after generation. Below: Typical New England farm of the early 19th Century, similar to Bodwell's Farm in what became Lawrence (Source: New England Historical Society) Then, in the second half of the 1840s, two things happened: (1) industrialization and (2) a refugee crisis. Here Come the Factories The fast-moving tributaries of the Merrimack River had always powered waterwheels – little mills that were used to grind grain, saw logs into boards, or run a few looms to supplement the homespun cloth. However, in the 1840s, the mills being planned were different: they would now be on a grand scale. The immense new wealth of the spice trade and whaling was chasing new investments, and could finance endeavors on a previously unimaginable scale. The industrial revolution was underway in Britain and provided the technology. The planned textile city of Lowell was the first example, as we all know, but bigger and bigger factories could be planned. So a group of rich Boston merchant pooled their capital to form the Essex Company. In 1845 this company started to build Lawrence in a backcountry corner of Essex County, smack in the middle of farmers’ fields that had been cleared two centuries earlier. Their project – to build the largest dam in the world across the Merrimack and force its waters down two long canals to power dozens of enormous mills – required a lot of labor, the cheaper the better. Below: Plan for Lawrence showing new dam, canals and plots for water-powered textile mills, 1845 (Source Digital Public Library of America) Here Come the Irish Refugees And who should conveniently show up but a bunch of Irish refugees who could be put to work for pennies a day? These rag-clothed, impoverished, filthy bands of people were escaping the biggest humanitarian crisis of their time. The Irish Potato famine was so severe it killed one third of the people and forced another third to flee. The Famine Irish had arrived on dangerous, unseaworthy “coffin ships” operated by unscrupulous people-runners looking to exploit the desperation of the refugees. A risky voyage across the water was nevertheless preferable to staying in Ireland. Below: A So-Called Coffin Ship Leaving Queenstown (Now Cobh) Ireland, 1848 The Irish migrants crowded the port of Boston, then made their way inland, likely on foot, looking for work. The stream of refugees began in 1847 and did not abate until the mid-1850s. At Lawrence, they formed their refugee camp – the shantytown on the southern bank of the Merrimack – and the men started working on the dam. One of these laborers was my great great grandfather, Jeremiah Driscoll, arrived from Ireland in 1851 at age 29. He worked as a laborer for the Essex Company. His home address in the Lawrence town directory, once the town was big enough to have a directory, was “Shantytown, South Side.” Other Irish built a shantytown/refugee camp on the plains above Haverhill Street, near the Spicket River. A report from 1870 stated that some shanties had to be cleared for construction of the Lawrence reservoir. One of them was 120 feet long, and made of rough boards. It housed 80 people, mostly single men but also a family who built the place and charged the boarders a half penny a day to shelter there. Below: Derogatory Cartoon Depicting Shanty Irish Irish Pride in Early Lawrence Fast forward thirty-five years or so to 1882. Lawrence has grown from a couple hundred residents to 38,000…and around half of them are Irish. Although the town is seven square miles, most folks are concentrated in walking distance of the mills lining the river, spanned now by three bridges. There are by this time over a dozen large textile mills with more being built. The Irish, though largely still poor, have survived massive prejudice and exploitation within a largely hostile Yankee society. What do they do to show their pride? Do they march in a St. Patrick’s Day parade? Hardly – the first proper St. Patrick’s Day parade in Lawrence wasn’t until the 1900s. Go to a Riverdance concert? Listen to the Dropkick Murphy’s? No: they celebrated their Catholic faith by building magnificent churches and then organizing their lives around them. Below: Interior, St. Mary's Church, erected Lawrence, Mass. 1871

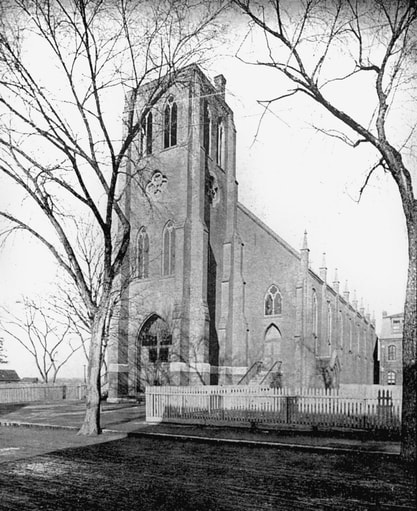

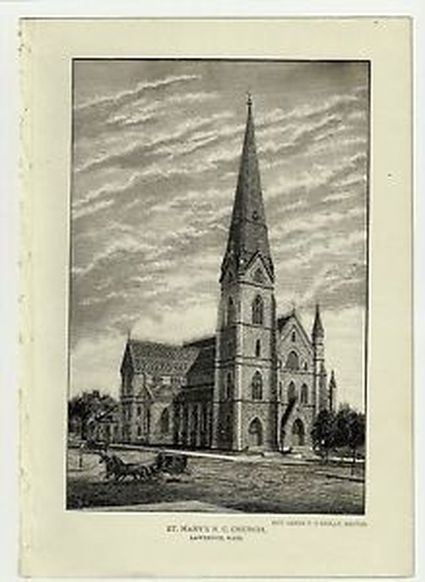

As one observer wrote, the Irish were known to spend their money on beautifying their houses of God before they beautified their own homes. Indeed, in 1882, three grand churches had been constructed of granite and brick in Lawrence – Immaculate Conception on Chestnut Street, St. Mary’s on Haverhill Street, and St. Lawrence O’Toole at the corner of Essex and Union Streets (it was renamed Holy Rosary in 1904 when the new St. Laurence O'Toole was built on East Haverhill Street). Yet at the same time, many Irish in Lawrence still lived in shanties. The last shanty was not torn down until 1894. Above: Immaculate Conception Church, Chestnut Street, Lawrence (Source: Queen City Blog). Lawrence's first permanent Catholic church, torn down 1991.The sense of Irish pride in their Church and its institutions – its grand churches, its rigorous schools, its charities like orphanages and hospitals – is captured in an 1882 book, “Catholicity in Lawrence” by Katherine O’Keefe O’Mahoney. According to Ken Skulski’s history of Lawrence, O'Keefe was “an author, lecturer and educator”. Irish-born, she graduated from Lawrence High School in 1873 (a rarity for girls, especially an immigrant girl), and then she started working there as a teacher. “Robert Frost considered her one of his favorite teachers. She was also among the first Irish-American women to lecture in New England. Her books include A Sketch of Catholicity in Lawrence and Vicinity (1882) and Famous Irishwomen (1907).” She also published a newspaper for Irish-American Catholics in Lawrence and conducted Irish classes there. She died at her Tower Hill home in 1918 at age sixty three. (Source: Ken Skulski’s Lawrence, Massachusetts.) For the about the first thirty year's of Lawrence's existence (until French Canadians started to arrive), pretty much the only Catholics in Lawrence were Irish. Reading O'Keefe's proud descriptions of St. Mary’s Church, you can get a sense of the importance of a magnificent church like this to the community:

Below: St. Mary's Church, Lawrence, Mass. erected 1871 For her, the priests are towering figures, and funerals of priests are the equivalent of a funeral for a head of state. The following is from her description of the 1875 funeral of Father Louis Edge, O.S.A., who built St. Mary’s along with the Augustinian Order. She claims that 10,000 people viewed his body lying in state in his coffin in front of the altar. Note the participation of the numerous Irish social and religious organizations: “Early on Monday morning, crowds began to assemble in the vicinity of the church, awaiting the opening of the doors. The Ancient Order of Hibernians, numbering nearly 150 men, were the first to enter, and to them was assigned the East wing; after them came the Ladies’ Sodality of St. Mary’s Church, with medals and white veils. They numbered over seven hundred, and presented a beautiful appearance. The Irish Benevolent Society, headed by the Lawrence Brass Band, were the next to enter the church. They numbered nearly two hundred, and bore a silken mourning banner; they were seated in the Gospel aisle. Next came the Ladies’ Sodality of the Church of the Immaculate Conception, in white veils, similar to St. Mary’s Sodality; they had been assigned to them the West wing. After them came the Men’s Sodality of St. Mary’s Church, wearing white sashes and white crosses; they were placed in the Epistle aisle. And then came the Catholic Friends’ Society, and the Conference of St. Vincent de Paul. The church was tastefully draped in mourning, the black festoons in the galleries were relieved with white rosettes, and the mourning on the altar with small white crosses. Over the altar was a large cross, formed of blazing gas-jets; and there was a star of gas-jets [!] in front of the organ. When the clergy, forty-six in number, entered the sanctuary to chant the Solemn Office, the scene was truly grand and impressive.” She then goes to name each of the forty six priests in attendance, treating each one as a celebrity. “The architect of this magnificent structure was [Irish-born] P. C. Keely of Brooklyn, N. Y.,” she continues. He was in fact one of the preeminent architects of Catholic churches in the Northeast in the latter half of the nineteenth century. “The stone work was under the supervision of James Trainor of Boston; the wood work was superintended by James Bulger of Burlington, Vt; and the painting, as we have recently stated, was by Schumacher of Portland, Me. Its cost was over $200,000.” Given that this amount was largely raised by small donations from the commuity, it is quite an amazing sum considering that a laborer made a couple dollars a week. Later, she describes the fundraising campaign to pay for the bells of the church (weighing a total of over 10,000 lbs). The list of donors reads like a directory of Irish residents of Lawrence: John Kiley, Sr., Patrick Moran, John Brennan, Patrick Connors, Joseph Morrissey, James Kilbride, Anne O’Donnell, Mary Anne Quinn, Mary Connolly, Mary Burke, Bridget Bradley, Catherine Cushing, Thomas Regan, Mary Dowd, Mary O’Brien, Mary McCarthy, Rose Walsh, Mary Burns, Sarah McGuohan, Maria O’Sullivan, Annie M. Rafferty, Kate Reilly, Ann Mahon, Mary McGuinness, Rosanna Mulligan, Ellen McCavitt, Hannah Moriarty, Mary J. Sweeney, Ellen Ryan… The list extends for a couple hundred more names, three quarters of them obviously Irish in origin. Far more than half of them are women. Katherine O'Keefe O'Mahoney dedicated her life to promoting Irish pride. I have newspaper clippings of a lecture tour she did in 1911, about Ireland featuring numerous illustrations. She is billed as "a little woman with an enormous voice." Irish Legacy In the Catholic Church By focusing on their religion as a defining institution of being Irish, the Irish came to dominate the Catholic Church in America. “In 1880, the percentages of the clergy who were Irish American was 69 percent in the Archdiocese of Boston…Moreover, in 1886 thirty-five (51%) of the sixty-eight Catholic bishops in America were Irish born or of Irish descent. In 1920, it was still the case that two-thirds of Catholic bishops were Irish American, and in New England, that proportion was three-fourths.” (Source: American Catholics in the Protestant Imagination: Rethinking the Academic Study of Religion, by Michael P. Carroll, 2010) Later, when other Catholic immigrant groups followed - first the French Canadians, then the Poles, Italians, Portuguese, Lithuanians and (a few) Catholic Germans -- they found waiting for them a church that could provide something of a welcome, whereas the Irish basically had to create the Church in New England. Epilogue Since the early 1990s, many of the grand Catholic churches of the original Catholic communities of New England have been closed and often torn down. In Lawrence, this includes the aforementioned Immaculate Conception and St. Lawrence O'Toole, as well as half a dozen other churches. The same pattern was repeated in other urban centers: Lowell, Haverhill, Fall River, Worcester, Boston. I hope this and other blog posts will remind people that these abandoned churches were not just religious institutions, but were part of the physical culture of the immigrant groups who built them. Below: Today's St. Mary's church (Santa Maria de la Asunción)(source: church website)

13 Comments

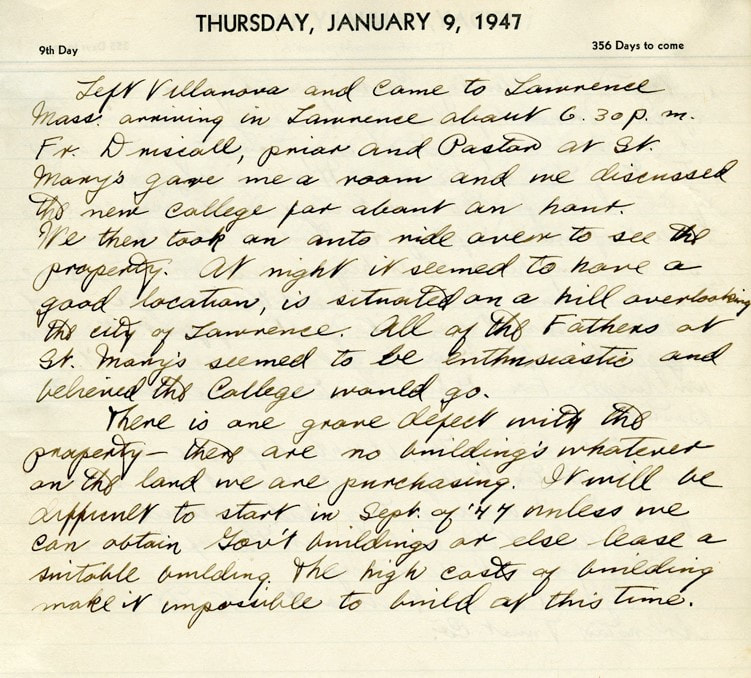

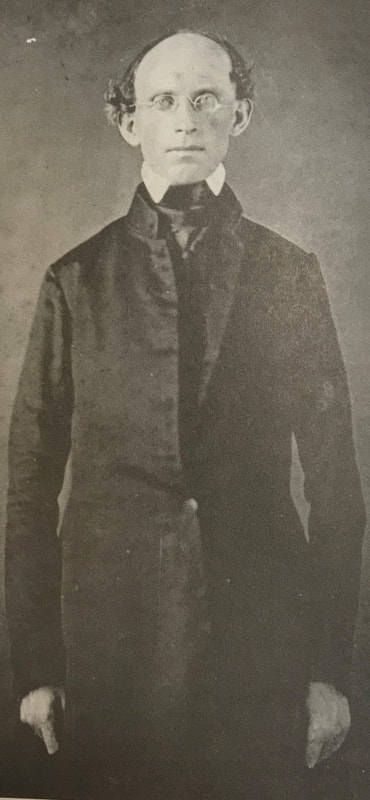

Above: My great-grandfather's nephew, the Rev. Daniel Webster Driscoll of Lawrence, circa 1950. Back in the day, every very good Irish family in America was supposed to have a cop, a lawyer and a priest. The priest in my maternal grandmother's family was her first cousin Father Dan, who also was an Augustinian friar. He likely became attracted to the Augustinian order because of their notable presence in his hometown of Lawrence, Mass. Like most Augustinians, his vocation took him through Villanova, and then to postings in various places where the Augustinians had missions at that time: the Philadelphia suburbs, then Carthage, in upstate New York, then Flint, Michigan. By 1940, he was back in Lawrence, serving as the head priest at St. Augustine's church in Lawrence. Later, he served at St. Mary's. Incidentally, he is mentioned in the documentary evidence relating to the founding of Merrimack College in North Andover in 1947. That effort was led by Father Vincent McQuade, a Lawrence native who was prominent in the Augustinian order. As a professor and Acting Dean at Villanova, he convinced the powers that be of the need to establish a second Augustinian college in the United States, after Villanova, in the Lawrence area. Father McQuade arrived in Lawrence on January 9, 1947 to take up his college-founding mission. Below is a copy from McQuade's journal from that day. Father Driscoll of St. Mary's, my relative, picked McQuade up at the train station in Lawrence and then drove him over to the planned site of the college in North Andover. It's nice to know my relative, albeit not ancestor, had a part in organizing this important institution for the region, Merrimack College. My mother's sister's husband, a returning G.I., was in the first graduating class. Father Dan also apparently acted as diplomat in family disputes; for example he seems to have had a hand in helping to negotiate the sale of some Driscoll land along Route 114 near Den Rock Park, where the shopping center now is. Below: Father James D. O'Donnell O.S.A., who brought the Augustinian order to Lawrence (O.S.A.= Order of St. Augustine) The story of the Augustinian "friars" in the vicinity of Lawrence, Mass. is one of the more unlikely happenings in our history. It is also a tale of a small number of dedicated men bringing great benefit to the area. Who are the Augustinians? Since the dark ages, the Catholic church has had monastic orders such as the Benedictines, in which dedicated priests and non-ordained members live a monastic existence, praying constantly to God and contemplating his wonders. In the 1200s, a different kind of order sprang up: mendicants, meaning they wandered instead of becoming hermits, and lived off local charity rather than estates. Like the monastic orders, they had priests as well as monks (essentially). The main mendicant orders are the Franciscans, named after Saint Francis of Assisi, and the Dominicans, named after Saint Dominic de Guzmán. Regardless of whether members are ordained priests or not, they are generally called friars. The Augustinian order was founded in 1256 by uniting four groups of hermits into a new order with a mendicant approach. It was never as prominent in size as some of the other orders, but nevertheless spread in missions to England, Ireland, the German speaking lands (Martin Luther was an Augustinian before he had his split with Catholicism) and elsewhere. The Augustinians come to America When Reverend Matthew Carr, a 41 year old Irishman, arrived in 1796 as the first Augustinian in America, “there was only one Catholic diocese in the whole immense territory, from Georgia to New Hampshire and from the Atlantic Coast to Mississippi." (quoting Ennis, No Easy Road: The Early Years of the Augustinians in the United States). Catholics at that time numbered about 35,000 in a total population of nearly four million. They were concentrated chiefly in Maryland and Pennsylvania (Baltimore was the sole diocese), but small groups of Catholics could be found elsewhere. Numbers of the Augustinian order in America increased slowly, to about 14 after a few decades. For the first forty years, all the Augustinians in America were Irish-born. Arthur Ennis, who wrote the preeminent early history of the order in America, surmises that their Irish background made them particularly suitable for lone efforts in their "mission":

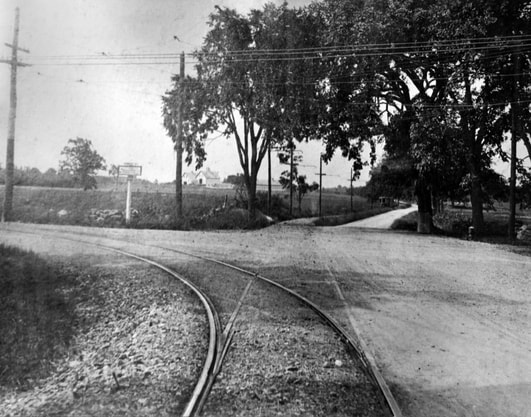

They launched their mission in Phiadelphia and built a church, St. Augustine's, that later was burned in 1844 by a nativist mob. They nevertheless persevered. They founded Villanova College around that time in a Philadelphia suburb. It would quickly become a seminary to train priests in the Augustinian tradition, and ultimately one of the more prominent Catholic universities in the United States. Below: Villanova College in 1849. Photo from Wikipedia. The Mission to Lawrence: Father James D. O'Donnell O.S.A. The Augustinian connection in Massachusetts came about through the work of James O’Donnell. The Irish-born immigrant was the first Augustinian priest ordained in the United States, in 1837, after entering as a novice in 1832 at St. Augustine's in Philadelphia. He was on the faculty of Villanova when the school opened in 1842. According to Ennis, how the Augustinian ended up in Lawrence is something of a mystery. “Father James had departed from Philadelphia early in 1848, apparently in a rebellious mood; his ambition went unsatisfied, he felt frustrated, bored with the small tasks assigned to him. He went off on a visit to Ireland, and before the end of the year he was back, hard at work now in Lawrence, assigned there by Bishop Fitzpatrick of Boston. How this came about is a puzzle. Although there is no record of permission given to him by his Augustinian superiors, he evidently received approval for his move to Lawrence, granted perhaps after the fact, for he would not otherwise have been acceptable in the diocese of Boston." Lawrence at that time had just been established and was a boomtown. Roads were being laid out, institutions were being constructed, such as libraries and schools, and mill buildings were going up everywhere. Catholic immigrants were pouring in. Destitute Irish laborers fleeing the potato famine had taken up vacant land just south of the river and soon had built over a hundred shanties. They were put to work, digging the canals and constructing the great stone dam, the largest dam in the world, that provided water power to the mills. According to a census taken in 1848, the town had a population of nearly 6,000, up from a couple dozen Yankee farmers two years earlier. Of that number, 2,139 were natives of Ireland, and presumably the vast majority of them were Catholic. Father James immediately embarked on a building spree to meet the needs of the burgeoning Catholic population. Although a small wooden church, Immaculate Conception, had been built in 1846 by a Father Charles Ffrench (not a typo), another mendicant friar (albeit a Dominican), Father James surmised the need for more houses of Catholic worship. He arrived in Fall of 1848 and promised that he would be saying Mass in a new church on New Year’s day. When the day came, the new church was barely walls and timbers, with snow falling through the open roof. However he said Mass as promised and a few months later the church was finished, being the first St. Mary’s. He financed the construction efforts with a church bank, taking deposits from his parishioners at interest. A few pennies a month from each of the couple thousand members added up, and lucky for him there were no bank runs (although in 1882 there was a run on St. Mary’s bank when a large number of depositors sought to withdraw their savings during a labor strike)(Source: Ennis). O'Donnell barely had time to rest before he set about building a larger church, this time of stone, on the same site. The construction took place all around the little wooden church, and then the new, larger church was completed, the wooden structure was torn down and its beams were used to construct a rectory for the priests. Then, in 1861, O'Donnell constructed a massive replacement church, also called St. Mary's, after buying up land on both sides of Haverhill Street. This structure, which burned down in 1967, became the St. Mary's school following the construction of the (still-standing) St. Mary's "cathedral" nearby on Haverhill Street in 1871. Below: Photo from the Lawrence Public Library archives of the original St. Mary’s granite building, which became the second St. Mary’s school. This building was destroyed by fire in 1967, after which time the high school became solely a girl's school. St. Mary’s High School for girls began instruction in 1880 and closed in 1996, when nearby Central Catholic high school began admitting girls. St. Mary’s Elementary School closed 2011. Source: Louise Sandberg, library archivist, on her Queen City blog. Father James also organized the parochial school system with the help of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur and began ministering to some of the nearby Catholic communities. He regularly visited Methuen and Ballardvale (the main mill section of Andover at that time). On November 22, 1853 he blessed the first Catholic chapel in Andover. This church, St. Augustine's, survives and prospers to this day under the auspices of the Augustinian order, in a later-constructed building. O'Donnell's strenuous activity must have taken a toll on his health, for he died quite unexpectedly on April 7, 1861, only days before his fifty-fifth birthday. No cause of death is recorded, but his illness was sudden and brief for on the previous Sunday he had presided at Easter services. The Augustinians in Lawrence after James O'Donnell's near one-man-show Following the untimely death of Father James, a series of prominent Augustinian priests ran things in Lawrence, although for most of the following decades they were only two or three on the ground. These included Rev. Ambrose McMullen, O.S.A. (in Lawrence 1861-1865), Rev. Thomas Galberry, O.S.A (in Lawrence 1867-1872 I believe), Rev. John Gilmore (in Lawrence 1872-1875). I say prominent mainly because they later went on to do great things, such as serve as president of Villanova (Mullen and Galberry), or become a bishop of the diocese of Hartford (Galberry). Mullen returned to the area after his tenure as college president, serving as pastor of St. Augustine's in Andover, where he died on July 7, 1876 at age 49. Photo below: Rev. Ambrose McMullen, O.S.A. Father Mullen was first stationed at St. Augustine's in Philadelphia and later in Lawrence, Massachusetts, where he continued the work of Father James O'Donnell. From 1865 to 1869, he was President of Villanova College. His next assignment was to St. Augustine's, Andover, Mass., until his death in 1876. He is buried in Saint Mary's Cemetery in Lawrence, Massachusetts. The construction of St. Mary's was followed by the organization of numerous churches in Lawrence in addition to that church and Immaculate Conception. Six other Catholic churches in north Lawrence were ultimately under the care of the Augustinians, many serving immigrant communities: St. Francis (Lithuanian Catholic) on Bradford Street, dedicated 1905 closed 2002; Sts. Peter and Paul (Portuguese Catholic) on Chestnut Street, dedicated 1907 closed 2004; Church of Assumption of Mary (German Catholic) on Lawrence Street (where I was baptized as an infant in 1971), dedicated 1897 and closed 1994; Holy Trinity (Polish Catholic) on Avon Street, dedicated 1905 closed 2004; St. Laurence-O'Toole, dedicated 1903 closed 1980; and St. Augustine's on Ames Street, where I went to Mass as a child, merged with St. Theresa's of Methuen, 2010, with masses celebrated once weekly in the St. Augustine's building, now called a chapel. Here is the Boston archdiocese list of merged or suppressed churches. My great-grandfather's nephew, Rev. Daniel Driscoll O.S.A. (1886-1963), was educated at Villanova and finished up his priestly vocation at St. Mary's in Lawrence. The 1940 federal census lists him living in the St. Augustine's rectory on Ames Street as the head priest along with two other priests; he later was at St. Mary's. Below: Photo of my great-grandfather's nephew, Father Daniel Webster Driscoll, O.S.A. (circa 1950?) of Lawrence, Mass. Served as priest at St. Augustine's, Lawrence, then St. Mary's. Founding of Merrimack College, North Andover, in 1947 Merrimack College was founded in 1947 by the Order of St. Augustine at the invitation of then Archbishop of Boston, Richard Cushing. It was founded to address the needs of returning G.I.s who had served during World War II, and is the only other Augustinian college in the U.S. besides Villanova. Rev. Vincent A McQuade, O.S.A., was a driving force behind the establishment of Merrimack and served as its first president. During his twenty two years in that position, he developed the college into a vital resource in the Merrimack Valley. "Vincent Augustine McQuade was born in Lawrence, Massachusetts on June 16, 1909, the son of Owen F. and Catherine McCarthy McQuade. The product of a Catholic home, Father McQuade was a son and a brother who attended St. Mary’s Grammar School, graduating in 1922. In August the same year, at age thirteen, he was received as a Novice in the Order of Saint Augustine. A graduate of Villanova University in Philadelphia, Father McQuade was ordained in 1934 and received his Master’s and Doctoral degrees from Catholic University in Washington, D.C. Father McQuade was a member of the faculty at Villanova from 1938 through 1946 who served in a succession of administrative roles including Acting Dean and Assistant to the President. Father McQuade also held a number of positions that required him to minister and advocate for servicemen, befitting the future founder of a college conceived in part for returning veterans." (source: https://merrimack.smugmug.com/History/The-College-on-the-Hill/) Below: Future site of Merrimack College, Wilson's Corner, North Andover, 1946. Source: same Today, Merrimack College has:

Photo below: Merrimack College, North Andover, "a selective, independent college in the Catholic, Augustinian tradition whose mission is to enlighten minds, engage hearts and empower lives". Source: college website. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed