|

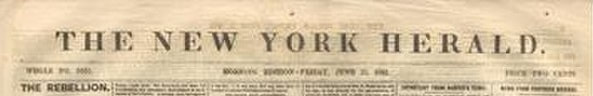

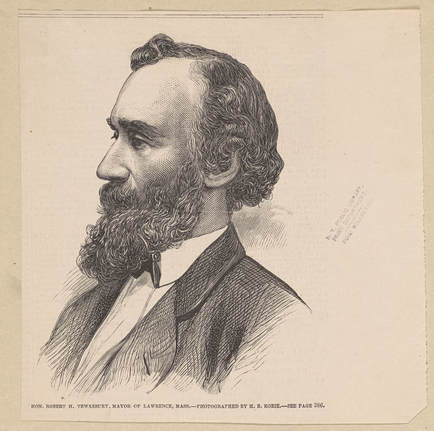

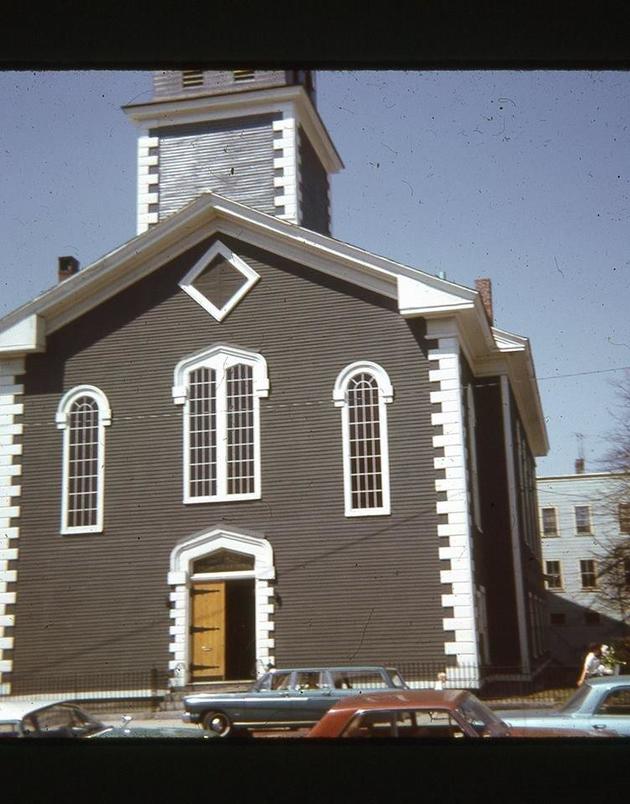

If you’re over forty, you probably remember bumper stickers like this all over Massachusetts: Among persons of Irish descent, support for the Irish Republican Army (IRA) was widespread, even if it was superficial. Somehow it was okay to like Princess Diana and Irish republicans… The IRA story was easy to understand. The British army was an occupying force. IRA men were freedom fighters, naturally fighting for a unified Ireland. British empire, bad. Freedom fighter, good. It’s all very romantic. Almost nobody from the area knows the story of the “other side”, the so-called Ulster Orangemen, who also made the region of Ulster their home. They were fighting for minority rights just as much as the IRA. Below: Logo of the Ulster Defence Association, paramilitary group The history of the Orangemen in a nutshell Ireland was ruled by the English crown starting in the 1500s. In the early 1600s, Scotland was technically still a separate kingdom. The English king had a problem. What to do with all those pesky Scots who lived on his side of the English-Scottish border? They kept trying to rise up against him. Solution: deport them to Ireland. These “Scots-Irish” (Americans like to say Scotch-Irish) were given land and rights in the province of Ulster, which was called a Plantation. They were supposed to raise sheep and pursue other productive ventures. Some of them soon left Ulster and settled the hillbilly regions of the United States. That’s another story. The ones who remained in Ulster had a tenuous relationship with the English powers. They refused to kowtow to the Anglicans who ran everything. Instead, they followed a very Calvinistic form of Presbyterianism. Although they had more rights and wealth than the Catholic population, they were an often-second-class minority within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Below: Political Cartoon from 1913 Regarding Ireland "Home Rule" When Ireland began to break away from Great Britain, the Ulster Scots leveraged their close-knit status as a political force. They won the separation of most but not all of the Ulster province from independent Ireland. The section in which they were a majority remained with Great Britain. The Ulster Scots saw themselves as a beleaguered minority of Ireland proudly clinging to their traditions. The British crown was now their protector, hence their extreme loyalism. The Orangemen One of the big traditions among Ulstermen is a commemoration of the Battle of the Boyne (July 12, 1690). In this battle, Protestant William of Orange, who rule as co-regent with his wife Mary II (hence the reign of William & Mary), defeated the deposed King James II, thus thwarting James’ failed bid to restore Catholicism to Great Britain. To commemorate this victory, Orangemen hold marches. During the “Troubles” of Northern Ireland, from 1969-1998, often these marches were designed to provoke their Catholic rivals, just as republican (meaning pro-Republic of Ireland) countermarches were designed to provoke Ulster communities. Technically, the Orangemen are a fraternal organization, comprised mainly but not exclusively of Ulster Scots (some are descended from English settlers of Ulster). It was technically founded as a brotherhood for all Protestants, in 1795 in County Armagh in Ulster. Below: Typical procession of Orangemen in Northern Ireland, July 12, 2016. PHOTOGRAPH BY Michelle McCarron. What does any of this have to do with the Merrimack Valley?? On July 12, 1875, the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne, a group of self-styled Orangemen held a picnic on the banks of the Merrimack River in Methuen. When they returned to Lawrence by way of steamer to Water Street, they were met a mob of 200 Irish Catholics. A riot erupted, and police fired at the mob. Here is the coverage from the New York Daily Herald: “Lawrence, Mass. – A serious riot occurred in this city to-night, resulting from an outbreak made by a mob upon the members of a lodge of Orangemen returning from celebrating the ‘Battle of the Boyne’ at a picnic at Laurel Grove, four miles up the Merrimac River. Orangemen from Lowell, Woburn and other towns participated at the picnic, which passed off quietly, and no trouble was anticipated when they dispersed for their homes, though some threats had been made in the morning and some of the men carried firearms in consequence. MOBBING THE LADIES About a dozen Orangemen, with ladies and children, disembarked at eight P.M., at the steamer landing on Water street, and started to walk up town. A crowd of several hundred Irish were at the landing and followed them, shouting and jeering. When they arrived in front of the Pacific Mills, the crowd commenced throwing stones, one of the ladies being struck three times and badly hurt. All the party were more or less injured by missiles thrown at them during their half mile walk to the police station, whither they went for protection. Four of the men had on regalia, which particularly incensed the mob. One of the men was severely hurt about the head and had his sash torn from him THE MAYOR JEERED AT On their arrival at the police station word was sent to the Mayor [ed: Robert H. Tewksbury], who soon arrived at the scene and undertook to disperse the mob of men and boys, but without avail; the cries and jeers of the mob drowned his voice. The Mayor, with a squad of police [editorial note: who were probably mostly Irish Catholic!], then started to take the party through the crowd to their homes. SHOWERS OF STONES Essex Street, through which they had to pass, was at this time filled for half a mile with the mob. Showers of stones, bricks and other missiles was [sic] hurled at the party as soon as it appeared upon the street. With the exception of the Mayor every one of the party was hurt. Policeman Gummel was knocked down and badly hurt. James Sprinlow, who was endeavoring to protect his brother’s wife, was knocked down, received a terrible wound in the head from a brick. At the corner of Union and Spring streets the mob made a furious onslaught of the party, when nearly all the police and Orangemen were knocked down. The latter then, in self-defense, drew their revolvers and began firing on them on the mob, who were shouting ‘Kill the damned Orangemen.” THE WOUNDED The firing quickly dispersed the mob, who scattered in all directions. It is impossible to learn the accurate result of the shooting. So far as known no one was killed. Two men, one woman and a boy twelve years old, were wounded; none seriously. Of the Orangemen twelve were wounded by stones and bricks, some of them quite seriously, and four policemen were more or less hurt. COURAGE OF THE MAYOR The riot lasted two hours and a half, and extended over a route of a mile through the most thickly portion of the city. It is the most serious affair of the kind that has occurred since 1852 [sic? Is this right? I thought the anti-Irish riot was in 1854], and is condemned on every hand as most unprovoked. The courage of the Mayor undoubtedly saved many lives.” Below: Robert Haskell Tewksbury (1833-1910), Mayor of Lawrence in 1875 Mary O’Keefe, whom I have written about, condemned the riot. She specifically cited the efforts by Irish Catholic clergy to distance themselves from the events. “And now we come to an event which we are doubtful about mentioning in a sketch of Catholicity in Lawrence for testing as we do, that Catholicity had no share in it. We refer to the ‘Orange riot’ which took place on the 12th of July, 1875, the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne, and was, by an accident, very largely advertised all over the country, and, of course, ridiculously exaggerated. However, lest we should be understood as acknowledging, by our silence, the truth of these reports, we here insert a card signed by the Catholic clergy of Lawrence, and published, at the time, in all the local papers. It expresses not only their sentiments, but those of all others in the city deserving the name of Catholics. “We, the undersigned, Roman Catholic clergymen of Lawrence, desire to publicly make known our condemnation of the riotous proceedings of last Monday evening. We do not consider as Catholics, in the proper meaning of the term, those who participated in the disturbance of the public peace, and who, by their shameful conduct, sullied the fair fame of our city. We teach our people good will towards all men, and we strive, by precept and example, to impress upon them the importance of faithfully observing the laws. We trust that the few ruflians who, under the name of Catholicism versus Orangeism, have created such bad feeling and given rise to so much trouble, may be made to feel the enormity of their crime. – SIGNED W. H. Fitzpatrick, Pastor of the Immaculate Conception Church; J. H. Mulcahy, Asst. Pastor of the Immaculate Conception Church; Jno. P. Gilmore, D. D. Regan, J. A. Marsden, O. S. A., Pastors of St. Mary’s Analysis and Questions What I would like to know: were these marchers really Orangemen, meaning they were really of Ulster descent? I have never heard of any Scots-Irish living in Greater Lawrence. I asked the Lawrence History Center, who have a redoubtable collection of materials related to dozens of different immigrant groups to the area. They have nothing on Scots-Irish, Ulstermen, Orangemen or anything similar. (There was however a large Scot-Irish settlement in Londonderry, New Hampshire - however, this town is probably too far away to have been the source of these marching "Orangemen".) I can’t help but think the march was of anti-Catholic types, of which there were still many (soon I hope to write about the Catholic school controversy of 1888 of Haverhill). But more research is needed. If anyone’s ancestor was a member of the Grey Presbyterian church in Lawrence, it would be great if you could contact me about the origins of your ancestors. Below: First Presbyterian Church (The Grey Church), 315 Haverhill Street(?), Lawrence, Mass.

0 Comments

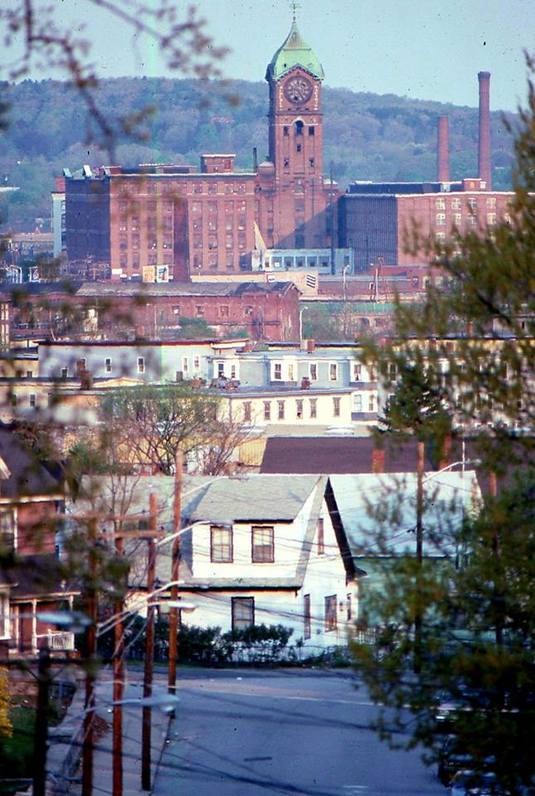

The Ayer Mill Clock Tower hovers above Lawrence, mid 1980s. Photo by Butch Fontaine.

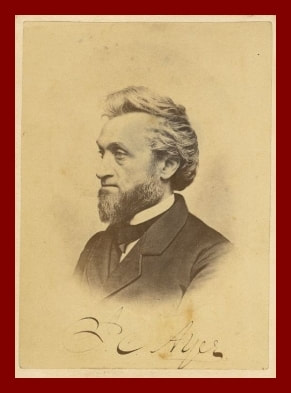

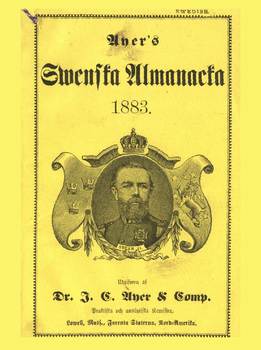

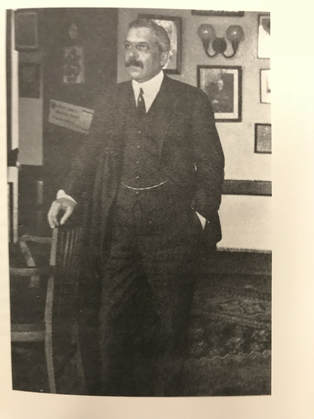

The Ayer Mill Clock Tower as a landmark There aren’t many landmarks left for a Lawrencian to point to. The beautiful post office? Demolished. The grand old police station? Demolished. “Theater Row” where many mill workers and their children watched the latest Hollywood talkies? Gone. Department store Sutherlands and the other large retail establishments of Essex Street? Gone. Also gone are many nice churches and schools, and even whole neighborhoods demolished for “urban renewal”. Most of the surviving Lawrence landmarks are industrial: the Great Stone Dam that made the whole place possible; and the mills lining the river and canals – the Pacific, the Wood, the Everett, etc. About half of the old mill buildings have been demolished. By far the most prominent landmark left in Lawrence is the clock tower of the Ayer Mill, now a New Balance factory. The tower rises 276 feet and is visible from many parts of the city, as well as from Interstate 495 passing by on the elevated roadway. It is the biggest mill clock tower in the world. As we all know, its clock face is only six inches smaller than the one on Big Ben. After decades of neglect the clocktower was restored in 1991 and has been maintained ever since. Below: Video of New Balance factory in Lawrence, Mass. This blog post tells the fascinating life story of its namesake, Frederick Ayer, peddler of patent medicines and almanacs who diversified into textiles. After you read it, maybe you’ll start calling the Ayer Mill clock tower “Big Fred”. Frederick’s background Practically every person in this country with the last name of Ayer – including my great grandmother Mildred Ayer – is descended from the original American Ayer [or Ayre or Ayres], named John. He was born in 1582 in Salisbury England and was a founder of Haverhill, where he died in 1657. John Ayer was Frederick Ayer’s fourth great grandfather, making Frederick a Haverhillite of sorts (and my sixth cousin five times removed). However, three generations earlier his family had moved from Haverhill to the coast of Connecticut. Frederick was born in Ledyard Connecticut, near New London, in 1822. Below: Frederick Ayer late in life. Source: Wikipedia His Brother James Cook Ayer and Ayer’s Patent Medicines For the early part of his life, Frederick followed in the shadow of his older brother, “Dr.” James Cook Ayer, born 1819. James studied medicine, apparently in Philadelphia, and may or may not have become a proper doctor. He did however become an extremely successful proprietor of patent medicines. James started practicing as a pharmacist in Lowell in 1841 at age twenty-three. His uncle lent him the money to buy his original pharmacy in Lowell. He settled there because his mother, a Cook, was from the Lowell area. He was a graduate of Westford Academy in neighboring Westford, Mass. Below: "Dr." James Cook Ayer, from his 1874 congressional campaign While a pharmacist James began developing cures for his customers’ ailments, and soon founded J.C. Ayer & Company. His five major products were Cherry Pectoral (“cure-all”), Cathartic Pills (laxative), Sarsaparilla (cure for syphilis and other “blood disorders”), Ague Cure (anti-malaria), and Hair Vigor (against thinning hair). Cherry Pectoral was by far his most popular and profitable product. Its popularity was possibly aided by three grams of opium in every bottle. In 1859, the company built a facility at 165 Market Street, Lowell, which they later expanded. By 1865, Ayer employed 150 people. In one year the factory processed 325,000 pounds of drugs, 220,000 gallons of spirits and 400,000 pounds of sugar. Below: Ayer's Cathartic Pills. Source: Cliff Hoyt website (http://cliffhoyt.com/jcayer.htm) Ayer’s Almanac James distinguished himself from other quacks – um, I mean doctors – by means of extensive advertising. In 1851, he hit upon the idea of providing a free almanac to all his customers. Almanacs were already essential household items, offering a range of helpful information for the current year – from public holidays to suggested planting times to town directories to historical summaries. However, James also peppered his almanac with advertisements for his products. Print production of Ayer’s Almanac is estimated to have exceeded 16,000,000 and was possibly as high as 25,000,000. The J.C. Ayer Company’s modest slogan for its publication was ‘Second only to the bible in circulation.' The almanac was eventually published in twenty-one different languages, reflecting the burgeoning immigrant population of the last decades of the nineteenth century. Below: Examples of foreign language copies of Ayer's Almanac (Source: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/almanac/heyday.html) James looked for a marketing opportunity wherever he could find it. For example, during the Civil War when Congress allowed postage stamps to become legal tender due to a shortage of currency, James encased stamps in miniature advertisements to protect them from wear and tear but also market his brand (source: www.cliffhoyt.com/encased_postage.htm). Below: Encased postage stamps bearing J.C. Ayer insignia (Source: Cliff Hoyt website http://cliffhoyt.com/encased_postage.htm)

Above: Advertisement for Ayer's Sarsparilla. Source: NIH website

Transition of The Medicine Business to Frederick; James’ Business and Political Pursuits; His Untimely Death In 1855, James offered his brother Frederick a partnership, and ceded day-to-day operations to his younger sibling. He started to become a man of wealth and leisure, traveling on extensive tours. In 1865, he purchased a statute on a trip to Germany and presented to the City of Lowell. This “Winged Victory” statue still stands today in Monument Square in front of Lowell City Hall. Below: Victory Statue, Monument Square, Lowell (Source: Wikipedia) By the 1850s, he was looking for investments for his enormous profits. However, he seems to have been the “dumb money” that came in late – in 1857, he lost $2 million dollars when the Bay State mills in newly founded Lawrence went bankrupt. That was an enormous sum of money in those days. Later, in his book Some of the Uses and Abuses in the Management of Our Manufacturing Corporations, he complained of the ways in which shareholders like him were denied a voice because entrenched management controlled the governance apparatus of corporations. Basically, he said, the insiders rigged shareholder elections. These days, someone like James C. Ayer is called an activist shareholder. In the book James launched an attack on the firm of A. & A. Lawrence, the powerful firm founded by brothers Abbot and Amos Lawrence, consummate Boston Brahmins and benefactors of great cultural institutions. (Lawrence, Mass. is named after Abbot Lawrence.) I take this as an indication that the Ayers were outsiders, not connected to the commercial elite of Boston, such as the Lawrences, with their ties to Harvard and Unitarianism (you know, “Cabots talking to Lowells and Lowells talking to God” and all that). This observation helps explain Frederick Ayer’s very unusual decision, in 1886, to allow the swarthy Portuguese immigrant’s son, William Wood (a.k.a. Guilherme Madeira), to run his textile empire and marry his daughter. More on that below.

Ayer, Massachusetts (formerly a section of Groton) was set off and named after James Ayer in 1871 when he paid for the new town’s city hall. He had dreams of becoming an important public figure. In 1874, he ran for Congress and was heavily defeated. He was so unpopular, the citizens of Ayer even burned him in effigy. This was apparently too much for his ego to handle. He went mad, spending a number of months at a private insane asylum in New Jersey. James died in 1878, leaving his brother Frederick to run the family business empire for another forty years until his death in 1918.

Below: The Town Seal of Ayer, Massachusetts, named after James Cook Ayer Frederick Ayer Takes Over In 1878, Frederick was fifty nine years old and a millionaire many times over thanks to the patent medicine business. However, by this time he had embarked on his second act: textile magnate. After a number of setbacks – and the loss of stupendous amounts of money as his family’s mills in Lawrence kept going bankrupt – he managed to get a handle on matters by hiring William Wood of Fall River to run the businesses. The relationship began in 1886 when Ayer met Wood while the latter was selling shares to a new mill he wanted to build in Fall River. Instead of investing in Wood’s mill, he hired Wood to help run Ayer’s mill in Lawrence, the Washington Mill. One thing led to another, and within a few years Wood was making $25,000 a year (up from his original pay of $204 a year) and he had married Frederick Ayer’s daughter. Below: Frederick's Son-in-Law, William Madison Wood, 1914 (Source: McClure's Magazine) As William Wood’s biographer wrote of the 1888 marriage between William Wood, age 30, and Ellen Wheaton Ayer, age 29:

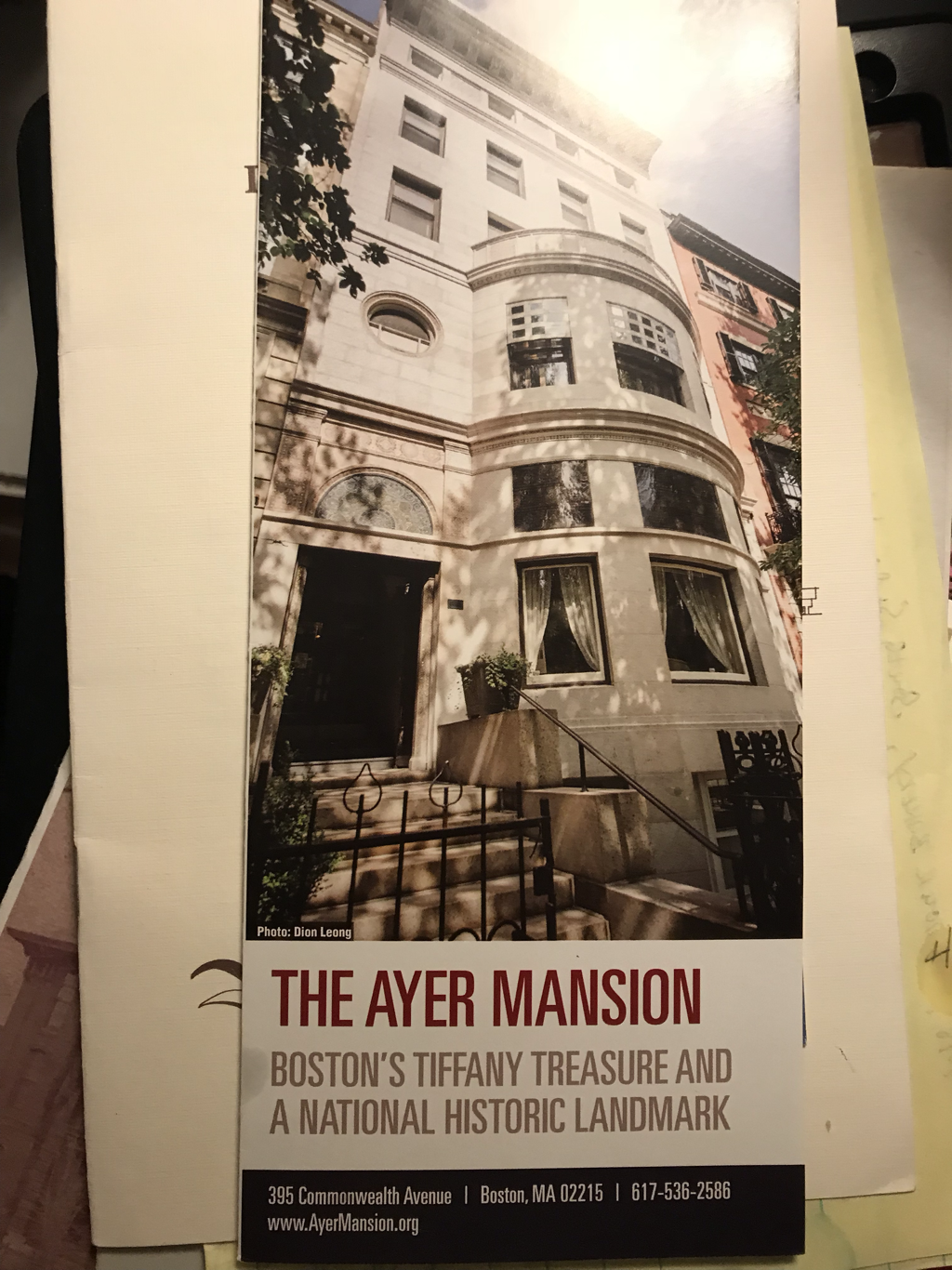

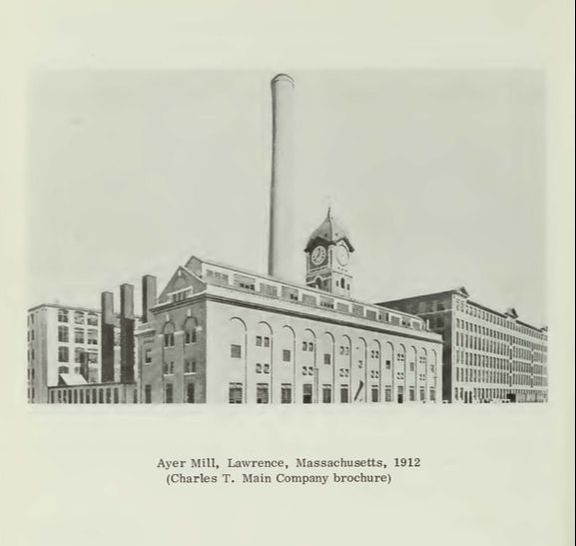

in addition to his involvement in patent medicines and textiles, Frederick Ayer was a founding director of the New England Telephone and Telegraph Company, serving in that role from 1877 to 1896. He was also a founding director of the Lowell & Andover Railroad, a subsidiary line of the Boston & Maine, serving from 1873 to the time of his death. (Source: his New York Times obituary, March 15, 1918.) Below: The Frederick Ayer Mansion, 357 Pawtucket Street, downtown Lowell (Wikipedia) Above: Brochure for the Ayer Mansion on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston Frederick Ayer was President of the American Woolen Company until June 1905, when he retired at the ripe old age of 83. Keep in mind that Ayer was still having children (with his second wife after the first one died) as late as 1890, when he was sixty eight! Frederick Ayer lived to be 95, passing away in 1918 in Thomasville, Georgia, known as “Yankee’s Paradise” for the number of northern industrialists who had winter homes there. One of James’s daughters married George Patton, the famous American commander in World War I. In 1909, William Wood honored his father-in-law by naming his most architecturally prominent mill after him. Below: Illustration of the original Ayer Mill complex from a company brochure, 1912 The Ayer Mill The following is a description of the Ayer Mill in a wonderful study of the architectural heritage of the lower Merrimack Valley by Peter Molloy (published 1978 by the sadly now defunct Merrimack Valley Textile Museum): “The Ayer Mills were designed by Charles T. Main Architects and built for the American Woolen Company as that firm's third worsted mill in the city of Lawrence. The mill was named for Frederick Ayer, a Lowell patent medicine manufacturer and the father-in-law of William Wood, the President of the American Woolen Co. The Ayer Mill manufactured worsted suitings and every operation in worsted manufacture was accomplished within its two mill buildings and dye house. An underground tunnel connected the Ayer to the Wood Mill, which was situated within 200 feet of the Ayer. During the 1950s the American Woolen Company ceased operations, and the Ayer Mill was tenanted to a number of small concerns. The dyehouse and boiler-turbine house were destroyed to create a parking lot. The boiler-turbine house contained eight 600 HP boilers and two 2. 5 MW turbo-generators. The dyehouse was 2 stories, brick, 90' x 126'. Of the two remaining mill buildings No. 1 is brick, 6 stories in height, 123' x 595'; No. 2 is 7 stories, brick, 123'x329'. The 2 mills are connected at the east end by an 8 story building, 40'x81', which contains water closets and stairways. Another building, 40'x81', connects the west ends of mills 1 and 2. This building was used as a stair and elevator tower. Above the roof level of this building rises a 40' x40' brick tower, the weather vane of which is 267' above street level. In the tower was a 20,000 gallon water cistern, a bell, and a clock with 4 illuminated dials each 22' 6" in diameter. The buildings were decorated with elaborate facades in a neo-Georgian style, with pediments, granite coursings, and Palladian windows. The buildings are among the most highly styled 20th century mills in the United States. In 1910, the mill's first year of operation, it contained 75 worsted cards, 80 combs, 45,000 spindles, and 320 broadlooms. It employed over 1,000 workers. Although situated near the Essex Company's South Canal, the Ayer did not utilize water turbines, but it did use water from the canal for process and boiler water.” Below: Frederick Ayer grave, Lowell, Mass. (Source: Find A Grave)(Note the famous "Ayer Lion" in the Lowell Cemetery is James's grave) |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed