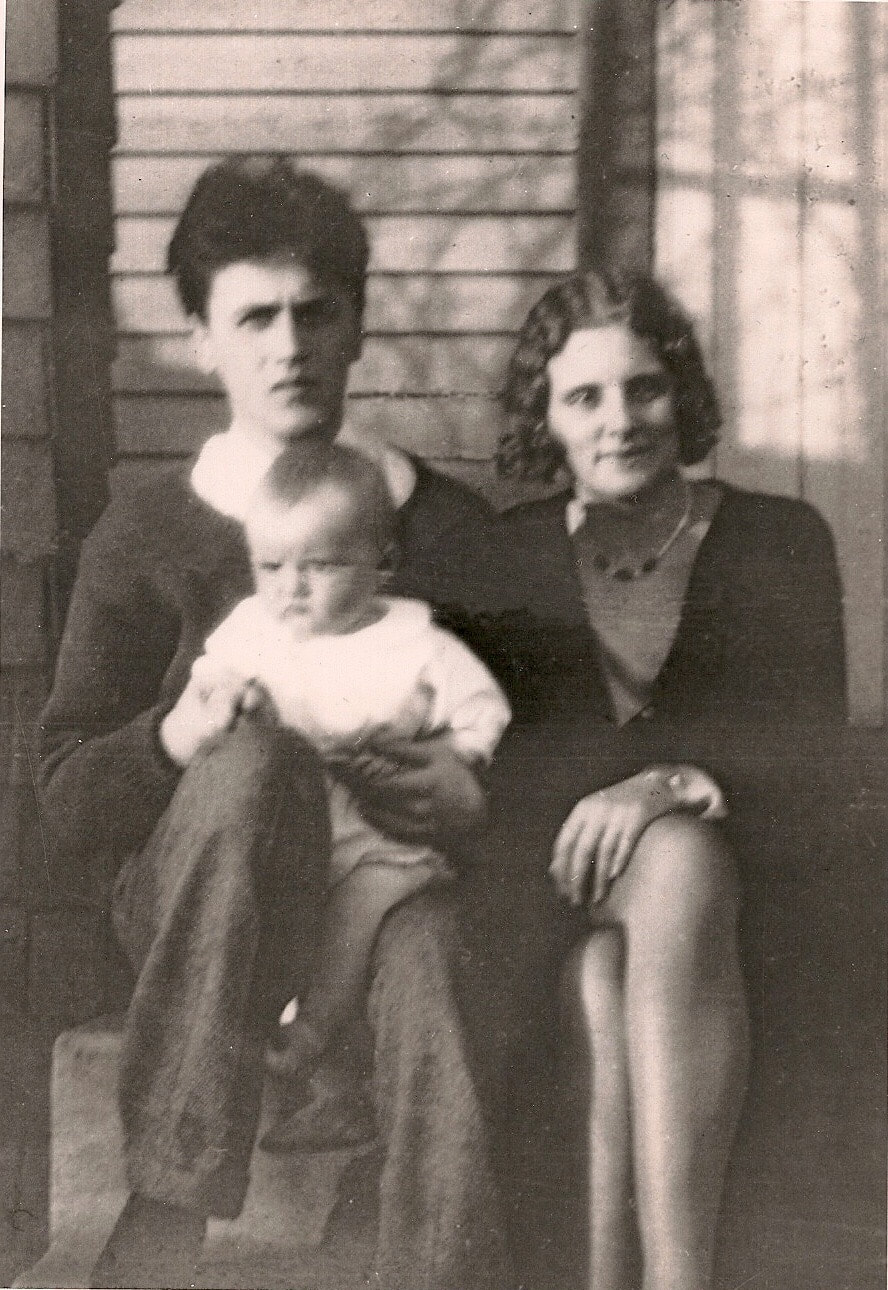

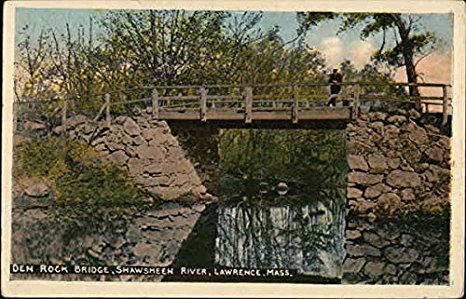

#52Ancestors challenge, week 7: My grandfather illustrates the industrial heritage of three towns2/18/2018 Below: My grandfather Clifford McCarthy, age 18, my grandmother Gladys Johnson, age 17, and my father, late autumn 1930(?). Recently, I asked my father to describe the work history of his father Clifford, who was born in Lawrence in 1912. Clifford married his high school sweetheart Gladys Johnson on his eighteenth birthday, February 3, 1930. She was four months pregnant with my father. They found a minister to do the wedding on the quick, in North Reading a few towns away. The stock market crash had been the previous October, before which Clifford's prospects seemed very different. Now, he was a married man with a family to support. Banks were failing and employers were closing. The Great Depression was descending over everything. He took his high school diploma that spring at Lawrence High and went to work. Below: The Kuhnardt Mill in Lawrence around 1930 judging by the cars in the background. This building still stands today. Source: Lawrence History Center .According to my father, "The first job of my dad’s, as I remember, from my pre-school days, was as a jig operator in the dye house at the Kuhnardt Mill by the Duck Bridge on the north side of the Merrimack River [in Lawrence]. His boss was his brother-in- law Wiliam Howarth. I heard complaints (from my mother?) that Bill picked on him." This was one of the stories of my grandfathers' employment history, working for in-laws who got him jobs. Later, he got a job with the Boston & Maine railroad through his father-in-law, who was an engineer. Years after that, in 1949, my father got a job working for his uncle Bill Howarth. It was at a dye house in Peterborough, New Hampshire. They were both working there because the mills in Lawrence were laying people off. Soon, the dye house in Peterborough also closed, and Bill Howarth moved to North Carolina to follow the textile industry south. But I digress... Because it was the Depression, there were times when my grandfather was laid off. "We received free flour from some source and my mother made "Johnny Cake” with it, which I liked," said my father. This is when New Deal programs allowed my grandfather to earn a wage. "He also worked with the WPA during the 30s. l distinctly remember a WPA arm band. I think he was involved with building side-walks, pick-and-shovel work." My father thinks he was part of the team of WPA workers that built Den Rock Park in Lawrence. Below: A bridge in Den Rock Park, Lawrence, Mass., that was likely built by WPA workers in the 1930s. The park sits at the intersection of Lawrence, Andover and North Andover My grandfather's next two factory jobs were in Andover, where by happenstance my father also was born a few years previous. "Thereafter as I remember it both parents worked a spell at the Shawsheen Mill (American Woolen Company). If this were so, my brother and I would have been living with my grandparents at 34 South. St. [Lawrence, on the Andover town line]." Below: The Shawsheen Mills in Andover in 1977, right before they were turned into apartments. Source: Andover Historical Society "I’m pretty sure the next job my father had, during World War 2, was at the Tyer Rubber Company, on Railroad St. (where Whole Foods is now). I think he was a warehouse man. As I remember he did bring home pairs of rubbers and overshoes at times. I was then in grammar school" The Tyer Rubber factory eventually was owned by Converse. Soles for their famous Chuck Taylor sneakers were apparently produced there, along with NHL hockey pucks. Manufacturing ceased there in 1977, and by 1990 the facility had been converted into apartments. As of late, there is even a Whole Foods in the front part of the facility, showing how far the town of Andover in particular has come from its quasi-industrial past! Below: My grandfather's eminently respectable parents on the occasion of their fiftieth wedding anniversary in North Andover, Mass., 1954 "The next job I believe dad had was with the B&M Railroad. I believe Grandpa Johnson, a mechanic with the B&M at the South Lawrence round house got him the job. The job was as a mechanic assistant at the round house in Boston. So this entailed a daily round trip by train. He worked there until he got laid off when the job of assistant mechanic was eliminated altogether, this was probably when Diesel engines replaced steam engines and assistant mechanics were no longer needed. I also remember him not showing on time for supper a number of nights. This occurred when he fell asleep on the train and woke up at the last stop in Haverhill. Then he would have to take the train back to Lawrence which probably got him back home about an hour after his due time." Below: My grandfather posing with other relatives in front of one of the Johnson family cottages at Hampton Beach, New Hampshire in the mid- to late- 1940s. He is lying down in front. His final job was in North Andover, at the huge Western Electric factory that was built there after World War II. "Next he worked at the Western Electric Plant in North Andover until retirement. I’m not certain what kind of work he did there, now it comes to me, I think he was a clerk in a tool crib, if you know what I mean. In any case he liked the work as I recall." "There is one more job he had," my father added. "This was as a janitor in the building [in Andover] where Phillips Academy’s school course books were sold. Now I don’t remember if he held this job before he went to work for Western Electric or after he retired. In any case I believe he worked his butt off there. It was the only time lever heard him complain about his work. He was not there for long, as I remember." Below: Osgood Landing, North Andover (largely vacant). Formerly the Western Electric Merrimack Valley Works, then an Alcatel plant. Eagle-Tribune photo. I've been told I can work like a dog, uncomplainingly. Maybe I got it from my grandfather. Even though my grandfather was a "working stiff" (as my father calls him), he regularly wore a jacket and tie when he wasn't at work. I don't know if this was a generational thing, or whether he did it consciously in an attempt to maintain some dignity despite his fairly plebeian economic status. He liked to sketch figures, including nudes copied from Playboy (an excuse to buy the magazines despite the certain protests of my fairly prim and proper grandmother). He exhibited a lot of [unmet] artistic talent that I also seem to have inherited, which is also basically unmet. Except I at least got the luxury of drawing real life nudes, when I was in the eleventh grade at Phillips Academy. Another general point: My grandfather's work history - spanning employers in Lawrence, Andover and North Andover - illustrates the free flow of people throughout an economically integrated area. One of the themes of my blog is the formerly integrated nature of "Greater Lawrence" (meaning Lawrence, Methuen, Andover, North Andover and Salem N.H.). The separate "ghetto" status of Lawrence is only a thing of the last thirty years. My father's family lived all over the Greater Lawrence area. It all seems like it was, back in the day, one big integrated area, even into the late 1970s and in my own early memory.

0 Comments

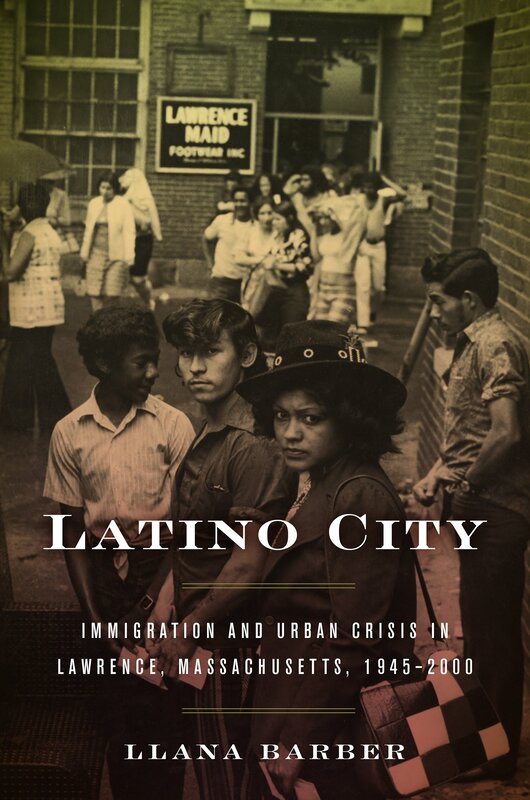

Ms. Llana Barber has written the first academic book about Lawrence's postwar transition, from declining milltown to outer-suburban Latino-majority hub. This is a very important book in understanding the recent history and potential future of Lawrence. She has all the pieces needed to tell the story:

She also has some interesting details about recent events that might interest locals. For example:

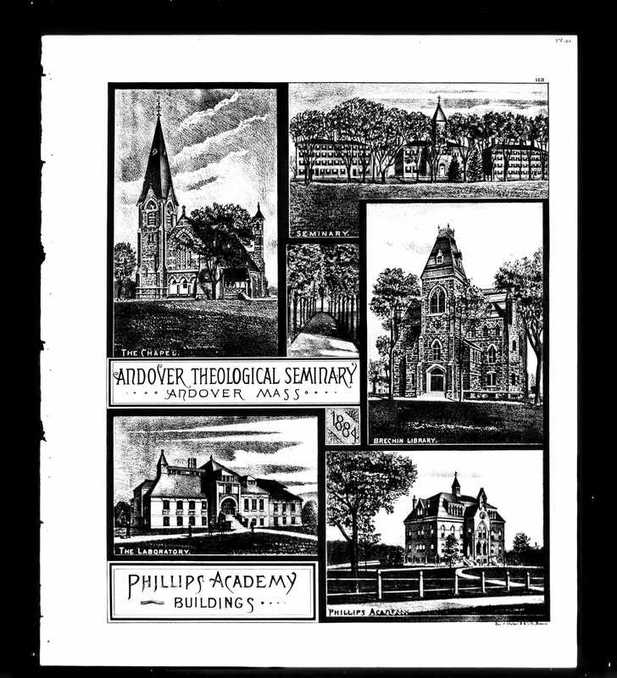

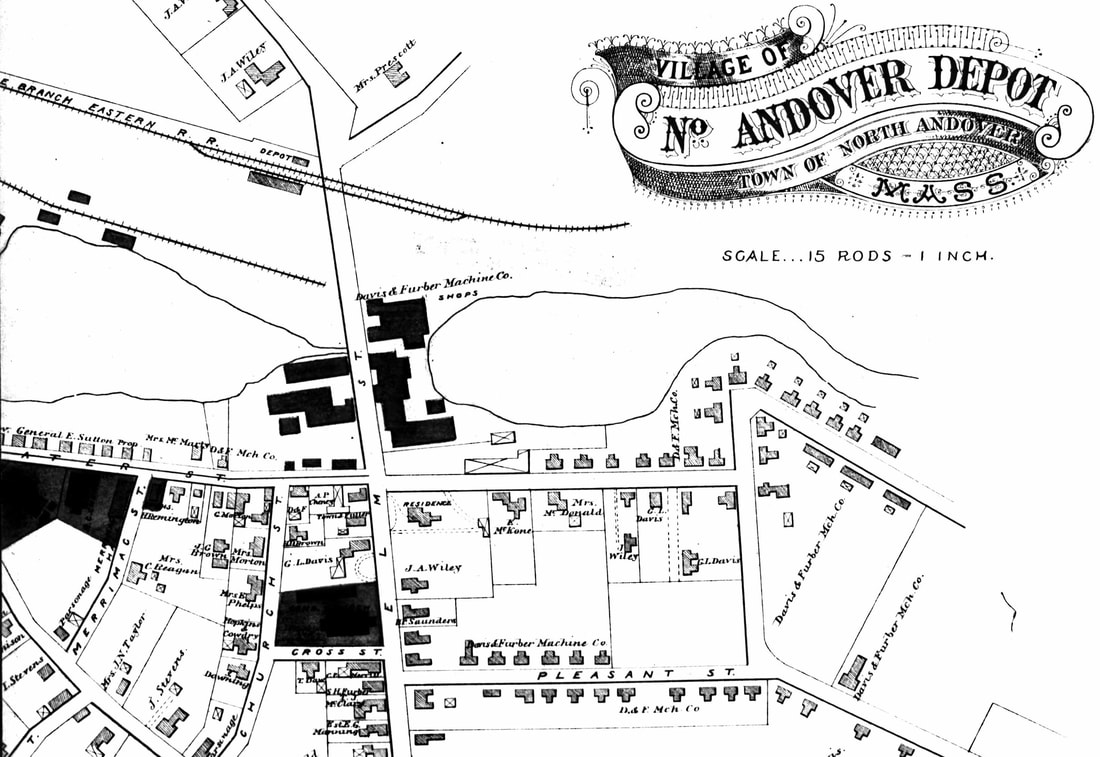

Anyone who is interested in the recent history of Lawrence, or the significance of a sizable Latino-majority city, should read this book. Background of Latino immigration and economic change She comprehensively tells the story of Puerto Rican and Dominican migration to Lawrence starting in the late 1960s. Prior to 1980 or so, most Latino immigrants were Puerto Ricans from New York who were attracted by the perceived safety of Lawrence compared to their New York City neighborhoods, plus the availability of jobs in non-durable goods manufacturing, mainly shoes – Lawrence Maid, Jo-Gal, etc. “In 1970, 83 percent of Lawrence’s employed Latinos worked in manufacturing, compared with only 34 percent in New York City,” she says. Also, Lawrence was perceived as relatively immigrant friendly in light of its history. Industrial jobs, immigrant friendly jobs and relative safeness of Lawrence compared with places like the Bronx were what started Latino immigration to Lawrence. However, by the early 1980s, industrial jobs had largely disappeared and newcomers - this time as many Dominicans as Puerto Ricans - were more attracted by the existing sizable Hispanic population. Her Analysis of the 1984 Riot I actually came across her book while checking my research on the 1984 Lawrence Riot. She has the first published analysis of the riot by an academic that I can find. (There was an unpublished Master's thesis, which is available at the Resources page.) She has an in depth description of the events of August 1984. In my view, the riot was not a very big disturbance, albeit one that local police could not get under control on the first night. It happened less than half a mile from my house with no immediate impact beyond a narrow zone running between Broadway and Margin Street along the base of Tower Hill, across an area of probably less than ten acres. I have suggested that it was more like a large-scale rumble, and not a "riot" in the same sense as the gigantic Detroit riots or Watts Riots which ranged over hundreds of acres destroying a lot of those cities. Even locally, compare the 1964 Hampton Beach riot, which involved up to 10,000 youth battling state police from New Hampshire and Maine and many neighboring towns. She has some interesting little details that I had not heard before: “At 11:00 PM rioters broke into Pettoruto’s liquor store. The Eagle-Tribune reported that at first the two groups [presumably whites and hispanics] fought over the liquor, but then they cooperated to divided it up and share it, after which a ‘lull followed with a lot of public drinking.” She notes dryly, “This odd reprieve could not have been long lived, because by 12:15 AM, the liquor store was on fire.” She also has a graphic description of police action on the second night. “At 10:30 that night, the head of the Northeast Middlesex County [i.e. Lowell area] Tactical Police Force ‘arrived to find Lawrence police pinned down – lying on the ground to avoid gunshots, rocks, bottles and Molotov cocktails.’ An early contingent of forty Lawrence police officers and the regional SWAT team had been no match for the hundreds of rioters who claimed the streets. By 12:30, however, the reinforced police from the surrounding towns and state police from six barracks, marched in cadence down the streets, pushing the Latino rioters in front of them, herding them into the Merrimack Courts (Essex Street) projects, where virtually very newspaper account assumed all the Latino rioters lived.” “Latinos lived throughout the neighborhood, however, and it is highly unlikely that all the Latinos at the riot site lived in the Essex Street projects.” She does point out that “it seems that many more white rioters were arrested than Latinos on the second night,” and that at least a handful of them were from neighboring towns who had come into Lawrence to get in on the action. She also has a very interesting reference to an editorial by Eugene Declercq in the Lawrence Eagle-Tribune (soon to be just the Eagle-Tribune, based in North Andover). “Declercq was one of very few commentators to take a metropolitan view of the riots, one that drew attention to the reality of the region's political economy. He challenged the suburban exemption from responsibility for the region’s poor, an exemption premised on politics of local control that enabled people living in the suburbs to exclude low-income residents as a way of protecting their property values and public services. ‘The cherished property values of the wealthy communities that surround Lawrence are secure because of a system that isolates its poor in cities like mine.’” He added “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free – but make sure they live in Lawrence and not near us.” Quibbles with the Book My biggest quibble is that she often falls back on a stark suburban-urban dichotomy to tell the tale of Lawrence versus its neighbors. While it is true that suburbanization (the building of federally funded highways, Freddie Mac financed suburban subdivisions and automobile infrastructure) led to the decline of Lawrence and other small cities in many ways, it does not follow that Lawrence's suburbs were somehow just Levittowns of single family homes built on farmland and shopping centers, and that Lawrence was just a teeming pit of abandoned factories and squalid tenements. As I tried to suggest in my blog entry about the separation of North Andover from Andover, there were industrialized, higher density areas of Lawrence's neighbors that blended almost seamlessly into abutting Lawrence areas. When I was a young child, my grandparents lived on Harold Street in North Andover in a duplex, on a street that almost entirely mirrored my street in Lawrence, Saunders Street, in terms of housing stock and residential demographics. And in the section of north Lawrence near where I later grew up, the neighborhood blended seamlessly into the abutting parts of Methuen. (The construction of Interstate 495 in the early-1970s probably exacerbated the distinction, as it cuts North Andover off from the Lawrence side of the former neighborhood, and provides a very clear frontier area between Lawrence and Andover). Although she tries to emphasize the urban-suburban dichotomy by regularly comparing Lawrence to Andover, this is somewhat misleading, as Andover was the most rural of Lawrence's suburbs and therefore in the best position for postwar greenfield suburban housing developments, especially because of the fortuitous location of highways and an existing commuter train station into Boston. Because of North Andover's industrial heritage, in contrast, it still had huge manufacturing employers into the 1990s. She does talk about the numerous Hispanics who lived in Lawrence and worked at Western Electric in North Andover in the 1970s and 1980s, thus undercutting her simple urban-suburban narrative. My own theory, which I suggested in my post on the August 1984 Lawrence Riot, was that the increasing dichotomy between Lawrence and its immediate neighbors was exacerbated by the 1982 desegregation of schools in Lawrence's peripheral "nice" neighborhoods. It had the effect of pushing existing residents of those neighborhoods over town lines and destroying the previous integration of those neighborhoods with the abutting neighborhoods of Lawrence's suburbs. She does describe with a lot of good detail how it is impossible to mandate desegregation or mixing of students across town lines. "Thanks to Milikken [a court case], the suburbs were not compelled to participate in any meaningful metropolitan desegregation plan, and none of Lawrence’s suburbs chose to participate voluntarily in such a plan with their nearest urban neighbor. An effort to create a voluntary ‘collaborative school’ in the late 1980s for students from Andover and Lawrence failed after it encountered intense opposition from Andover residents." The project would have been jointly run (and largely state-funded) elementary school designed to admit students from both municipalities. However, except for a passing reference to an early-eighties desegregation plan in Lawrence that "was on the verge of being implemented," she does not talk about the actually internal Lawrence desegregation process and its effects. Her analysis of the flaws of the former alderman system of government in Lawrence is well-done. This governmental structure persisted into the 1990s. "“Most critics focused on Lawrence’s alderman style of city governance. Unlike most cities, Lawrence had no professional administrators to head police, fire, street, or other departments." Its patronage based system meant an overwhelming exclusion of Latinos from city employment, although a voluntary quota system was implemented, targeting 16% in 1977 and going up from there. However, I would argue that the alderman system also had a structural benefit. It led to the existence of "crown jewel" neighborhoods in Lawrence, where most to the resources were concentrated and most of the voters lived who then benefited from patronage jobs. These neighborhoods were the upper part of Tower Hill, of Prospect Hill and Mount Vernon. Between the removal of the alderman system of government and internal desegregation, the crown jewel neighborhoods of Lawrence were basically equalized downward to the level of their poorer, less resourced neighborhoods in the flatlands. Thus, Lawrence lost a significant tax base [something that Barber continuously laments along with Lawrence's increasing dependence on state aid]. As a result of these forces, Lawrence's neighborhoods that previously could compete with similar neighborhoods in North Andover and Methuen were slowly turned into ghettos, starkly cut off from historically similar neighborhoods next door in neighboring towns. The fact that such crown jewel neighborhoods were mainly white (remember that until Hispanic migration, Lawrence was 95% white) misses the point. The point is that these neighborhoods were also of a different socioeconomic status and probably could have been a first stepping point up the socioeconomic ladder for recent Hispanic immigrants. Instead, as a result of the trends I just described, Lawrence effectively became one big self-contained Hispanic ghetto starting in the early 1990s, increasingly bifurcated from its historic neighbors. Conclusion Yet...maybe my quibbles with the emphasis of the story are wrong. Yes, Lawrence effectively became its own little Hispanic ghetto for a couple decades (I am using the term ghetto in the classic sense, as a place separated and walled off where a minority group is enclosed, such as the original ghettos for Jews in medieval Europe). However, Lawrence is arguably now turning a corner, as a completely Hispanic city. As Barber says “In a most basic sense, Latinos saved a dying city.” I agree. (A Long Read) Above: the South Parish Church, Andover, Massachusetts. The current church is the fourth meetinghouse built on the site. Photo by the author. Around the year 1800, a battle began over culture and tradition in the old town of Andover, setting the northern part of the town against the southern part. On the northern side was progressive, liberal enlightenment thinking that came to dominate the more educated classes of eastern Massachusetts in the nineteenth century; on the southern side were old New England traditions that were in danger of being lost. The split was arguably hastened by the much more significant industrialization of the North Parish by the 1840s, with large mills clustered around Cochichewick Brook and a growing area of worker housing, Machine Shop Village adjacent to newly-formed Lawrence; versus the less-industrialized South Parish. In many ways the conflict found in this one town, Andover, encapsulated the competing cultural trends of the first half of the nineteenth century of Massachusetts: Enlightenment versus Puritan; Urban versus Rural. These days, most people seem to be unaware of the somewhat tortured history that led to the separation of North Andover, which is actually the oldest part of the town, from Andover. Brief history of Andover’s parishes The town of Andover was founded in the early 1640s at the tail end of the original Puritan settlement that accompanied the Great Migration. See the Glossary. For many decades after original settlement, the town of Andover stood along the north-western frontier of settlement in Massachusetts, along with its then-near-twin on the northern bank of the Merrimack River, Haverhill. A few miles beyond the northern bank of the Merrimack was wild, forested country inhabited only by native Americans. The first settlement in Andover occurred at the present-day North Andover common, the oldest part of then-Andover. In addition to establishing a meetinghouse and hiring a minister from Harvard – the source of virtually all puritan ministers – a schoolmaster was appointed to teach reading, writing and arithmetic (required by Massachusetts law from 1642 onward). A common was laid out and house lots were provided nearby for convenience and for mutual protection against potential Indian raids. Farm lands were allocated to residents on the periphery of the town. After the original settlement, few houses were built on the common and all further residences were built closer to allocated farmland. Despite the original settlement of Andover in the 1640s near Cochichewick Brook, the population continuously shifted southward. In 1697, upon the death of Andover's second minister, the town agreed in principle to build another meetinghouse that was more convenient to more of the population. After a decade of dispute over proper location, the General Court of Massachusetts became involved, and a "South Parish" was "set off", meaning that, henceforth, residents in the larger, southern part of the town would be assessed separately in support of their own minister and meetinghouse. That first South Parish church was erected slightly to the east of the present-day South Church, while the North Parish built its own new meetinghouse on basically the same location as the previous North Parish meetinghouse. The two Andover parishes then co-existed uneventfully for a century. Such "setting off" was the ordinary course of things. The town of Haverhill, which at that time was enormous compared to Andover, had set off three additional meetinghouses and parishes by 1744 while remaining one town (with the exception of the creation of Methuen in 1725). Despite a history of harmony, however, starting around 1800, a number of social and economic currents ultimately drove the two Andover parishes apart, into near diametric opposition. After half a century of estrangement, they finally divorced in 1855, with the South Parish (plus its recent offshoot the West Parish) taking the name of Andover in exchange for a $500 payment; and the North Parish becoming the town of North Andover. Here is the story of that break-up. New England Congregationalism in the Age of Enlightenment The period following the American Revolution (and arguably all of the eighteenth century) was the Age of Enlightenment. Prominent thinkers, from Voltaire and Montesquieu in France, to David Hume and Adam Smith in Scotland, had shaped the Western intellectual landscape that hitherto had been dominated by theologians. Mankind grew confident in its ability to shape its own destiny, through rational thought and technology. According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “the expectation of the age [was] that philosophy – in the broad sense of the term, which includes the natural and social sciences – would dramatically improve human life.” In New England, Enlightenment thinking shone through the prism of the American Revolution. “Eighteenth century Rationalism under the influence of English philosophers like John Locke became the basis for new religious thought in the same way it had helped free America’s spirit of political independence. Locke defended individual liberty and equality and defended human rights. By 1805, Arminians had revamped Christian theology to conform with the principles of the Age of Rationalism.” From And Firm Thine Ancient Vow: The History Of North Parish Church of North Andover, 1645-1974, by Juliet Haines Mofford (1974). Who were these “Arminians”? In the context of the established congregationalist churches of Massachusetts, these were ministers and their followers who had rejected the harsh predestination of their puritan forbears, as taught by reformation leader John Calvin (hence Calvinism or Calvinist). Instead, they espoused the views of Jacobus Arminius. He was a Dutch reformation leader who had opposed the views of Calvin. We are not chosen to believe, he said (contrary to the Calvinist notion of “the elect”), but instead, all humans are given the power to believe in order then to be chosen by God *if* they chose to believe. Christ furthermore died to save all people, not just the elect, and in fact may not have been divine. (This led to the label “Unitarian” from critics, who wanted to uphold the Trinity of the godhead, Father, Son and Holy Spirit.) Some commentators viewed this shift as a natural consequence of the American revolution. “Most Arminian ministers were staunch Federalists and strong supporters of the politics of Washington and John Adams. Many ministers saw in Washington a symbol of national unity possible under the hand of God’s providence and guidance, and they said so in sermons.” (Again, quoting Moffard.) The Unitarians Begin to Dominate “The thoughtful men who represented the Liberals…were few in number at first and with few exceptions lived under the shadow of Beacon Hill or nearby.” (meaning they were your typical Boston rich liberal elites, I guess) (quoting The History of the Andover Theological Seminary, by Henry K. Rowe (1933)). However, by 1800, Boston’s Congregationalist churches had gone solidly Unitarian, with only two out of fourteen maintaining traditional Calvinist ministers. This led to the formation of Park Avenue Congregationalist Church, so-called Brimstone Corner, which reverberated with Calvinistic sermons about the utter depravity and damnation of man. The thunderbolt for the traditionalists, however, was the fall of Harvard to the Unitarians. Prior to 1800, Harvard college was essentially a training ground for all Massachusetts ministers. All students were a classical education deeply focused on reading of original texts in Greek, Latin, Hebrew and Aramaic, regardless of whether they went on to become ministers. The times they were a’ changing, however. “The tendency of the period was to introduce other studies in place of the older discipline, as science and modern literature became more popular in learned circles than Hebrew and Greek.” In short, in higher education, “Theology lost its position as queen of the sciences.” So, “when Reverend Henry Ware of Hingham was elected to the Hollis professorship of divinity at Harvard College in 1805, New England Congregationalism felt the shock, for it was well understood that Ware was really a Unitarian, and that at Cambridge his influence would be radical.” (All quoting Rowe). The Merrimack Valley is the epicenter of the Calvinist response – Andover and Newbury factions The strongest responses anywhere in Massachusetts to the fall of Harvard to the Unitarians seem to have come from Calvinist luminaries in Andover and in Newbury. “Dr. Eliphalet Pearson was disturbed gravely by the liberal trend at Harvard. Pearson was one of the outstanding men of the time in educational circles. He had been the first principal of Phillips Academy and had established its reputation, and after eight years he had been elected to a professorship at Harvard.” (Quoting Rowe.) Phillips Academy, located on a hill in Andover’s South Parish and chartered 1778, was in many ways just another typical “academy” found across that region at that time: a secondary school focused on advanced education for older boys, and sometimes girls, in order to further train them beyond the Three Rs of the schoolhouse –and, in the case of boys, prepare them for the rigors of Harvard. Governor Dummer’s Academy in the Byfield section of Newbury was the precedent for all of these academies of the lower Merrimack Valley, being the alma mater of Samuel Phillips, founder of Phillips Academy. Other similar academies could be found in Groton (now called Lawrence Academy, which for decades also educated girls), Haverhill (the “Haverhill Academy”, the first academy to accept girls, merged with Haverhill High School in 1841), and even in the North Parish of Andover (“Franklin Academy” which closed around 1845 – more on that below). However, from the early days, Phillips Academy did apparently stand out in terms of its academic rigor. “When [Pearson] failed to stem the tide of liberalism [at Harvard] in 1805, and then when Professor Webber was chosen president the next year, Pearson resigned his office and went back to Andover, convinced that something needed to be done to defend orthodoxy. The Academy, of which he was a trustee, cordially welcomed his return and gave him a year's rental of a new house nearby. Then he began to plan for the establishment of a theological institution which should maintain the doctrines of the fathers of New England against the threatening apostasies of the times.” (Quoting Rowe) Meanwhile, downriver in Newburyport, similarly minded leaders were meeting. Technically they were “Hopkinsonians” with slightly less Calvanistic views than Pearson and his cohorts on Andover hill. “Their leader was Dr. Samuel Spring, minister at Newburyport. He had been a pupil of both Hopkins and Bellamy, and had been a recognized leader in eastern Massachusetts for forty years. Leonard Woods, a young minister at West Newbury, was his close friend. Through Spring and Woods three laymen were aroused to an interest in theological education. These were William Bartlet [one t], a successful merchant of Newburyport, Moses Brown of the same town, and John Norris of Salem. They were all men of wealth, and though not all church members they were willing to use their money for religious purposes, and they soon agreed to support the plans for a theological school at West Newbury.” Why was the orthodox response to the Unitarians focused in the lower Merrimack Valley? My theory is that the region had the goldilocks location of not-too-much, not-too-little: on the one hand, it was still part of the original Puritan heartland settled by the Great Migration, and therefore of enough significance to have cultural sway over much of New England, unlike the frontier areas of New Hampshire and western Massachusetts that were still being cleared; yet, on the other hand, it was peripheral enough not to have fallen completely under the cosmopolitan influence of turn-of-the-nineteenth-century Boston, which was increasingly becoming a global port through which flowed the wealth of international trade via world-renowned Yankee merchant ships. Below: Andover Theological Seminary 1884 Founding of the Andover Theological Seminary After significant negotiation, the Pearson wing and the Woods wing agreed to form a theological seminary in Andover next to the site of Phillips Academy, sharing the same Board of Trustees as the academy. Because the two factions could not agree on the wording of their creeds, there were two sets of founding documents for the Andover Theological Seminary, one for the orthodox Calvinists and one for the Hopkinsonians. They were however unified in their antipathy toward Unitarians. On the orthodox side, it was provided that every professor must at the time of his inauguration solemnly promise to maintain and inculcate the Christian faith as summarily expressed in the Shorter Catechism [a standard statement of belief of early puritans] "in opposition not only to Atheists and Infidels, but to Jews, Mahommetans [i.e. Muslims], Arians, Pelagians, Antinomians, Arminians, Socinians, Unitarians, and Universalists, and to all other heresies and errors, ancient or modern, which may be opposed to the Gospel of Christ, or hazardous to the souls of men." Furthermore, every professor must repeat this declaration in the presence of the Trustees once in five years. Getting the Hopkinsonians on board was important because of the wealth they brought. The main building was named Bartlet Hall in gratitude for the gift of their main benefactor (it exists today on the campus of Phillips Academy and has been renamed Pearson Hall). The Hopkinsonians were thus allowed to have Associate Statutes that existed alongside the institution’s charter documents, and every occupant of a chair endowed by the Hopkinsonians “should be a Hopkinsonian.” “The establishment of the Seminary was a significant event in American church history. The union of the two theological groups of conservatives in the Seminary proved an effective counterpoise to the Unitarian trend in Congregational circles. Naturally the Liberals were not pleased. The Harvard attitude was not friendly. Woods reported to Farrar in 1807 that there was ‘loud murmuring and reproach and imprecation.’” (Rowe) “ANDOVER [Theological Seminary] was founded for the distinct purpose of preparing men for the parish ministry. At that time the prestige of the Trinitarian Congregationalists was at stake. The Unitarians had the advantage of Harvard instruction and the Harvard reputation. Unless the Trinitarians could establish a theological school that would attract young men of ability, and year after year could supply the Congregational churches with orthodox leaders who were able to measure swords successfully in doctrinal controversy when need arose, they would be worsted in the competition of the two theological parties.” It should be noted that, “in a legal sense the new Seminary at Andover was the theological institution in Phillips Academy, but it was so distinct in faculty, buildings, and funds as to be actually a separate school.” (Rowe) “It soon eclipsed Phillips Academy in endowment, buildings, and reputation. A few years after its founding, it included two large brick dormitories--the present Foxcroft and Bartlet Halls—with a chapel and recitation building...In addition, a number of homes had been constructed for the Seminary professors, the most im pressive being the present Phelps, Pease, and Stuart houses. By contrast, Phillips Academy had one wooden classroom building and a modest house for its principal.” (From Youth from Every Quarter: A Bicentennial History of Phillips Academy, Andover by Frederick S. Allis, Jr. (1979)) In sum, the essential institution for defending orthodox congregationalism was founded on a hilltop in the southern part of Andover, which some in the North Parish of Andover then called “Brimstone Hill.” The Seminary – the first school in America for training ministers that was not part of a college – was technically in the South Parish, but had its own independent congregationalist church. The Seminary exercised significant sway over the philosophy of the nearby South Parish church, and then the West Parish church, which was set off from the South Parish in 1824. Both were avowedly Trinitarian (and thus, at the time, Anti-Unitarian). They are still Trinitarian, to the extent such distinctions are relevant in modern society. Meanwhile, the North Parish of Andover was going in a very different direction As you might have guessed, the members of the North Parish generally considered themselves more forward thinking and enlightened. The South Parish handbook of 1859 went out of its way to label an early North Parish minister, Reverend William Symmes, who was ordained in 1758 and died in 1808, as an “Arminian” although such label is debatable. Another historian of the region, Sarah Loring Bailey in her 1880 history of Andover, called Symmes “the last of the old-time ministers.” It is definitely true that when a new minister was sought for Andover’s North Parish in 1809, being too Calvinist led to a rejection. “When, after the death of Dr. Symmes, the parish came together to ordain the minister whom they had called, the Rev. Samuel Gay, it proved that the views of Christian doctrine which he expressed were not satisfactory to all the officers of the church and parish, being more rigidly Calvinistic than they approved. The ordination services were, therefore, broken off.” (Quoting Bailey) Instead, they hired Reverend Bailey Loring who was ordained on September 19, 1810, age twenty-three. Interestingly, he was a graduate not of Harvard but of Brown. Of the four colonial era colleges in New England, Brown was an outlier in that, from its inception, it allowed different religious views (although, having been founded by Baptists expelled from Massachusetts, it was required until 1950 to have a Baptist minister as its president). In my research of the various meetinghouses of the lower Merrimack Valley going back to the 1630s, I have never come across a minister educated at Brown, although two were educated at Yale and one at Dartmouth (other congregationalist stalwarts). Dozens if not hundreds of ministers in Massachusetts prior to 1800 were educated to Harvard. “Mr. Loring was not a Calvinist. His theological education had been under the Arminian school of belief. But, like his predecessors, he was catholic [meaning universal not Roman Catholic] in his sympathies, and maintained throughout his ministry friendly relations with his brethren of various creeds. He continued to exchange pulpits with those of similar tolerant principles, even after the partition walls had been built up between the two divisions of the Congregational order, and when this breaking through was censured by the more dogmatic of both parties.” (Quoting Bailey) He did, however, establish a new covenant between members, one of distinctly Unitarian beliefs. Some supporters of the North Parish side of the story saw a conspiracy against him coming out of the Seminary and the South Parish. Ms. Moffard notes in her 1974 history of the North Parish church that Loring was rejected from the Andover Seminary for incompatible beliefs, and this fact “weighed in Mr. Loring’s favor” when he was ordained by the North Parish. “Bailey Loring was their man, an unmistakable and irrepressible Arminian who was undaunted by the proximity of the new seminary in South Parish.” (quoting Moffard) “The schism began, possibly as early as 1820, when certain members felt that Mr. Loring and North Parish were not satisfying their soul yearnings…they held the belief, not only in Jesus of Bethlehem, a historical teacher [the classic Unitarian view which, by the way, in my book is no longer Christian per se], but in Jesus the Christ, Lord and Savior…Students from the Seminary were often present to lead them in worship.” (Moffard) Eventually, a Trinitarian faction was able to form in North Parish, apparently aided by the Theological Seminary. Their situation was greatly aided by the 1833 disestablishment of the Congregational churches in Massachusetts, which meant that, henceforth, financial support could not come from the parish poll tax; rather, churches had to be dependent on their members, who could live wherever they wanted. On July 24, 1834, the Trinitarian Calvinistic Church was formally organized. On September 3, 1834 the new building was declared. It could be viewed as a mission church from the South Parish: of its members, only one male member was a defector from the North Parish, while 14 came up from the South Parish. This church changed its name to Trinitarian Congregational Church in 1841, and bears that name to this day. The Unitarians in North Parish engaged in no such missionizing, and for the entire 19th century, Andover’s South and West Parishes had no Unitarian church, presumably being under the sway of the Theological Seminary. The existing Unitarian-Universalist church in Andover moved there from Lawrence in 1964. Below: Interior of North Andover’s Trinitarian Congregational Church, built 1865 by the same architect as the 1861 Andover South Parish Church (source: church website) The Cultural Differences Between North Parish and South Parish Illustrated by a Comparison of Academies Pages could be written about the strict, cold demeanor of Phillips Academy and the Andover Theological Seminary. The following gives a flavor of life as a student at the Theological Seminary. Life at the Academy was not that much different apparently. “For exercise the students blasted and cleared away rocks from the Missionary Field back of the buildings, worked on the campus grounds, and rambled about the vicinity. Two students, one of whom became a well-known college professor, used to race each other around a three-mile triangle on winter mornings before sunrise to give tone to breakfast and the day's work. Professor Park, when a student at Andover, arose at 4.30 and walked with another student over Indian Ridge or through Carlton's Woods, practising elocutionary exercises in order to develop his oratorical powers.” (Rowe) The author notes rather dryly “The students do not seem to have been miserable, perhaps because they were seldom idle.” Here is a letter from one Andover student in 1819: “That you may know how much a slave a man may be at Andover, if he will follow the rules adopted by the majority, I will give the order of the day. By rising at the six o'clock bell he will hardly find time to set his room in order, and attend to his private devotions, before the bell at seven calls him to prayer in the chapel. From the chapel he must go immediately to the hall and by the time breakfast is ended, it is eight o'clock, when study hours commence and continue till twelve. Study hours again from half past one to three. Then recitation, prayer, and supper, makes it six in the afternoon. Study hours again from seven to nine leave just time enough for evening devotion before sleep.” Meanwhile, the North Parish had its own academy, the so-called Franklin Academy. It can hardly be more different than Phillips Academy, yet in its heyday it seems to have attracted students from as far and wide as Phillips Academy. “In 1799, Mr. Jonathan Stevens gave land on the hill north of the [North] meeting-house. Subscriptions were made by some of the principal citizens. The academy also received a fund of a little more than eight hundred and seventy-five dollars from the division of the proprietors' money [each of Andover and Haverhill and successor towns such as Methuen had rights obtained from the original settlers, the so-called Proprietors, who had paid money for the deeds from the Indians; by the eighteenth century, it was a separate fund that was slowly depleted as the last of the proprietor land was sold off]. The academy was built in 1799. It had been provided that the school should be for both sexes, and it was the first incorporated academy in the State where girls were admitted. The academy was built with two rooms of equal size, — the north room for the male department, the south room for the female department. A preceptor and preceptress had charge respectively of the two departments.” “The school was incorporated in 1801 as the North Parish Free School, and in 1803, by act of the General Court, the name was changed to Franklin Academy. This school, though now discontinued, had a flourishing life of more than fifty years, and numbered among its members students from more than a hundred different towns, a dozen States, and several foreign countries…”(in other words, on par with Phillips Academy of the time.) “Two manuscript records have been found, one containing the names of the male students from 1800 to 1802, and from 1811 to 1834, the other the names of the female students from 1801 to 1821. The names of the preceptors are nowhere found recorded, and the recollections of the pupils and residents of the town in regard to them are indistinct and often conflicting. The following are such facts as the means of information supply: The first Preceptor was Mr. [presumably the Rev. Micah] Stone, of Reading, a graduate of Harvard College 1790, tutor 1796, student of theology with Rev, Jonathan French, Andover, settled 1801 at Brookfield. Mr. James Flint (Rev. Dr. Flint, of Salem) was Preceptor, 1800-1811.” The student experience at Franklin Academy contrasts markedly with the Calvinistic south parish and Phillips Academy: “The reminiscences of the few who yet remain of the early students of Franklin Academy, are of delightful days. The notions of propriety in the North Parish were then much relaxed from the rigidity of Puritan customs, and many social recreations were permitted to the young folks. These festivities the elders directed and shared.” The Franklin Academy ultimately went out of business, it was said, because North Parish – soon to be North Andover – started providing decent town-led secondary education in the form of a High School. This was also the fate of Haverhill Academy, another early academy. It is not surprising that in liberal North Parish, universal secondary education should become provided for by the town and not by private means. Below: North Andover Depot, 1884 showing Davis & Furber facilities on the Cochichewick Brook. Note the Trinitarian Congregational Church at Cross & Elm The Split The actual split into two towns did not happen until 1855, when the matter was put to a vote. South Parish paid North Parish $500 to use the name Andover, despite North Parish being the original part of Andover. By the time of the split, North Andover had become significantly industrial. Four significant industrial concerns clustered around Cochichewick Brook: North Andover Mills, Scholfield Mills, Sutton Mills and Davis and Furber Machine Company. This area of North Parish was in some ways an appendage of Lawrence. There was even discussion of the entire North Parish becoming part of Lawrence, then a booming industrial city full of promise and on the up-and-up (and in 1877 a small section did become part of Lawrence). It is indicative that, whereas the Machine Shop in North Andover was already connected to Lawrence by public street trolley in 1868, there wasn’t a trolley to Andover until the 1890s, the peak of trolley construction when trolleys ran to every neighboring town. (Source: Maurice Dorgan’s Concise History of Lawrence, 1918). “Though the south village of Andover remained unchanged, the industries of North Andover and the mills of Lawrence were so near that her citizens could not remain oblivious to the changes that were taking place. With a rapidly increasing population, New England was sending her sons to the West to be pioneers like their colonial ancestors, and home mission societies were organizing to take care of their religious needs. [See my review of Yankee Exodus.] The application of steam to railway and river travel facilitated the movement of the population, and people became less provincial as their contacts widened.” Supposedly, the split was led by members of the South Parish. They have wanted to keep their relatively rural, traditional idyll untainted by the newfangled ideas and newfangled megaindustry that typified the North Parish. A description of Andover Hill written in 1856 by a student reflects the desire to maintain the rural idyll despite the encroachment of industry and change: "To the north the eye can travel up to the blue hills of New Hampshire, and only three miles distant stand and smoke the mammoth factories of the city of Lawrence. The whole scenery about is dotted with sequestered villages and snow-white farmhouses. Lowell, Salem, Haverhill, and Boston, are next-door neighbors. On the south is a hedge of railroad; on the east we can almost hear the roaring of the ocean; on the north flows the devious but busy Merrimac; while the west, to say nothing of its home associations, gives us a never-to-be-forgotten sunset. Thus environed, overarched by a deep blue sky, and standing upon ground whose beauty pen and paper cannot paint, Andover is the spot for a seminary. . . . Nearly every house looks like a countryseat, and even the old edifices, which were raised, I suppose, in the last century, have an air of neatness about them, being clothed in the purest white. It is a very wealthy place; but the wealth of the Seminary astonishes me. Nearly every house within a quarter of a mile is owned by the Trustees." Legacy of the Andover Theological Seminary By 1908 when the Andover Theological Seminary departed from Brimstone Hill in south Andover for Cambridge, leaving Phillips Academy to fend for itself again, the world was completely different from when it was founded a century earlier. Both forms of congregationalist religion were dissipated, Unitarian and Trinitarian, as competing protestant denominations planted their roots in New England; and then as Boston elites started defect en masse to the Episcopalians, perhaps conflating their Yankee roots with Englishness and forgetting that the Anglican Church had been the scourge of the puritans. The Seminary itself suffered scorn and mockery in the Boston papers for engaging in a sort of theological purity test for Professors in the 1880s. Its heyday was the period from 1808 to the Civil War. When it merged into the Harvard Divinity School (ironically) it only had three students. Yet it left a gigantic legacy on the intellectual landscape of America, because of the tendency of traditional Congregationalists who migrated out of the puritan heartlands of New England (see my entry on the Yankee Exodus) to establish colleges…and their desire to have intellectually rigorous Andover Seminary men as presidents of those colleges. “It is impressive to call the roll of colleges that invited Andover [Seminary] men to be their presidents. In New England they include Bowdoin and Dartmouth, Middlebury and the University of Vermont in the northern tier of states; Amherst, Smith and Brown in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. In New York were Hamilton, Union, and Vassar. Five were in Ohio: Antioch, Marietta, Oberlin, Western Reserve, and Ohio Female College. Moving steadily westward one finds Andover alumni at Wabash, Indiana, Illinois and Knox in Illinois, Drury in Missouri, Washburn in Kansas, Colorado among the Rockies, and Pomona in California. In a more northerly latitude are Adrian and Olivet in Michigan, Beloit in Wisconsin, Iowa College in Iowa, and Fargo in North Dakota. Howard University in Washington, D. C, Atlanta in Georgia, Rollins in Florida, Fisk in Tennessee, and state colleges in Alabama and Tennessee, gave wide representation to Andover in the South. For good measure the universities of Wisconsin and Kansas should be added. And overseas were Robert College in Constantinople and the Syrian Protestant College at Beirut [later the American University of Beirut].” (quoting Rowe) North Parish Unitarian Church, North Andover, Mass. Photo Source: Wikipedia. Present structure erected 1834.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed