|

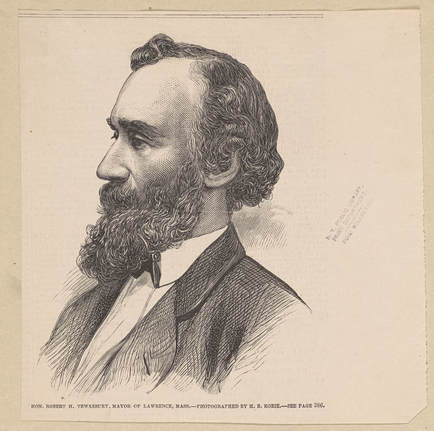

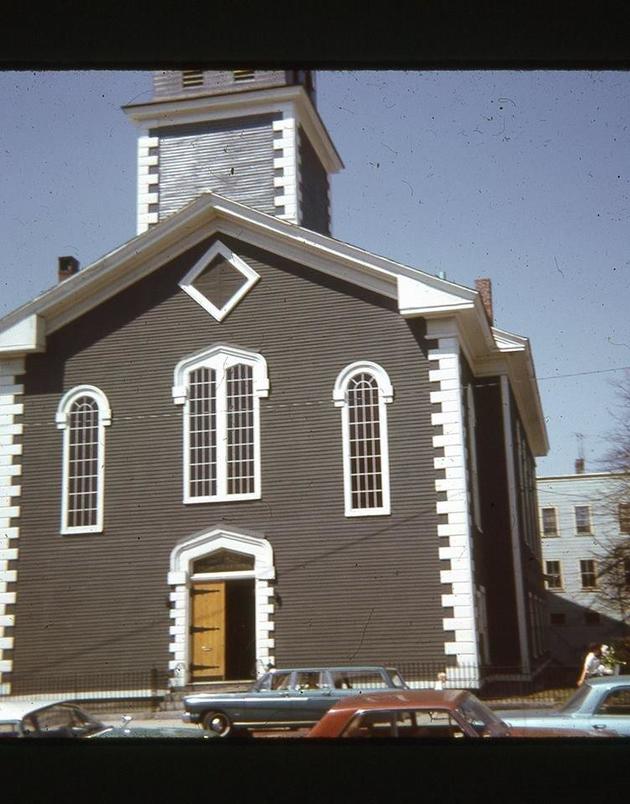

If you’re over forty, you probably remember bumper stickers like this all over Massachusetts: Among persons of Irish descent, support for the Irish Republican Army (IRA) was widespread, even if it was superficial. Somehow it was okay to like Princess Diana and Irish republicans… The IRA story was easy to understand. The British army was an occupying force. IRA men were freedom fighters, naturally fighting for a unified Ireland. British empire, bad. Freedom fighter, good. It’s all very romantic. Almost nobody from the area knows the story of the “other side”, the so-called Ulster Orangemen, who also made the region of Ulster their home. They were fighting for minority rights just as much as the IRA. Below: Logo of the Ulster Defence Association, paramilitary group The history of the Orangemen in a nutshell Ireland was ruled by the English crown starting in the 1500s. In the early 1600s, Scotland was technically still a separate kingdom. The English king had a problem. What to do with all those pesky Scots who lived on his side of the English-Scottish border? They kept trying to rise up against him. Solution: deport them to Ireland. These “Scots-Irish” (Americans like to say Scotch-Irish) were given land and rights in the province of Ulster, which was called a Plantation. They were supposed to raise sheep and pursue other productive ventures. Some of them soon left Ulster and settled the hillbilly regions of the United States. That’s another story. The ones who remained in Ulster had a tenuous relationship with the English powers. They refused to kowtow to the Anglicans who ran everything. Instead, they followed a very Calvinistic form of Presbyterianism. Although they had more rights and wealth than the Catholic population, they were an often-second-class minority within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Below: Political Cartoon from 1913 Regarding Ireland "Home Rule" When Ireland began to break away from Great Britain, the Ulster Scots leveraged their close-knit status as a political force. They won the separation of most but not all of the Ulster province from independent Ireland. The section in which they were a majority remained with Great Britain. The Ulster Scots saw themselves as a beleaguered minority of Ireland proudly clinging to their traditions. The British crown was now their protector, hence their extreme loyalism. The Orangemen One of the big traditions among Ulstermen is a commemoration of the Battle of the Boyne (July 12, 1690). In this battle, Protestant William of Orange, who rule as co-regent with his wife Mary II (hence the reign of William & Mary), defeated the deposed King James II, thus thwarting James’ failed bid to restore Catholicism to Great Britain. To commemorate this victory, Orangemen hold marches. During the “Troubles” of Northern Ireland, from 1969-1998, often these marches were designed to provoke their Catholic rivals, just as republican (meaning pro-Republic of Ireland) countermarches were designed to provoke Ulster communities. Technically, the Orangemen are a fraternal organization, comprised mainly but not exclusively of Ulster Scots (some are descended from English settlers of Ulster). It was technically founded as a brotherhood for all Protestants, in 1795 in County Armagh in Ulster. Below: Typical procession of Orangemen in Northern Ireland, July 12, 2016. PHOTOGRAPH BY Michelle McCarron. What does any of this have to do with the Merrimack Valley?? On July 12, 1875, the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne, a group of self-styled Orangemen held a picnic on the banks of the Merrimack River in Methuen. When they returned to Lawrence by way of steamer to Water Street, they were met a mob of 200 Irish Catholics. A riot erupted, and police fired at the mob. Here is the coverage from the New York Daily Herald: “Lawrence, Mass. – A serious riot occurred in this city to-night, resulting from an outbreak made by a mob upon the members of a lodge of Orangemen returning from celebrating the ‘Battle of the Boyne’ at a picnic at Laurel Grove, four miles up the Merrimac River. Orangemen from Lowell, Woburn and other towns participated at the picnic, which passed off quietly, and no trouble was anticipated when they dispersed for their homes, though some threats had been made in the morning and some of the men carried firearms in consequence. MOBBING THE LADIES About a dozen Orangemen, with ladies and children, disembarked at eight P.M., at the steamer landing on Water street, and started to walk up town. A crowd of several hundred Irish were at the landing and followed them, shouting and jeering. When they arrived in front of the Pacific Mills, the crowd commenced throwing stones, one of the ladies being struck three times and badly hurt. All the party were more or less injured by missiles thrown at them during their half mile walk to the police station, whither they went for protection. Four of the men had on regalia, which particularly incensed the mob. One of the men was severely hurt about the head and had his sash torn from him THE MAYOR JEERED AT On their arrival at the police station word was sent to the Mayor [ed: Robert H. Tewksbury], who soon arrived at the scene and undertook to disperse the mob of men and boys, but without avail; the cries and jeers of the mob drowned his voice. The Mayor, with a squad of police [editorial note: who were probably mostly Irish Catholic!], then started to take the party through the crowd to their homes. SHOWERS OF STONES Essex Street, through which they had to pass, was at this time filled for half a mile with the mob. Showers of stones, bricks and other missiles was [sic] hurled at the party as soon as it appeared upon the street. With the exception of the Mayor every one of the party was hurt. Policeman Gummel was knocked down and badly hurt. James Sprinlow, who was endeavoring to protect his brother’s wife, was knocked down, received a terrible wound in the head from a brick. At the corner of Union and Spring streets the mob made a furious onslaught of the party, when nearly all the police and Orangemen were knocked down. The latter then, in self-defense, drew their revolvers and began firing on them on the mob, who were shouting ‘Kill the damned Orangemen.” THE WOUNDED The firing quickly dispersed the mob, who scattered in all directions. It is impossible to learn the accurate result of the shooting. So far as known no one was killed. Two men, one woman and a boy twelve years old, were wounded; none seriously. Of the Orangemen twelve were wounded by stones and bricks, some of them quite seriously, and four policemen were more or less hurt. COURAGE OF THE MAYOR The riot lasted two hours and a half, and extended over a route of a mile through the most thickly portion of the city. It is the most serious affair of the kind that has occurred since 1852 [sic? Is this right? I thought the anti-Irish riot was in 1854], and is condemned on every hand as most unprovoked. The courage of the Mayor undoubtedly saved many lives.” Below: Robert Haskell Tewksbury (1833-1910), Mayor of Lawrence in 1875 Mary O’Keefe, whom I have written about, condemned the riot. She specifically cited the efforts by Irish Catholic clergy to distance themselves from the events. “And now we come to an event which we are doubtful about mentioning in a sketch of Catholicity in Lawrence for testing as we do, that Catholicity had no share in it. We refer to the ‘Orange riot’ which took place on the 12th of July, 1875, the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne, and was, by an accident, very largely advertised all over the country, and, of course, ridiculously exaggerated. However, lest we should be understood as acknowledging, by our silence, the truth of these reports, we here insert a card signed by the Catholic clergy of Lawrence, and published, at the time, in all the local papers. It expresses not only their sentiments, but those of all others in the city deserving the name of Catholics. “We, the undersigned, Roman Catholic clergymen of Lawrence, desire to publicly make known our condemnation of the riotous proceedings of last Monday evening. We do not consider as Catholics, in the proper meaning of the term, those who participated in the disturbance of the public peace, and who, by their shameful conduct, sullied the fair fame of our city. We teach our people good will towards all men, and we strive, by precept and example, to impress upon them the importance of faithfully observing the laws. We trust that the few ruflians who, under the name of Catholicism versus Orangeism, have created such bad feeling and given rise to so much trouble, may be made to feel the enormity of their crime. – SIGNED W. H. Fitzpatrick, Pastor of the Immaculate Conception Church; J. H. Mulcahy, Asst. Pastor of the Immaculate Conception Church; Jno. P. Gilmore, D. D. Regan, J. A. Marsden, O. S. A., Pastors of St. Mary’s Analysis and Questions What I would like to know: were these marchers really Orangemen, meaning they were really of Ulster descent? I have never heard of any Scots-Irish living in Greater Lawrence. I asked the Lawrence History Center, who have a redoubtable collection of materials related to dozens of different immigrant groups to the area. They have nothing on Scots-Irish, Ulstermen, Orangemen or anything similar. (There was however a large Scot-Irish settlement in Londonderry, New Hampshire - however, this town is probably too far away to have been the source of these marching "Orangemen".) I can’t help but think the march was of anti-Catholic types, of which there were still many (soon I hope to write about the Catholic school controversy of 1888 of Haverhill). But more research is needed. If anyone’s ancestor was a member of the Grey Presbyterian church in Lawrence, it would be great if you could contact me about the origins of your ancestors. Below: First Presbyterian Church (The Grey Church), 315 Haverhill Street(?), Lawrence, Mass.

0 Comments

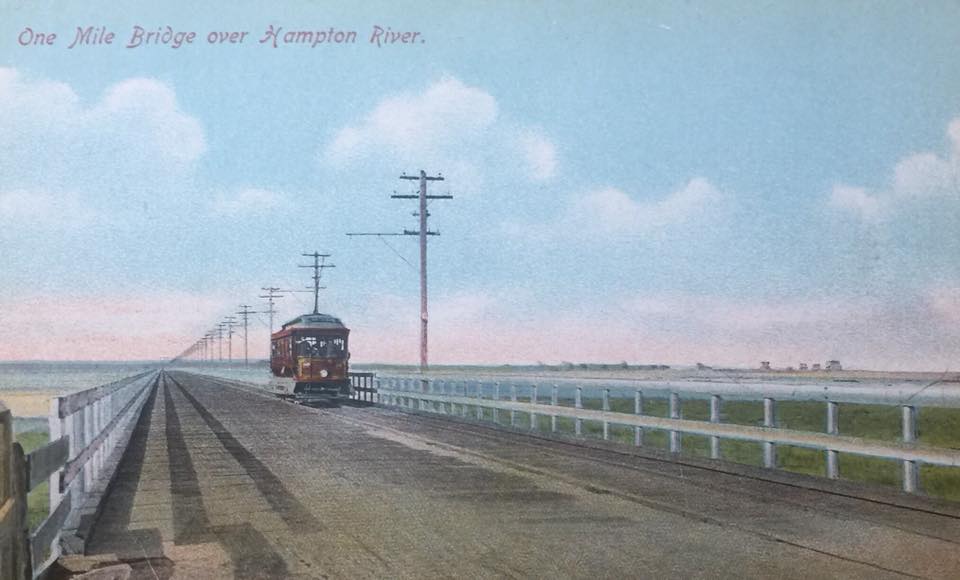

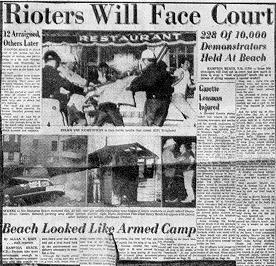

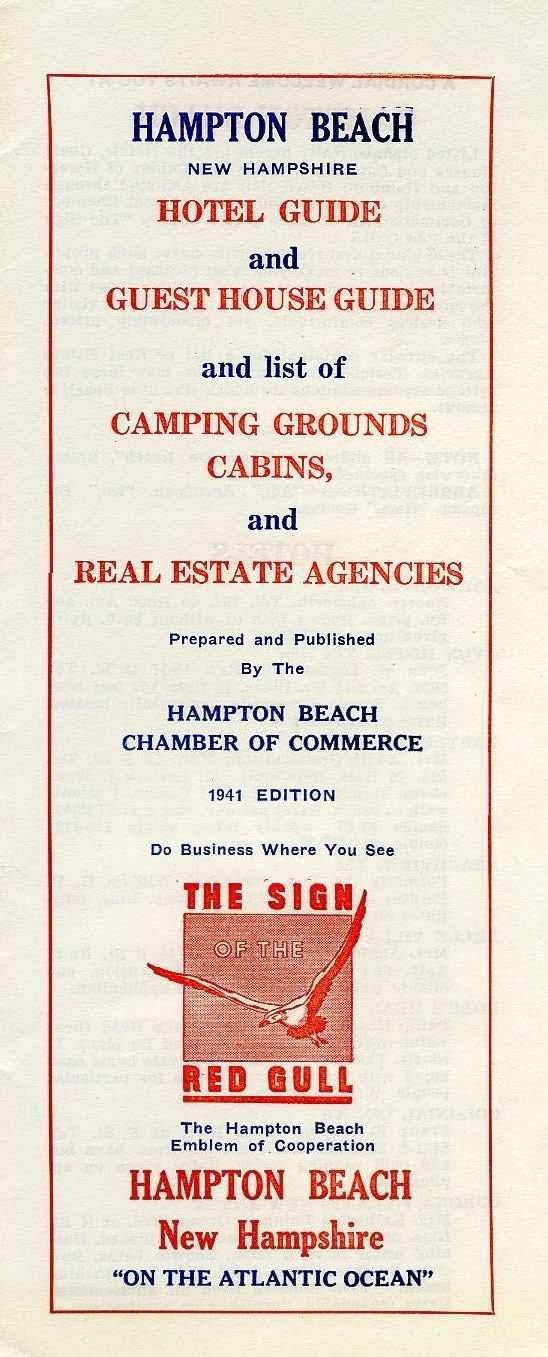

Above: Hampton Beach along the seawall near Concord Avenue, circa 1946. My father is on the far left. Grandfather standing right. Hampton Beach, N.H. holds a central role in my family's history. My maternal grandparents owned hotels and roominghouses there into the early 1960s, such as the SeaCoy right on the boardwalk (now the main branch of Blink's Fried Dough), and the Sunrise Motor Court, New Hampshire's first actual motel built circa 1920; and on my father's side, numerous uncles and grandparents had cottages that were the locus of much family activity every summer, on Concord Avenue just off the beach. I spent a lot of time there as a kid, visiting uncles on both sides who had family cottages there. Above: Steetcar to Hampton Beach, circa 1910 Even though the streetcars started to disappear in the 1930s, replaced by automobiles, the travelroutes had been established between the mill towns of the Merrimack Valley and these beach resort areas, leading to a particular culture of the area. Whether you went to Salisbury or Hampton depended on a variety of factors, sometimes outside of your control. Italians almost universally went to Salisbury, as did most French Canadians. This was partially due to a prejudicial attitude held by the fathers of Hampton Beach, who did their best to exclude certain groups. (See the report http://www.hampton.lib.nh.us/hampton/history/randall/chap3/randall3_2.htm). Hampton's town fathers apparently tolerated the Irish, although only the "better sort." In any case, by the early 1960s, Hampton had the view that "Salisbury is inclined to be classed as a honky tonk by Hampton's advocates, who have always prided themselves on keeping Hampton Beach a family resort, free from liquor, ferris wheels, roller coasters and the other gimcracks which can clutter and choke a vacation community." (Report of the Hampton Beach Office of Juvenile Delinquency and Youth Development on the 1964 Riot). Yet this snooty, "middle class" attitude of Hampton Beach did not prevent a series of increasingly serious youth riots from breaking out each year starting in 1960, culminating in the 1964 Labor Day riot. In that event, between 2,500 and 10,000 youth clashed with "40 local police, 68 auxiliary police and 85 state police, ultimately assisted by the Rockingham County Sheriff's Department, the New Hampshire National Guard and a contingent of Maine state police." Below: Newspaper coverage of the riot. Source: Hampton Historical Society "Miraculously, no one was killed, although both police and rioters sustained extensive injuries. The expressed desire of the youth to burn the Hampton Beach Casino was thwarted, but two small buildings were burned down by Molotov cocktails, and approximately 155 youths were arrested." As the report in the riot noted, on an average summer day there may be 25,000 to 30,000 persons at Hampton Beach. And at peak crowd periods, such as holiday weekends, there may be 100,000 persons at Hampton Beach. Furthermore, "Of the total population, probably 75% of those at the beach center and 50% of those in the entire Hampton Beach area are under the age of 25. Thus there may well be 10,000 to 15,000 young people at the resort at any given time during the summer, or up to 50,000 or possibly more on holiday weekends." The part that interests me: Most of these youth were presumably from the mill towns of the Merrimack Valley: Lowell, Lawrence, Haverhill. Was their boisterousness related to local culture? Or were the riots more about "youth culture", the first hint that the "Baby Boomers" were going to be different, were going to expect to do things their way. How different was this riot from the Lawrence, Mass. riot of 1984? One of the most interesting aspects of the post-riot report is the very detailed assessment of the various youth cliques that prevailed at Hampton Beach in the summer of 1964. "1. The "C" Street gang" - young patrons and employees of the Patio Restaurant at the Ashworth Avenue end of C Street and of the Tiki Restaurant (in 1964 the Troll Bridge) near the Ocean Boulevard end of C Street. Probably 25 to 50 young people from this group were on the beach at all times through the summer; another 250 to 300 would come and go during various periods, with the peak on weekends. When a special party or outing - frequently a luau away from the Hampton Beach area - was held, nearly everyone from this group would be on hand. Of the various cliques on the beach it was the most cohesive, the most happy-go-lucky, probably the most casual in its attitudes towards sex and liquor. Around this group - probably to a greater extent than with the other groups - there clustered a collection of hangers-on, particularly around the Tiki Restaurant. Of all the cliques on the beach the C Street gang was most "in." Perhaps "clannish" would be an appropriate term to apply to this clique, for on the occasion of its parties attendance was by invitation only; those not thoroughly accepted were pointedly omitted. Perhaps some of the hangers-on gave the C Street gang a worse reputation than it deserved, for although the Tiki and the Patio were never centers of trouble from a police viewpoint, it should be noted that some of the tougher kids of the beach did hang out there. The C Street gang - and indeed all the other home-based groups on the beach - took a rather conspicuous stance against riots and rioters. These people came to Hampton Beach for a good time, and primarily they wanted to be left to their own devices. Specifically in the 1964 riot they had taken an active part in defending their own territory against the rioters and had prevented damage for the length of their street. Throughout the summer, many members of the C Street gang were on excellent terms with the police and the rapport was mutual. 2. "The Renwood Group", based around the employees of the Renwood Dining Room and Gift Shop, the Moulton Hotel and the Carrousel luncheonette, all properties of the Downer family. In this group there was a similar cohesive spirit. The individuals in the group were probably a little older - more of a college age - than those on C Street, and their behavior and attitudes a little more conventional. Of all the factions on the beach this one was least active in its participation in CAVE" (the Committee Against Violent Eruptions, which had been formed by the Hampton Beach police in response to the less severe 1963 riots, often referred to rumbles). 3. The Dunfey group, employees of Dunfey's Restaurant and various other beach enterprises and their friends. Through the years as the Dunfey enterprises have expanded and the Dunfeys themselves have had less opportunity to participate personally in their beach enterprises, their employees have become a less close-knit group. Nonetheless, this was a distinct faction in the beach society, both overlapping and in competition with the C Street group. For instance, during the summer of 1964 there was considerable horseplay over the "kidnapping" of the Dunfey piano by the habituees of the Troll Bridge and its subsequent recovery. 4.Casino employees - a distinct group in itself, especially around the employee domicile known as the Gink, but also fragmenting and taking part in the affairs of the various other cliques. The remainder of the beach society was considerably more amorphous, composed of day visitors who came and went and smaller groups looking for beach outings or dates. As a rule there was very little cohesion along home-town lines. In some few instances there is contact between various members of these several groups during the winter season, but for the most part it centers around the beach itself, starting about mid-April and ending rather abruptly after Labor Day. To some small extent there were some cultures around the few places of teenage entertainment on the beach. For instance, the Seagate Ballroom, running rock and roll bands four nights a week, consistently attracted a crowd of 14 to 16-year old youngsters who may have had other contacts during daytime hours. The Onyx Room, a teenage nightclub a mile to the north of the beach center, also had its own following, although here again there was overlapping, since much of its clientele obviously came from the C Street group." Such an elaborately detailed, fine differentiation between and among the different youth cliques suggests that this "exuberance" was a youth-based event, rather than a class-based event. In fact, many of the reports emphasized that youth who came to Hampton dropped their hometown allegiances and did not run in cliques based on what town they were from. The post-riot study noted "it was quite clear that Lowell, Massachusetts, far outstripped any other community in its representation of young people at Hampton Beach." (Lowell being the biggest mill town.) Cover of the guidebook listing my grandparents' properties in their heyday

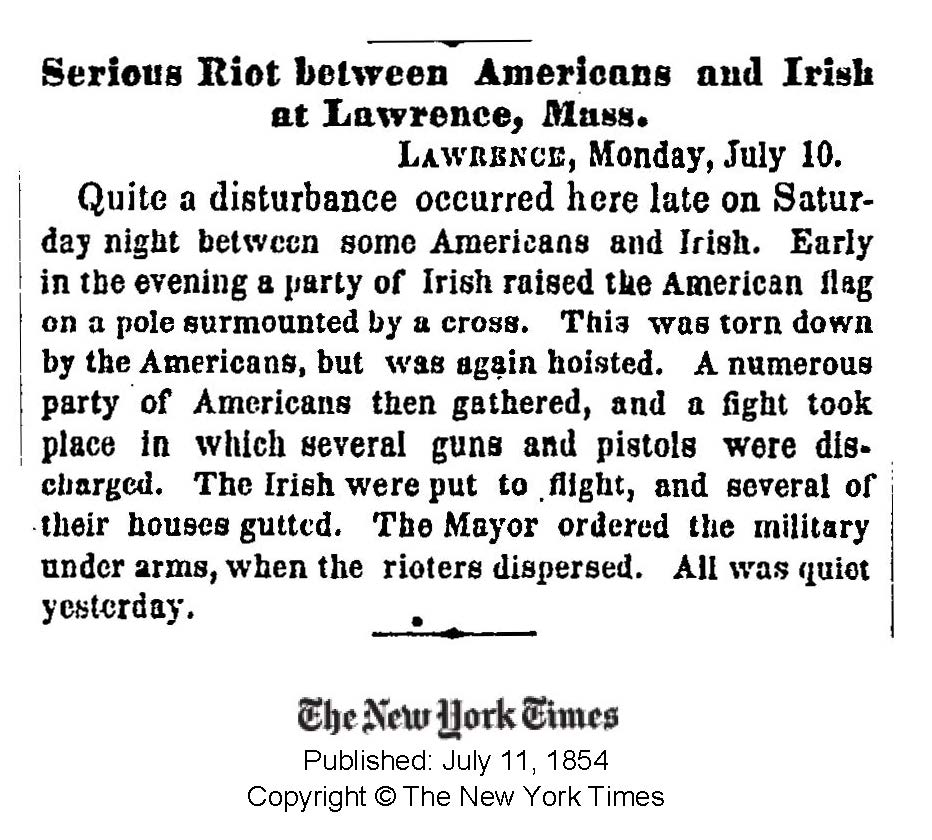

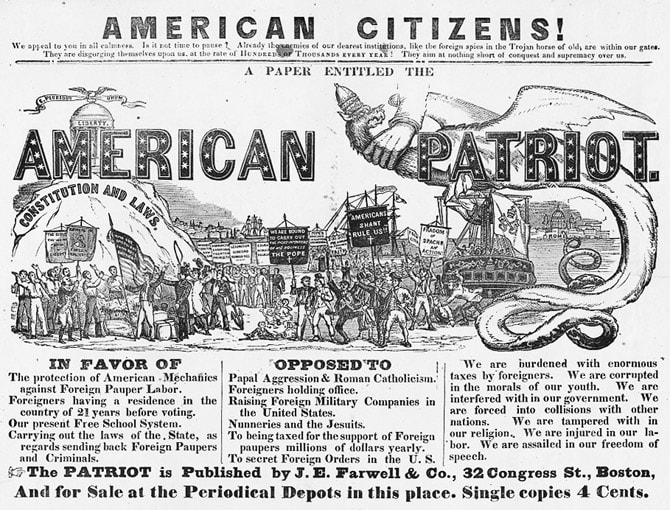

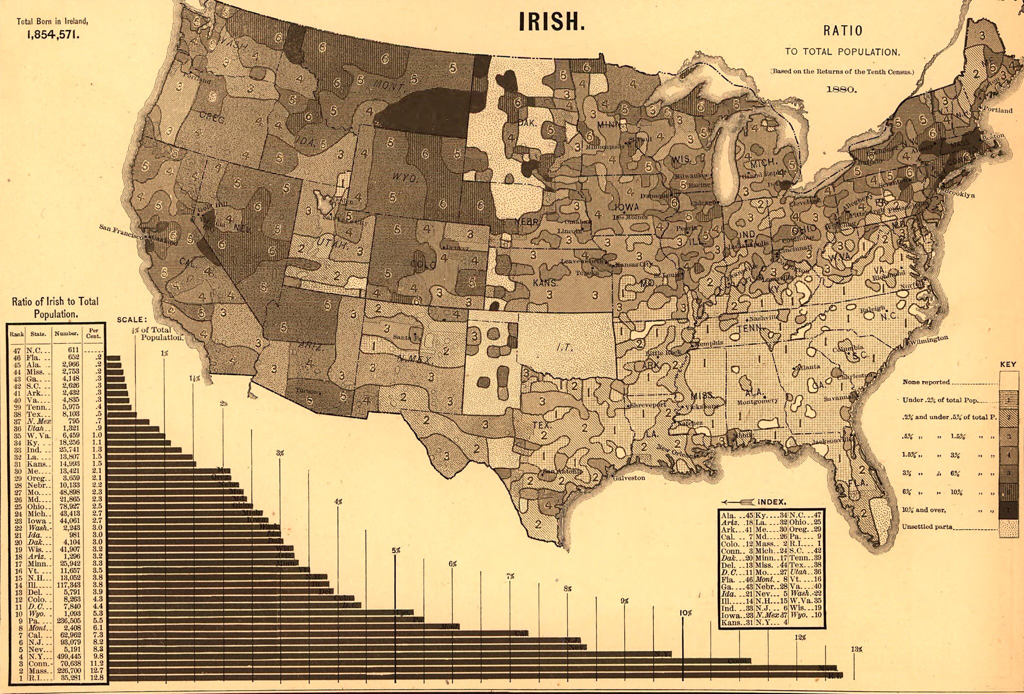

In previous blog post, I covered the Lawrence "race riot" of August 1984, which was essentially between a newcomer immigrant group, "the Hispanics", and established natives. Who says history never repeats itself? A century-and-a-quarter earlier, another riot occurred in Lawrence, between a newcomer immigrant group, "the Irish", and established natives. See news coverage above in the New York Times, July 11, 1854. The Lawrence riot of that July 11 was part of a wave of violence aimed at recent Irish immigrants. It swept New England in the summer of 1854, at the height in these parts of the Know-Nothing movement. Know-Nothing politicians stirred crowds with hysterical speeches, about how the Catholic religion was incompatible with American values. "They only answer to religious law and do whatever the Pope and the priests tell them!" "They oppress their women by putting them in convents!" These were the kinds of statements made by the Know-Nothings. It reminds me of hysterical tirades aimed at the supposed incompatibility with American values of the religion of another group of recent arrivals. Just substitute "the commands of the Pope and the priests" with references to Sharia law to see what I mean. The existence of separate religious schools run by and for Catholics particularly incensed many natives, and led to continuous political and court battles through most of the nineteenth century. The "School Question" will be the topic of another blog entry. Think about the context of this anti-Catholic animosity. I'm not defending it, but perhaps it was understandable. Your average New England Yankee had for two centuries been fed a diet of how horrible "Popery" had been, a belief borne out of Protestant experiences with the Counter-Reformation and the religious wars that plagued Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Virtually all New England churchgoers of the time would have shared a staunch belief in the supposed corruption of the Catholic Church, as was finally upended in the Reformation. This was one of the few beliefs that unified the various Protestant denominations that flourished in New England by the 1840s, Congregationalists, Unitarians, Baptists and Methodists being the main ones at this time. Furthermore, very few of these denominations had any liturgy or ritual to speak of in their worship. Also, there were vague collective memories of the French and Indian attacks, led by Jesuit warrior-priests like Father Sebastian Rale coming down from New France (i.e. Quebec) with bands of wild Abenaki Indians to slaughter English villagers. In this context then, imagine how America's first wave of Catholics, the Irish, appeared. Their worship was in a strange language, Latin. This language would have scared Yankee listeners, as it signified the supposed corrupting influences of Rome on true Christianity based solely on original biblical texts, in addition to being completely foreign. Moreover, the Catholic mass (their worship ritual) usually lacked a sermon, full of textual exegesis, which was the mainstay of Congregationalist worship; nor did it have any of the evangelical personalizing of the relationship between the individual believer and Jesus Christ, which, since the Great Awakening in the 1740s, prevailed in the non-establishment Protestant denominations such as the Baptists and later the Methodists. Instead, Catholic worship featured a man in weird robes (the priest) facing an ornate altar, making strange gestures and repeating a bunch of Latin phrases in a prescribed order, while the congregation chanted phrases in Latin in a prescribed order, kneeling, sitting and standing in turn. Imagine how frightening a group of worshipers all kneeling and bowing in unison could be! And then there was the intense scrutiny of convents and nuns, who were assumed to be under oppression and even sexual slavery, with their covered heads and existence behind closed doors. The Ursuline convent in Charlestown, Mass. was burned down by a mob in 1834 on suspicion that women were being held there against their will. And practices like praying the hours (in which devout Catholics visibly pray five times a day at prescribed hours using prescribed prayers based on a calendar), also set off suspicion and animosity, as did its simpler sister ritual, saying the rosary. Below: the cover of the American Patriot, a Boston-based Know-Nothing newspaper, 1854 In addition to the anti-Irish riot in Lawrence, many other New England towns and cities had similar riots that summer: Bath, Maine (in which a Catholic church was burned down); Ellsworth, Maine (in which a priest was tarred and feathered); Chelsea, Mass. (in which a Catholic church was attacked); Dorchester, Mass. (in which a Catholic church was destroyed by dynamite); and Norwalk, Conn. (in which St. Mary's catholic church was set on fire and its steeple sawed off), among other places. In Manchester, New Hampshire on July 4, 1854 a skirmish between some Irish youth and some "natives" over a bonfire that the former group wanted to light escalated into significant violence. The local newspaper account stated that a "large number of men, armed with clubs and other destructive implements, about day-break, commenced an assault upon all the Irish houses in that neighborhood. Some ten or fifteen were pretty thoroughly dismantled—the doors and windows of many of them being completely stove in. The rioters next proceeded to the Catholic Church—just re-built at great cost, and probably the handsomest in the State—and continued their fiendish work. …" (Manchester Union Democrat, July 5, 1854). These anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic sentiments swept the Know-Nothing American Party into power in the Massachusetts state legislature in 1854. "While much of the American Party’s platform was socially progressive, its highest priority was reducing the influence of Irish Catholic immigrants, and the party became the home of wildly divergent social movements attempting to organize under one political umbrella....The Massachusetts Know Nothing legislature appointed a committee to investigate sexual immorality in Catholic convents, but it was quickly disbanded when a committee member was discovered using state funds to pay for a prostitute." (Historic Ipswich blog entry on the Know Nothings) By 1858, however, the new party was a spent force, and was defeated in almost all local and state elections. It also did little to thwart the continued growth of the Catholic Church in Massachusetts and New England, as Irish immigrants continued to pour in while their church organized itself under Irish leadership. Later, Irish domination of the Church hierarchy led to resentment by other, later Catholic immigrant groups, such as Italians and French Canadians - that topic will be covered in a blog entry about "National Parishes". Map showing concentration of Irish-born in 1880. Note Massachusetts. My own theory is that the Catholic Church of the Irish variety flourished in New England despite considerable native animosity in from the 1830s through the Civil War, because of a long history in Ireland of persevering under conditions of adversity and oppression.

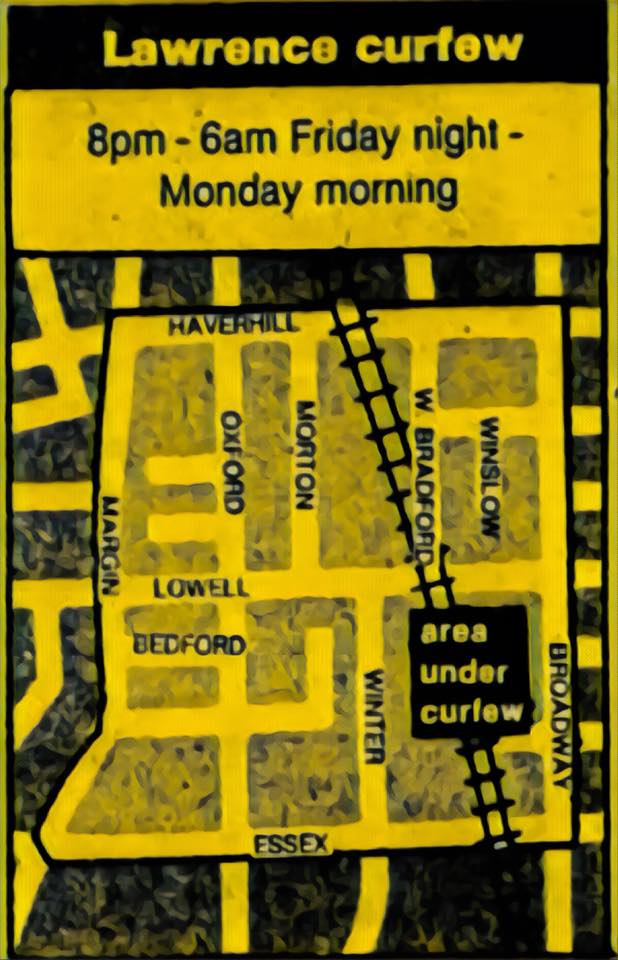

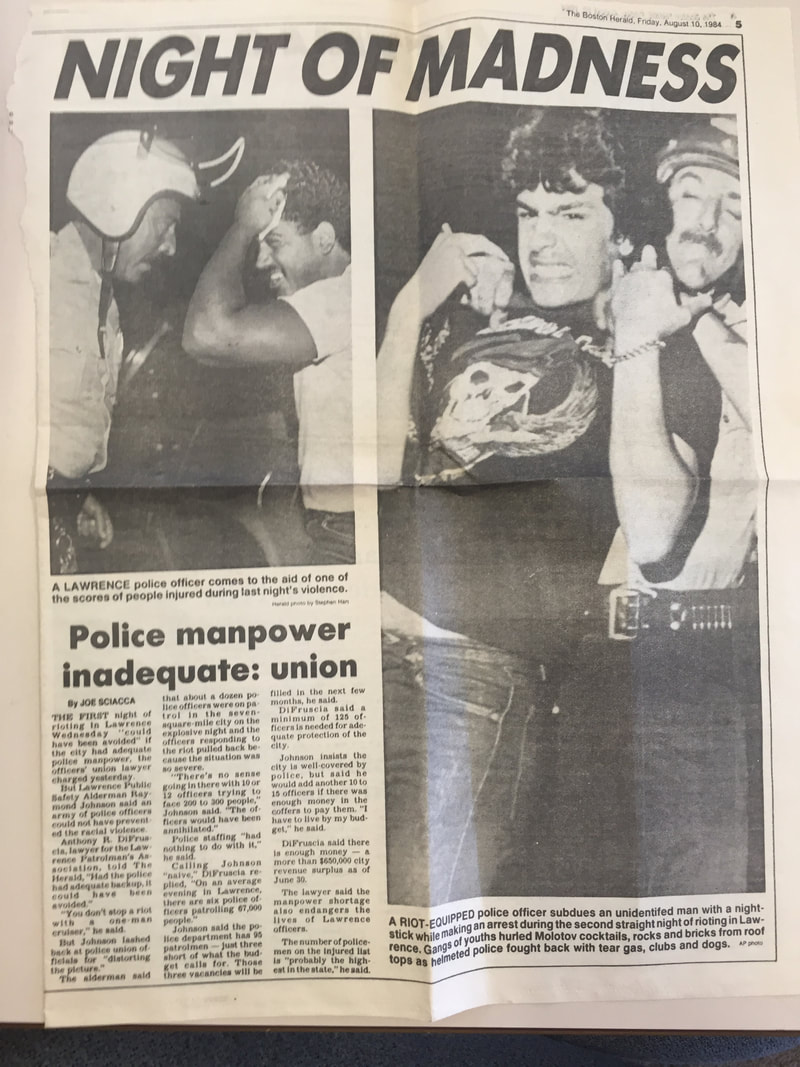

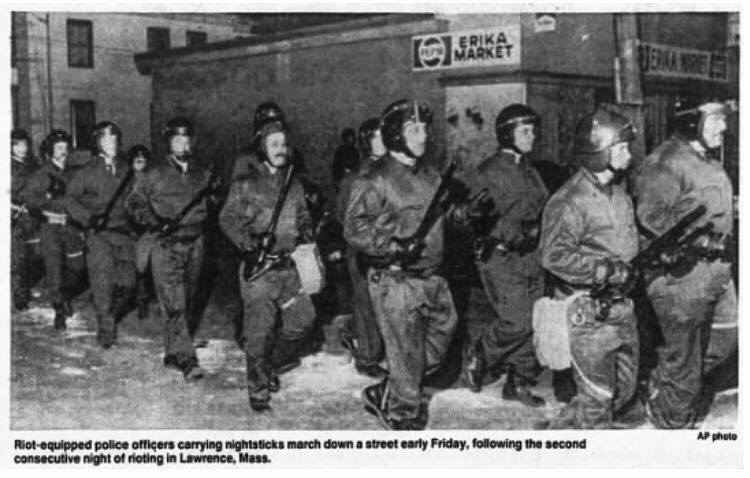

Revised 7-19-18 Above: Leaflet showing area under police curfew after the second night of rioting The riot started the night of August 8, 1984 near the intersection of Oxford Street and Haverhill Street, and flared up again the next night. News accounts describe the area of the riot as "Lower Tower Hill", however, it really occurred right below Tower Hill in the flatlands that end at the aptly-named Margin Street. The unrest spread not up the hill (which would be to the left on the map) but along the base of the hill, over to the Merrimack Courts housing projects on Essex Street, and then to the Hancock projects beyond. Below: Coverage of the riots in the Boston Herald In my view, the riot was not a very big disturbance, albeit one that local police could not get under control on the first night. It happened less than half a mile from my house with no immediate impact beyond a narrow zone running between Broadway and Margin Street along the base of Tower Hill, across an area of probably less than ten acres. I have suggested that it was more like a large-scale rumble, and not a "riot" in the same sense as the gigantic Detroit riots or Watts Riots which ranged over hundreds of acres destroying a lot of those cities. Even locally, compare the 1964 Hampton Beach riot, which involved up to 10,000 youth battling state police from New Hampshire and Maine and many neighboring towns. This riot was more of a local affair. Sometimes the rioters even cooperated, for example when they were dividing the loot: “At 11:00 PM rioters broke into Pettoruto’s liquor store. The Eagle-Tribune reported that at first the two groups [presumably whites and hispanics] fought over the liquor, but then they cooperated to divided it up and share it, after which a ‘lull followed with a lot of public drinking.” This is from Llana Barber's book Latino City, mentioned below. The author notes dryly, “This odd reprieve could not have been long lived, because by 12:15 AM, the liquor store was on fire.” A theory about the riot: I have a theory that the riot was directly related to the 1982 "desegregation" of the two nearby schools, which destabilized the geographic social order by giving kids from the "wrong" side of an invisible line a newfound right to pass all the way to the top of the hill, which at that time was another world. The two schools involved were the Hennessy School down on Hancock Street next to the projects; and the Bruce School (my school from kindergarten through 8th grade), at the top of the hill. School desegregation upset longstanding geographic hierarchies of the area, which were based as much on social class as ethnicity or race. When I was a kid, in the single family homes and duplexes near the Reservoir or up the hill from the Bruce, families were "middle class". The parents of about half my neighbors were college educated, many of them teachers or working for the city; and the other half owned small businesses, such as plate glass or oil delivery, or sold insurance, or did other respectable, responsible things. Nearly everyone owned their home. Going further down the hill, the homes were multifamily and the youth were often rougher. Nobody went to college. Almost everyone rented. Dads seemed to be in motorcycle gangs, fixed cars, worked as roofers. Down at the bottom, where the slope ended and the terrain flattened out, were fresh-off-the-boat immigrants...most recently from the Dominican as well as Puerto Ricans who had started arriving in the early 1970s. After the 1982 desegregation, the population of the Bruce School changed dramatically. In a short while, many of my friends switched schools. The nearby parochial school on Ames Street, St. Augustine's, had a couple banner years of attendance (it is now closed). The Bruce school was to be flooded with kids from down the hill. To entice some middle class families to stay, a "Magnet School" was created in a neighboring building, a former synagogue that had relocated to Andover when the congregation all moved away in the 1970s and early 1980s. (The J.C.C. fifty yards from my house limped on, without members, before finally closing in 1990.) Despite the magnet school and the availability of St. Augustine's parochial school, the neighborhood also changed character within a couple years. The population from down the hill came up the hill, as the previous population moved out, so that the line that used to be at Margin Street moved up the hill a few blocks every year. Eventually, everything had changed, all the way over the top of Tower Hill and down the backside of the hill to Methuen. In 1985, the Hispanic population of Lawrence was 16%; it is presently around 80%, in a city that has 15,000 more residents than it did back then. I'm sure my former neighborhood is also 80% Hispanic overall. My parents still live there, up by the Reservoir. Professor Llana Barber extensively discusses the Riot in her book Latino City (2017), giving a synopsis of how Lawrence became a Latino city through and through. My review of her book is here. The poorly executed 1982 school desegregation that conflated race and ethnicity with social class, and then the riot, simple hastened a trend that would have happened anyway: Lawrence becoming a majority-minority city. In many ways, Lawrence is now a Hispanic Shangri-La, a place where people of a shared culture can live among their own, while still participating in the overall economic benefits of the Greater Boston area. The people who have moved out of Lawrence since the 1980s often look back with nostalgia on the way things used to be, and some of them unfairly scapegoat the new immigrants of Lawrence for what they see as negative change. However, I'm sure that in 30 years, when the current residents of Lawrence and their kids have also moved on, to "better" areas, they too will look back fondly on the old neighborhood in Lawrence where everyone spoke their language, listened to their music, and ate their cuisine. Below: AP photo of riot police in Lawrence. Erika Market was on the corner of Oxford Street and Lowell Street.

|

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed