|

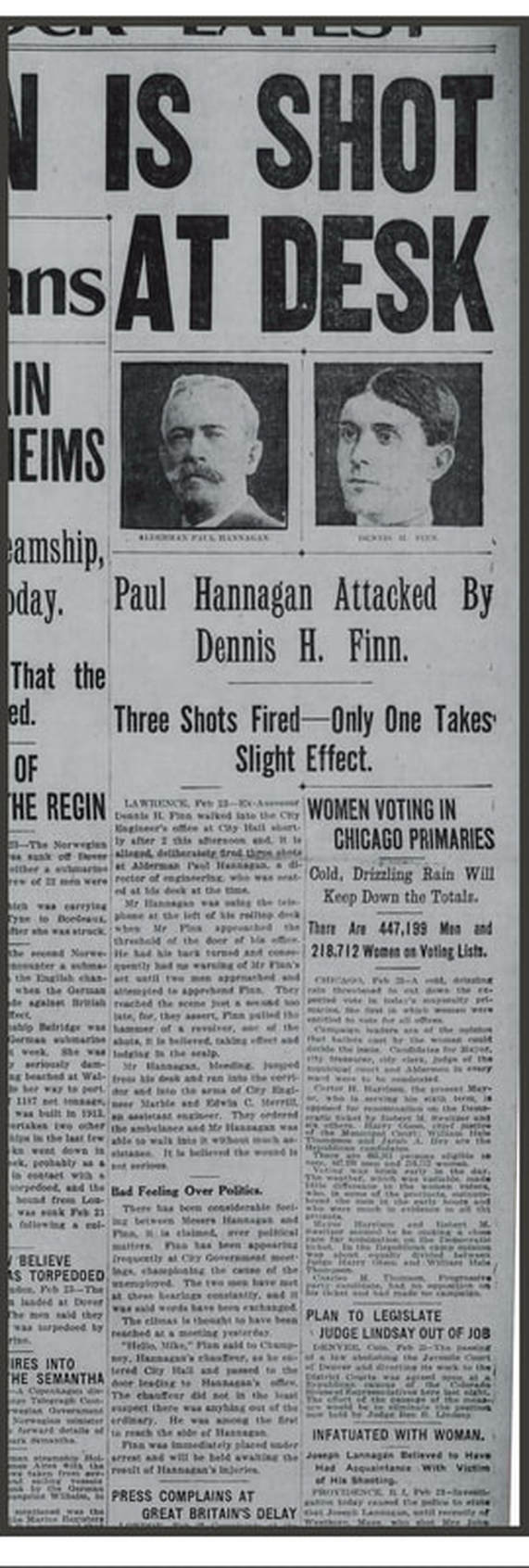

The Boston Globe reported on February 23, 1915, ex city assessor Dennis H. Finn fired three shots at Alderman Paul Hannigan, grazing his head. The reason given: "Bad Feeling Over Politics". Here is the article. Scroll to the bottom for a higher resolution pdf of the article, which is more legible.

0 Comments

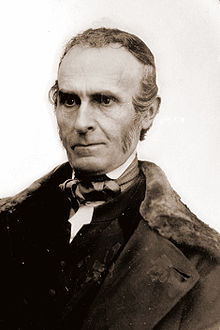

The Yankee Encounter with the Shanty Irish: Henry David Thoreau's Poem "I am the little Irish boy"3/24/2018 I am the little Irish boy That lives in the shanty I am four years old today And shall soon be one and twenty I shall grow up And be a great man And shovel all day As hard as I can Down in the deep cut Where the men live Who made the railroad. For supper I have some potato And sometimes some bread And then if it’s cold I go right to bed. I lie on some straw Under my father’s coat My mother does not cry And my father does not scold For I am a little Irish Boy And I’m four years old. Below: Henry David Thoreau (Source: Wikipedia) The above poem, classified as "doggrel" or a nonsense poem, was written by the famous American philosopher and writer Henry David Thoreau in Concord, Massachusetts in 1850. He wrote it at the height of the Irish refugee crisis, when improverished Irish refugees fleeing the Irish potato famine built refugee camps called shantytowns on marginal land. The newcomers mostly worked at menial pick-and-shovel jobs, building roads and railways. Thoreau kept prolific journals. Through them, we learn something about his encounters with his Irish neighbors living in the woods in a shack, just like he was (although he did so out of philosophical choice, they out of bare necessity). The boy’s name was Johnny Riordan. Thoreau first mentioned the boy in a journal entry of November 28, 1850, when he penned the poem. A few weeks later, on December 21, 1851, he became upset about the boy’s condition: “This little mass of humanity, this tender gobbet [?] for the fates, cast into a cold world with a torn lichen leaf wrapped about him…I shudder when I think of the fate of innocence.” On February 8, 1852 Thoreau finally acted. “Carried a new cloak to Johnny Riordan,” he remarked in his journal. Upon giving his gift to the boy, he gained entry to the Riordan shanty. He wrote in his journal, favorably if very condescendingly, that “the shanty was warmed by the simple social relations of the Irish…What if there is less fire on the hearth, if there is more in the heart!” Thoreau’s friend, philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson, who was also living in Concord and on whose wooded lands Thoreau lived, wrote to Thoreau: “Now the humanity of the town suffers with the poor Irish, who receive but sixty or even fifty cents, for working dark till dark, with a strain and a following-up that reminds me of negro-driving.” A few weeks later, Thoreau wrote back to Emerson positively: “The sturdy Irish arms that do the work are of more worth than oak or maple. Methinks I could look with equanimity upon a long street of Irish cabins and pigs and children reveling in the genial Concord dirt…” In this correspondence, as in his dealings with the Riordan family, Thoreau seems very sympathetic towards his poor Irish neighbors living in their shanties and laboring at building the railroad. And yet…Thoreau was at this very time putting the finishing touches on his masterwork, Walden. In it, he famously and derogatorily denigrates his shanty-Irish neighbor, John Field, for his “inherited Irish poverty” and lectures him for not being able to resist wanting “luxuries” like butter and tea that force him to slave and toil from dawn to dusk, instead of saving his pennies to better his situation. Even better, suggests Thoreau, Field should realize that he should transcend his material needs entirely! And all that coming from a Harvard-educated bachelor who can afford to live in the woods in a shack, not out of necessity but to make a philosophical statement! The poem “I am a little Irish boy”, then perhaps was not meant by Thoreau to be sympathetic, but rather sarcastic. Maybe it's making fun of the boy and the pathetic constraints on his life that have already predestined him to an existence of digging ditches. Nevertheless, the poem can be touching when read in the right spirit. I found this version of it, set to music and sung, that is particularly touching. I hope you enjoy it. PS: At some later point, I hope to write a blog post about Thoreau's journey on a raft down the Merrimack River with his brother, which he covered in his book "A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers" (the Concord River flows into the Merrimack at Lowell).

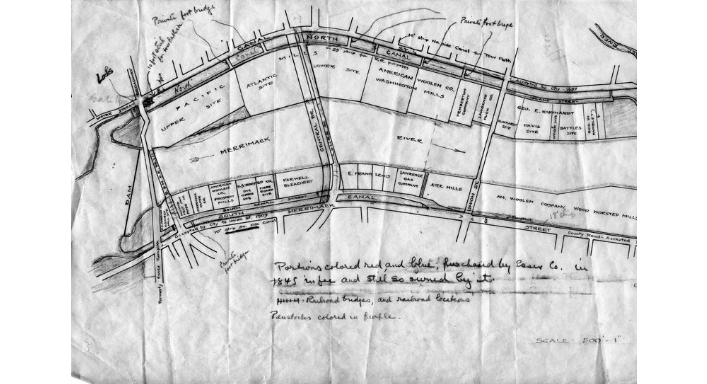

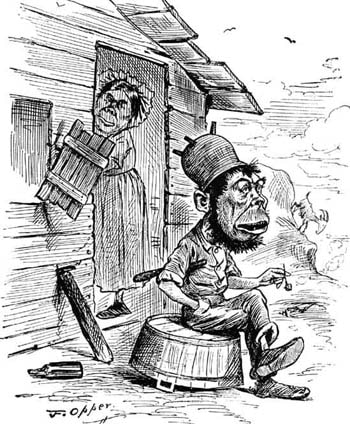

Above: Katherine O'Keefe O’Mahoney, born Ireland 1855, died Lawrence, Mass. 1918 (Source: Lawrence, Massachusetts by Ken Skulski, 1995) The Backstory Before there was Lawrence, there was ye olde New England: clapboard farmhouses, village greens, slow-moving farmers who mended their stone walls and carted their produce to market. This is how things were in 1845, the year Lawrence was founded as a town. Things in 1845 really weren’t all that different from 1645, two hundred years earlier, when the area was first settled by English Puritans in the towns of Andover and Haverhill. The ancient towns were later carved into the towns that we know today – Methuen, Salem N.H. (both formerly part of Haverhill), North Andover (the original part of Andover)…and Lawrence. Sure, the railroad had been introduced a decade earlier, and the Puritans had mellowed somewhat. People were no longer executed for witchcraft or whipped for heresy. But the culture was basically the same as it had been for generations. The original Puritan settlers had come forth and multiplied, cleared the land, built meetinghouses. Some of them went off to sea, chasing whale oil or Far-East silks and spices; or enterprisingly built waterwheels to grind their neighbors’ grain. Some of the local militia boys had gone off to the Battle of Bunker Hill and other early encounters of the Revolution. Basically, however, people farmed, traded, read their King James Bibles, attended meetinghouse, lived and died. Things were homogeneous and consistent, generation after generation. Below: Typical New England farm of the early 19th Century, similar to Bodwell's Farm in what became Lawrence (Source: New England Historical Society) Then, in the second half of the 1840s, two things happened: (1) industrialization and (2) a refugee crisis. Here Come the Factories The fast-moving tributaries of the Merrimack River had always powered waterwheels – little mills that were used to grind grain, saw logs into boards, or run a few looms to supplement the homespun cloth. However, in the 1840s, the mills being planned were different: they would now be on a grand scale. The immense new wealth of the spice trade and whaling was chasing new investments, and could finance endeavors on a previously unimaginable scale. The industrial revolution was underway in Britain and provided the technology. The planned textile city of Lowell was the first example, as we all know, but bigger and bigger factories could be planned. So a group of rich Boston merchant pooled their capital to form the Essex Company. In 1845 this company started to build Lawrence in a backcountry corner of Essex County, smack in the middle of farmers’ fields that had been cleared two centuries earlier. Their project – to build the largest dam in the world across the Merrimack and force its waters down two long canals to power dozens of enormous mills – required a lot of labor, the cheaper the better. Below: Plan for Lawrence showing new dam, canals and plots for water-powered textile mills, 1845 (Source Digital Public Library of America) Here Come the Irish Refugees And who should conveniently show up but a bunch of Irish refugees who could be put to work for pennies a day? These rag-clothed, impoverished, filthy bands of people were escaping the biggest humanitarian crisis of their time. The Irish Potato famine was so severe it killed one third of the people and forced another third to flee. The Famine Irish had arrived on dangerous, unseaworthy “coffin ships” operated by unscrupulous people-runners looking to exploit the desperation of the refugees. A risky voyage across the water was nevertheless preferable to staying in Ireland. Below: A So-Called Coffin Ship Leaving Queenstown (Now Cobh) Ireland, 1848 The Irish migrants crowded the port of Boston, then made their way inland, likely on foot, looking for work. The stream of refugees began in 1847 and did not abate until the mid-1850s. At Lawrence, they formed their refugee camp – the shantytown on the southern bank of the Merrimack – and the men started working on the dam. One of these laborers was my great great grandfather, Jeremiah Driscoll, arrived from Ireland in 1851 at age 29. He worked as a laborer for the Essex Company. His home address in the Lawrence town directory, once the town was big enough to have a directory, was “Shantytown, South Side.” Other Irish built a shantytown/refugee camp on the plains above Haverhill Street, near the Spicket River. A report from 1870 stated that some shanties had to be cleared for construction of the Lawrence reservoir. One of them was 120 feet long, and made of rough boards. It housed 80 people, mostly single men but also a family who built the place and charged the boarders a half penny a day to shelter there. Below: Derogatory Cartoon Depicting Shanty Irish Irish Pride in Early Lawrence Fast forward thirty-five years or so to 1882. Lawrence has grown from a couple hundred residents to 38,000…and around half of them are Irish. Although the town is seven square miles, most folks are concentrated in walking distance of the mills lining the river, spanned now by three bridges. There are by this time over a dozen large textile mills with more being built. The Irish, though largely still poor, have survived massive prejudice and exploitation within a largely hostile Yankee society. What do they do to show their pride? Do they march in a St. Patrick’s Day parade? Hardly – the first proper St. Patrick’s Day parade in Lawrence wasn’t until the 1900s. Go to a Riverdance concert? Listen to the Dropkick Murphy’s? No: they celebrated their Catholic faith by building magnificent churches and then organizing their lives around them. Below: Interior, St. Mary's Church, erected Lawrence, Mass. 1871

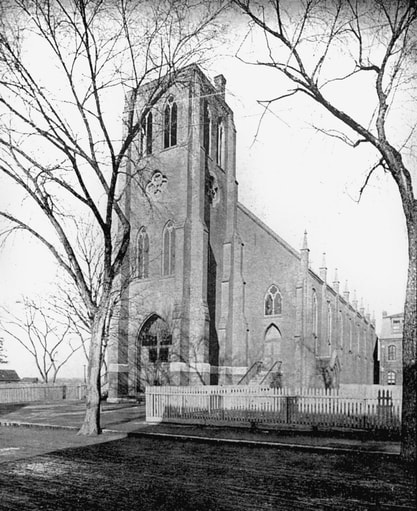

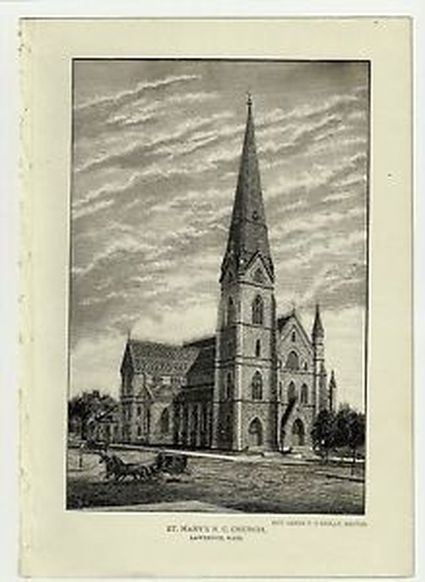

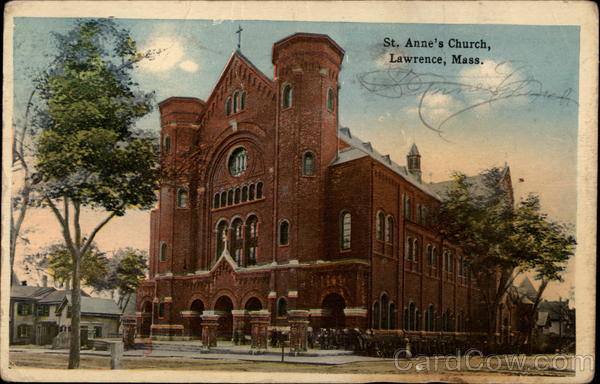

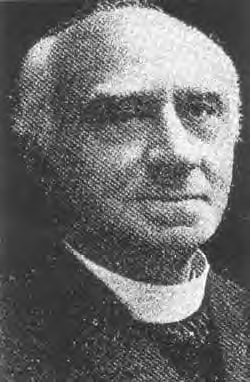

As one observer wrote, the Irish were known to spend their money on beautifying their houses of God before they beautified their own homes. Indeed, in 1882, three grand churches had been constructed of granite and brick in Lawrence – Immaculate Conception on Chestnut Street, St. Mary’s on Haverhill Street, and St. Lawrence O’Toole at the corner of Essex and Union Streets (it was renamed Holy Rosary in 1904 when the new St. Laurence O'Toole was built on East Haverhill Street). Yet at the same time, many Irish in Lawrence still lived in shanties. The last shanty was not torn down until 1894. Above: Immaculate Conception Church, Chestnut Street, Lawrence (Source: Queen City Blog). Lawrence's first permanent Catholic church, torn down 1991.The sense of Irish pride in their Church and its institutions – its grand churches, its rigorous schools, its charities like orphanages and hospitals – is captured in an 1882 book, “Catholicity in Lawrence” by Katherine O’Keefe O’Mahoney. According to Ken Skulski’s history of Lawrence, O'Keefe was “an author, lecturer and educator”. Irish-born, she graduated from Lawrence High School in 1873 (a rarity for girls, especially an immigrant girl), and then she started working there as a teacher. “Robert Frost considered her one of his favorite teachers. She was also among the first Irish-American women to lecture in New England. Her books include A Sketch of Catholicity in Lawrence and Vicinity (1882) and Famous Irishwomen (1907).” She also published a newspaper for Irish-American Catholics in Lawrence and conducted Irish classes there. She died at her Tower Hill home in 1918 at age sixty three. (Source: Ken Skulski’s Lawrence, Massachusetts.) For the about the first thirty year's of Lawrence's existence (until French Canadians started to arrive), pretty much the only Catholics in Lawrence were Irish. Reading O'Keefe's proud descriptions of St. Mary’s Church, you can get a sense of the importance of a magnificent church like this to the community:

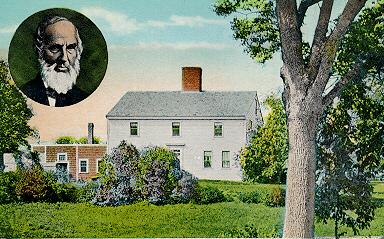

Below: St. Mary's Church, Lawrence, Mass. erected 1871 For her, the priests are towering figures, and funerals of priests are the equivalent of a funeral for a head of state. The following is from her description of the 1875 funeral of Father Louis Edge, O.S.A., who built St. Mary’s along with the Augustinian Order. She claims that 10,000 people viewed his body lying in state in his coffin in front of the altar. Note the participation of the numerous Irish social and religious organizations: “Early on Monday morning, crowds began to assemble in the vicinity of the church, awaiting the opening of the doors. The Ancient Order of Hibernians, numbering nearly 150 men, were the first to enter, and to them was assigned the East wing; after them came the Ladies’ Sodality of St. Mary’s Church, with medals and white veils. They numbered over seven hundred, and presented a beautiful appearance. The Irish Benevolent Society, headed by the Lawrence Brass Band, were the next to enter the church. They numbered nearly two hundred, and bore a silken mourning banner; they were seated in the Gospel aisle. Next came the Ladies’ Sodality of the Church of the Immaculate Conception, in white veils, similar to St. Mary’s Sodality; they had been assigned to them the West wing. After them came the Men’s Sodality of St. Mary’s Church, wearing white sashes and white crosses; they were placed in the Epistle aisle. And then came the Catholic Friends’ Society, and the Conference of St. Vincent de Paul. The church was tastefully draped in mourning, the black festoons in the galleries were relieved with white rosettes, and the mourning on the altar with small white crosses. Over the altar was a large cross, formed of blazing gas-jets; and there was a star of gas-jets [!] in front of the organ. When the clergy, forty-six in number, entered the sanctuary to chant the Solemn Office, the scene was truly grand and impressive.” She then goes to name each of the forty six priests in attendance, treating each one as a celebrity. “The architect of this magnificent structure was [Irish-born] P. C. Keely of Brooklyn, N. Y.,” she continues. He was in fact one of the preeminent architects of Catholic churches in the Northeast in the latter half of the nineteenth century. “The stone work was under the supervision of James Trainor of Boston; the wood work was superintended by James Bulger of Burlington, Vt; and the painting, as we have recently stated, was by Schumacher of Portland, Me. Its cost was over $200,000.” Given that this amount was largely raised by small donations from the commuity, it is quite an amazing sum considering that a laborer made a couple dollars a week. Later, she describes the fundraising campaign to pay for the bells of the church (weighing a total of over 10,000 lbs). The list of donors reads like a directory of Irish residents of Lawrence: John Kiley, Sr., Patrick Moran, John Brennan, Patrick Connors, Joseph Morrissey, James Kilbride, Anne O’Donnell, Mary Anne Quinn, Mary Connolly, Mary Burke, Bridget Bradley, Catherine Cushing, Thomas Regan, Mary Dowd, Mary O’Brien, Mary McCarthy, Rose Walsh, Mary Burns, Sarah McGuohan, Maria O’Sullivan, Annie M. Rafferty, Kate Reilly, Ann Mahon, Mary McGuinness, Rosanna Mulligan, Ellen McCavitt, Hannah Moriarty, Mary J. Sweeney, Ellen Ryan… The list extends for a couple hundred more names, three quarters of them obviously Irish in origin. Far more than half of them are women. Katherine O'Keefe O'Mahoney dedicated her life to promoting Irish pride. I have newspaper clippings of a lecture tour she did in 1911, about Ireland featuring numerous illustrations. She is billed as "a little woman with an enormous voice." Irish Legacy In the Catholic Church By focusing on their religion as a defining institution of being Irish, the Irish came to dominate the Catholic Church in America. “In 1880, the percentages of the clergy who were Irish American was 69 percent in the Archdiocese of Boston…Moreover, in 1886 thirty-five (51%) of the sixty-eight Catholic bishops in America were Irish born or of Irish descent. In 1920, it was still the case that two-thirds of Catholic bishops were Irish American, and in New England, that proportion was three-fourths.” (Source: American Catholics in the Protestant Imagination: Rethinking the Academic Study of Religion, by Michael P. Carroll, 2010) Later, when other Catholic immigrant groups followed - first the French Canadians, then the Poles, Italians, Portuguese, Lithuanians and (a few) Catholic Germans -- they found waiting for them a church that could provide something of a welcome, whereas the Irish basically had to create the Church in New England. Epilogue Since the early 1990s, many of the grand Catholic churches of the original Catholic communities of New England have been closed and often torn down. In Lawrence, this includes the aforementioned Immaculate Conception and St. Lawrence O'Toole, as well as half a dozen other churches. The same pattern was repeated in other urban centers: Lowell, Haverhill, Fall River, Worcester, Boston. I hope this and other blog posts will remind people that these abandoned churches were not just religious institutions, but were part of the physical culture of the immigrant groups who built them. Below: Today's St. Mary's church (Santa Maria de la Asunción)(source: church website) Below: John Greenleaf Whittier. Source: Wikipedia I'm supposed to do 52 profiles of ancestors in 2018 and I'm falling behind! So here is #8: John Greenleaf Whittier. He's a nearly forgotten poet who in his day was a household name. This was back before radio or TV, when people read (to themselves and to each other) for entertainment. John Greenleaf Whittier is not my ancestor. He can't be. He never had children. We are however, related...his great grandfather Joseph Whittier (1669-1717) of Haverhill is my eighth great grandfather. This makes us second cousins seven times removed. Say that ten times fast! Because he has been an important source for me in learning old stories of the area, I decided to include him in the 52 ancestors list. Below: John Greenleaf Whittier birthplace, Haverhill, Mass. (Source: Hampton N.H. Historical Society) Above: John Greenleaf Whittier Home and Museum, Amesbury, Mass., where he lived for over fifty years. Source: museum website So who was this guy, famous enough to have two historical museums in the area, one in Haverhill (where he was born) and one in Amesbury (where he lived when he was famous)? Basically, he was a self-educated farmer who lived in an ancient farmhouse in Haverhill - it was already well over a century old when he was born there in 1808 - that had been built by one of the founders of Haverhill. He wrote a lot of poetry, and was involved in the movement that wanted to abolish slavery in the United States. This activity got him into the circle of famous abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who was editor of a newspaper in Newburyport for a time. This newspaper started publishing Whittier's poems, and later when Garrison got more famous and began running in literary circles, he was able to promote Whittier. He became famous as a result of his poem Snowbound, about being snowed in. It starts like this: "The sun that brief December day Rose cheerless over hills of gray, And, darkly circled, gave at noon A sadder light than waning moon." Based on his literary fame for this and other poems, he eventually received an honorary degree from Harvard. Whittier himself barely left the area around Haverhill, other than a couple years in Philadelphia and New York when he was a young man. He complied lots of the historical stories of the Merrimack Valley area into poems. I have written blog posts about some of these topics, such as the story of Captain Waldron's deceit of the Indians and their revenge upon him; and the story of the Pennacook Indian princess Wenunchus, who drowned in the Merrimack as a result of a squabble between her father Passaconnaway and her husband Winnepurkett of Saugus. Back in Whittier's day, poems were sometimes epics, running thousands of lines. People would read them outloud to each other in the evening by lamplight or by the fire. I recorded myself reading The Bridal of Pennacook (in part), to get a feel for the language. That poem also provided a good geography lesson about upper reaches of the Merrimack River, which was the heartland of the Pennacook indians. The poem mentions Turee's brook, Contocook, "the Crystal Hills to the far southeast", Sunapee, Snooganock, Coos, Umbagog Lake, Ammonoosuc, Chepewass, "the Keenomps of the hills which throw/Their shade on the Smile of Manito"; Kearsarge, Babboosuck brook, Otternic, Sondagardee, Squamscot, Piscataquog...does anyone know these places?? St. Anne's Church, the Society of Mary (Marists) and the French Canadians of Greater Lawrence3/7/2018 Above: St. Anne's Church, Lawrence. Completed 1883, closed 1991 The French Canadians in Lawrence "Although less numerous in Lawrence than in Lowell, the French Canadians still contribute an important element to the Catholic population of this city." (from Byrne's History of the Catholic Church in New England, 1899) As described in another blog post, French Canadians began emigrating to manufacturing centers in New England after the Civil War. They brought with them a concept of La Survivance, an insistence on maintaining their French language and their culture, expressed to a large degree through their own Catholic institutions: French churches and French schools. The French-speaking Canadian immigrants were comprised of Québécois from the province of Quebec; and Acadians, the descendants of French-speaking settlers of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia (many of whom were forcibly moved to Louisiana after defeat by the British in 1755, where they became known as Cajuns). A French Parish One of the first things the French-speakers did in Lawrence was to create their own parish. This was no easy task. The Augustinian order was firmly in charge of the churches on the north side of the Merrimack River. So-called national parishes (foreign-language churches that catered to specific ethnic groups) in Lawrence were usually organized as mission churches of St. Mary's parish. St. Mary's was the main "cathedral", run by the Augustinian Fathers. Thus, the German-speaking Church of the Assumption, the Polish-speaking Holy Trinity Church, the Lithuanian-speaking St. Francis and the Portuguese-speaking Sts. Peter and Paul were all mission churches of St. Mary's, and were overseen by the (Irish-dominated) Augustinians. In contrast, through the importation of recognized French-speaking religious orders, the French were allowed to have their own independent parish in the Lawrence area. Eventually, St. Anne's parish grew to encompass four churches: St. Anne's, Sacred Heart in South Lawrence, Our Lady of Mount Carmel (Methuen) and St. Theresa (Methuen). All were essentially founded by the Marist Fathers, and in most cases were run by the Marists for decades, along with St. Joseph's in Haverhill, as further described below. The Marists come to New England The order was formally recognized by the Church in 1822. It was formed after a group of soon-to-be priests led by Jean-Claude Courveille and Jean-Claude Colin made a pilgrimage to the shrine of the Black Virgin at the cathedral of LePuy in France. There, they experienced healing while praying before the statue of the Virgin. They came to believe the Blessed Mother wanted to help the Church through a society consecrated to Mary and bearing her name. The Marists' first missionary work was in the remote areas of the Diocese of Belley in southeast France. The Marist order (not to be confused with the Marianist order), first focused their American mission in Louisiana, a bastion of French Catholicism, taking charge of St. Michael's in Convent, Louisiana in 1863 and overseeing two parishes and a high school. The fact that they arrived during the Civil War did not seem to dissuade them. Until 1880, the Marists were content mainly to operate in France; however, in that year, citing the principles of the French Revolution, the government of France ordered the closure of all Catholic religious orders in France. "With the expulsion of religious orders from France in 1880, the Marist General Administration sought new opportunities for their members in the United States. There were more opportunities than they could handle, but no more than in the New England states, where French-Canadians were pouring in to find employment in the mills that had sprouted up all over the area." (From the 150th Anniversary pamphlet of the Marist Order, www.societyofmaryusa.org/pdfs/Marist150YearsofGrace.pdf) The leadership of Rev. Elphage Godin, S.M. Like Rev. James O'Donnell, O.S.A. who brought the Augustinians to Lawrence, and Rev. Andre-Marie Garin, O.M.I., who led the expansion of the Oblates in Greater Lowell, Rev. Elphege Godin, S.M., was a larger-than-life figure. Above: Father Elphege Godin, S.M. (from the Society of Mary website) Born in 1847 at Trois-Rivieres, P.O., Canada, Father Godin was ordained in 1871 for the diocese of Trois-Rivieres (Quebec), where he served for several years. He joined the Society of Mary in France in 1878. (Source: Marist 150th anniversary pamphlet.) His first assignment as a Marist was to teach at Jefferson College in Convent, Louisiana, and to preach parish missions. Able to speak English as well as French, his services as a preacher were much in demand. In the early part of 1881, he was invited to preach in Old Town, Maine, and spent some time as a missionary in Waterville, Augusta, Biddeford and Brunswick, Maine, and also in Manchester and Lebanon, N.H. In May of that year, Father Olivier Boucher, the pastor of St. Anne’s in Lawrence, MA asked his assistance. (ibid.) Completion of St. Anne's Church "In 1869 there were only four hundred French Canadians in Lawrence. They were given religious instruction in their own language in the basement of the Immaculate Conception church. [Note: the so-called "basement church" for ethnic immigrants is still a practice today in the Catholic Church.] Knowledge of the success achieved by the French Oblates in Lowell reached them, and a movement was begun which resulted in a visit from [the Lowell-based Oblate] Father Garin, and the holding of regular services in Essex Hall." "In 1882...Rev. Elphage Godin, the well-known Marist...entered upon his duties in this important centre of French Canadian colonization. Under his management the church was speedily finished and dedicated, the ceremony being performed by Archbishop Williams on Low Sunday, 1883." (from Byrne's history of the Catholic Church in New England, 1899) "It is generally agreed that St. Anne’s Parish in Lawrence was the ‘Mother Parish’ of all Marist-operated parishes in New England." (www.societyofmaryusa.org/about/history-northeast.html) St. Anne's was followed by the establishment of Marist-run missions that became four French-speaking parishes in the Greater Lawrence area: Sacred Heart (Marist-operated for 101 years), St. Joseph (85 years); and in Methuen, Our Lady of Mount Carmel (78 years) and St. Theresa (61 years).(Ibid) Below: A 2015 picture of Sacred Heart Church, South Lawrence. Source: Wikipedia The Marist Fathers provide additional French-focused churches in the area Sacred Heart An 1899 history of the Catholic Church in New England noted that St. Anne's church was bursting to the gills with worshipers. This problem was remedied with the construction of Sacred Heart in South Lawrence, which eventually became a grand complex. The first church on the site was built in 1905, apparently being replaced by the current church starting in 1916. "The oldest building on the site is the 1899 school, a three-story, highly ornamental brick structure designed in the Romanesque Revival style. The convent, rectory, and second school were built in 1920, 1924, and 1925, respectively. The ground level of the church was constructed in 1916 as a one-story brick structure, but between 1934 and 1936, the original church was incorporated into a Gothic Revival-style building constructed of polychromatic ashlar." (Source: Sacred Heart Complex Approved for Nomination to the National Register of HistoricPlaces, https://www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcpdf/pressreleases/91911_Sacred_Heart_Complex_Lawrence.pdf) Sacred Heart was closed in 2005 and has since been taken over by a Catholic-inspired group not affiliated with the Catholic church, who hold Latin masses in the facility. St. Joseph's, Haverhill St. Joseph Church was founded in 1871. It was Marist-run from 1893 for eighty five years, when Father Godin became the superior, until 1978. "In the year 1870 the French Canadians of Haverhill were numerous enough to found a St. Jean Baptiste Society, whose president was soon deputed to visit Bishop Williams [in Boston] and request the services of a Canadian pastor. Through the efforts of Father Garin, of Lowell, an Oblate priest, Rev. Father Baudin, was sent to the town on Christmas Day, 1871. A hall on Water street had been fitted up as a chapel, and in that humble edifice Father Baudin held services and baptized two children. This was the foundation of the present flourishing parish of St. Joseph." (Source: Byrne's history of the Catholic Church in New England, 1899) A more imposing edifice was constructed in 1876. "The growth of the congregation, both by new arrivals from Canada and by local increase, compelled the erection of a church and at the same time made it financially possible. December 17, 1876, Archbishop Williams blessed the edifice which stands on the comer of Grand and Locust streets, and administered confirmation to nearly a hundred persons." (Ibid.) At some later date, the church on Bellevue Avenue was constructed, which stands to this day. Father Godin served for ten years at St. Joseph, firmly establishing the Marist presence, which continued under the tutelage of that Order until 1978. The French parish was closed in 1998, when St. Joseph merged with three other formerly ethnic parishes of the Mount Washington neighborhood: St. Michael (Polish), St. George (Lithuanian) and St. Rita (Italian). The combined new parish, All Saints, is housed in the former St. Joseph's building on Bellevue Avenue. The elementary school at St. Joseph's was the subject of a legal dispute when an anti-immigrant, pro-American Haverhill School Board ordered all schools to teach only in English in 1888. At the time, instruction was being given in French by Les Soeurs de la Charité d'Ottawa (Soeurs Grises de la Croix), the so-called Grey Nuns of the Cross from Ottawa. This incident will be covered in a separate blog entry, as will be the Grey Nuns, who had a prominent role in the Merrimack Valley including running the main hospital in Lowell for a century. St. Theresa’s (St-Thérèse) and Our Lady of Mt. Carmel (Notre-Dame du Mont Carmel), Methuen Above: St. Theresa, Methuen. From Our Lady of Good Counsel website Our Lady of Mt. Carmel was built in 1922 as the first French-Canadian church in Methuen, as a "mission church" of St. Anne's In the mid-1930s, the Marist Fathers established a second mission church, St. Theresa, to serve the growing French Canadian population there. Our Lady of Mt. Carmel closed in 2000. The ministry of St. Theresa's was eventually taken over by the Augustinians, and the church was merged with St. Augustine's in Lawrence (my church growing up) to form Our Lady of Good Counsel parish. They are apparently now under diocesan tutelage. The Novitiate in Tyngsboro, Mass. In 1922, the Marists purchased a portion of Wonalancet Farm in Tyngsboro, a suburb of Lowell. You may remember from other blog posts that this is where the hapless Wonalancet, sachem of the Pennacook Indians, lived out his days under the watchful eye of Captain Tyng following King's Philips War of the mid 1670s. They initially used the historic Tyng house, pictured below (which burned down in 1981) before building a more modern set of structures. Below: The historic Jonathan Tyng house, built circa 1675, burned down 1981 Above: The Marist novitiate (for training new members of the Order), late 1960s (source http://academic2.marist.edu/foy/maristsall/essays/innovation_academy.html) After World War 2, the Marist Order decided to establish a college in the United States, and the location was either going to be in Poughkeepsie, New York, where they had a large Novitiate, or in Tyngsboro at this site. Marist College was ultimately established in Poughkeepsie. If it had been established in Tyngsboro it no doubt would have been a rival of Merrimack College, the Augustinian college in North Andover. In 1979, following a significant decline in new members to the order, the Marists sold the Tyngsboro property to Wang Laboratories, who used it for their Wang Institute until 1988, when it was sold to Boston University as a corporate campus. In 1996, a charter school, Innovation Academy, began operating on the property and they apparently bought the land outright in 2008. Legacy of Father Godin "Father Godin was a Marist pioneer who planted the seed, nurtured and cared for it while it grew and, by the time he took leave of this earth, saw it firmly established. When he began at St. Anne’s in Lawrence, MA, in 1882, this was the only house the Marists had in the whole northeastern section of the country. When he died, 51 years later, in 1931, besides St. Anne’s the province included Our Lady of Victories, Boston, MA; St. Bruno’s, Van Buren, ME, St. Mary’s High School, Van Buren, ME, St. Mary’s College, Van Buren, ME (1887 to 1926), St. Joseph’s, Haverhill, MA, Our Lady of Pity, Cambridge, MA, Sacred Heart, Lawrence, MA; Immaculate Conception, Westerly, RI, St. John the Baptist in Brunswick, ME, St. Charles Borromeo in Providence, RI, St. Remi’s, Keegan, ME, a novitiate on Staten Island, NY, and two minor seminaries: one in Bedford, MA and one in Sillery, P.Q. Canada." Sadly, the time of his death marked the beginning of a long decline of the French-speaking churches of the Marists, most of which have since closed as a result of significant postwar demographic changes. A remaining institution of prominence is the Lourdes Center in Boston. "In Kenmore Square, the Marist-run National Lourdes Bureau of America, founded in 1950 by the Marists at the request of Archbishop Richard Cardinal Cushing, and through arrangement with the Bishop of Lourdes, France, mails out an average of 22,000 small bottles of Lourdes water every month. The ministry also publishes a bi-monthly newsletter to 47,000 readers, sponsors annual pilgrimages to Lourdes, and conducts daily Mass and confessions for students, residents, hotel workers and guests, as well as shoppers and visitors to the Kenmore Square area." (Source: Boston Pilot article, February 20, 2015) Below: 1950 Banquet to celebrate the cherished Marist Fathers of St. Anne's School, held in the gym at Central Catholic High School. Source: Lawrence History Center The Marist Brothers and Education The educational legacy of the Marists in Greater Lawrence is as important as their ecclesiastical legacy. Unlike some of the other religious orders, the Marists were strongly represented by brothers, who had taken vows but were not ordained priests. The Marist brothers were typically educators at the primary and secondary level. The educational attainments in the Merrimack Valley of the Marist Brothers will be covered in a separate blog entry. Their crowning legacy was probably Central Catholic High School, which was essentially spun off of the St. Anne's School of Lawrence by Brother Mary Florentius in 1935. Below: Central Catholic High School, Lawrence. It is still a Marist institution.  Other French-Canadian Institutions in Lawrence The Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste was once to the Franco-American community what the Knights of Columbus was to the Italians or the Hibernians was to the Irish. The Social Naturalization Club was founded in 1915. Located on Lowell Street in Lawrence, it hosted prominent political leaders, like Rose Kennedy in 1962 and Mrs. Joseph P. Kennedy in 1985. Later it was located at 120 Broadway. The LaSalle Social Club on Andover Street in Lawrence was another prominent Franco-American social institution. The community also had a French paper of their own, Le Progres. [Please help me add to this list.] Above: the interior of St. Anne's church, Lawrence, 2016. It has basically been abandoned and neglected since it closed in 1991. Source photo: Eagle-Tribune

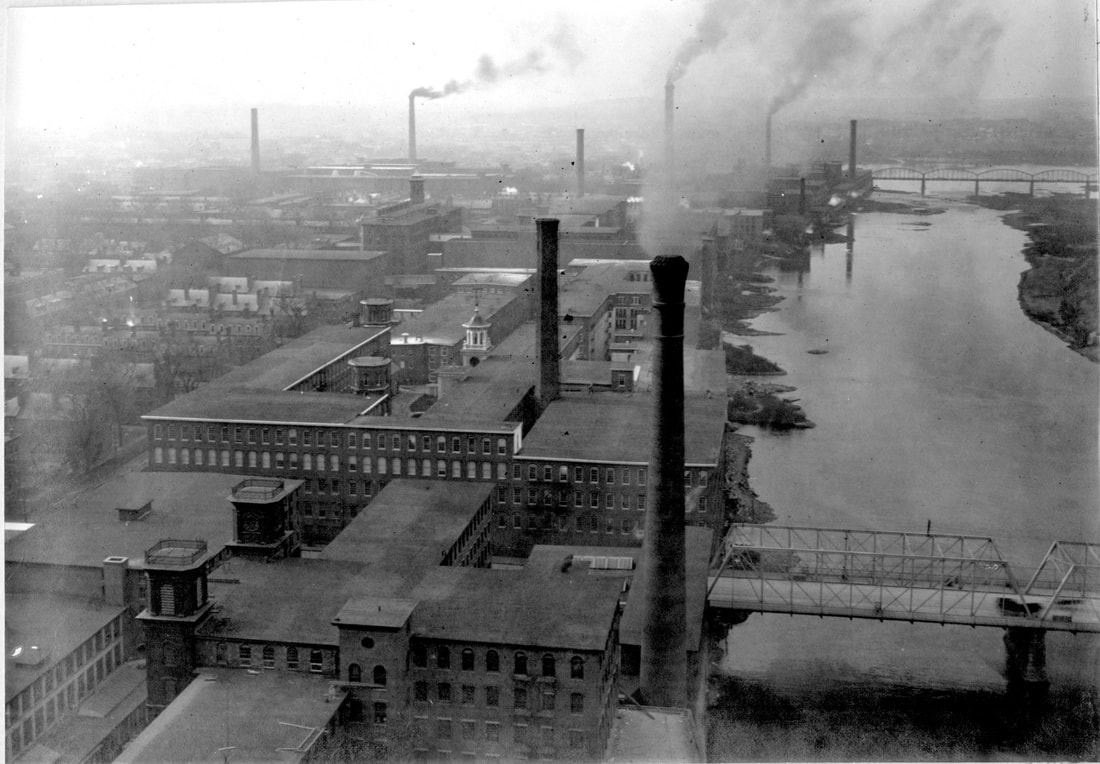

Above: Lowell in its manufacturing heyday. Source: UMass Lowell Introduction: Lowell before the French Everyone knows the story of Lowell's original workers, Yankee-farm girls who worked in the textile mills to earn a little money before returning to rural farms to get married. Introduced in 1826 upon the founding of Lowell, this system of labor collapsed when destitute Irish immigrants poured into the area following the Potato Famine. These poor Irish provided cheaper labor under worse conditions than the mill girls could ever tolerate. A few decades after their arrival in Lowell and other cities, the Irish had established a foothold, basically creating the Catholic Church in New England along the way. They also began to participate successfully in local politics. By 1882, Lowell had an Irish-American mayor. In the Merrimack Valley and elsewhere, later generations of immigrants, usually Roman Catholic, had to contend with Irish dominance of key institutions in the Church and the local government. This will be covered in other blog posts. The first immigrant group after the Irish in the Merrimack Valley were the French-Canadians. They are also the only immigrant group to arrive by train. French-Canadian Immigration French Canadian immigrants had been crossing the border into the United States since the 1840s, searching for better farming conditions and settling along the northern reaches of New York State, Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine, where in some towns they comprised the majority of the population by the time of the Civil War. However, after the Civil War, migration patterns focused on New England's growing manufacturing centers. French-Canadians ultimately were concentrated in Fall River, Lowell, Manchester (N.H.), Woonsocket (R.I.), New Bedford, Holyoke, Worcester, Lewiston (Me.), Biddeford (Me.) and a few lesser manufacturing towns. (Source: The French Canadians in New England, by William MacDonald, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 12, No. 3 (Apr., 1898), pp. 245-279, Oxford University Press.) Lowell had a total population of approximately 41,000 in 1870, of which 3,000 were French-Canadian, compared to around 20,000 Irish. By 1881, there were approximately 10,000 French Canadians, showing the tremendous rate of immigration. By 1909, the number of French Canadians had nearly caught up to the number of Irish (including in both cases children of immigrants): 20,000 versus 22,300. (Source: The Record of a City: A Social Survey of Lowell, Massachusetts, George Frederick Kenngott, Macmillan Company, 1912) In Lowell, like elsewhere, French Canadian immigrants adhered to the ethos of la survivance:

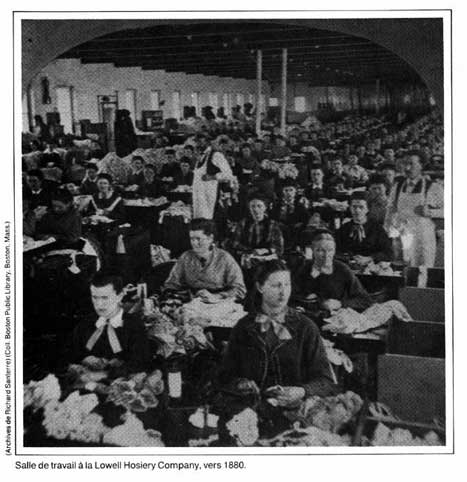

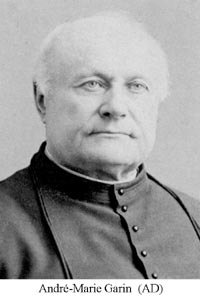

(From French Canadians in Massachusetts Politics, 1885-1915: Ethnicity and Political Pragmatism by Ronald Arthur Petrin, Balch Institute Press, 1990) La Surivance led the French-Canadians to insist upon their own institutions, and it ended up being the Oblates (and a number of other French-speaking religious orders such as the Grey Sisters of Ottawa) who provided them. Below: French-Canadian women at work in a Lowell hosiery factory, 1880.  Left : The heart of Little Canada, Hall & Aiken Streets, Lowell, 1923. Source: Lowell Sun The "Little Canada" of Lowell was pretty much one of these "dismal proletarian districts". It was situated along the Merrimack River in central Lowell, behind the textile mills around Aiken, Austin, Cheever, Hall, Tucker, Ward, Ford, Decatur, Race, Merrimack and Moody Streets. Below: The memorial plaque for Little Canada (Le Petit Canada), the core French-Canadian neighborhood of Lowell, Aiken Street. The neighborhood was demolished for urban renewal in 1964. It was into this area (and nearby French-Canadian neighborhoods) that the Oblates came in 1868, to serve the religious and cultural needs of the burgeoning French-Canadian population of Lowell. The Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate The Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate (OMI) was founded in 1816 by Saint Eugene de Mazenod, a French priest born in Aix-en-Provence in the south of France. In 1841, Canada became their first foreign mission. With steady reinforcement from France and Canadian recruits, they moved up the Ottawa Valley, and in 1845 into the North-West, where the establishment of the Catholic Church in western Canada was largely Oblate work. Coming to the United States and Lowell By 1853, the Oblates were following the French speaking population into the United States, setting up a mission in Plattsburg, New York, followed by one in Buffalo, New York. By 1857, they oversaw St. Joseph's in Burlington, Vermont. In December 1867, Father Florent Vandenberghe, provincial superior of the Oblates, based in Montreal, met Archbishop John J. Williams of the Archdiocese of Boston while attending the dedication of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Burlington, Vermont. Arrangements were made for two Oblate priests to be sent to Lowell at the invitation of the Archdiocese, to minister to the growing French Canadian population. Below: Father Florent Vandenberghe of Montreal, Provincial Superior of The Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, who directed two Oblate priests to Lowell in 1868 Founding of St. Joseph's and Immaculate Conception churches (both still active today) Following their conversation in Burlington, Archbishop Williams had been active, and found a former Unitarian Church on Lee Street, Lowell, for which he entered negotiations, hoping it would be the future site of the Oblates' parish. In March, when weather conditions improved, Father Vandenberghe traveled with Bishop Williams to view the site, but expressed some concern about the ability of the small French Canadian population there to sustain a parish of its own. This prompted Bishop Williams to propose that the Oblates establish two parishes, the second an English-speaking parish, to which Father Vandenberghe agreed. Father Vandenberghe sent two priests, Fathers Andre Garin and Father Lucien Lagier, who arrived in Lowell on April 18, 1868. Within a few short weeks, the Canadian Catholics contributed enough money for a down payment on the Lee Street Church, and dedicated it to St. Joseph on May 3, 1868, the city's first French-speaking parish. The second parish agreed to was temporarily located at St. John Chapel, initially part of St. John Hospital (then at the corner of Fayette and Stackpole Streets and now part of "the Saints" campus of Lowell General Hospital), and dedicated to the Immaculate Conception. (Source: Oblates Come to Lowell to Serve French Canadian Catholics, by Thomas Lester, Friday, January 19, 2018 https://www.thebostonpilot.com/opinion/article.asp?ID=181298) Below: Immaculate Conception, East Merrimack Street, Lowell (rebuilt after fire 1912-1916). Source: Wikipedia Despite the successful foundation of two churches, it was soon determined that the heart of the neighborhood lacked a church. The aforementioned Father Garin made it his life's work to establish a church there, dedicated to St. Jean Baptiste. Below: Fr. Andre-Marie Garin, OMI, "L'inoubliable Fondateur" "Father Garin was a native of France, and a missionary worthy of comparison with Marquette, Breboeuf, and others whom that ever-vital nation has sent to our shores. He had traveled by canoe and snow-shoe through Labrador, and on the coast of Hudson's Bay; had lived without food for forty-eight hours on an ice-floe; and had translated books into rare Indian tongues. His vigorous presence aroused the Canadians of Lowell." (from The History of the Catholic Church in the New England States, Volume I, by Rev William Byrne et al, 1899) Like Father O'Donnell who basically founded the Augustinian presence in nearby Lawrence, Father Garin was a larger-than-life figure so needed by recent poor immigrant communities. In 1869, Father Garin performed the first French language Mass in Lawrence, where the French speaking population still only numbered in the hundreds. In due course, another French-speaking religious order, the Marists, would take over the French parishes of Lawrence. That is the subject of another blog post. In 1893, he was chosen as the delegate to the meeting of the General Chapter of the Oblates in France. Then he turned his attention to completing St. Jean Baptiste. Establishment of St. Jean Baptiste The new church was part of St. Joseph parish. "St. Joseph would be expanded several times in the following years, but never proved adequate for the burgeoning French-speaking population in the Lowell area. To solve this problem Father Garin hoped to build a new church, and in 1887 purchased land on Merrimack Street on which to do so, the eventual site of St. John the Baptist, dedicated on Dec. 13, 1896." "Sadly, Father Garin would not live to see its completion, having died the year before on Feb. 16, 1895. At the time of his arrival in 1868, there were 1,200 French-speaking Catholics in Lowell, and by the time his new church was completed, it was responsible for serving close to 20,000." (Source: Byrne history, 1899) The church was located in the heart of Little Canada and served as the focal point of the community for decades. "St. John the Baptist's church, which is now the principal French church of Lowell, being fully as large as St. Joseph's, and much more imposing, fronts on Merrimack street, somewhat west of St. Joseph's. It is a bold Romanesque structure, built of granite, the prevalent material in Lowell public buildings. A bronze statue in front immortalizes the resolute features of its founder, Father Garin." (Ibid.) As noted by Byrne in his history of the Catholic Church in New England, "The French church is popular even among the Irish-Americans of Lowell, numbers of whom attend its services. Attendance of Canadians, however, at the services in churches other than their own is rare." With the destruction of the Little Canada neighborhood in 1964, following years of population decline as post-war populations moved to the suburbs, in 1993 St. Jean Baptiste was closed by the Archdiocese. It was then resurrected as the sole Spanish-language "national parish" church in New England (see below), which was closed in 2004. The structure still stands and is being converted to an event space. Below: Recent Photo of St. Jean Baptiste, now an event space. Source: https://www.lowellshistoriccathedral.com/ Creation of a separate OMI Province in 1883 "This high esteem which the Oblates enjoyed here, and the success of their missionary tours, addressed to the needs of French and English congregations elsewhere, led to the creation, in 1883, of a separate province of the Order for the United States, with its headquarters at Lowell. In the same year a novitiate was founded in the suburb of Tewksbury." (covered below)(source: Byrne 1899 history) Establishment of Notre Dame de Lourdes in 1908 "At the dawn of the [twentieth] century, the need for a church in another section of the city became acute. Many of the Franco-Americans who lived some distance from St. Joseph’s Church were abandoning their religious practices. Despite their relative poverty, the people organized and founded Notre Dame de Lourdes parish in 1908 after restoring an abandoned Baptist temple. A new and modern church complex was constructed in 1962. For many years, while serving the community, the parish was greatly involved with ministry to the many immigrant minorities in the area. A special center reached out to the needs of the many Southeast Asians who have been migrating to Lowell since the war in Vietnam. The church was an active member of many interfaith social programs that reached out to the needy of that part of the city. (Editor’s Note: Following the reconfiguration of the Archdiocese of Boston, Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes was suppressed in 2004.)" (Source: https://francolowellma.wordpress.com/religious-orders/oblates-of-mary-immaculate/) Establishment of Ste Jeanne d’Arc Parish in 1922 "St. Jeanne d’Arc Parish was established on December 30,1922, by William Cardinal O’Connell. The Oblates of St. Joseph Parish had been ministering to the Franco-Americans on the Pawtucketville side of the Merrimack River area since 1920. A small school, built in 1910 by Father Campeau to accommodate younger children, was expanded and transformed into a school and chapel. The first Mass was celebrated there on the third Sunday of April 1921. By a decree of the General House, dated January 30, 1923, Father Léon Lamothe was appointed first Superior and the new residence was officially established. A new stone church was completed in 1929. Later, a new slanted roof was added to improve the outside lines of the structure, and the interior of the church has been completely renovated in conformity with the latest liturgical requirements. (Editor’s Note: As a result of the reconfiguration process, the Archdiocese of Boston ordered the suppression of Ste-Jean d’Arc parish in 2004. Ste-Jeanne d’Arc grammar school, administered by the sisters of Charity of Ottawa is still active and currently operates under the auspices of St. Rita’s Parish.)" (Source: https://francolowellma.wordpress.com/religious-orders/oblates-of-mary-immaculate/) The Oblates in Billerica - St. Andrews "Before Saint Andrew’s Parish was established [in North Billerica], thousands of Irish people, due to political oppression along with the great potato crop failure of the 1840’s and 1850’s, [had] made the trek to New England in order to seek jobs in the nearby Talbot and Faulkner mill complexes. They brought with them few material possessions, but they did bring with them a sound and living faith. These Billerica Catholics had to walk about five miles to the nearest Catholic church in Lowell to worship. In 1868, the remarkable Father Andre Garin of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate established a mission parish for the town of Billerica. He helped the small congregation arrange to buy the now-abandoned Universalist church. After the purchase, they moved it to Mill Street, now known as Rogers Street, and placed it under the patronage of the Apostle Saint Andrew. In the end, $4000.00 had been spent; but the people finally had their own church. For forty years, Saint Andrew’s Parish was in the care of the Oblate Fathers. They would come in from Lowell, at least once a month, to celebrate Mass and handle all pastoral matters. Some of these priests served for but a few months, while others remained for several years. In 1890, Father James Maloney, O.M.I. realized the need for enlarged facilities to accommodate the increased number of parishioners. His program of renovation and expansion was carried out with the physical as well as the financial help of the people. Through their generosity and selflessness, the dedicated people managed to complete a $6,910.44 renovation that increased the size of the church by one third. Imagine the sacrifices that were made considering that the average daily wage was about 85 cents!" From http://billericacatholic.org/?page_id=49 The Oblates in Tewksbury Above: The Former Oblate Fathers Novitiate

In 1883, the Oblates in Lowell founded a Novitiate, an institution typical of any Catholic religious order, in which Novices are trained and decide whether they are called to the order, either as priests or as lay members (monks and nuns). These days, it is a retirement home for Oblate priests from around North America. The Oblates and Spanish-speaking Catholics of Lowell, 1970-2004 When the first wave of non-English speaking Catholics arrived with the French-Canadians, these French-language Catholics were able to bring religious orders from Canada such as the Oblates and the Marists, to provide French language instruction. Subsequently, in the 1890s through the 1920s, the archdiocese allowed the formation of "national parishes" dedicated to the needs of a particular ethnic group, Italian, Polish, Portuguese and what have you, although they were typically run by diocesan priests of Irish background. After World War II, the "national parish" practice largely ended as these immigrant groups all became assimilated and many moved to suburbs, leading to the closure of ethnic parishes in inner cities. When Puerto Rican and other hispanic immigrants began arriving in the Merrimack Valley in the early 1970s, it triggered a debate within the Archdiocese: do we establish a separate Spanish-language national parish? Eventually the answer was: no. Integration was seen as more favorable --although (begrudging?) accommodations were made in allowing "basement chapels" to be formed where worship was conducted in Spanish. The sole exception to this rule was a Spanish-language parish in Lowell, Nuestra Seniora del Carmen, in the former St. Jean Baptiste church.

|

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed