|

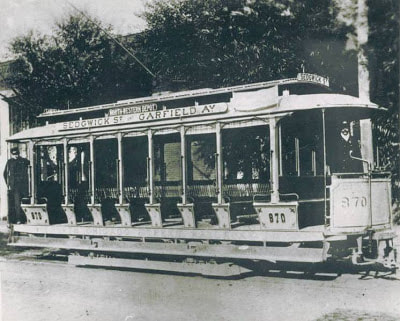

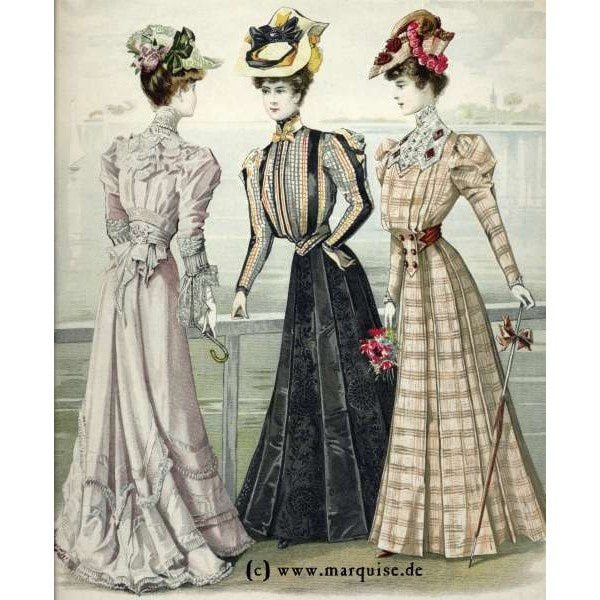

For many decades in Lawrence, from the 1920s through the 1960s, apparently nobody gave any historical significance to the 1912 strike, called the Bread and Roses Strike by some historians. However, by the time I was growing up in Lawrence in the 1970s and 1980s, and textile manufacturing was long dead and gone in the area, the following narrative became popular, not only to explain the strike but to explain the textile industry: Once upon a time, there were some greedy mill owners, who made a lot of profit by exploiting textile workers. The workers had a strike in 1912. They won. Wages increased, and inferior living standards were exposed, making living standards better for everyone. Everything was hunki-dori until after World War 2, when the greedy mill owners decided to move production to the American South where there were no unions. The mills disappeared. The end. A rousing story for sure. But I can't help but be a skeptic and a cynic. I investigated. I questioned the prevailing narrative. It turns out there are potentially a bazillion things wrong with this narrative. The problems have to do with all sorts of things: the misunderstanding of who the "mill owners" were (answer: blue-haired ladies on Beacon Hill with trust funds); the numerous strikes of the time, of which the 1912 Lawrence strike was but one (and a largely insignificant one except for its excellent immigrant participation); massive immigration from Southern Europe in the preceding fifteen years and the subsequent backlash that led to the closing of America's borders in 1920; etc. I'll save my numerous specific critiques of the Bread and Roses narrative for later blog posts. The key point I would like to make here is more basic: nobody these days who pays attention to the history of textile manufacturing in the Merrimack Valley seems to see the story right before their eyes. It is a story that explains the whole arc of the American Woolen Company, from its founding in 1899 to its ultimate demise in 1954. The lost story is this: the company basically only produced one thing, worsted woolen fabric. Miles and miles of it. Every year. For example, in 1912, the year of the strike, it produced 2 million square feet of worsted woolen cloth in Lawrence alone. And the company had production in numerous other New England cities. Fine. However, success does not come from production, it comes from sales. No matter how much production a company has, it is successful only if it can sell its goods. And who was buying most of the cloth by the early 1900s? Women. By the time the American Woolen Company was founded, the epicenter of fashion and clothing was the so-called Garment District of New York City, also known as the Fashion District, where fabric was turned into fashion. Textile companies lived and died by what they could sell there. From its inception, the American Woolen Company had its biggest sales office in New York City. In 1909, a few years after constructing the gigantic Wood Mill and Ayer Mill in Lawrence, the company constructed an impressive office in New York on the corner of Park Avenue South and 18th Street, dedicated to selling its product to the fashion houses and sweatshops of New York. Below: The American Woolen Company sales office near the Garment District, built 1909. At 19 stories, it would have been among the tallest buildings in New York at that time. Things were indeed hunki dori for a while. The strike occurred when confused immigrant workers spontaneously walked out on January 11, 1912 after their pay packets were short 3.57%. The pay was short, however, because the previous week they had worked 54 hours instead of 56 hours due to a progressive piece of Massachusetts legislation that reduced worker hours. At the end of the day, when the company acquiesced, the workers got a 15% raise and profits weren't affected. So good for them. The problem occurred later, in 1926, when fashion changed dramatically and demand for worsted wool plummeted for good. Rather than explain what happened in words, I'll illustrate: Before the decline of the Company: Women got around in this kind of transportation (a drafty open-air trolley): And they wore this kind of fashion: (warm woolen dresses that covered head to toe) Worsted wool cloth was essential. However, throughout the 1920s, the automobile was replacing the streetcar as the primary means of transportation. And automobiles had heaters, especially after the mid 1920s. Clothes could now be made of stylish light fabrics such as rayon, instead of stodgy worsted wool. So by 1926, women wore this kind of fashion instead (made of synthetics such as rayon): It would not be possible to wear such an outfit in a drafty open-air streetcar! Luckily, there was a new form of transportation, the motorcar. The automobile is ineffably linked to 1920s women's fashion, because it made the fashion possible. This is why when you see a photo of a woman in the late 1920s, wearing a skimpy synthetic dress, she is standing next to or riding in a car: without the car and its heater, she simply would not be able to get around dressed like this! Above: advertisement for aftermarket automobile heater, 1922. By 1929 with the advent of the Model A Ford, heaters were standard, along with that newfangled invention that changed mass culture, the radio. Below: typical flapper attire, made of synthetic fabrics. The monthly publication of the National Women's Trade Union League of America, an offshoot of the American Federation of Labor, noted in 1927: "Because the American woman isn't wearing those voluminous woolen garments any more, the woolen industry is suffering a hardship. An abnormally poor demand for woolen goods, coupled with a decline in raw wool prices, last year caused an operating loss of over two million dollars to the American Woolen Company, according to its 1926 annual report." In response to the massive changes in the textile market wrought by the motorcar, did the executives of the American Woolen Company respond by developing their own polyester and rayon production sites? No. Instead, they continued to produce miles and miles of worsted woolen cloth, even though demand (and prices) had dropped for good. A company can make a profit two ways: by making something that's better, newer fresher thus commanding a high profit; or making something that's cheaper, by squeezing production costs. After the loss of 1926, which put the American Woolen Company on the front of Time Magazine and arguably contributed to the suicide of William Wood, the founding president, the company henceforth pursued low costs rather than high value. Thus began the long slow demise of the American Woolen Company. It is no coincidence that the highpoint of Lawrence's population was the mid 1920s, when it was over 90,000. As jobs were reduced as a result of slowing production, workers moved away. The depression was a tough time, and the company was arguably only saved by the massive governmental orders from World War II and the Korean War for woolen cloth for military uniforms and blankets. However, demand had decreased so much and the prices for worsted wool had dropped so much, that if they wanted to stay in business at all making woolens instead of more exciting stuff, they had no choice but to chase low prouction costs for their low-value product. Hence the moves in the 1940s and 1950s to the South, followed by moves overseas. Imagine if the executives had innovated instead? However, that would have meant reinvesting the profits into new machinery, new technology, instead of paying high dividends every year on the preferred shares. Unfortunately innovation did not have the support of the trustees of the various Massachusetts trusts that owned the preferred shares on behalf of various old money families. Typically for such families, a great grandfather had originally locked up his capital - vast amounts of wealth made in the days of the clipper ship and the spice trade - into manufacturing companies that then got combined into the American Woolen Company. Rather than entrust his wealth directly to his heirs, who might squander it, it had been placed in trust. Boston is the original home of “asset management”, as it is called now, thanks to the widespread practice of locking family wealth into trusts where it would then be managed conservatively. The trustees did not see it as permissible to cut off the steady flow of dividends to their fiduciaries. (Which gets me to a tangent: in the 1970s, a small Lawrence-based textile manufacturer, Marlin Mills, that struggled on, did innovate, by inventing a warm, highly insulating, water-resistant cloth made out of recycled plastic fiber, called fleece. They marketed it under the brand Polartec, and it became the standard athletic wear used by high-end manufacturers of athletic clothing such as Patagonia, especially for cold-weather sports. Unfortunately, Marlin Mills did not bother to patent this great stuff they had invented so they could lock in long-term gain for their innovation. Instead, copycat fleece manufacturers quickly emerged, and the polartec cloth quickly became a commodity just like worsted wool had become a commodity. The company went bankrupt twice after trying to maintain production in Lawrence and now has moved production to Asia). So even if a company innovates to stay profitable, which is what the American Woolen Company should have done, it also has to take steps to protect its innovation, or it will suffer the fate of Polartec. PS: I didn't come up with this theory about the link between automobiles and their heaters, women's fashion, synthetic fabrics and the decline of the American Woolen Company. I got it from Frederick Zappalla, "A Financial History of the American Woolen Company," unpublished M.B.A. thesis, University of Pennsylvania, 1947. I have never seen this piece cited anywhere, so am not sure many other people have read it.

1 Comment

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed