|

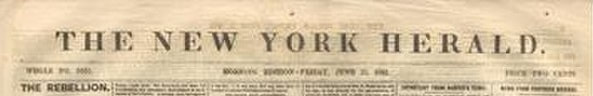

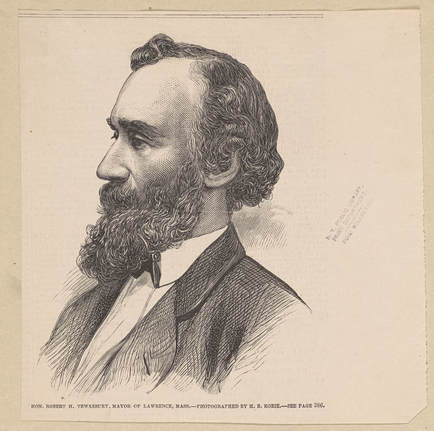

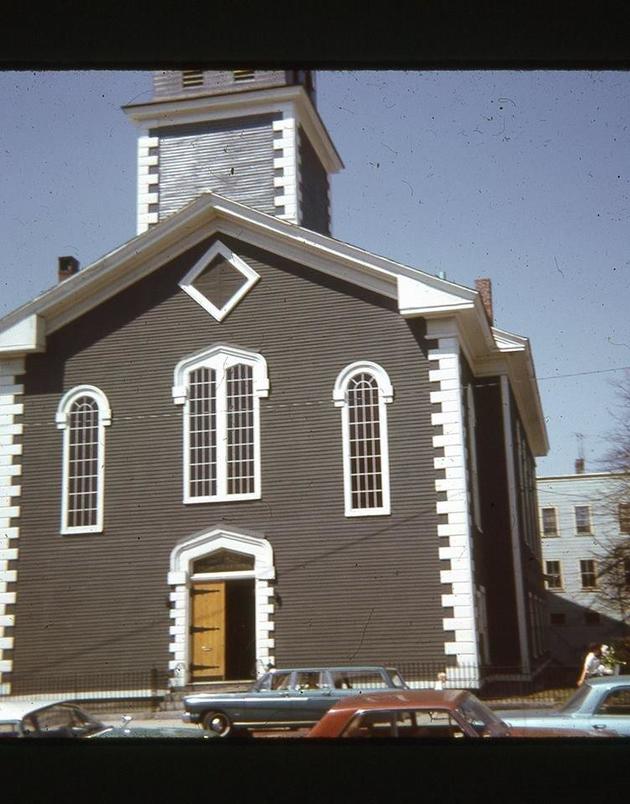

If you’re over forty, you probably remember bumper stickers like this all over Massachusetts: Among persons of Irish descent, support for the Irish Republican Army (IRA) was widespread, even if it was superficial. Somehow it was okay to like Princess Diana and Irish republicans… The IRA story was easy to understand. The British army was an occupying force. IRA men were freedom fighters, naturally fighting for a unified Ireland. British empire, bad. Freedom fighter, good. It’s all very romantic. Almost nobody from the area knows the story of the “other side”, the so-called Ulster Orangemen, who also made the region of Ulster their home. They were fighting for minority rights just as much as the IRA. Below: Logo of the Ulster Defence Association, paramilitary group The history of the Orangemen in a nutshell Ireland was ruled by the English crown starting in the 1500s. In the early 1600s, Scotland was technically still a separate kingdom. The English king had a problem. What to do with all those pesky Scots who lived on his side of the English-Scottish border? They kept trying to rise up against him. Solution: deport them to Ireland. These “Scots-Irish” (Americans like to say Scotch-Irish) were given land and rights in the province of Ulster, which was called a Plantation. They were supposed to raise sheep and pursue other productive ventures. Some of them soon left Ulster and settled the hillbilly regions of the United States. That’s another story. The ones who remained in Ulster had a tenuous relationship with the English powers. They refused to kowtow to the Anglicans who ran everything. Instead, they followed a very Calvinistic form of Presbyterianism. Although they had more rights and wealth than the Catholic population, they were an often-second-class minority within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Below: Political Cartoon from 1913 Regarding Ireland "Home Rule" When Ireland began to break away from Great Britain, the Ulster Scots leveraged their close-knit status as a political force. They won the separation of most but not all of the Ulster province from independent Ireland. The section in which they were a majority remained with Great Britain. The Ulster Scots saw themselves as a beleaguered minority of Ireland proudly clinging to their traditions. The British crown was now their protector, hence their extreme loyalism. The Orangemen One of the big traditions among Ulstermen is a commemoration of the Battle of the Boyne (July 12, 1690). In this battle, Protestant William of Orange, who rule as co-regent with his wife Mary II (hence the reign of William & Mary), defeated the deposed King James II, thus thwarting James’ failed bid to restore Catholicism to Great Britain. To commemorate this victory, Orangemen hold marches. During the “Troubles” of Northern Ireland, from 1969-1998, often these marches were designed to provoke their Catholic rivals, just as republican (meaning pro-Republic of Ireland) countermarches were designed to provoke Ulster communities. Technically, the Orangemen are a fraternal organization, comprised mainly but not exclusively of Ulster Scots (some are descended from English settlers of Ulster). It was technically founded as a brotherhood for all Protestants, in 1795 in County Armagh in Ulster. Below: Typical procession of Orangemen in Northern Ireland, July 12, 2016. PHOTOGRAPH BY Michelle McCarron. What does any of this have to do with the Merrimack Valley?? On July 12, 1875, the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne, a group of self-styled Orangemen held a picnic on the banks of the Merrimack River in Methuen. When they returned to Lawrence by way of steamer to Water Street, they were met a mob of 200 Irish Catholics. A riot erupted, and police fired at the mob. Here is the coverage from the New York Daily Herald: “Lawrence, Mass. – A serious riot occurred in this city to-night, resulting from an outbreak made by a mob upon the members of a lodge of Orangemen returning from celebrating the ‘Battle of the Boyne’ at a picnic at Laurel Grove, four miles up the Merrimac River. Orangemen from Lowell, Woburn and other towns participated at the picnic, which passed off quietly, and no trouble was anticipated when they dispersed for their homes, though some threats had been made in the morning and some of the men carried firearms in consequence. MOBBING THE LADIES About a dozen Orangemen, with ladies and children, disembarked at eight P.M., at the steamer landing on Water street, and started to walk up town. A crowd of several hundred Irish were at the landing and followed them, shouting and jeering. When they arrived in front of the Pacific Mills, the crowd commenced throwing stones, one of the ladies being struck three times and badly hurt. All the party were more or less injured by missiles thrown at them during their half mile walk to the police station, whither they went for protection. Four of the men had on regalia, which particularly incensed the mob. One of the men was severely hurt about the head and had his sash torn from him THE MAYOR JEERED AT On their arrival at the police station word was sent to the Mayor [ed: Robert H. Tewksbury], who soon arrived at the scene and undertook to disperse the mob of men and boys, but without avail; the cries and jeers of the mob drowned his voice. The Mayor, with a squad of police [editorial note: who were probably mostly Irish Catholic!], then started to take the party through the crowd to their homes. SHOWERS OF STONES Essex Street, through which they had to pass, was at this time filled for half a mile with the mob. Showers of stones, bricks and other missiles was [sic] hurled at the party as soon as it appeared upon the street. With the exception of the Mayor every one of the party was hurt. Policeman Gummel was knocked down and badly hurt. James Sprinlow, who was endeavoring to protect his brother’s wife, was knocked down, received a terrible wound in the head from a brick. At the corner of Union and Spring streets the mob made a furious onslaught of the party, when nearly all the police and Orangemen were knocked down. The latter then, in self-defense, drew their revolvers and began firing on them on the mob, who were shouting ‘Kill the damned Orangemen.” THE WOUNDED The firing quickly dispersed the mob, who scattered in all directions. It is impossible to learn the accurate result of the shooting. So far as known no one was killed. Two men, one woman and a boy twelve years old, were wounded; none seriously. Of the Orangemen twelve were wounded by stones and bricks, some of them quite seriously, and four policemen were more or less hurt. COURAGE OF THE MAYOR The riot lasted two hours and a half, and extended over a route of a mile through the most thickly portion of the city. It is the most serious affair of the kind that has occurred since 1852 [sic? Is this right? I thought the anti-Irish riot was in 1854], and is condemned on every hand as most unprovoked. The courage of the Mayor undoubtedly saved many lives.” Below: Robert Haskell Tewksbury (1833-1910), Mayor of Lawrence in 1875 Mary O’Keefe, whom I have written about, condemned the riot. She specifically cited the efforts by Irish Catholic clergy to distance themselves from the events. “And now we come to an event which we are doubtful about mentioning in a sketch of Catholicity in Lawrence for testing as we do, that Catholicity had no share in it. We refer to the ‘Orange riot’ which took place on the 12th of July, 1875, the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne, and was, by an accident, very largely advertised all over the country, and, of course, ridiculously exaggerated. However, lest we should be understood as acknowledging, by our silence, the truth of these reports, we here insert a card signed by the Catholic clergy of Lawrence, and published, at the time, in all the local papers. It expresses not only their sentiments, but those of all others in the city deserving the name of Catholics. “We, the undersigned, Roman Catholic clergymen of Lawrence, desire to publicly make known our condemnation of the riotous proceedings of last Monday evening. We do not consider as Catholics, in the proper meaning of the term, those who participated in the disturbance of the public peace, and who, by their shameful conduct, sullied the fair fame of our city. We teach our people good will towards all men, and we strive, by precept and example, to impress upon them the importance of faithfully observing the laws. We trust that the few ruflians who, under the name of Catholicism versus Orangeism, have created such bad feeling and given rise to so much trouble, may be made to feel the enormity of their crime. – SIGNED W. H. Fitzpatrick, Pastor of the Immaculate Conception Church; J. H. Mulcahy, Asst. Pastor of the Immaculate Conception Church; Jno. P. Gilmore, D. D. Regan, J. A. Marsden, O. S. A., Pastors of St. Mary’s Analysis and Questions What I would like to know: were these marchers really Orangemen, meaning they were really of Ulster descent? I have never heard of any Scots-Irish living in Greater Lawrence. I asked the Lawrence History Center, who have a redoubtable collection of materials related to dozens of different immigrant groups to the area. They have nothing on Scots-Irish, Ulstermen, Orangemen or anything similar. (There was however a large Scot-Irish settlement in Londonderry, New Hampshire - however, this town is probably too far away to have been the source of these marching "Orangemen".) I can’t help but think the march was of anti-Catholic types, of which there were still many (soon I hope to write about the Catholic school controversy of 1888 of Haverhill). But more research is needed. If anyone’s ancestor was a member of the Grey Presbyterian church in Lawrence, it would be great if you could contact me about the origins of your ancestors. Below: First Presbyterian Church (The Grey Church), 315 Haverhill Street(?), Lawrence, Mass.

0 Comments

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed