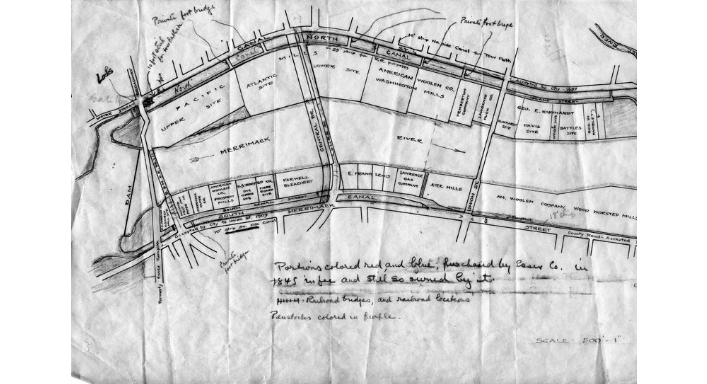

Above: Katherine O'Keefe O’Mahoney, born Ireland 1855, died Lawrence, Mass. 1918 (Source: Lawrence, Massachusetts by Ken Skulski, 1995) The Backstory Before there was Lawrence, there was ye olde New England: clapboard farmhouses, village greens, slow-moving farmers who mended their stone walls and carted their produce to market. This is how things were in 1845, the year Lawrence was founded as a town. Things in 1845 really weren’t all that different from 1645, two hundred years earlier, when the area was first settled by English Puritans in the towns of Andover and Haverhill. The ancient towns were later carved into the towns that we know today – Methuen, Salem N.H. (both formerly part of Haverhill), North Andover (the original part of Andover)…and Lawrence. Sure, the railroad had been introduced a decade earlier, and the Puritans had mellowed somewhat. People were no longer executed for witchcraft or whipped for heresy. But the culture was basically the same as it had been for generations. The original Puritan settlers had come forth and multiplied, cleared the land, built meetinghouses. Some of them went off to sea, chasing whale oil or Far-East silks and spices; or enterprisingly built waterwheels to grind their neighbors’ grain. Some of the local militia boys had gone off to the Battle of Bunker Hill and other early encounters of the Revolution. Basically, however, people farmed, traded, read their King James Bibles, attended meetinghouse, lived and died. Things were homogeneous and consistent, generation after generation. Below: Typical New England farm of the early 19th Century, similar to Bodwell's Farm in what became Lawrence (Source: New England Historical Society) Then, in the second half of the 1840s, two things happened: (1) industrialization and (2) a refugee crisis. Here Come the Factories The fast-moving tributaries of the Merrimack River had always powered waterwheels – little mills that were used to grind grain, saw logs into boards, or run a few looms to supplement the homespun cloth. However, in the 1840s, the mills being planned were different: they would now be on a grand scale. The immense new wealth of the spice trade and whaling was chasing new investments, and could finance endeavors on a previously unimaginable scale. The industrial revolution was underway in Britain and provided the technology. The planned textile city of Lowell was the first example, as we all know, but bigger and bigger factories could be planned. So a group of rich Boston merchant pooled their capital to form the Essex Company. In 1845 this company started to build Lawrence in a backcountry corner of Essex County, smack in the middle of farmers’ fields that had been cleared two centuries earlier. Their project – to build the largest dam in the world across the Merrimack and force its waters down two long canals to power dozens of enormous mills – required a lot of labor, the cheaper the better. Below: Plan for Lawrence showing new dam, canals and plots for water-powered textile mills, 1845 (Source Digital Public Library of America) Here Come the Irish Refugees And who should conveniently show up but a bunch of Irish refugees who could be put to work for pennies a day? These rag-clothed, impoverished, filthy bands of people were escaping the biggest humanitarian crisis of their time. The Irish Potato famine was so severe it killed one third of the people and forced another third to flee. The Famine Irish had arrived on dangerous, unseaworthy “coffin ships” operated by unscrupulous people-runners looking to exploit the desperation of the refugees. A risky voyage across the water was nevertheless preferable to staying in Ireland. Below: A So-Called Coffin Ship Leaving Queenstown (Now Cobh) Ireland, 1848 The Irish migrants crowded the port of Boston, then made their way inland, likely on foot, looking for work. The stream of refugees began in 1847 and did not abate until the mid-1850s. At Lawrence, they formed their refugee camp – the shantytown on the southern bank of the Merrimack – and the men started working on the dam. One of these laborers was my great great grandfather, Jeremiah Driscoll, arrived from Ireland in 1851 at age 29. He worked as a laborer for the Essex Company. His home address in the Lawrence town directory, once the town was big enough to have a directory, was “Shantytown, South Side.” Other Irish built a shantytown/refugee camp on the plains above Haverhill Street, near the Spicket River. A report from 1870 stated that some shanties had to be cleared for construction of the Lawrence reservoir. One of them was 120 feet long, and made of rough boards. It housed 80 people, mostly single men but also a family who built the place and charged the boarders a half penny a day to shelter there. Below: Derogatory Cartoon Depicting Shanty Irish Irish Pride in Early Lawrence Fast forward thirty-five years or so to 1882. Lawrence has grown from a couple hundred residents to 38,000…and around half of them are Irish. Although the town is seven square miles, most folks are concentrated in walking distance of the mills lining the river, spanned now by three bridges. There are by this time over a dozen large textile mills with more being built. The Irish, though largely still poor, have survived massive prejudice and exploitation within a largely hostile Yankee society. What do they do to show their pride? Do they march in a St. Patrick’s Day parade? Hardly – the first proper St. Patrick’s Day parade in Lawrence wasn’t until the 1900s. Go to a Riverdance concert? Listen to the Dropkick Murphy’s? No: they celebrated their Catholic faith by building magnificent churches and then organizing their lives around them. Below: Interior, St. Mary's Church, erected Lawrence, Mass. 1871

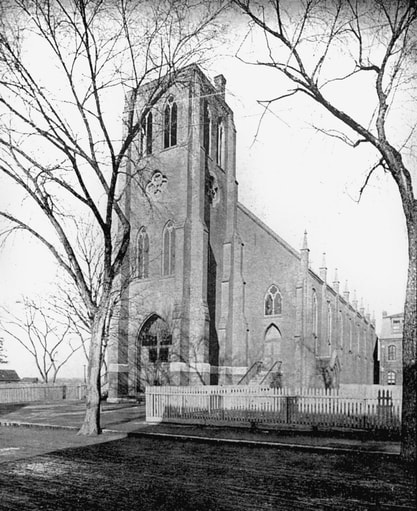

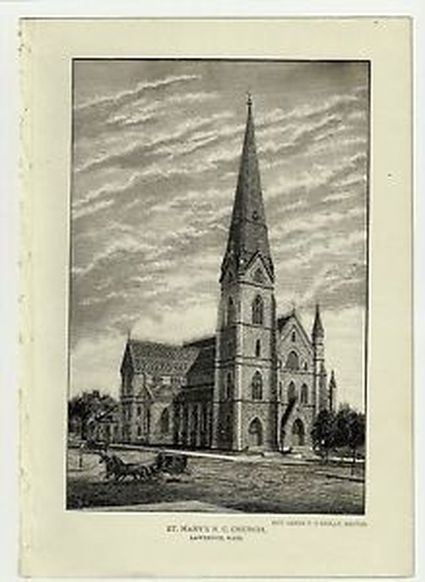

As one observer wrote, the Irish were known to spend their money on beautifying their houses of God before they beautified their own homes. Indeed, in 1882, three grand churches had been constructed of granite and brick in Lawrence – Immaculate Conception on Chestnut Street, St. Mary’s on Haverhill Street, and St. Lawrence O’Toole at the corner of Essex and Union Streets (it was renamed Holy Rosary in 1904 when the new St. Laurence O'Toole was built on East Haverhill Street). Yet at the same time, many Irish in Lawrence still lived in shanties. The last shanty was not torn down until 1894. Above: Immaculate Conception Church, Chestnut Street, Lawrence (Source: Queen City Blog). Lawrence's first permanent Catholic church, torn down 1991.The sense of Irish pride in their Church and its institutions – its grand churches, its rigorous schools, its charities like orphanages and hospitals – is captured in an 1882 book, “Catholicity in Lawrence” by Katherine O’Keefe O’Mahoney. According to Ken Skulski’s history of Lawrence, O'Keefe was “an author, lecturer and educator”. Irish-born, she graduated from Lawrence High School in 1873 (a rarity for girls, especially an immigrant girl), and then she started working there as a teacher. “Robert Frost considered her one of his favorite teachers. She was also among the first Irish-American women to lecture in New England. Her books include A Sketch of Catholicity in Lawrence and Vicinity (1882) and Famous Irishwomen (1907).” She also published a newspaper for Irish-American Catholics in Lawrence and conducted Irish classes there. She died at her Tower Hill home in 1918 at age sixty three. (Source: Ken Skulski’s Lawrence, Massachusetts.) For the about the first thirty year's of Lawrence's existence (until French Canadians started to arrive), pretty much the only Catholics in Lawrence were Irish. Reading O'Keefe's proud descriptions of St. Mary’s Church, you can get a sense of the importance of a magnificent church like this to the community:

Below: St. Mary's Church, Lawrence, Mass. erected 1871 For her, the priests are towering figures, and funerals of priests are the equivalent of a funeral for a head of state. The following is from her description of the 1875 funeral of Father Louis Edge, O.S.A., who built St. Mary’s along with the Augustinian Order. She claims that 10,000 people viewed his body lying in state in his coffin in front of the altar. Note the participation of the numerous Irish social and religious organizations: “Early on Monday morning, crowds began to assemble in the vicinity of the church, awaiting the opening of the doors. The Ancient Order of Hibernians, numbering nearly 150 men, were the first to enter, and to them was assigned the East wing; after them came the Ladies’ Sodality of St. Mary’s Church, with medals and white veils. They numbered over seven hundred, and presented a beautiful appearance. The Irish Benevolent Society, headed by the Lawrence Brass Band, were the next to enter the church. They numbered nearly two hundred, and bore a silken mourning banner; they were seated in the Gospel aisle. Next came the Ladies’ Sodality of the Church of the Immaculate Conception, in white veils, similar to St. Mary’s Sodality; they had been assigned to them the West wing. After them came the Men’s Sodality of St. Mary’s Church, wearing white sashes and white crosses; they were placed in the Epistle aisle. And then came the Catholic Friends’ Society, and the Conference of St. Vincent de Paul. The church was tastefully draped in mourning, the black festoons in the galleries were relieved with white rosettes, and the mourning on the altar with small white crosses. Over the altar was a large cross, formed of blazing gas-jets; and there was a star of gas-jets [!] in front of the organ. When the clergy, forty-six in number, entered the sanctuary to chant the Solemn Office, the scene was truly grand and impressive.” She then goes to name each of the forty six priests in attendance, treating each one as a celebrity. “The architect of this magnificent structure was [Irish-born] P. C. Keely of Brooklyn, N. Y.,” she continues. He was in fact one of the preeminent architects of Catholic churches in the Northeast in the latter half of the nineteenth century. “The stone work was under the supervision of James Trainor of Boston; the wood work was superintended by James Bulger of Burlington, Vt; and the painting, as we have recently stated, was by Schumacher of Portland, Me. Its cost was over $200,000.” Given that this amount was largely raised by small donations from the commuity, it is quite an amazing sum considering that a laborer made a couple dollars a week. Later, she describes the fundraising campaign to pay for the bells of the church (weighing a total of over 10,000 lbs). The list of donors reads like a directory of Irish residents of Lawrence: John Kiley, Sr., Patrick Moran, John Brennan, Patrick Connors, Joseph Morrissey, James Kilbride, Anne O’Donnell, Mary Anne Quinn, Mary Connolly, Mary Burke, Bridget Bradley, Catherine Cushing, Thomas Regan, Mary Dowd, Mary O’Brien, Mary McCarthy, Rose Walsh, Mary Burns, Sarah McGuohan, Maria O’Sullivan, Annie M. Rafferty, Kate Reilly, Ann Mahon, Mary McGuinness, Rosanna Mulligan, Ellen McCavitt, Hannah Moriarty, Mary J. Sweeney, Ellen Ryan… The list extends for a couple hundred more names, three quarters of them obviously Irish in origin. Far more than half of them are women. Katherine O'Keefe O'Mahoney dedicated her life to promoting Irish pride. I have newspaper clippings of a lecture tour she did in 1911, about Ireland featuring numerous illustrations. She is billed as "a little woman with an enormous voice." Irish Legacy In the Catholic Church By focusing on their religion as a defining institution of being Irish, the Irish came to dominate the Catholic Church in America. “In 1880, the percentages of the clergy who were Irish American was 69 percent in the Archdiocese of Boston…Moreover, in 1886 thirty-five (51%) of the sixty-eight Catholic bishops in America were Irish born or of Irish descent. In 1920, it was still the case that two-thirds of Catholic bishops were Irish American, and in New England, that proportion was three-fourths.” (Source: American Catholics in the Protestant Imagination: Rethinking the Academic Study of Religion, by Michael P. Carroll, 2010) Later, when other Catholic immigrant groups followed - first the French Canadians, then the Poles, Italians, Portuguese, Lithuanians and (a few) Catholic Germans -- they found waiting for them a church that could provide something of a welcome, whereas the Irish basically had to create the Church in New England. Epilogue Since the early 1990s, many of the grand Catholic churches of the original Catholic communities of New England have been closed and often torn down. In Lawrence, this includes the aforementioned Immaculate Conception and St. Lawrence O'Toole, as well as half a dozen other churches. The same pattern was repeated in other urban centers: Lowell, Haverhill, Fall River, Worcester, Boston. I hope this and other blog posts will remind people that these abandoned churches were not just religious institutions, but were part of the physical culture of the immigrant groups who built them. Below: Today's St. Mary's church (Santa Maria de la Asunción)(source: church website)

13 Comments

6/11/2018 09:48:07 pm

Thanks for commenting on my blog and directing me here! Really well written, I look forward to reading more. I grew up in Lewiston/Auburn, when I moved to MA I lived in Lowell for a few years, and as a result of my childhood experience, one might say it was familiar territory. Sadly there's been a loss of church buildings there as well.

Reply

Nancy Greenwood

1/17/2020 10:13:09 pm

Hi, I grew up in Lawrence (60s-80) and really enjoyed your story. I am researching my French Canadian roots in Lawrence. My gr-gr-grandfather was a bricklayer in Lawrence around 1865. I enjoy reading snippets of other folk’s family stories. They run similar to mine as I unearth pieces. Not only did my great grandmother(mother’s side) use 2 different last names in Lawrence, I recently discovered my father’s father was the one who changed his name from Boisvert to Greenwood. My father never told us that. Your story gives me a glimpse of life while my ancestors were trickling in. Do you have other writings like this?

Reply

Carl McCarthy

12/3/2020 07:47:09 am

Thank you for reading this piece. Yes, I do have other writings - just have a look around my blog! There should be links to topics on the right. This link below should give you at least three articles I wrote on French Canadians, one about St. Anne's Church and other French-Canadian institutions in Lawrence; the other two about French Canadian institutions in Lowell, where they comprised a bigger percentage of the population than in Lawrence. https://www.ofaplace.com/home/category/french-canadian

Reply

Anne-Marie Nyhan-Doherty

3/17/2021 09:45:41 am

This article is wonderful. Thank you for a glimpse back at not only Lawrence's history but the Irish's as well. The Rev. James T. O'Reilly OSA Division 8 Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians was organized in May 1904. The first meeting took place in the Hibernian Hall at 280 Oak St., Lawrence, MA. Approximately 32 women attended and elected Katherine O'Keefe O'Mahoney as their first President. Today I serve as President of Division 8 Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians in Lawrence and come from very strong Irish roots (my Uncle was Mayor John Buckley) and proud to say that we are still ever-present within this community. Thank you for this wonderful background on our first LAOH President.

Reply

Jodi Linnehan Kriner

5/2/2021 08:52:39 am

Anne-Marie

Reply

Anne-Marie Nyhan-Doherty

5/2/2021 09:11:36 am

Hi Jodi, thank you for the kind comments. Of course I remember the Corrigans! I think they even lived in my neighborhood. I can see if we have any photos in the South Lawrence Library Irish Collection. It is not yet open but I can ask. I'll let you know. Thank you. Anne-Marie

Jodi Kriner

5/2/2021 09:22:15 am

Thanks Ann-Marie!! My aunts were proud Hibernians!! My uncles too (Joe Corrigan, Joe Conroy (actually, Anna's last name was Conway). Thanks so much!! Hi to all your kids!!

Cynthia Saba

3/18/2021 01:18:17 am

Growing up in Lawrence, I am the granddaughter of Irish immigrants and French Canadian immigrants. St. Mary’s was our parish and I attended St. Mary High School. I also attended Mass at St. Lawrence O’toole, as this church was close to our home. I enjoyed reading this. I take every opportunity to read about the history of Lawrence and the immigrants that built this great City!

Reply

Carl McCarthy

10/14/2021 10:26:37 pm

Thank you for stopping by. I hope you enjoyed the article. Thanks also for sharing some of your experiences.

Reply

Heidi Congistre

2/8/2022 04:16:00 pm

Hello and thank you for this blog. My great grandparents were married in 1907 by Chas M. Driscoll, Priest. Any relation to you? What was the date of the donors for the bell? My great grandma's name was on the short list given (Mary O'Brien). What was the date that James Trainor of Boston did the stonework (for St Mary's?). That is also a family name. I have the letter of discharge from the Civil War in May 1865 from James Trainor.

Reply

Carl McCarthy

3/17/2022 03:58:00 am

Thank you for your question. I’m not aware that father Charles Driscoll was my relative. I am related to father Daniel Driscoll of St Mary’s and St Augustine’s Lawrence. He was a priest until the 1950s He died in 1963.

Reply

Breda Alco4n

10/12/2023 11:07:48 am

My ancestors married in Lawrence in 1858. They were married by a James O Donnell who I think was an RC priest. I'd love to know what church they were married in and hope to look further into their time in Lawrence.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed