|

Native American History and Poetic License (a long read) Once upon a time, so the story goes, about 1628 – right when the English puritans were beginning to arrive to claim their promised land around Massachusetts Bay – there was a wedding of a native princess. She was the daughter of Passaconaway, the great Bashaba of the Pennacooks. The Pennacooks were the natives of the Merrimack Valley. Their domains extended from present day Haverhill all the way up to its headwaters along the Pemigewasset. The Bashaba made his home at a curve in the river, called Pennacook, site of present day Concord N.H. The tribe and affiliated bands of natives – Wachusetts, Agawams, Wamesits, Pequawkets, Pawtuckets, Nashuas, Namaoskeags, Coosaukes, Winnepesaukes, Piscataquas, Winnecowetts, Amariscoggins, Newichewannocks, Sacos, Squamscotts, and Saugusaukes – also met at prescribed times at various sites along the river, usually to fish: for example, at the falls at Amoskeag, later the source of waterpower for the mills at Manchester, N.H.; Pawtucket, later the source of waterpower for the mills at Lowell; and at Pentucket, later called Haverhill. According to a 1981 book on the Forgotten Salmon of the Merrimack, there were fourteen sets of falls on the mainstream of the Merrimack River, including on the Pemigewasset, where natives could have fished for salmon. The natives also met each year at the Weirs, fish traps designed to catch a bountiful harvest flowing out of swollen Lake Winnipesauke. This is where she met her groom, known as Ahquedaukenash (meaning "dams" or "stopping-places"). In the present day it’s called Weirs Beach. The groom was Montowampate, son of the “Squaw Satchem”, the female leader of the coastal Saugus Indians who took over when her husband Nanepashemet was killed battling their rivals, the Tarrantines, on August 8, 1619 in present day Ipswich, Massachusetts. How do we know any of this? From written records of English settlers mainly, and retellings of the story. The English settlers tell the stories of the Indians Passaconnaway and Sagamore James, as he was known to the English, were undoubtedly historical figures who signed deeds and, in the case of the latter, sought redress from English authorities to protect his interests and who is described as wearing English clothes. “Sagamore James went to Governor Winthrop on March 26, 1631, in order to recover twenty beaver skins of which he had been defrauded by an Englishman named Watts.” I hope to write more on the historical record left by natives in English colonial society, particularly the descendants of Nanepashemet who regularly tried to use the English courts to protect their land rights, in another blog entry. The first telling of the wedding story of this (yet unnamed) princess, daughter of Passaconaway, was by Thomas Morton, founder of the ill-fated Merrymount Colony. “The Sachem or Sagamore of Saugus made choice, when he came to man's estate, of a lady of noble descent, daughter to Papasiquineo [another name for Passaconnaway], the Sachem or Sagamore of the territories near Merrimack river, a man of the best note and estimation in all those parts, and (as my countryman Mr. Wood declares in his prospect) a great Necromancer; this lady the young Sachem with the consent and good liking of her father marries, and takes for his wife. Great entertainment he and his received in those parts at her father's hands, where they were feasted in the best manner that might be expected, according to the customs of their nation, with reveling and such other solemnities as is usual amongst them. The solemnity being ended, Papasiquineo causes a selected number of his men to wait upon his daughter home into those parts that did properly belong to her Lord and husband; where the attendants had entertainment by the Sachem of Saugus and his countrymen: the solemnity being ended, the attendants were gratified. Not long after the new married lady had a great desire to see her father and her native country, from whence she came; her Lord willing to please her, and not deny her request, amongst them thought to be reasonable, commanded a selected number of his own men to conduct his lady to her father, where, with great respect, they brought her, and, having feasted there a while, returned to their own country again, leaving the lady to continue there at her own pleasure, amongst her friends and old acquaintance, where she passed away the time for a while, and in the end desired to return to her Lord again. Her father, the old Papasiquineo, having notice of her intent, sent some of his men on embassy to the young Sachem, his son-in-law, to let him understand that his daughter was not willing to absent herself from his company any longer, and therefore, as the messengers had in charge, desired the young Lord to send a convoy for her, but he, standing, upon terms of honor, and the maintaining of his reputation, returned to his father-in-law this answer, that, when she departed from him, he caused his men to wait upon her to her father's territories, as it did become him; but, now she had an intent to return, it did become her father to send her back with a convoy of his own people, and that it stood not with his reputation to make himself or his men too servile, to fetch her again. The old Sachem, Papasiquineo, having this message returned, was enraged to think that his young son-in-law did not esteem him at a higher rate than to capitulate with him about the matter, and returned him this sharp reply; that his daughter's blood and birth deserved more respect than to be so slighted, and, therefore, if he would have her company, he were best to send or come for her. The young Sachem, not willing to undervalue himself and being a man of a stout spirit, did not stick to say that he should either send her by his own convey, or keep her; for he was determined not to stoop so low. So much these two Sachems stood upon terms of reputation with each other, the one would not send her, and the other would not send for her, lest it should be any diminishing of honor on his part that should seem to comply, that the lady (when I came out of the country) remained still with her father; which is a thing worth the noting, that savage people should seek to maintain their reputation so much as they do.” So when Thomas Morton “came out of the country” in 1629 (a euphemism for “getting expelled by puritans”), the bride apparently was still stuck up the Merrimack away from her groom, because nobody would escort her back down to Saugus. Later tellings of the story give her a definitive identity, Wenunchus. Alonzo Lewis, in his 1829 history of the town of Lynn (including Lynnfield, Saugus, Swampscott and Nahant, all of which were set off from Lynn), gives her this name… and also completes the story, sort of: “My lady readers will undoubtedly be anxious to know if the separation was final. I am happy to inform them that it was not; as we find the Princess of Penacook enjoying the luxuries of the shores and the sea breezes at Lynn, the next summer. How they met without compromising the dignity of the proud sagamore, history does not inform us; but probably, as ladies are fertile in expedients, she met him half way. In 1631 she was taken prisoner by the Taratines, as will hereafter be related. Montowampate died in 1633. Wenuchus returned to her father; and in 1686, we find mention made of her grand-daughter Pahpocksit.” Parts of the historical record of the English are very clear. According to the diary of John Winthrop, Montowampate and “almost all of his people” died of smallpox in September 1633. Below: Montowampate on the seal of the Town of Saugus, Massachusetts However, other historians have Wenunchus married to the younger brother of Montowampate, named Wenepoykin, a.k.a. Winnepurkett, called Sagamore George, who lived for many years, dying in 1684. Yet, even though he outlived his brother by half a century, his life was probably even more tragic. He was sold by the Puritans into slavery in Barbados in 1676 after being deemed a belligerent in King Phillips War...only to miraculously return like some lost prophet. After his return, he retired to Wamesit, the Praying Town for settled Indians, where he lived out his days, dying in 1684. As the recognized leader of the Saugus Indians and thus owner of the land from Salem to Saugus, immediately after his death the townspeople of Marblehead descended upon his “heirs”, including his elderly wife (not Wenunchus), obtaining a deed for their town on September 14, 1684. The deed was signed by Ahawayet, and many others, her relatives. She is called "Joane Ahawayet, Squawe, relict, widow of George Saggamore, alias Wenepawweekin." (Essex Reg. Deeds, 11, 132.) I suppose you can still go down to the land records office in Salem and look at her signature! The townspeople of Lynn and Salem soon followed suit, obtaining deeds from the heirs of Wenepoykin on September 4, 1686 an October 11, 1686 respectively. (Source: History of Essex County Massachusetts, 1888, by Duane Hamilton Hurd) But what if Wenunchus married Wenepoykin, not Montowampate, but also didn’t survive the shuttling between husband and father? This is the narrative tack taken, with some apparent poetic license, by one of the most famous poets of the mid-nineteenth century, and certainly the most famous poet until Robert Frost to be claimed by the lower Merrimack Valley region. (Robert Frost being claimed, rather surprisingly, by Lawrence because he graduated from Lawrence High School.) I am talking about John Greenleaf Whittier. The Story of Wenunchus in the Hands of John Greenleaf Whittier John Greenleaf Whitter was born on an ancient farm in Haverhill in 1807. It was built by his first Whittier ancestor in Haverhill almost a 150 years earlier. Although Whittier was self-educated, by the time he died in 1892, he was the author of one of the most famous poems of the day, Snowbound. This long piece, published in 1866, describes being stuck in the farmhouse on a snowy day, and it made him well-off financially. He ran in literary circles, mainly on account of being mentored in his younger days by an earlier publisher of his works, William Lloyd Garrison, in Garrison’s Newburyport newspaper. Garrison introduced him to the abolitionist cause, and to many literary lights of his day. Through these connections and the recognition he received for Snowbound, the self-educated Whittier received an honorary degree from Harvard in 1877. For his entire life, except for a spell of about three years working in New York and Philadelphia, he barely left the Haverhill-Amesbury-Newbury area. When Whittier did finally manage to see a bit of the world, it was mainly just places like the White Mountains and the Isles of Shoals. Whittier’s extreme provincialness, despite his involvement in the abolitionist movement and his honorary Harvard degree, is to me what gives his poems their authenticity. He is, to me, the voice of the historic lower Merrimack Valley. Snowbound is not just about being stuck indoors on a snowy day, it is about Haverhill and its history and setting. And one of his earlier epic tales, the Bridal of Pennacook, which tells the tale of Wenunchus and her marriage to [in Whittier’s version] Wenepoykin, whom he calls Winnepurkit, the poem is a vehicle for glorifying the entire Merrimack River, from the coastal sand dunes right up to the river’s highest headwaters. About his poem, “The Bridal of Pennacook” The poem was apparently written in 1844 but not included in any book of poetry for many decades. It is long – twenty five pages. It employs a conceit that the poem is composed spontaneously for entertainment by five hikers staying in a lodge near Mount Washington while the youngest of them recovers from her cold. The five characters who together compose the poem for their entertainment are the narrator, a writer and a poet; a city lawyer, “Briefless as yet, but with an eye to see /Life's sunniest side, and with a heart to take/Its chances all as godsends”; his brother a student training to be a minister, “as yet undimmed/By dust of theologic strife, or breath/Of sect”; a shrewd sagacious merchant, “To whom the soiled sheet found in Crawford's inn, /Giving the latest news of city stocks/And sales of cotton, had a deeper meaning/Than the great presence of the awful mountains/Glorified by the sunset”; and the merchant’s lovely young daughter, “A delicate flower on whom had blown too long/Those evil winds, which, sweeping from the ice/And winnowing the fogs of Labrador.” Whittier thus sets the scene: So, in that quiet inn Which looks from Conway on the mountains piled Heavily against the horizon of the north, Like summer thunder-clouds, we made our home And while the mist hung over dripping hills, And the cold wind-driven rain-drops all day long Beat their sad music upon roof and pane, We strove to cheer our gentle invalid After the lawyer tells her stories of his (mis)adventures fishing in the Saco River, and the divinity student, “forsaking his sermons”, recites poems to her from memory, the narrator rummages through the musty book collection at the inn, where he finds “an old chronicle of border wars and Indian history.” From this book the narrator reads aloud a summary of the story of Wenunchus and Montowampate, except in this version she is called Weetamoo (actually the name of a wife of a prominent native chief in Rhode Island) and, instead of marrying Montowampate, she marries that man’s brother Wenepoykin, whom he calls Winnepurkit. Our fair one [i.e. the girl], in the playful exercise Of her prerogative,—the right divine Of youth and beauty,—bade us versify The legend, and with ready pencil sketched Its plan and outlines… The self-taught Whittier tries to show his knowledge of classical Greek poetical forms, which I suppose was de rigeur for professional poets of the era. He does not say which character “versifies” which part of the Wenunchus story, but it might be possible to hazard a guess based on their supposed personalities. In the first section, the poem sets the scene, describing the pre-contact Merrimack River itself, “ere [before] the sound of an axe in the forest had rung, Or the mower his scythe in the meadows had swung.” This section is in so-called Alexandrine meter, twelve syllables per line with a stress on the sixth and last, in simple A-A B-B rhyme. Among other things, it takes the listener through the geographic features of the river: “Amoskeag's fall”, the “twin Uncanoonucs” stately and tall, the Nashua meadows green and unshorn, etc., all before “the dull jar of the loom and the wheel,/The gliding of shuttles, the ringing of steel” had invaded the river in the form of mills and waterworks. In the next section, the poem describes the stern character of The Bashaba, i.e. the great chief Passaconaway, in a more complex format: paired quatrains, rhyming aaab cccb, with 7-7-7-5 syllables, while the first stanzas are longer, nine lines for the first, ababbaddd. The character telling this section – the lawyer, perhaps? – weaves a tale of the awe inspired by Passaconaway: Here the mighty Bashaba Held his long-unquestioned sway, From the White Hills, far away, To the great sea's sounding shore; Chief of chiefs, his regal word All the river Sachems heard, At his call the war-dance stirred, Or was still once more. In the third section, the poem describes The Daughter, Weetamoo. The description focuses on her mother’s death giving birth to her (a detail certainly conjured up with poetic license), and the joy she ultimately brings to her stern old father, who decides not to take another wife. The meter and rhyme for this section is rather simple, likely the work of the merchant character; for the rest of this blog piece I’ll refrain from detailing the rhyming scheme of each section. The fourth section describes The Wedding itself: The trapper that night on Turee's brook, And the weary fisher on Contoocook, Saw over the marshes, and through the pine, And down on the river, the dance-lights shine. For the Saugus Sachem had come to woo The Bashaba's daughter Weetamoo, The fifth section describes Weetamoo’s New Home with her new husband, in the coastal marshes of Saugus far from her mountain homeland. Whoever tells this part of the tale is rather uncharitable about the coastal terrain of Essex County: A wild and broken landscape, spiked with firs, Roughening the bleak horizon's northern edge; And later, an equally dreary scene, it is contrasted with the mountain home of Weetamoo: And eastward cold, wide marshes stretched away, Dull, dreary flats without a bush or tree, O'er-crossed by icy creeks, where twice a day Gurgled the waters of the moon-struck sea; And faint with distance came the stifled roar, The melancholy lapse of waves on that low shore. No cheerful village with its mingling smokes, No laugh of children wrestling in the snow, No camp-fire blazing through the hillside oaks, No fishers kneeling on the ice below; Yet midst all desolate things of sound and view, Through the long winter moons smiled dark-eyed Weetamoo. There is an oblique reference to Weetamoo's sexual awakening as a wife ("o'er some granite wall/Soft vine-leaves open to the moistening dew"). However section ends with her husband sending her back home to assuage her homesickness, escorted by soldiers: Young children peering through the wigwam doors, Saw with delight, surrounded by her train Of painted Saugus braves, their Weetamoo again. The sixth section describes her time back at Pennacook, at first enjoyable but then fraught with anxiety when her husband does not summon her back: The long, bright days of summer swiftly passed, The dry leaves whirled in autumn's rising blast, And evening cloud and whitening sunrise rime Told of the coming of the winter-time. But vainly looked, the while, young Weetamoo, Down the dark river for her chief's canoe; No dusky messenger from Saugus brought The grateful tidings which the young wife sought. The clash of egos between her father and her husband overtakes the situation and she is forced to spend the winter up in Pennacook. The section ends with her fixing to leave as soon as the river thaws, by herself, down the Merrimack. The seventh section, the Departure, describes her planning then and her actual flight. The river is swollen with rain and snowmelt, full of iceflows. At first, she appears to be managing despite the danger: Down the vexed centre of that rushing tide, The thick huge ice-blocks threatening either side, The foam-white rocks of Amoskeag in view, With arrowy swiftness sped that light canoe. However, things start to go wrong: The small hand clenching on the useless oar, The bead-wrought blanket trailing o'er the water… It ends dramatically: Sick and aweary of her lonely life, Heedless of peril, the still faithful wife Had left her mother's grave, her father's door, To seek the wigwam of her chief once more. Down the white rapids like a sear leaf whirled, On the sharp rocks and piled-up ices hurled, Empty and broken, circled the canoe In the vexed pool below—but where was Weetamoo? The final section of the poem, the Song of Indian Women, is a coda of sorts, sang by “the Children of the Leaves beside the broad, dark river's coldly flowing tide.” The Dark eye has left us, The Spring-bird has flown; On the pathway of spirits She wanders alone. The song of the wood-dove has died on our shore Mat wonck kunna-monee! We hear it no more! You can read all of The Bridal of Pennacook by John Greenleaf Whittier online. The poem should be read out loud for its full impact. I tried to do just that. You can watch my efforts reading the entire poem (which takes about an hour) at these videos below. Someday I’d like to replace the awkward video images of my contorted mug reading, with a slide show of the New Hampshire landscape to accompany the poetry. Poetic license and appropriation of “other people’s stories” John Greenleaf Whittier applied poetic license to the story handed down by Morton and others. He embellished it and added details for dramatic effect. Should he be telling the story of Wenunchus at all? Current cultural sensitivities caution against “cultural appropriation.” Because Whittier was not a Pennacook Indian, should he be writing poetry about Pennecooks? How about the fact that he sets up the poem around discovery of “an old chronicle of border wars and Indian history”? Does this make the poem about something likely to be found in old New England of the 1840s, when the memory of French and Indian wars was fresher, and the sight of actual Native Americans along the Merrimack could still be something of living memory? And what if there are no Pennacooks left to tell the story? Can someone else tell the story? Should only native Americans tell the story? Some natives were enemies of the Pennacooks. For example, the Mohawks were fierce warriors who would raid Pennacook lands periodically from beyond the Hudson River and steal their grain stores. A huge battle between Mohawks and Pennacooks apparently occurred in 1615, when the Mohawks attacked Pennacook itself. Other tribes with which the Pennacooks sometimes battled included the Abenaki and the Taratines. I would argue that the inheritors of these tribes, some of which still exist, have no direct claim to the stories of the Pennacooks. Do the current inhabitants of the Merrimack Valley region have a right to appropriate the stories of the Pennacooks? It is probably true that the settlement by the English starting in 1620, and the diseases they brought, followed by war and appropriation of land, led to the extinction of the Pennacooks. Does that mean the descendants of actors in the 1600 and 1700s are barred from telling these stories? How about the fact that many “tribes” arrived in the Merrimack Valley only after the Pennacooks were long-extinct: the Irish, the Italians, the French-Canadians, the Dominicans, the Puerto Ricans…do they have less or more of a right to tell these stories about the history of their present-day land? My own belief is that artists can interpret any story, and whether it is offensive or not depends on specific presentation. It is never categorical based on some construct of the artists “tribe” versus that of his subject matter. The poetry of John Greenleaf Whittier is largely forgotten, even among people who read poetry. A lot of it is sentimental and cliched, and comes across as long-winded and maudlin to me. But within his oeuvre, there are nuggets everywhere about the Merrimack Valley and his home. People can get reacquainted with the old stories of their home, simply by reading his works. The Bridal of Pennacook is one story that is worth retelling. Maybe someday it will be turned into a musical?

2 Comments

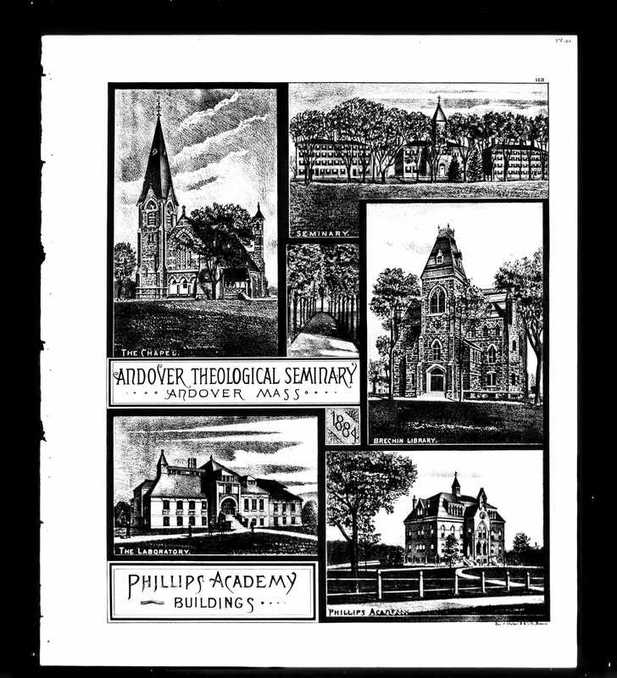

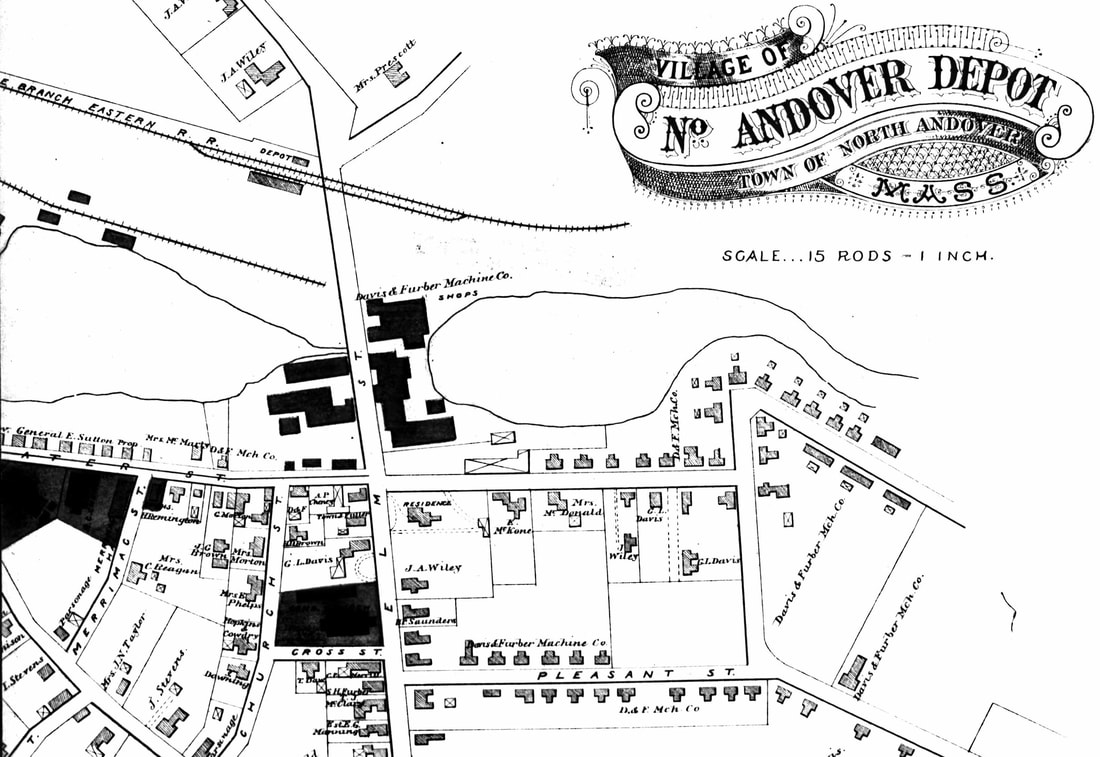

(A Long Read) Above: the South Parish Church, Andover, Massachusetts. The current church is the fourth meetinghouse built on the site. Photo by the author. Around the year 1800, a battle began over culture and tradition in the old town of Andover, setting the northern part of the town against the southern part. On the northern side was progressive, liberal enlightenment thinking that came to dominate the more educated classes of eastern Massachusetts in the nineteenth century; on the southern side were old New England traditions that were in danger of being lost. The split was arguably hastened by the much more significant industrialization of the North Parish by the 1840s, with large mills clustered around Cochichewick Brook and a growing area of worker housing, Machine Shop Village adjacent to newly-formed Lawrence; versus the less-industrialized South Parish. In many ways the conflict found in this one town, Andover, encapsulated the competing cultural trends of the first half of the nineteenth century of Massachusetts: Enlightenment versus Puritan; Urban versus Rural. These days, most people seem to be unaware of the somewhat tortured history that led to the separation of North Andover, which is actually the oldest part of the town, from Andover. Brief history of Andover’s parishes The town of Andover was founded in the early 1640s at the tail end of the original Puritan settlement that accompanied the Great Migration. See the Glossary. For many decades after original settlement, the town of Andover stood along the north-western frontier of settlement in Massachusetts, along with its then-near-twin on the northern bank of the Merrimack River, Haverhill. A few miles beyond the northern bank of the Merrimack was wild, forested country inhabited only by native Americans. The first settlement in Andover occurred at the present-day North Andover common, the oldest part of then-Andover. In addition to establishing a meetinghouse and hiring a minister from Harvard – the source of virtually all puritan ministers – a schoolmaster was appointed to teach reading, writing and arithmetic (required by Massachusetts law from 1642 onward). A common was laid out and house lots were provided nearby for convenience and for mutual protection against potential Indian raids. Farm lands were allocated to residents on the periphery of the town. After the original settlement, few houses were built on the common and all further residences were built closer to allocated farmland. Despite the original settlement of Andover in the 1640s near Cochichewick Brook, the population continuously shifted southward. In 1697, upon the death of Andover's second minister, the town agreed in principle to build another meetinghouse that was more convenient to more of the population. After a decade of dispute over proper location, the General Court of Massachusetts became involved, and a "South Parish" was "set off", meaning that, henceforth, residents in the larger, southern part of the town would be assessed separately in support of their own minister and meetinghouse. That first South Parish church was erected slightly to the east of the present-day South Church, while the North Parish built its own new meetinghouse on basically the same location as the previous North Parish meetinghouse. The two Andover parishes then co-existed uneventfully for a century. Such "setting off" was the ordinary course of things. The town of Haverhill, which at that time was enormous compared to Andover, had set off three additional meetinghouses and parishes by 1744 while remaining one town (with the exception of the creation of Methuen in 1725). Despite a history of harmony, however, starting around 1800, a number of social and economic currents ultimately drove the two Andover parishes apart, into near diametric opposition. After half a century of estrangement, they finally divorced in 1855, with the South Parish (plus its recent offshoot the West Parish) taking the name of Andover in exchange for a $500 payment; and the North Parish becoming the town of North Andover. Here is the story of that break-up. New England Congregationalism in the Age of Enlightenment The period following the American Revolution (and arguably all of the eighteenth century) was the Age of Enlightenment. Prominent thinkers, from Voltaire and Montesquieu in France, to David Hume and Adam Smith in Scotland, had shaped the Western intellectual landscape that hitherto had been dominated by theologians. Mankind grew confident in its ability to shape its own destiny, through rational thought and technology. According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “the expectation of the age [was] that philosophy – in the broad sense of the term, which includes the natural and social sciences – would dramatically improve human life.” In New England, Enlightenment thinking shone through the prism of the American Revolution. “Eighteenth century Rationalism under the influence of English philosophers like John Locke became the basis for new religious thought in the same way it had helped free America’s spirit of political independence. Locke defended individual liberty and equality and defended human rights. By 1805, Arminians had revamped Christian theology to conform with the principles of the Age of Rationalism.” From And Firm Thine Ancient Vow: The History Of North Parish Church of North Andover, 1645-1974, by Juliet Haines Mofford (1974). Who were these “Arminians”? In the context of the established congregationalist churches of Massachusetts, these were ministers and their followers who had rejected the harsh predestination of their puritan forbears, as taught by reformation leader John Calvin (hence Calvinism or Calvinist). Instead, they espoused the views of Jacobus Arminius. He was a Dutch reformation leader who had opposed the views of Calvin. We are not chosen to believe, he said (contrary to the Calvinist notion of “the elect”), but instead, all humans are given the power to believe in order then to be chosen by God *if* they chose to believe. Christ furthermore died to save all people, not just the elect, and in fact may not have been divine. (This led to the label “Unitarian” from critics, who wanted to uphold the Trinity of the godhead, Father, Son and Holy Spirit.) Some commentators viewed this shift as a natural consequence of the American revolution. “Most Arminian ministers were staunch Federalists and strong supporters of the politics of Washington and John Adams. Many ministers saw in Washington a symbol of national unity possible under the hand of God’s providence and guidance, and they said so in sermons.” (Again, quoting Moffard.) The Unitarians Begin to Dominate “The thoughtful men who represented the Liberals…were few in number at first and with few exceptions lived under the shadow of Beacon Hill or nearby.” (meaning they were your typical Boston rich liberal elites, I guess) (quoting The History of the Andover Theological Seminary, by Henry K. Rowe (1933)). However, by 1800, Boston’s Congregationalist churches had gone solidly Unitarian, with only two out of fourteen maintaining traditional Calvinist ministers. This led to the formation of Park Avenue Congregationalist Church, so-called Brimstone Corner, which reverberated with Calvinistic sermons about the utter depravity and damnation of man. The thunderbolt for the traditionalists, however, was the fall of Harvard to the Unitarians. Prior to 1800, Harvard college was essentially a training ground for all Massachusetts ministers. All students were a classical education deeply focused on reading of original texts in Greek, Latin, Hebrew and Aramaic, regardless of whether they went on to become ministers. The times they were a’ changing, however. “The tendency of the period was to introduce other studies in place of the older discipline, as science and modern literature became more popular in learned circles than Hebrew and Greek.” In short, in higher education, “Theology lost its position as queen of the sciences.” So, “when Reverend Henry Ware of Hingham was elected to the Hollis professorship of divinity at Harvard College in 1805, New England Congregationalism felt the shock, for it was well understood that Ware was really a Unitarian, and that at Cambridge his influence would be radical.” (All quoting Rowe). The Merrimack Valley is the epicenter of the Calvinist response – Andover and Newbury factions The strongest responses anywhere in Massachusetts to the fall of Harvard to the Unitarians seem to have come from Calvinist luminaries in Andover and in Newbury. “Dr. Eliphalet Pearson was disturbed gravely by the liberal trend at Harvard. Pearson was one of the outstanding men of the time in educational circles. He had been the first principal of Phillips Academy and had established its reputation, and after eight years he had been elected to a professorship at Harvard.” (Quoting Rowe.) Phillips Academy, located on a hill in Andover’s South Parish and chartered 1778, was in many ways just another typical “academy” found across that region at that time: a secondary school focused on advanced education for older boys, and sometimes girls, in order to further train them beyond the Three Rs of the schoolhouse –and, in the case of boys, prepare them for the rigors of Harvard. Governor Dummer’s Academy in the Byfield section of Newbury was the precedent for all of these academies of the lower Merrimack Valley, being the alma mater of Samuel Phillips, founder of Phillips Academy. Other similar academies could be found in Groton (now called Lawrence Academy, which for decades also educated girls), Haverhill (the “Haverhill Academy”, the first academy to accept girls, merged with Haverhill High School in 1841), and even in the North Parish of Andover (“Franklin Academy” which closed around 1845 – more on that below). However, from the early days, Phillips Academy did apparently stand out in terms of its academic rigor. “When [Pearson] failed to stem the tide of liberalism [at Harvard] in 1805, and then when Professor Webber was chosen president the next year, Pearson resigned his office and went back to Andover, convinced that something needed to be done to defend orthodoxy. The Academy, of which he was a trustee, cordially welcomed his return and gave him a year's rental of a new house nearby. Then he began to plan for the establishment of a theological institution which should maintain the doctrines of the fathers of New England against the threatening apostasies of the times.” (Quoting Rowe) Meanwhile, downriver in Newburyport, similarly minded leaders were meeting. Technically they were “Hopkinsonians” with slightly less Calvanistic views than Pearson and his cohorts on Andover hill. “Their leader was Dr. Samuel Spring, minister at Newburyport. He had been a pupil of both Hopkins and Bellamy, and had been a recognized leader in eastern Massachusetts for forty years. Leonard Woods, a young minister at West Newbury, was his close friend. Through Spring and Woods three laymen were aroused to an interest in theological education. These were William Bartlet [one t], a successful merchant of Newburyport, Moses Brown of the same town, and John Norris of Salem. They were all men of wealth, and though not all church members they were willing to use their money for religious purposes, and they soon agreed to support the plans for a theological school at West Newbury.” Why was the orthodox response to the Unitarians focused in the lower Merrimack Valley? My theory is that the region had the goldilocks location of not-too-much, not-too-little: on the one hand, it was still part of the original Puritan heartland settled by the Great Migration, and therefore of enough significance to have cultural sway over much of New England, unlike the frontier areas of New Hampshire and western Massachusetts that were still being cleared; yet, on the other hand, it was peripheral enough not to have fallen completely under the cosmopolitan influence of turn-of-the-nineteenth-century Boston, which was increasingly becoming a global port through which flowed the wealth of international trade via world-renowned Yankee merchant ships. Below: Andover Theological Seminary 1884 Founding of the Andover Theological Seminary After significant negotiation, the Pearson wing and the Woods wing agreed to form a theological seminary in Andover next to the site of Phillips Academy, sharing the same Board of Trustees as the academy. Because the two factions could not agree on the wording of their creeds, there were two sets of founding documents for the Andover Theological Seminary, one for the orthodox Calvinists and one for the Hopkinsonians. They were however unified in their antipathy toward Unitarians. On the orthodox side, it was provided that every professor must at the time of his inauguration solemnly promise to maintain and inculcate the Christian faith as summarily expressed in the Shorter Catechism [a standard statement of belief of early puritans] "in opposition not only to Atheists and Infidels, but to Jews, Mahommetans [i.e. Muslims], Arians, Pelagians, Antinomians, Arminians, Socinians, Unitarians, and Universalists, and to all other heresies and errors, ancient or modern, which may be opposed to the Gospel of Christ, or hazardous to the souls of men." Furthermore, every professor must repeat this declaration in the presence of the Trustees once in five years. Getting the Hopkinsonians on board was important because of the wealth they brought. The main building was named Bartlet Hall in gratitude for the gift of their main benefactor (it exists today on the campus of Phillips Academy and has been renamed Pearson Hall). The Hopkinsonians were thus allowed to have Associate Statutes that existed alongside the institution’s charter documents, and every occupant of a chair endowed by the Hopkinsonians “should be a Hopkinsonian.” “The establishment of the Seminary was a significant event in American church history. The union of the two theological groups of conservatives in the Seminary proved an effective counterpoise to the Unitarian trend in Congregational circles. Naturally the Liberals were not pleased. The Harvard attitude was not friendly. Woods reported to Farrar in 1807 that there was ‘loud murmuring and reproach and imprecation.’” (Rowe) “ANDOVER [Theological Seminary] was founded for the distinct purpose of preparing men for the parish ministry. At that time the prestige of the Trinitarian Congregationalists was at stake. The Unitarians had the advantage of Harvard instruction and the Harvard reputation. Unless the Trinitarians could establish a theological school that would attract young men of ability, and year after year could supply the Congregational churches with orthodox leaders who were able to measure swords successfully in doctrinal controversy when need arose, they would be worsted in the competition of the two theological parties.” It should be noted that, “in a legal sense the new Seminary at Andover was the theological institution in Phillips Academy, but it was so distinct in faculty, buildings, and funds as to be actually a separate school.” (Rowe) “It soon eclipsed Phillips Academy in endowment, buildings, and reputation. A few years after its founding, it included two large brick dormitories--the present Foxcroft and Bartlet Halls—with a chapel and recitation building...In addition, a number of homes had been constructed for the Seminary professors, the most im pressive being the present Phelps, Pease, and Stuart houses. By contrast, Phillips Academy had one wooden classroom building and a modest house for its principal.” (From Youth from Every Quarter: A Bicentennial History of Phillips Academy, Andover by Frederick S. Allis, Jr. (1979)) In sum, the essential institution for defending orthodox congregationalism was founded on a hilltop in the southern part of Andover, which some in the North Parish of Andover then called “Brimstone Hill.” The Seminary – the first school in America for training ministers that was not part of a college – was technically in the South Parish, but had its own independent congregationalist church. The Seminary exercised significant sway over the philosophy of the nearby South Parish church, and then the West Parish church, which was set off from the South Parish in 1824. Both were avowedly Trinitarian (and thus, at the time, Anti-Unitarian). They are still Trinitarian, to the extent such distinctions are relevant in modern society. Meanwhile, the North Parish of Andover was going in a very different direction As you might have guessed, the members of the North Parish generally considered themselves more forward thinking and enlightened. The South Parish handbook of 1859 went out of its way to label an early North Parish minister, Reverend William Symmes, who was ordained in 1758 and died in 1808, as an “Arminian” although such label is debatable. Another historian of the region, Sarah Loring Bailey in her 1880 history of Andover, called Symmes “the last of the old-time ministers.” It is definitely true that when a new minister was sought for Andover’s North Parish in 1809, being too Calvinist led to a rejection. “When, after the death of Dr. Symmes, the parish came together to ordain the minister whom they had called, the Rev. Samuel Gay, it proved that the views of Christian doctrine which he expressed were not satisfactory to all the officers of the church and parish, being more rigidly Calvinistic than they approved. The ordination services were, therefore, broken off.” (Quoting Bailey) Instead, they hired Reverend Bailey Loring who was ordained on September 19, 1810, age twenty-three. Interestingly, he was a graduate not of Harvard but of Brown. Of the four colonial era colleges in New England, Brown was an outlier in that, from its inception, it allowed different religious views (although, having been founded by Baptists expelled from Massachusetts, it was required until 1950 to have a Baptist minister as its president). In my research of the various meetinghouses of the lower Merrimack Valley going back to the 1630s, I have never come across a minister educated at Brown, although two were educated at Yale and one at Dartmouth (other congregationalist stalwarts). Dozens if not hundreds of ministers in Massachusetts prior to 1800 were educated to Harvard. “Mr. Loring was not a Calvinist. His theological education had been under the Arminian school of belief. But, like his predecessors, he was catholic [meaning universal not Roman Catholic] in his sympathies, and maintained throughout his ministry friendly relations with his brethren of various creeds. He continued to exchange pulpits with those of similar tolerant principles, even after the partition walls had been built up between the two divisions of the Congregational order, and when this breaking through was censured by the more dogmatic of both parties.” (Quoting Bailey) He did, however, establish a new covenant between members, one of distinctly Unitarian beliefs. Some supporters of the North Parish side of the story saw a conspiracy against him coming out of the Seminary and the South Parish. Ms. Moffard notes in her 1974 history of the North Parish church that Loring was rejected from the Andover Seminary for incompatible beliefs, and this fact “weighed in Mr. Loring’s favor” when he was ordained by the North Parish. “Bailey Loring was their man, an unmistakable and irrepressible Arminian who was undaunted by the proximity of the new seminary in South Parish.” (quoting Moffard) “The schism began, possibly as early as 1820, when certain members felt that Mr. Loring and North Parish were not satisfying their soul yearnings…they held the belief, not only in Jesus of Bethlehem, a historical teacher [the classic Unitarian view which, by the way, in my book is no longer Christian per se], but in Jesus the Christ, Lord and Savior…Students from the Seminary were often present to lead them in worship.” (Moffard) Eventually, a Trinitarian faction was able to form in North Parish, apparently aided by the Theological Seminary. Their situation was greatly aided by the 1833 disestablishment of the Congregational churches in Massachusetts, which meant that, henceforth, financial support could not come from the parish poll tax; rather, churches had to be dependent on their members, who could live wherever they wanted. On July 24, 1834, the Trinitarian Calvinistic Church was formally organized. On September 3, 1834 the new building was declared. It could be viewed as a mission church from the South Parish: of its members, only one male member was a defector from the North Parish, while 14 came up from the South Parish. This church changed its name to Trinitarian Congregational Church in 1841, and bears that name to this day. The Unitarians in North Parish engaged in no such missionizing, and for the entire 19th century, Andover’s South and West Parishes had no Unitarian church, presumably being under the sway of the Theological Seminary. The existing Unitarian-Universalist church in Andover moved there from Lawrence in 1964. Below: Interior of North Andover’s Trinitarian Congregational Church, built 1865 by the same architect as the 1861 Andover South Parish Church (source: church website) The Cultural Differences Between North Parish and South Parish Illustrated by a Comparison of Academies Pages could be written about the strict, cold demeanor of Phillips Academy and the Andover Theological Seminary. The following gives a flavor of life as a student at the Theological Seminary. Life at the Academy was not that much different apparently. “For exercise the students blasted and cleared away rocks from the Missionary Field back of the buildings, worked on the campus grounds, and rambled about the vicinity. Two students, one of whom became a well-known college professor, used to race each other around a three-mile triangle on winter mornings before sunrise to give tone to breakfast and the day's work. Professor Park, when a student at Andover, arose at 4.30 and walked with another student over Indian Ridge or through Carlton's Woods, practising elocutionary exercises in order to develop his oratorical powers.” (Rowe) The author notes rather dryly “The students do not seem to have been miserable, perhaps because they were seldom idle.” Here is a letter from one Andover student in 1819: “That you may know how much a slave a man may be at Andover, if he will follow the rules adopted by the majority, I will give the order of the day. By rising at the six o'clock bell he will hardly find time to set his room in order, and attend to his private devotions, before the bell at seven calls him to prayer in the chapel. From the chapel he must go immediately to the hall and by the time breakfast is ended, it is eight o'clock, when study hours commence and continue till twelve. Study hours again from half past one to three. Then recitation, prayer, and supper, makes it six in the afternoon. Study hours again from seven to nine leave just time enough for evening devotion before sleep.” Meanwhile, the North Parish had its own academy, the so-called Franklin Academy. It can hardly be more different than Phillips Academy, yet in its heyday it seems to have attracted students from as far and wide as Phillips Academy. “In 1799, Mr. Jonathan Stevens gave land on the hill north of the [North] meeting-house. Subscriptions were made by some of the principal citizens. The academy also received a fund of a little more than eight hundred and seventy-five dollars from the division of the proprietors' money [each of Andover and Haverhill and successor towns such as Methuen had rights obtained from the original settlers, the so-called Proprietors, who had paid money for the deeds from the Indians; by the eighteenth century, it was a separate fund that was slowly depleted as the last of the proprietor land was sold off]. The academy was built in 1799. It had been provided that the school should be for both sexes, and it was the first incorporated academy in the State where girls were admitted. The academy was built with two rooms of equal size, — the north room for the male department, the south room for the female department. A preceptor and preceptress had charge respectively of the two departments.” “The school was incorporated in 1801 as the North Parish Free School, and in 1803, by act of the General Court, the name was changed to Franklin Academy. This school, though now discontinued, had a flourishing life of more than fifty years, and numbered among its members students from more than a hundred different towns, a dozen States, and several foreign countries…”(in other words, on par with Phillips Academy of the time.) “Two manuscript records have been found, one containing the names of the male students from 1800 to 1802, and from 1811 to 1834, the other the names of the female students from 1801 to 1821. The names of the preceptors are nowhere found recorded, and the recollections of the pupils and residents of the town in regard to them are indistinct and often conflicting. The following are such facts as the means of information supply: The first Preceptor was Mr. [presumably the Rev. Micah] Stone, of Reading, a graduate of Harvard College 1790, tutor 1796, student of theology with Rev, Jonathan French, Andover, settled 1801 at Brookfield. Mr. James Flint (Rev. Dr. Flint, of Salem) was Preceptor, 1800-1811.” The student experience at Franklin Academy contrasts markedly with the Calvinistic south parish and Phillips Academy: “The reminiscences of the few who yet remain of the early students of Franklin Academy, are of delightful days. The notions of propriety in the North Parish were then much relaxed from the rigidity of Puritan customs, and many social recreations were permitted to the young folks. These festivities the elders directed and shared.” The Franklin Academy ultimately went out of business, it was said, because North Parish – soon to be North Andover – started providing decent town-led secondary education in the form of a High School. This was also the fate of Haverhill Academy, another early academy. It is not surprising that in liberal North Parish, universal secondary education should become provided for by the town and not by private means. Below: North Andover Depot, 1884 showing Davis & Furber facilities on the Cochichewick Brook. Note the Trinitarian Congregational Church at Cross & Elm The Split The actual split into two towns did not happen until 1855, when the matter was put to a vote. South Parish paid North Parish $500 to use the name Andover, despite North Parish being the original part of Andover. By the time of the split, North Andover had become significantly industrial. Four significant industrial concerns clustered around Cochichewick Brook: North Andover Mills, Scholfield Mills, Sutton Mills and Davis and Furber Machine Company. This area of North Parish was in some ways an appendage of Lawrence. There was even discussion of the entire North Parish becoming part of Lawrence, then a booming industrial city full of promise and on the up-and-up (and in 1877 a small section did become part of Lawrence). It is indicative that, whereas the Machine Shop in North Andover was already connected to Lawrence by public street trolley in 1868, there wasn’t a trolley to Andover until the 1890s, the peak of trolley construction when trolleys ran to every neighboring town. (Source: Maurice Dorgan’s Concise History of Lawrence, 1918). “Though the south village of Andover remained unchanged, the industries of North Andover and the mills of Lawrence were so near that her citizens could not remain oblivious to the changes that were taking place. With a rapidly increasing population, New England was sending her sons to the West to be pioneers like their colonial ancestors, and home mission societies were organizing to take care of their religious needs. [See my review of Yankee Exodus.] The application of steam to railway and river travel facilitated the movement of the population, and people became less provincial as their contacts widened.” Supposedly, the split was led by members of the South Parish. They have wanted to keep their relatively rural, traditional idyll untainted by the newfangled ideas and newfangled megaindustry that typified the North Parish. A description of Andover Hill written in 1856 by a student reflects the desire to maintain the rural idyll despite the encroachment of industry and change: "To the north the eye can travel up to the blue hills of New Hampshire, and only three miles distant stand and smoke the mammoth factories of the city of Lawrence. The whole scenery about is dotted with sequestered villages and snow-white farmhouses. Lowell, Salem, Haverhill, and Boston, are next-door neighbors. On the south is a hedge of railroad; on the east we can almost hear the roaring of the ocean; on the north flows the devious but busy Merrimac; while the west, to say nothing of its home associations, gives us a never-to-be-forgotten sunset. Thus environed, overarched by a deep blue sky, and standing upon ground whose beauty pen and paper cannot paint, Andover is the spot for a seminary. . . . Nearly every house looks like a countryseat, and even the old edifices, which were raised, I suppose, in the last century, have an air of neatness about them, being clothed in the purest white. It is a very wealthy place; but the wealth of the Seminary astonishes me. Nearly every house within a quarter of a mile is owned by the Trustees." Legacy of the Andover Theological Seminary By 1908 when the Andover Theological Seminary departed from Brimstone Hill in south Andover for Cambridge, leaving Phillips Academy to fend for itself again, the world was completely different from when it was founded a century earlier. Both forms of congregationalist religion were dissipated, Unitarian and Trinitarian, as competing protestant denominations planted their roots in New England; and then as Boston elites started defect en masse to the Episcopalians, perhaps conflating their Yankee roots with Englishness and forgetting that the Anglican Church had been the scourge of the puritans. The Seminary itself suffered scorn and mockery in the Boston papers for engaging in a sort of theological purity test for Professors in the 1880s. Its heyday was the period from 1808 to the Civil War. When it merged into the Harvard Divinity School (ironically) it only had three students. Yet it left a gigantic legacy on the intellectual landscape of America, because of the tendency of traditional Congregationalists who migrated out of the puritan heartlands of New England (see my entry on the Yankee Exodus) to establish colleges…and their desire to have intellectually rigorous Andover Seminary men as presidents of those colleges. “It is impressive to call the roll of colleges that invited Andover [Seminary] men to be their presidents. In New England they include Bowdoin and Dartmouth, Middlebury and the University of Vermont in the northern tier of states; Amherst, Smith and Brown in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. In New York were Hamilton, Union, and Vassar. Five were in Ohio: Antioch, Marietta, Oberlin, Western Reserve, and Ohio Female College. Moving steadily westward one finds Andover alumni at Wabash, Indiana, Illinois and Knox in Illinois, Drury in Missouri, Washburn in Kansas, Colorado among the Rockies, and Pomona in California. In a more northerly latitude are Adrian and Olivet in Michigan, Beloit in Wisconsin, Iowa College in Iowa, and Fargo in North Dakota. Howard University in Washington, D. C, Atlanta in Georgia, Rollins in Florida, Fisk in Tennessee, and state colleges in Alabama and Tennessee, gave wide representation to Andover in the South. For good measure the universities of Wisconsin and Kansas should be added. And overseas were Robert College in Constantinople and the Syrian Protestant College at Beirut [later the American University of Beirut].” (quoting Rowe) North Parish Unitarian Church, North Andover, Mass. Photo Source: Wikipedia. Present structure erected 1834.

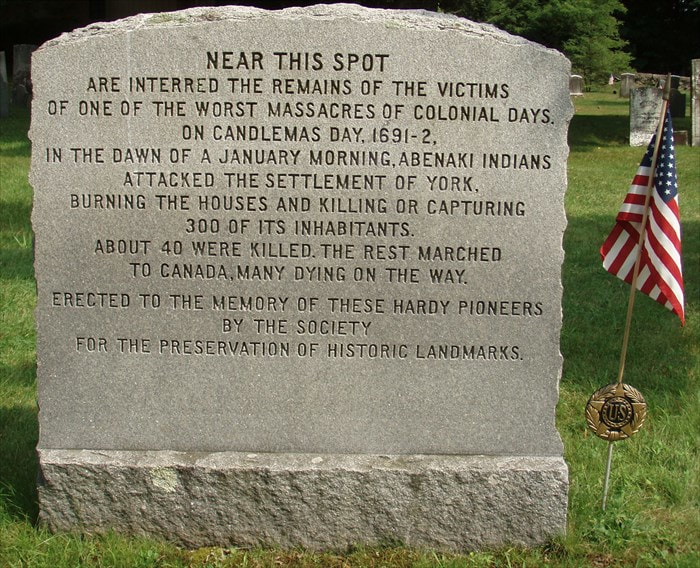

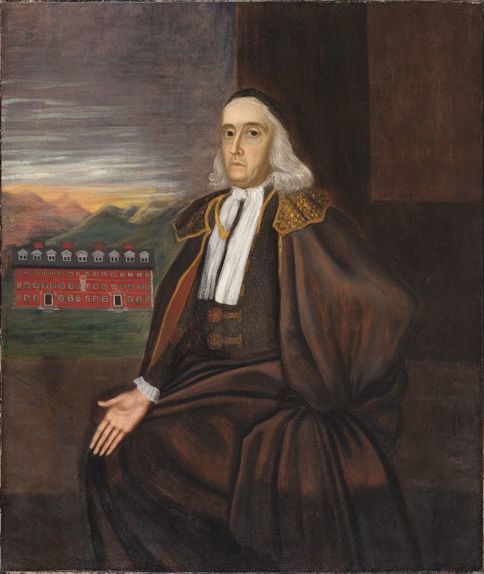

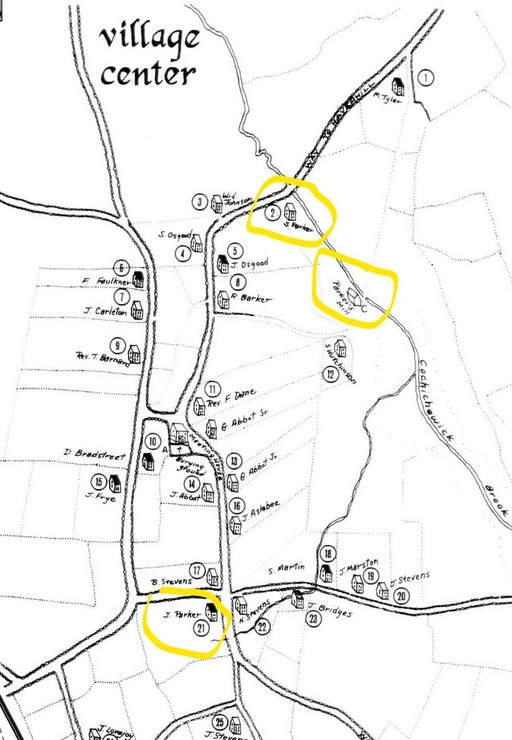

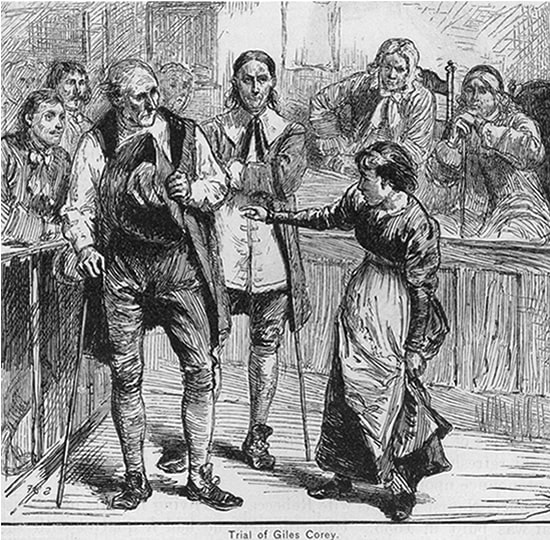

(A long read)Above: Monument to Mary Ayer Parker, Salem, Mass. Source: Find-A-Grave Background By the end of 1678, the first major episode of violence between natives and English colonists was over. Nearly 10% of the English population was killed in this King Philips War, but it was even more destructive for the natives. The eradication of the Narragansett and Wampanoag tribes and the weakening of the other tribes in the settled parts of New England did not mean the threat of Indian invasion disappeared, however. Instead, for the towns along the northwestern frontier of English settlement of North America – places like Haverhill and Andover – the threat actually grew. This is because the remaining natives became proxies in the rivalry between global empires, France and England. Some Indian groups had historically plundered the coastal tribes of New England...for example, the Mohawks from west of the Hudson, and the Ohio Valley-based Iroquois. Members of both tribes became paid mercenaries along the English-French frontier, in what is now Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont. Other tribes were fighting back against the encroaching devastation of their native lands. The Abenaki entered into a formal political alliance with the imperial government of France, seeking an established place in “Arcadia”, which was the colony of New France that extended from the present Canadian maritime provinces all the way down to the Kennebec River. Members of all three tribes became a threat to settlements of the puritan English frontier. Disruption to Lower Merrimack Valley and Northern Essex Region The first imperial proxy war became known as King William’s war, named after the distant English king, William of Orange, a newcomer from Holland who along with his wife Mary had inherited the English throne after the demise of the house of Stuart. He led a coalition of kingdoms against France. The opening volley in our part of the world was an attack directed by the governor of the Province of New England, who in 1688 organized a militia raid on the de facto French military leader of Arcadia, Jean-Vincent d'Abbadie de Saint-Castin, at what is now Castine, Maine, the southern-most point of French settlement. Saint-Castin was married to a Penobscot Indian princess and commanded mainly an army of Indians, aided by Jesuit priest-soldiers. This attack on Saint-Castine triggered war in the region. Abenakis and their French allies retaliated by targeting English settlements far down the Maine coast. They attacked Kennebunk in September of 1688; Salmon Falls (now Berwick) Maine in March 1690 (in which about 90 English villagers were killed or imprisoned for ransom); Wells in June 1691; and York in January 1692 (the so-called Candlemas Massacre in which 300 English villagers were killed or imprisoned for ransom). As a result of these devastating raids, dozens of English families fled southward into the relative safety of the Merrimack Valley and Essex County, past the warring tribulations of Kangamagus, last of the great Pennacook chiefs, near Dover. Below: Memorial to the victims of the Candelmas Massacre, January 24, 1692, York, Maine The refugees mainly swarmed Salem -- divided into Salem Town, now Salem, and Salem Village, now Danvers-- Ipswich, Haverhill and Andover. This influx of refugees strained resources and is thought to have contributed to the social unrest in these areas that caused “witch fever” to take hold. Although the hangings and other executions were centered in Salem Town, the most accusations of witchcraft apparently occurred in Andover, on the frontier twenty miles inland on the banks of the Merrimack. Andover had already suffered one Indian raid in August 1689, when the Peters house was burned and two persons were killed, so paranoia and apprehension likely ran high. Andover in the late Seventeenth Century The frontier region of northern Essex County in the late 1680s and early 1690s barely resembled the wilderness encountered fifty years earlier. Land had been allocated and cleared, and native trails became roads. Tight clusters of wood frame houses surrounded a parish meetinghouse; when the population grew too numerous, residents built houses far away from the meetinghouse. The road to Boston (present-day Route 28) and the road to Salem Town (present day Route 114) were bustling with trade at times, as grain, produce and timber made their way to market; and smoked fish, molasses from the rum trade, and finished goods made from England their way back to the hinterlands. Small boats could make their way up the Merrimack to Haverhill, site of the first falls, called Pentucket by the natives. Grist mills and lumber mills lined the streams, and tanneries and cottage industries provided basic clothing material, with the rest - such as cotton – shipped in through Boston and Newburyport. Despite the prosperity and relative stability of towns like Andover and Haverhill, the threat of Indian raids caused a general tone of apprehension. “The Indians were enemies very much dreaded. They concealed themselves and lay in ambush, and waited long and patiently, for an opportunity to surprise their prey. They never made their attacks openly, nor fought in the open field. The time of assault was often just before dawn of day, when they could strike the blow without resistance, and could cause the greatest panic. The inhabitants did not feel safe in their fields, and were liable to be shot down while at their labor. They frequently carried their firearms with them to their work. They also carried their guns when they assembled for worship on the Sabbath, and were exposed to be way laid in going and returning, and assaulted in the meeting house. They could not rest safely in their beds, without constant watch in time of war. They knew not when the enemy was near; they encamped in the wilderness, and were in the same place only a short time. It was as difficult to hunt them in the forest, as to hunt a wolf, and they were skillful at lying at ambush for their pursuers. Under such circumstances, the early settlers suffered exceedingly, not only from actual assaults, but from alarms and constant apprehension of danger. Their labors were often interrupted, much time was lost, and much expense incurred in securing their families and property. They were exposed, and suffered frequent losses, by destruction of their cattle, horses and barns, and pillage of their fields.” From The History of Andover, Mass. to 1829, by Ariel Abbot (1830). Thus there were grumblings about safety in the face of the obvious threat of Indian attack; however, nothing was done to form new parishes and build new meetinghouses and therefore form defensible new villages until a few decades later. Instead, newer residents lived far afield, in lone houses, on the edge of ancient forests that had yet to be cleared – rocky glacial soil made field clearance a slow and arduous task. Homes were timber frame, built using communal efforts, and covered either with clapboard, shingle or thatch-and-waddle. Some homes were built as “garrison houses” – brick in construction, with small windows that could be shuttered to keep out Indians and resist flame. One such house, the Peaslee Garrison House in East Haverhill, still stands today and was constructed around 1675 by my ninth great grandfather Joseph Peaslee [aka Peasley]. Above: Peasley Garrison House, East Haverhill, Built 1675 (now a private residence). Photo by the author. Similar garrison houses were erected on the periphery of Andover. Religious changes were evident too, causing further strain. The first two generations of New England puritans had been staunch believers, ready to sign up to covenants with their local puritan Meetinghouse vowing pure and virtuous life. Calling the churches “meetinghouses” signified the complete merger of religious life with civic life; all local governance took place within its walls. The right to vote in the local community was tied to membership in the church, which was limited to the elect who had undergone conversion by faith. But by the third generation, in the 1660s, there was a crisis. Were the grandchildren of the puritans who made the perilous journey to the new world presumed true believers? Or did they need to undergo their own personal “conversion”? A compromise was reached – they could sign up for a “half-way covenant”, in which, despite lacking a conversion experience, they could attend worship, but not receive rights to vote. This was the beginning of separation of local church and local government. By the 1690s, we were on the fourth generation, and church membership was plummeting… along with control of mores in the community, said the ministers. Yes, heresies in Boston had been dealt with, such as the expulsion of the Baptist Roger Williams to Providence plantation in 1636, the expulsion of Anne Hutchinson to New York in 1642 and the hanging of Quakers in Boston in the 1660s. However, apathy and alienation were harder to combat than zealous heresy. This was the context of the Salem witch trials. In addition to being the result of social strain wrought by King William’s War, the expansion of witch hysteria arguably represented an attempt by puritan leaders to use the situation to impose moral judgment. Sentences in the witch trials were handed down by William Stoughton, former puritan minister turned politician, who allowed most of the cases to be heard on the basis of spectral evidence: claims by witnesses of supernatural sensations. The court, after handing down its first execution in June 1692, adjourned to obtain advice of leading puritan ministers, who rallied behind the court’s purpose. The primary point of advice of the minsters was for the court to bring utmost help to those suffering molestations from the invisible world, by “speedy and vigorous prosecution of such as have rendered themselves obnoxious.” Below: William Stoughton, the Hanging Judge of the Salem Witch Trials, sitting in front of Harvard College, the seat of learning for the puritan ministry (Source: Wikipedia) Witches in the family John Ayer, the paterfamilias of all the Ayers in Haverhill and surrounding towns and my tenth great grandfather, passed from this mortal plane in 1657, in Haverhill. He left at least seven surviving children. His wife Hannah lived until 1688, dying at a ripe old age. By some accounts she was more than a hundred when she passed. John Ayer’s inventory upon death included “fower [four] cows, two steers, and a calf; twenty swine and fower pigs; fower oxen; one plough, two pair plough irons, one harrow, one yolke and chayne, and a rope cart; two howes, two axes, two shovels, one spade, two wedges, two betell rings, two sickels and a reap hook hangers in the chimneys, tongs and pot hooks; two pots, three kettles, one skillet, and frying pan in pewter; three flocks, beds, and bed clothes; twelve yards of cotton cloth, cotton wool, hemp and flax; two wheels, three chests, and a cupboard; ‘wooden stuff belonging to the house’; two muskets and ‘all that belong to them’; some books; some meat [presumably cured] about ‘fo[t]rie bushells of corne’; his wearing apparill; about six or seven acres of grain in and upon the ground; the dwelling house and barne and land broken and unbroken with all appurtenances forks, rakes, and other small implements about the house and barne.” Thus, he prospered in the new world. Their son Robert, my ninth great grandfather, was designated a freeman in 1666, made a selectman in 1685, and was known as sergeant of the local militia after 1692. He was even more prosperous than his father, whereas the refugees and other newcomers had virtually no possessions, eking out existences as boarders and field workers. Witchcraft came to the Ayer family when Robert’s sister, Mary Ayer Parker, of Andover, was accused of witchcraft in early September 1692, six months into the witch craze. She was hanged by the end of that month, proclaiming her innocence until her death. Mary had been married to Nathan Parker, a former indentured servant who had settled in Newbury with his brother Joseph sometime in the 1630s. By 1648, Nathan had bought his freedom and was living in Andover, as one of its first settlers. His first wife died, and within a few months he married Mary Ayer. The original size of Nathan Parker’s house lot was four acres but his landholdings improved significantly over the years to 213.5 acres. His brother Joseph, a founding member of the meetinghouse in Andover parish, possessed even more land than his brother, increasing his wealth as a tanner. By 1660, there were forty household lots in Andover (clustered around what is now North Andover common, the original village of Andover), and no more were created. Subsequent landholders built their homes far afield, near their farms. By 1650, Nathan began serving as a constable in Andover. Nathan and Mary had their first child, John, in 1653. Mary bore four more sons: James in 1655, Robert in 1665, Joseph in 1669 and Peter in 1676. She and Nathan also had four daughters: Mary, born in 1660 (or 1657), Hannah in 1659, Elizabeth in 1663, and Sara in 1670. Her son James died on June 29, 1677, age twenty-two. He was killed in a battle with Indians at Black Point, in what is now Scarborough, Maine, in one of the last skirmishes of King Philips War, along with his cousin John Parker (son of his father’s brother Joseph Parker), who had fought in the Great Swamp campaign in Rhode Island a few years previous. Nathan Parker, husband of Mary Ayer Parker, died in June 1685. He left an estate valued at 463 pounds – more than double the estate of his father-in-law John Ayer – and a third of it went to Mary his wife. It is not known what her lifestyle was like after 1685; however, she was likely living alone as all her children were grown and all the girls were married by this time and living in their own homes. Below: detail of map of Andover [now North Andover common] in 1692 prepared by the North Andover Historical Society. It's not clear which residence would have been Nathan Parker's. The accusation of witchcraft against Mary Parker She was accused by fourteen-year-old William Barker Jr. in his confession on September 1, 1692. Young William’s father, William Sr., and his thirteen-year-old cousin Mary Barker, daughter of the deacon of the Andover meetinghouse, had already been imprisoned for witchcraft three days earlier. The accused William Jr. stated that he had so recently converted to witchcraft that he “had only been in the snare of the Devil for six days.” He testified that "Goody Parker went with him last Night to Afflict Martha Sprague." Goody was an abbreviation of goodwife, a title used for most married women in puritan Massachusetts. Young William elaborated that Goody Parker "rode upon a pole & was baptized [by Satan] at Five Mile pond." [Now called Haggetts Pond] The examination of Mary Ayer Parker occurred the next day. At the examination, afflicted girls and young women from both Salem and Andover fell into fits when her name was spoken. These witnesses included Mary Warren (a twenty-year-old servant), Sarah Churchill (a refugee from Saco, Maine), Hannah Post (a twenty-six year old whose father Richard had been killed by Indians), Sara Bridges (Hannah Post’s seventeen year old stepsister), and Mercy Wardwell (age nineteen, already under arrest for witchcraft, daughter of wealthy Samuel Wardwell of Andover, who was eventually hanged for witchcraft the same day as Mary Parker). The records state that when Mary came before the justices, these girls and young women were cured of their fits by her touch, which was the satisfactory result of the commonly used "touch test," signifying a witch's guilt. Below: A witness performing the touch test on Giles Corey, accused of witchcraft Mary Ayer Parker was tried in Salem. During her examination she was asked, "How long have ye been in the snare of the devil?"

She responded, "I know nothing of it.“ Her defense was mistaken identity: other Mary Parkers lived in Andover – by whom she would have meant either her brother-in-law Joseph Parker’s wife Mary, nee Stevens, or their daughter. It was not clear why she would have tried to throw her relatives ‘under the bus’ (to use an anachronistic phrase). Perhaps there were still hard feelings over the death of her eldest son James after he followed their son John, his first cousin, into war against the Indians. In any case, the court did not buy her defense. Like most accused in the witch trials who protested their innocence rather than confessing being in league with the devil, she was found guilty and hanged. Conclusion Some people think the witch trials were purely the result of the belief systems of the Massachusetts puritans. However, they came into existence at a time of great social stress, as refugees fleeing horrifying Indian raids along the Maine frontier upset the social order of towns like Andover and Salem where they sought shelter. The belief system of the Puritan ministers became a weapon that could be used in a form of class warfare, in which the marginalized could bring down their superiors, especially ones haughty enough not to admit they were in fact witches. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed