|

"Kids roamed the neighborhood like dogs. The first week I was sitting in the sun on our steps, I made the mistake of watching them go by as they walked up the middle of the street, three or four boys with no shirts... the tallest one, his short hair so blond it looked white, said, 'What're you lookin' at, fuck face?'

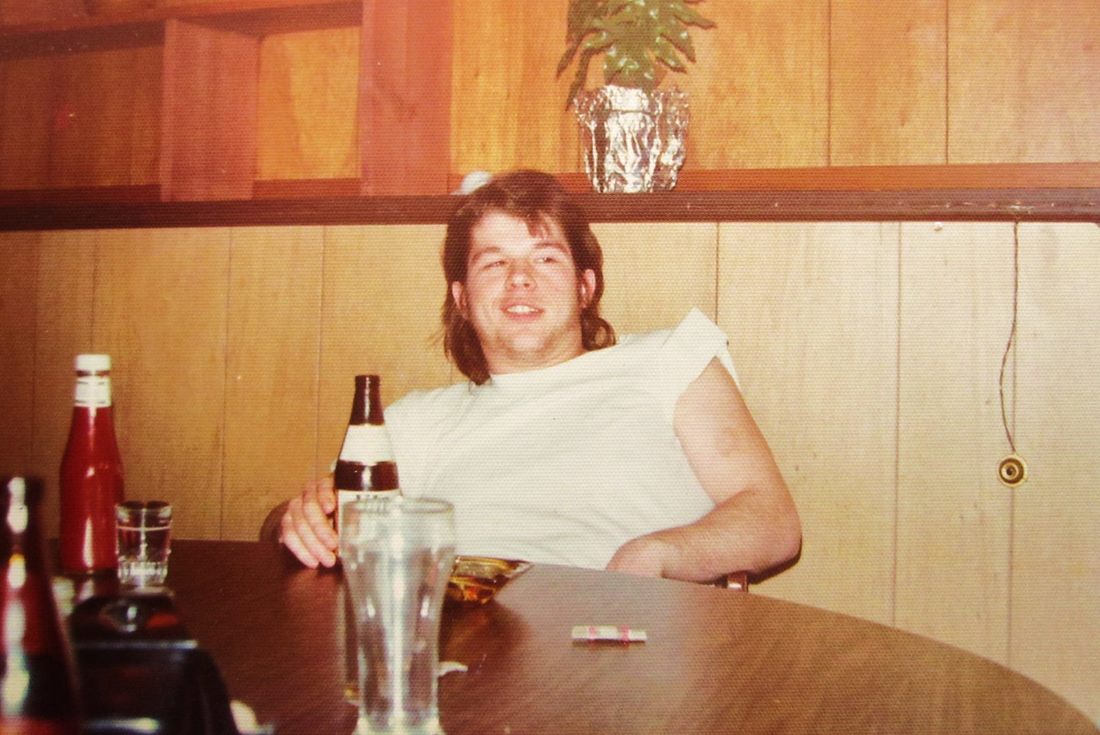

'Nothing.' There he was on the bottom step. He pushed me hard in the chest and kicked my shin. 'You want your face rearranged, faggot?'" It is the early 1970s. A 10-year-old Andre Dubus has moved into the rough, working class part of Haverhill, known as the Avenues. He quickly sets the tone with descriptions like these of his interactions with neighborhood youth. He lives on “a narrow hill street of tin-sided houses behind chain-link fences." "Plastic children’s toys would lie on the cracked concrete among cigarette butts and empty nip bottles, and on their sides here and there would be shopping carts for when the car wouldn’t start and the welfare checks came in and usually the mothers and wives or girlfriends would push the carts a mile and a half away to DeMoulas and load up with cans of Campbell’s soup, eggs and milk, bags of potato chips and cases of Coke and Budweiser, bottles of Caldwell’s vodka. Halfway down Seventh Avenue was a cluster of yellow apartment buildings, two rows of them three-deep back from the street, each three stories high. The ground around them was packed dirt worn smooth and there was a gravel parking lot scarred from rain and in the back of it, up against a field of weeds, was a green dumpster I’d never seen empty; it was full of babies’ diapers and old mattresses." A local gang of young men run an extortion racket of sorts, "men in their twenties or thirties who earned their rent by collecting it from everyone else, two or three going from door to door on the first of the month each demanding cash. Some of them were with the motorcycle gang, the Devil's Disciples..." He becomes a fighter, a lieutenant, an instigator. What ensues is four hundred pages of violence, bravado, thuggery, petty bickering, intimidation, sadism, hooliganism. He is not an outsider, rather he is simply breathing the air around him, swimming in his ocean. Dubus becomes acculturated to violence, using the metaphor of a membrane that has to be punctured by an act of will. "This was different from sex, where if you both want it, the membranes fall away, but with violence you had to break that membrane yourself, and once you learned how to do that, it was easier to keep doing it." His summary of his school captures the prevalence of violence, even in this supposed sanctuary from the street: "The slam of a locker, the slap of feet over the hard floor, the soft thudding of a fist thrown again and again into someone's face, like waxed wings flapping, then a joyous shriek of someone yelling "Fight," and we'd all all be running to them, crowding around the two or three bodies flailing away at each other in the center. In a school of over two thousand students, this happened once or twice a week." The part of Townie that most resonated with me, in what was a hard slog through 400 pages of numbing descriptions of beat-downs and delinquency, was this: Although the story takes place in the rough part of Haverhill, it could just as well have been in almost identical neighborhoods of Lowell, or Newburyport (before it was renovated) or Lawrence. Post-industrial, worn out, working class, "inner city" (white inner city) mill town. The descriptions of the chain link fences, the dilapidated triple-deckers, sounded like, for example, the streets in Lawrence down by the Spicket River, Erving Avenue, or the lowest part of Tower Hill, along the train tracks west of Broadway. And the descriptions of the rebelliousness, the anti-authoritarian punkishness, the roughness, the chip-on-the-shoulder masculinity...I knew this from kids at the Bruce School who would "see you in the schoolyard after school" at the littlest slight, who ran in gangs, whose fathers ran in more organized gangs, like the ones that congregated the Calumet Bar and ran numbers and hookers. Luckily for me, this kind of culture was usually at the periphery growing up, down the hill, in other neighborhoods...but I knew it was there. It's full of tribalism, group loyalties and animosities, even though everyone's white and probably "white ethnic", still living the vestiges of immigrant culture three or more generations in: Irish, Italian, French Canadian, Polish, whatever. Why communities of people get like this, or why they seem to have been so prevalent in places like Lawrence and Haverhill (where in some neighborhoods disagreements were settled by rumbles)...I will leave this to the sociologists. However, I think an awareness of this culture is necessary to understand things like the Lawrence riot of August 1984. From one perspective, that riot was a big rumble, except that the counterparty, as it were, wasn't another gang of white ethnic milltown punks; it was fresh-off-the boat immigrant youth from Puerto Rico (some via NYC), and the Dominican Republic, who got provoked into engaging with this kind of local culture.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed