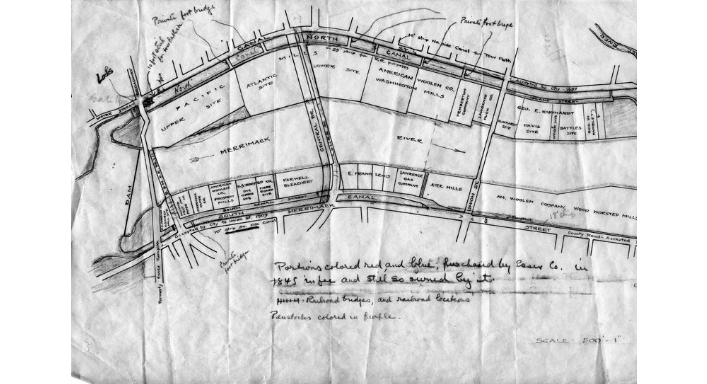

Above: Katherine O'Keefe O’Mahoney, born Ireland 1855, died Lawrence, Mass. 1918 (Source: Lawrence, Massachusetts by Ken Skulski, 1995) The Backstory Before there was Lawrence, there was ye olde New England: clapboard farmhouses, village greens, slow-moving farmers who mended their stone walls and carted their produce to market. This is how things were in 1845, the year Lawrence was founded as a town. Things in 1845 really weren’t all that different from 1645, two hundred years earlier, when the area was first settled by English Puritans in the towns of Andover and Haverhill. The ancient towns were later carved into the towns that we know today – Methuen, Salem N.H. (both formerly part of Haverhill), North Andover (the original part of Andover)…and Lawrence. Sure, the railroad had been introduced a decade earlier, and the Puritans had mellowed somewhat. People were no longer executed for witchcraft or whipped for heresy. But the culture was basically the same as it had been for generations. The original Puritan settlers had come forth and multiplied, cleared the land, built meetinghouses. Some of them went off to sea, chasing whale oil or Far-East silks and spices; or enterprisingly built waterwheels to grind their neighbors’ grain. Some of the local militia boys had gone off to the Battle of Bunker Hill and other early encounters of the Revolution. Basically, however, people farmed, traded, read their King James Bibles, attended meetinghouse, lived and died. Things were homogeneous and consistent, generation after generation. Below: Typical New England farm of the early 19th Century, similar to Bodwell's Farm in what became Lawrence (Source: New England Historical Society) Then, in the second half of the 1840s, two things happened: (1) industrialization and (2) a refugee crisis. Here Come the Factories The fast-moving tributaries of the Merrimack River had always powered waterwheels – little mills that were used to grind grain, saw logs into boards, or run a few looms to supplement the homespun cloth. However, in the 1840s, the mills being planned were different: they would now be on a grand scale. The immense new wealth of the spice trade and whaling was chasing new investments, and could finance endeavors on a previously unimaginable scale. The industrial revolution was underway in Britain and provided the technology. The planned textile city of Lowell was the first example, as we all know, but bigger and bigger factories could be planned. So a group of rich Boston merchant pooled their capital to form the Essex Company. In 1845 this company started to build Lawrence in a backcountry corner of Essex County, smack in the middle of farmers’ fields that had been cleared two centuries earlier. Their project – to build the largest dam in the world across the Merrimack and force its waters down two long canals to power dozens of enormous mills – required a lot of labor, the cheaper the better. Below: Plan for Lawrence showing new dam, canals and plots for water-powered textile mills, 1845 (Source Digital Public Library of America) Here Come the Irish Refugees And who should conveniently show up but a bunch of Irish refugees who could be put to work for pennies a day? These rag-clothed, impoverished, filthy bands of people were escaping the biggest humanitarian crisis of their time. The Irish Potato famine was so severe it killed one third of the people and forced another third to flee. The Famine Irish had arrived on dangerous, unseaworthy “coffin ships” operated by unscrupulous people-runners looking to exploit the desperation of the refugees. A risky voyage across the water was nevertheless preferable to staying in Ireland. Below: A So-Called Coffin Ship Leaving Queenstown (Now Cobh) Ireland, 1848 The Irish migrants crowded the port of Boston, then made their way inland, likely on foot, looking for work. The stream of refugees began in 1847 and did not abate until the mid-1850s. At Lawrence, they formed their refugee camp – the shantytown on the southern bank of the Merrimack – and the men started working on the dam. One of these laborers was my great great grandfather, Jeremiah Driscoll, arrived from Ireland in 1851 at age 29. He worked as a laborer for the Essex Company. His home address in the Lawrence town directory, once the town was big enough to have a directory, was “Shantytown, South Side.” Other Irish built a shantytown/refugee camp on the plains above Haverhill Street, near the Spicket River. A report from 1870 stated that some shanties had to be cleared for construction of the Lawrence reservoir. One of them was 120 feet long, and made of rough boards. It housed 80 people, mostly single men but also a family who built the place and charged the boarders a half penny a day to shelter there. Below: Derogatory Cartoon Depicting Shanty Irish Irish Pride in Early Lawrence Fast forward thirty-five years or so to 1882. Lawrence has grown from a couple hundred residents to 38,000…and around half of them are Irish. Although the town is seven square miles, most folks are concentrated in walking distance of the mills lining the river, spanned now by three bridges. There are by this time over a dozen large textile mills with more being built. The Irish, though largely still poor, have survived massive prejudice and exploitation within a largely hostile Yankee society. What do they do to show their pride? Do they march in a St. Patrick’s Day parade? Hardly – the first proper St. Patrick’s Day parade in Lawrence wasn’t until the 1900s. Go to a Riverdance concert? Listen to the Dropkick Murphy’s? No: they celebrated their Catholic faith by building magnificent churches and then organizing their lives around them. Below: Interior, St. Mary's Church, erected Lawrence, Mass. 1871

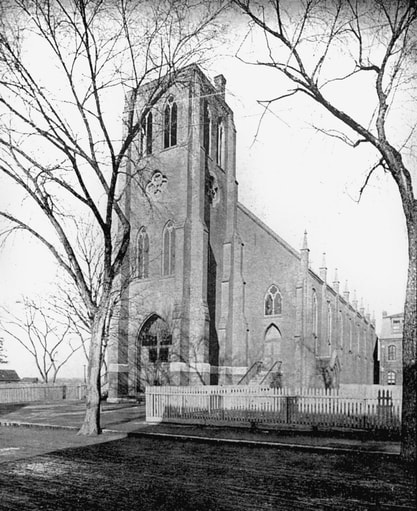

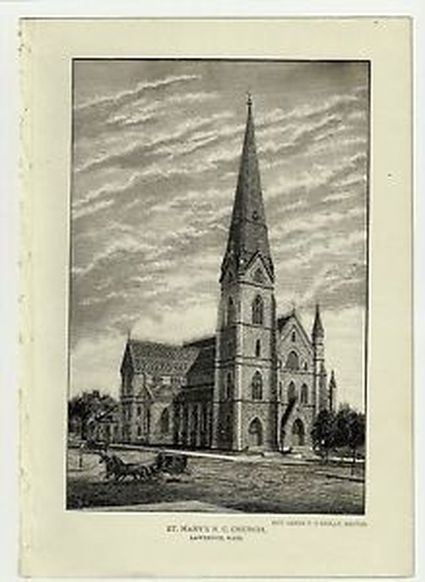

As one observer wrote, the Irish were known to spend their money on beautifying their houses of God before they beautified their own homes. Indeed, in 1882, three grand churches had been constructed of granite and brick in Lawrence – Immaculate Conception on Chestnut Street, St. Mary’s on Haverhill Street, and St. Lawrence O’Toole at the corner of Essex and Union Streets (it was renamed Holy Rosary in 1904 when the new St. Laurence O'Toole was built on East Haverhill Street). Yet at the same time, many Irish in Lawrence still lived in shanties. The last shanty was not torn down until 1894. Above: Immaculate Conception Church, Chestnut Street, Lawrence (Source: Queen City Blog). Lawrence's first permanent Catholic church, torn down 1991.The sense of Irish pride in their Church and its institutions – its grand churches, its rigorous schools, its charities like orphanages and hospitals – is captured in an 1882 book, “Catholicity in Lawrence” by Katherine O’Keefe O’Mahoney. According to Ken Skulski’s history of Lawrence, O'Keefe was “an author, lecturer and educator”. Irish-born, she graduated from Lawrence High School in 1873 (a rarity for girls, especially an immigrant girl), and then she started working there as a teacher. “Robert Frost considered her one of his favorite teachers. She was also among the first Irish-American women to lecture in New England. Her books include A Sketch of Catholicity in Lawrence and Vicinity (1882) and Famous Irishwomen (1907).” She also published a newspaper for Irish-American Catholics in Lawrence and conducted Irish classes there. She died at her Tower Hill home in 1918 at age sixty three. (Source: Ken Skulski’s Lawrence, Massachusetts.) For the about the first thirty year's of Lawrence's existence (until French Canadians started to arrive), pretty much the only Catholics in Lawrence were Irish. Reading O'Keefe's proud descriptions of St. Mary’s Church, you can get a sense of the importance of a magnificent church like this to the community:

Below: St. Mary's Church, Lawrence, Mass. erected 1871 For her, the priests are towering figures, and funerals of priests are the equivalent of a funeral for a head of state. The following is from her description of the 1875 funeral of Father Louis Edge, O.S.A., who built St. Mary’s along with the Augustinian Order. She claims that 10,000 people viewed his body lying in state in his coffin in front of the altar. Note the participation of the numerous Irish social and religious organizations: “Early on Monday morning, crowds began to assemble in the vicinity of the church, awaiting the opening of the doors. The Ancient Order of Hibernians, numbering nearly 150 men, were the first to enter, and to them was assigned the East wing; after them came the Ladies’ Sodality of St. Mary’s Church, with medals and white veils. They numbered over seven hundred, and presented a beautiful appearance. The Irish Benevolent Society, headed by the Lawrence Brass Band, were the next to enter the church. They numbered nearly two hundred, and bore a silken mourning banner; they were seated in the Gospel aisle. Next came the Ladies’ Sodality of the Church of the Immaculate Conception, in white veils, similar to St. Mary’s Sodality; they had been assigned to them the West wing. After them came the Men’s Sodality of St. Mary’s Church, wearing white sashes and white crosses; they were placed in the Epistle aisle. And then came the Catholic Friends’ Society, and the Conference of St. Vincent de Paul. The church was tastefully draped in mourning, the black festoons in the galleries were relieved with white rosettes, and the mourning on the altar with small white crosses. Over the altar was a large cross, formed of blazing gas-jets; and there was a star of gas-jets [!] in front of the organ. When the clergy, forty-six in number, entered the sanctuary to chant the Solemn Office, the scene was truly grand and impressive.” She then goes to name each of the forty six priests in attendance, treating each one as a celebrity. “The architect of this magnificent structure was [Irish-born] P. C. Keely of Brooklyn, N. Y.,” she continues. He was in fact one of the preeminent architects of Catholic churches in the Northeast in the latter half of the nineteenth century. “The stone work was under the supervision of James Trainor of Boston; the wood work was superintended by James Bulger of Burlington, Vt; and the painting, as we have recently stated, was by Schumacher of Portland, Me. Its cost was over $200,000.” Given that this amount was largely raised by small donations from the commuity, it is quite an amazing sum considering that a laborer made a couple dollars a week. Later, she describes the fundraising campaign to pay for the bells of the church (weighing a total of over 10,000 lbs). The list of donors reads like a directory of Irish residents of Lawrence: John Kiley, Sr., Patrick Moran, John Brennan, Patrick Connors, Joseph Morrissey, James Kilbride, Anne O’Donnell, Mary Anne Quinn, Mary Connolly, Mary Burke, Bridget Bradley, Catherine Cushing, Thomas Regan, Mary Dowd, Mary O’Brien, Mary McCarthy, Rose Walsh, Mary Burns, Sarah McGuohan, Maria O’Sullivan, Annie M. Rafferty, Kate Reilly, Ann Mahon, Mary McGuinness, Rosanna Mulligan, Ellen McCavitt, Hannah Moriarty, Mary J. Sweeney, Ellen Ryan… The list extends for a couple hundred more names, three quarters of them obviously Irish in origin. Far more than half of them are women. Katherine O'Keefe O'Mahoney dedicated her life to promoting Irish pride. I have newspaper clippings of a lecture tour she did in 1911, about Ireland featuring numerous illustrations. She is billed as "a little woman with an enormous voice." Irish Legacy In the Catholic Church By focusing on their religion as a defining institution of being Irish, the Irish came to dominate the Catholic Church in America. “In 1880, the percentages of the clergy who were Irish American was 69 percent in the Archdiocese of Boston…Moreover, in 1886 thirty-five (51%) of the sixty-eight Catholic bishops in America were Irish born or of Irish descent. In 1920, it was still the case that two-thirds of Catholic bishops were Irish American, and in New England, that proportion was three-fourths.” (Source: American Catholics in the Protestant Imagination: Rethinking the Academic Study of Religion, by Michael P. Carroll, 2010) Later, when other Catholic immigrant groups followed - first the French Canadians, then the Poles, Italians, Portuguese, Lithuanians and (a few) Catholic Germans -- they found waiting for them a church that could provide something of a welcome, whereas the Irish basically had to create the Church in New England. Epilogue Since the early 1990s, many of the grand Catholic churches of the original Catholic communities of New England have been closed and often torn down. In Lawrence, this includes the aforementioned Immaculate Conception and St. Lawrence O'Toole, as well as half a dozen other churches. The same pattern was repeated in other urban centers: Lowell, Haverhill, Fall River, Worcester, Boston. I hope this and other blog posts will remind people that these abandoned churches were not just religious institutions, but were part of the physical culture of the immigrant groups who built them. Below: Today's St. Mary's church (Santa Maria de la Asunción)(source: church website)

13 Comments

Daniel Saunders..."founder" of Lawrence, Mass., rube [?] and fifth great uncle by marriage [!]12/17/2017 Above: My home until age 2 1/2, Saunders Street, Lawrence, Mass., circa 1973

Today while researching something else --- the early industrial history of Andover, Mass., which later split into two towns in 1855 --- I came across a description of Daniel Saunders, effectively the founder of Lawrence in 1847. He's considered the founder on account of his owning most of the land on which Lawrence was built, in the sandy backcountry of Andover's West Parish known to locals as "Moose Country". For the first time I noticed that he married a daughter of Caleb Abbot, of Andover. I have a 5th great grandfather named Caleb Abbot (1751-1837), who was at Bunker Hill as a militiaman. Caleb Abbot and wife Lucy Lovejoy, also of Andover (1757-1802) had at least fourteen children, one of whom was my 4th great grandmother Elizabeth Abbot (born Andover 1791, died Lawrence 1880), who married a French Huguenot's grandson, Samuel Stevens Valpey (1795-1876). Valpey's claim to fame was ownership of the first commercial butcher in Andover, at 2-4 Main Street. This Valpey's mother was also named Elizabeth Abbot, of Andover (1766-1833) and so presumably Sam Valpey married a cousin of his. As an aside, in my genealogical research I have come across a lot of tangled knots of consanguinity when researching Andover ancestors, all seemingly named Abbot, Lovejoy, Osgood, Stevens, etc. But that's a story for another time. A few searches in Ancestry.com and LO AND BEHOLD! Said Elizabeth-the-younger-Abbot had a sister, Phebe Foxcroft Abbot --- Foxcroft being another old Andover name--- born Andover in 1797 and died in Lawrence in 1888. She was married to this very same Daniel Saunders on June 21, 1821 in Andover...making the founder of Lawrence my fifth great uncle by marriage. As a result, Daniel and Phebe's children, including Daniel Jr. (elected mayor of Lawrence in 1860) and Caleb (elected mayor of Lawrence in 1877) are my first cousins five times removed. A lot of things in Lawrence are named Saunders... including Saunders Street, where I lived until I was two and a half years old. Go figure. The biography of Daniel Saunders, Sr. that I came across today, in "Historical Sketches of Andover" (1880) by Sarah Loring Bailey, borders on hagiography in its positive review. It is worth quoting in its entirety if only for its details. However, as I discuss below, this glowing account might not have been deserved, as Saunders did not by any means become a rich man. Instead, the wealth of Lawrence went to his capitalist backers, the "Boston Associates," who likely got his lands for a pittance compared to the returns they made. A Glowing Account of Daniel Saunders, Sr., founder of Lawrence, Mass. "Daniel Saunders learned the business of cloth-dressing and wool-carding in his native town, Salem, N.H. He came to Andover in 1817 to seek employment, and, after working on a farm, entered the mill of Messrs. Abel and Paschal Abbot, in Andover, where he ultimately obtained an interest in the business, taking a lease of and managing the mill. Being solicited by his former employers to return to his native town and start a woollen mill there, he did so, and remained for a time, but, about 1825, removed to Andover, and settled in the North Parish [now North Andover], for a time leasing the stone mill erected by Dr. Kittredge, and afterward building a mill on a small stream which flows into the Cochichawick. Here he carried on the business of cloth-dressing and wool-carding for some years. In 1839 or 1840 he purchased a mill in Concord, N, H., and carried on manufacturing there, but retained his home at North Andover. About 1842 he gave up the woolen mill at North Andover, sold his house to Mr. Sutton, and removed to what is now South Lawrence, Andover West Parish, south of the Merrimack River, near the old "Shawsheen House." The tract of country in this vicinity was flat and sandy, covered principally with a growth of pine trees. It went by the name of Moose Country. At the point near Mr. Saunders' house, which was a more improved and attractive locality, were two taverns, the Shawsheen House and the Essex House. These were relics of the palmy days of the old stage routes and turnpikes and the Andover tollbridge which, erected in 1793 at a great cost [site of the present-day O'Leary Bridge in Lawrence], was the wonder of the country people and the sorrow of the stockholders for many years. This "Moose Country" was the ancient "Shawshin Fields," where, during the Indian wars, blockhouses were built, to protect the Andover farmers in their ploughing and planting and harvesting. The neighborhood of the taverns was, during the provincial period and the Revolution, and even down to the present century, a considerable business center. The taverns, long owned by the Poor family, had store of legend and tradition connected with them. The bridge was also freighted with memories and anecdotes, which old settlers handed down to the younger generation. Even in Mr. Saunders' day, the glory had not all passed away. Here was the grand gathering to welcome General Lafayette, when in 1825 he made his tour from Boston to Concord, N.H .; and here glittered resplendent the cavalcade of Andover troops which escorted the hero on his journey. But with the decline of the turnpike [present day Route 28] and the stage lines, and the advent of the railway, the prosperity of Moose Country waned; the taverns became silent, the bridge comparatively deserted, and the river Merrimack flowed amid scenes almost as solitary as when the Indian paddled his canoe, and was the sole tenant of the forests. But to the seemingly practical man of business, who had taken up his abode in these solitudes, they were suggestive of schemes and plans of activities which to the ordinary observer seemed as visionary as any ever cherished by the writers of romance. The former glory of Moose Country was nothing in comparison with the brighter days which he foresaw. From a careful study of the river, he came to the belief, not till then entertained, that there was a fall in its course below the city of Lowell sufficient to furnish great waterpower. He became so confident of this, and of the ultimate improvement of this water-power, that he proceeded to buy lands along the river which secured to him the control of flowage. This he did without communicating his plans to any of the citizens. Having made all things ready, he secured the cooperation of capitalists, to whom he unfolded his project. The Merrimack Water Power Association was formed, of which Mr. Saunders and his son, Mr. Daniel Saunders, Jr., then a law student in Lowell, became members, Mr. Samuel Lawrence, of Lowell, being Chairman, and Mr. John Nesmith, Treasurer. Mr. Nathaniel Stevens, and other citizens of Andover, also joined the association. When the scheme began to be talked of, it created a great sensation among the farmers who owned most of the land along the river. Their ancestral acres assumed a sudden importance in their eyes. They had to decide whether they would sell for double the money which ever had been offered for the lands, or whether they would hold the property in hope of greater gain. The company could not at first decide at what point to construct the dam, whether at its present site, Bodwell's Falls, or farther up the river, near Peters's Falls. They, therefore, bonded the land along the river. This, however, it was difficult in some cases to do, and some parties of Andover refused entirely to sell, so that the new city was built up at first mainly on the Methuen or north side of the river [Methuen being split off from Haverhill in 1725]. In March, 1845, the Legislature granted to Samuel Lawrence, John Nesmith, Daniel Saunders, and Edward Bartlett, their associates and successors, the charter of the Essex Company, authorizing, among other things, the construction of a dam across Merrimack River either at Bodwell's Falls or Deer Jump Falls, or at some point between the two falls. The dam was begun in 1845, and was three years in building. The completion of it made a fall almost like a second Niagara in breadth and volume of water. The unbroken sheet of water was 900 feet wide, the masonry 1,629’ in length, and rising in some parts over forty feet in height. The thunder of the cataract, when the dam was first built, could be heard for two or three miles. The old Andover farmers "could not sleep o' nights," as they said, for thinking what might happen in the spring freshets, and the jarring of the ground was so great near the river bank as to rattle doors and shake down dishes in the cupboards, and seriously disturb the equanimity of orderly housewives. It would be a long task to recount all the predictions, fulfilled and unfulfilled, made by the wiseacres, from the day when " Saunders's folly " was their theme, to the day when, his visions and plans more than realized, he saw a city of thirty thousand inhabitants, and manufactories larger than any in the world. Mr. Saunders died in 1872, aged seventy-six years. He married a daughter of Mr. Caleb Abbot, of Andover. Two of his sons are residents of Lawrence,— Daniel Saunders, Esq., and Caleb Saunders, counsellors at law. The former was born in Andover, graduated at Harvard College, 1844. He has been mayor of Lawrence and representative to the Legislature. The latter was born at North Andover, graduated at Bowdoin College, 1859. He was mayor of Lawrence, 1877." Pretty laudatory account, right? However, there is another side to the story. The Rest of the Story: The Boston Associates and the Founding of the Essex Company Notwithstanding the glowing account of Daniel Saunders, above, other accounts are less lauditory. The Lawrence History Center, in their description of the founding of the Essex Company, provides a probably more balanced synopsis: "As early as the mid 1830s, a small manufacturer turned land speculator, Daniel Saunders, began buying thin strips of land on either side of the Merrimack River between Lowell and Andover/Methuen in order to be able to control water power rights. He worked with his son, Daniel Saunders, Jr., his uncle, J. Abbot Gardiner, and John Nesmith. They established the Merrimack Water Power Association and then approached Samuel Lawrence, brother of Amos and Abbott Lawrence, both major manufacturers and part of the later-named Boston Associates. Samuel Lawrence reported to his brothers and to other manufacturing leaders, most prominently Nathan Appleton and Patrick Tracy Jackson. A number of the Boston Associates bought out Daniel Saunders and the others and formed the Essex Company. They kept Daniel Saunders on for a period to continue as a land agent." In other words, Saunders had literally nothing to do with the construction of the Great Stone Dam, which along with its canals and other waterworks, allowed Lawrence to exist, and presumably received none of the wealth of the Essex Company, having sold out his land rather than receive equity in the new company. Nathan Appleton and Abbott Lawrence, principal investors, by contrast died rich men although by the time of their investment in the Essex Company they were already very wealthy. Appleton gained his wealth, along with his brother Samuel, as a successful trader of dry goods imported from Europe during a risky and precarious time, the Napoleonic Wars when New England vessels were liable to be impounded by either the French or British ships; and then later he and his brother were principal founders of large scale manufacturing in Waltham and Lowell before turning their attention to Lawrence. I could not find any indications of the wealth of Nathan, but his brother and business partner was worth $1 million when he died in 1853, the equivalent of billions today. He endowed a lot of things at Harvard and Amherst College. Abbott [two t’s] Lawrence was even more prominent, becoming an unsuccessful candidate for Vice President on the Whig ticket and then American ambassador to Great Britain. He endowed the Lawrence Scientific School at Harvard, Lawrence Academy in Groton (previously known as Groton Academy, not to be confused with the much later-established Episcopal Groton School) and the Boston Public Library. (For a bit more about the Essex Company, see the entry under the same name in the Glossary.) |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed