A Quote by the “other side” (the French moving down from New France in Quebec and Arcadia)12/30/2017 “The Indians tell us of a beautiful River lying far to the south, which they call Merrimack."

^Sieur de Monts^, Relations of the jesuits, 1604.” Excerpted From A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers By Henry David Thoreau

0 Comments

A statue of a saint stood benevolently on the widow-shelf surrounded by plants basking in the sunlight. He was about ten inches high and composed of a dark brown, heavy, rough-cast metal. “Who is that?” I remember asking my mother, when I was about five years old. We learn so much about our world at our mother’s knee. I was a big beneficiary of having a teacher for a mother. “St. Francis of Assisi,” she told me. “My favorite saint,” she added, “along with Teresa the Little Flower.” Who was this St. Francis, hand raised, looking down upon us from the shelf? The impression I got of him, from my social-justice pursuing, liberation theology-espousing, National Catholic Worker-subscribing parents, was of a barefoot, soft-talking, sentimental, free-thinking, anti-authoritarian, tree and animal hugger and social activist. “He loved the animals, and the children, and most of all the poor,” she told me. Soon we were supplementing our Sunday worship with journeys with men and women who strove to live like St. Francis. The Christian Formation Center was founded in the late 1960s next to the St. Francis Seminary on River Road, West Andover, near the Tewksbury town line amid expansive fields and lawns that had once been a dairy farm. Down the slope, the Merrimack River ambled in the distance. The seminary there trained Franciscan priests from 1930 until 1977. The grand, colonial-looking building of the seminary was finally torn down last year to make way for high-end senior housing. Across the street stood the monastery of the sisters of Poor Clare, a female monastic order named after St. Clare of Assisi (1194-1253), the first follower of St. Francis of Assisi (1182-1226). The female Franciscans, nuns, and the male Franciscans, monks and priests, pursued their “formation” into the Franciscan way, alongside “secular” Franciscans, laity who were neither monastic nor clergy. And this is where the Christian Formation Center came in. Formation took many decades, and they worked together at attempting to achieve perfection into the ways of St. Francis. In contrast to the seminary and the monastery, the formation center was a modern structure, set way back from the road among the fields. It was supposed to offer alternative forms of religious expression, albeit within the teachings of St. Francis. Remember, this was the golden period after the reforms of the second Vatican Council, when modernization and making the Church more relevant to the times was the order of the day. Pope John XXIII, who had ushered in Vatican II, had himself been a Secular Franciscan before he became a priest, living an idealized life of poverty and holy contemplation as worked for the poor. Unlike our local church, St. Augustine’s on Ames Street in Lawrence, the Christian Formation Center had no pews for Mass. Seating was auditorium-style, with individual seats arranged in a curvature around an altar that was more like a central performance stage. I think kids sat cross-legged on the floor in front, where the priest and assembled clergy fawned over them. Fully-robed Franciscan priests and brothers walked the outdoor gardens and breezeways, and, when it was time for Mass, they mounted performances of tambourines, acoustic guitars and folk melodies, along with the nuns. We would regularly sing Michael Row the Boat Ashore when we attended Mass there. (In case you don’t know this song, is is a Negro Spiritual that was popular in the civil rights movement and among left wing activists.) These were no crusty parish priests, giving tired homilies and leading the traditional choir. Apparently, the Christian Formation Center sought to attract non-Catholic Christians to its worship, either in an ecumenical outreach that was in the spirit of the times, or as part of some kind of subtle Catholic proselytizing, I don’t know. The whole zeitgeist of the service was quite different from the other Catholic churches where I had attended worship. For one thing, there was speaking in tongues, and a lot of Catholic Pentecostals. Are there Catholic Pentecostals anymore? Other mounting was also going on. As my mother tells it, the Seminary closed in 1977 shortly after we started going, “because a bunch of the nuns got pregnant by a bunch of the seminarians and they all left the religious orders to get married.” I have no idea if it’s true, but we did stop going to the Christian Formation Center by about 1980 if memory serves me. As a secular formation center not tied to the clergy, it could in theory continue despite the closing of the seminary…and the nuns are still there, although they have a small, modern monastery now. Their old facility was torn down to make way for luxury housing, although the Christian Formation Center building survives to this day as a private school for autistic children. Anyway, within a few years, the entire tone of the Church changed. Although there was no return to the Latin Mass, within the Church the social justice trends of the 1970s gave way to the sexual politics of the 1980s, as Pope John Paul II led a traditionalist backlash. The last time my mother set foot in a church for Mass, other than for funerals or weddings, was when my younger sister had the sacrament of penance (first confession) at St. Augustine’s in 1984. After the CCD teacher repeatedly gave lessons on the place of women (in the home, subservient to men), my mother walked up to him after class to give him a piece of her mind. Things in her church had been changing for some years, and this must have been the last straw. She never went back to Mass, although she still has her statue of St. Francis looking over her in the kitchen. Above: Photo of the Melmark School, River Road, Andover, Mass., the former Christian Formation Center. Photo source: Melmark School website.

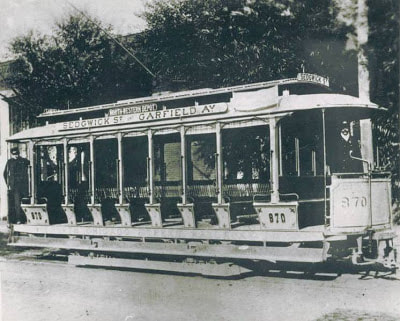

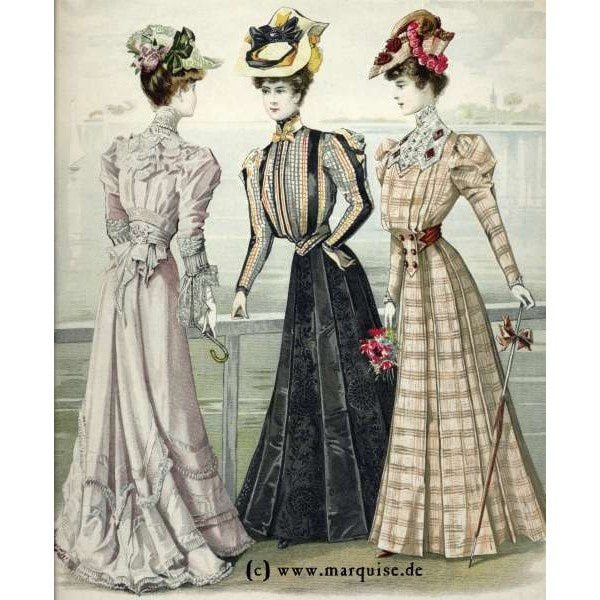

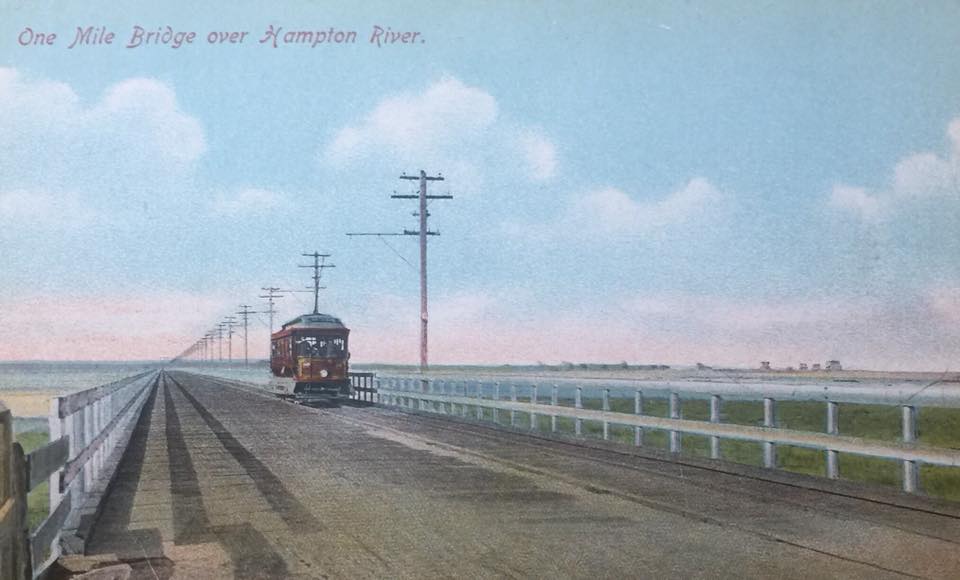

Below: A more expansive view of the facility when it was built. For many decades in Lawrence, from the 1920s through the 1960s, apparently nobody gave any historical significance to the 1912 strike, called the Bread and Roses Strike by some historians. However, by the time I was growing up in Lawrence in the 1970s and 1980s, and textile manufacturing was long dead and gone in the area, the following narrative became popular, not only to explain the strike but to explain the textile industry: Once upon a time, there were some greedy mill owners, who made a lot of profit by exploiting textile workers. The workers had a strike in 1912. They won. Wages increased, and inferior living standards were exposed, making living standards better for everyone. Everything was hunki-dori until after World War 2, when the greedy mill owners decided to move production to the American South where there were no unions. The mills disappeared. The end. A rousing story for sure. But I can't help but be a skeptic and a cynic. I investigated. I questioned the prevailing narrative. It turns out there are potentially a bazillion things wrong with this narrative. The problems have to do with all sorts of things: the misunderstanding of who the "mill owners" were (answer: blue-haired ladies on Beacon Hill with trust funds); the numerous strikes of the time, of which the 1912 Lawrence strike was but one (and a largely insignificant one except for its excellent immigrant participation); massive immigration from Southern Europe in the preceding fifteen years and the subsequent backlash that led to the closing of America's borders in 1920; etc. I'll save my numerous specific critiques of the Bread and Roses narrative for later blog posts. The key point I would like to make here is more basic: nobody these days who pays attention to the history of textile manufacturing in the Merrimack Valley seems to see the story right before their eyes. It is a story that explains the whole arc of the American Woolen Company, from its founding in 1899 to its ultimate demise in 1954. The lost story is this: the company basically only produced one thing, worsted woolen fabric. Miles and miles of it. Every year. For example, in 1912, the year of the strike, it produced 2 million square feet of worsted woolen cloth in Lawrence alone. And the company had production in numerous other New England cities. Fine. However, success does not come from production, it comes from sales. No matter how much production a company has, it is successful only if it can sell its goods. And who was buying most of the cloth by the early 1900s? Women. By the time the American Woolen Company was founded, the epicenter of fashion and clothing was the so-called Garment District of New York City, also known as the Fashion District, where fabric was turned into fashion. Textile companies lived and died by what they could sell there. From its inception, the American Woolen Company had its biggest sales office in New York City. In 1909, a few years after constructing the gigantic Wood Mill and Ayer Mill in Lawrence, the company constructed an impressive office in New York on the corner of Park Avenue South and 18th Street, dedicated to selling its product to the fashion houses and sweatshops of New York. Below: The American Woolen Company sales office near the Garment District, built 1909. At 19 stories, it would have been among the tallest buildings in New York at that time. Things were indeed hunki dori for a while. The strike occurred when confused immigrant workers spontaneously walked out on January 11, 1912 after their pay packets were short 3.57%. The pay was short, however, because the previous week they had worked 54 hours instead of 56 hours due to a progressive piece of Massachusetts legislation that reduced worker hours. At the end of the day, when the company acquiesced, the workers got a 15% raise and profits weren't affected. So good for them. The problem occurred later, in 1926, when fashion changed dramatically and demand for worsted wool plummeted for good. Rather than explain what happened in words, I'll illustrate: Before the decline of the Company: Women got around in this kind of transportation (a drafty open-air trolley): And they wore this kind of fashion: (warm woolen dresses that covered head to toe) Worsted wool cloth was essential. However, throughout the 1920s, the automobile was replacing the streetcar as the primary means of transportation. And automobiles had heaters, especially after the mid 1920s. Clothes could now be made of stylish light fabrics such as rayon, instead of stodgy worsted wool. So by 1926, women wore this kind of fashion instead (made of synthetics such as rayon): It would not be possible to wear such an outfit in a drafty open-air streetcar! Luckily, there was a new form of transportation, the motorcar. The automobile is ineffably linked to 1920s women's fashion, because it made the fashion possible. This is why when you see a photo of a woman in the late 1920s, wearing a skimpy synthetic dress, she is standing next to or riding in a car: without the car and its heater, she simply would not be able to get around dressed like this! Above: advertisement for aftermarket automobile heater, 1922. By 1929 with the advent of the Model A Ford, heaters were standard, along with that newfangled invention that changed mass culture, the radio. Below: typical flapper attire, made of synthetic fabrics. The monthly publication of the National Women's Trade Union League of America, an offshoot of the American Federation of Labor, noted in 1927: "Because the American woman isn't wearing those voluminous woolen garments any more, the woolen industry is suffering a hardship. An abnormally poor demand for woolen goods, coupled with a decline in raw wool prices, last year caused an operating loss of over two million dollars to the American Woolen Company, according to its 1926 annual report." In response to the massive changes in the textile market wrought by the motorcar, did the executives of the American Woolen Company respond by developing their own polyester and rayon production sites? No. Instead, they continued to produce miles and miles of worsted woolen cloth, even though demand (and prices) had dropped for good. A company can make a profit two ways: by making something that's better, newer fresher thus commanding a high profit; or making something that's cheaper, by squeezing production costs. After the loss of 1926, which put the American Woolen Company on the front of Time Magazine and arguably contributed to the suicide of William Wood, the founding president, the company henceforth pursued low costs rather than high value. Thus began the long slow demise of the American Woolen Company. It is no coincidence that the highpoint of Lawrence's population was the mid 1920s, when it was over 90,000. As jobs were reduced as a result of slowing production, workers moved away. The depression was a tough time, and the company was arguably only saved by the massive governmental orders from World War II and the Korean War for woolen cloth for military uniforms and blankets. However, demand had decreased so much and the prices for worsted wool had dropped so much, that if they wanted to stay in business at all making woolens instead of more exciting stuff, they had no choice but to chase low prouction costs for their low-value product. Hence the moves in the 1940s and 1950s to the South, followed by moves overseas. Imagine if the executives had innovated instead? However, that would have meant reinvesting the profits into new machinery, new technology, instead of paying high dividends every year on the preferred shares. Unfortunately innovation did not have the support of the trustees of the various Massachusetts trusts that owned the preferred shares on behalf of various old money families. Typically for such families, a great grandfather had originally locked up his capital - vast amounts of wealth made in the days of the clipper ship and the spice trade - into manufacturing companies that then got combined into the American Woolen Company. Rather than entrust his wealth directly to his heirs, who might squander it, it had been placed in trust. Boston is the original home of “asset management”, as it is called now, thanks to the widespread practice of locking family wealth into trusts where it would then be managed conservatively. The trustees did not see it as permissible to cut off the steady flow of dividends to their fiduciaries. (Which gets me to a tangent: in the 1970s, a small Lawrence-based textile manufacturer, Marlin Mills, that struggled on, did innovate, by inventing a warm, highly insulating, water-resistant cloth made out of recycled plastic fiber, called fleece. They marketed it under the brand Polartec, and it became the standard athletic wear used by high-end manufacturers of athletic clothing such as Patagonia, especially for cold-weather sports. Unfortunately, Marlin Mills did not bother to patent this great stuff they had invented so they could lock in long-term gain for their innovation. Instead, copycat fleece manufacturers quickly emerged, and the polartec cloth quickly became a commodity just like worsted wool had become a commodity. The company went bankrupt twice after trying to maintain production in Lawrence and now has moved production to Asia). So even if a company innovates to stay profitable, which is what the American Woolen Company should have done, it also has to take steps to protect its innovation, or it will suffer the fate of Polartec. PS: I didn't come up with this theory about the link between automobiles and their heaters, women's fashion, synthetic fabrics and the decline of the American Woolen Company. I got it from Frederick Zappalla, "A Financial History of the American Woolen Company," unpublished M.B.A. thesis, University of Pennsylvania, 1947. I have never seen this piece cited anywhere, so am not sure many other people have read it. ”Complexity, ambiguity and paradox may be sweet nectar for historians, but not necessarily for a broad public that tends to prefer grand generalizations, sound bites and contemporary categories into which to shoehorn historical figures. “ - Carlos Eire, New York Times Book Review, December 24, 2017

Photo below: Howard Phillips Lovecraft, 1934. Source: Wikipedia“Now that time has given us some perspective on his work,” says Stephen King, “I think it is beyond doubt that H. P. Lovecraft has yet to be surpassed as the twentieth century’s greatest practitioner of the classic horror tale.” (quoting a 1995 article on H.P. Lovecraft in American Heritage Magazine)

Who was H.P. Lovecraft? From Providence, R.I., he was a weirdly eccentric amateur author of outlandish horror tales. In 1936, Lovecraft died of cancer at age forty-six, barely known outside of the fans of the United Amateur Press Association, of which he was president. A few of his stories were published in Weird Tales and other pulp publications of supernatural horror tales, but he died basically penniless and unknown. “Lovecraft explored [his] sense of cosmic alienation in the loosely connected stories composing what would later be called the Cthulhu Mythos. ‘All my tales,’ he wrote in 1927, ‘are based on the fundamental premise that common human laws and emotions have no validity or significance in the cosmos-at-large.’ The universe as revealed by modern science had no place for ghosts and vampires, the stuff of pagan legends and traditional supernatural fiction. But Lovecraft saw room enough for other horrors in the great gulfs of time and space.” “‘The Call of Cthulhu’ and the other stories in the mythos deal with races of beings from other worlds and other dimensions who once ruled the earth, warred with one another, and now bide their time until they can regain ascendancy. Lovecraft created an elaborate fictional New England for the Cthulhu stories, including the eerie coastal town of Innsmouth [based on Newburyport], the accursed village of Dunwich [based on the western Massachusetts town of Athol], and “crumbling, whisper-haunted Arkham,” [based on Haverhill] home to the unwholesomely curious scholars of Miskatonic University [supposedly Haverhill’s Bradford College, founded 1803 closed 1999]. (From the American Heritage Article) Since the time of his death, H.P. Lovecraft has developed a huge following of fans, called Lovecraftians. They obsessively comb over Lovecraft’s stories, manuscripts, memorabilia and any other document or place that can link them to the object of their obsession, Mr. Lovecraft himself. Lovecraft was a prolific letter writer. In his lifetime, he wrote 100,000 letters totaling around ten million words!! His correspondence, which survives as a collection at Brown University in Providence, R.I., allows his fans to trace his every step. His travels often took him to the Haverhill area, because one of his first editors lived there. This was a colorful character named Charles William Smith, publisher of an amateur fiction magazine called Tryout. A number of Lovecraft’s first published stories appeared in Tryout, which unfortunately had a minuscule circulation. Whenever Lovecraft was Haverhill in the 1920s, he made trips to the surrounding towns, including Amesbury, Newburyport, Salem, Marblehead, Ipswich and Portsmouth, N.H., among others. Because of Lovecraft’s significant travels in the Lower Merrimack Valley, and the propensity of fans to want to retrace his steps, the librarian of the special collections at the Haverhill Public Library sought a guide to the local Lovecraft sites. David Goudsward, Haverhill-born historian and genealogist who is apparently most famous for a book about mysterious Neolithic stones in North Salem, New Hampshire, stepped in and wrote this book. “[W]e were originally envisioning a 6- to 8-page booklet” says Goudsward in his preface, but “we both underestimated the number of locations in the Merrimack Valley that merit mention.” His 192-page [!] book provides a blow-by-blow account of Lovecraft’s travels in the region along with significant contextual explanation about developments in Lovecraft’s personal life and writing career, as well as a number of helpful appendices. I learned for example that Lovecraft made exactly one trip to my hometown of Lawrence, on August 24, 1934, when he left his valise on the Haverhill trolley and had to go to the lost-and-found office in Lawrence. Rather than summarize Lovecraft’s ramblings over the area, however, I will instead try to convey to vision and understanding of the region propounded by his stories and his correspondence. He is completely enamored by anything related to colonial America, and resolutely hates urban areas (although he lived in New York for much of his adult life) and immigrants, including Jews (even though his wife for six years, Sonia Haft Greene, a department store manager who supported him financially, was Jewish). He also apparently was highly squeamish about sexual intercourse, which might explain his numerous stories involving frightened men descending into cold rocky caverns and crypts, the walls teeming with slime. He also had a low estimation of the residents of many of the economically depressed areas he visited, from rural Athol to inner-city port Newburyport. For his story The Shadow Over Innsmouth, Lovecraft bifurcated the things he liked about the place from the things he detested, collecting the latter in a made-up town called Innsmouth that exists next to Newburyport. In his story, “Newburyport is epitomized by the library, the historical society and High Street,” explains Goudsward. “Innsmouth is represented by abandoned shipyards and rotted docks along the Merrimack and ramshackle clam digger huts of Joppa Flats.”[Now Plum Island] The plot synopsis of Shadow over Innsmouth in Wikipedia is this: The narrator has a hard time getting any information about Innsmouth from the Newburyport residents, or even getting to Innsmouth. Finally, the narrator finds Innsmouth to be a mostly deserted fishing town, full of dilapidated buildings and people who walk with a distinct shambling gait and have queer narrow heads with flat noses and bulgy, starry eyes. The narrator meets Zadok, who explains that an Innsmouth merchant named Obed Marsh discovered a race of fish-like humanoids known as the Deep Ones. When hard times fell on the town, Obed established a cult called the Esoteric Order of Dagon, which offered human sacrifices to the Deep Ones in exchange for wealth in the form of large fish hauls and unique jewelry. When Obed and his followers were arrested, the Deep Ones attacked the town and killed more than half of its population, leaving the survivors with no other choice than to continue Obed's practices. Male and female inhabitants were forced to breed with the Deep Ones, producing hybrid offspring which have the appearance of normal humans in early life but, in adulthood, slowly transform into Deep Ones themselves and leave the surface to live in ancient undersea cities for eternity. He is told to leave immediately and is warned that government investigators who pry too deeply disappear. He dismisses the story. However, he is then told that his bus is experiencing engine trouble, and he has no choice but to spend the night in a musty hotel. While attempting to sleep, he hears noises at his door as if someone is trying to enter. Wasting no time, he escapes out a window and through the streets while a town-wide hunt for him occurs, forcing him at times to imitate the peculiar walk of the Innsmouth locals as he walks past search parties in the darkness. Eventually, he makes his way towards railroad tracks and hears a procession of Deep Ones passing in the road before him. Against his judgment, he opens his eyes to see the creatures and faints at his hiding spot. He wakes up unharmed. Over the years that pass, he researches his family tree and discovers that he is a descendant of Obed Marsh, and realizes that he is changing into one of the Deep Ones. As the story ends, the narrator is accepting his fate and feels he will be happy living with the Deep Ones. He plans to break out his cousin, even further transformed than he, and take him to the Deep Ones' city beneath the sea. This short synopsis gives you a pretty good idea of how weird Lovecraft’s stories were! His later story, The Shadow Out Of Time, based in Haverhill, is equally weird and ominous. The narrator is possessed by ancient, powerful beings and witnesses marvels of the distant past. Lovecraft fills his correspondence about the Lower Merrimack Valley with references to local authors. For example, although poet John Greenleaf Whittier of Haverhill is best known for his nostalgic poetry about rural New England and his abolitionist works, Lovecraft looks to him for his collections of supernatural New England ghost stories and tales. Lovecraft is also enamored with the highly eccentric wealthy Newburyport resident “Lord” Timothy Dexter, who died in 1806. “You might have heard of Dexter & his lucky speculations,” writes Lovecraft, “attempts to enter society, freakish extravagance, grotesque house & grounds [Dexter’s mansion, which was still standing when Lovecraft visited, was lined with wooden figurines depicting historical personages such as John Jay and Napoleon Bonaparte], ridiculous escapades, hilarious pretensions to titled aristocracy…” According to Lovecraft, one of Dexter’s statues was “of himself, labelled ‘I am first in the East, first in the West & the greatest philosopher of the Western World.’” Lovecraft also references Dexter’s “absurd book called A Pickle for the Knowing Ones” which is the best name I have heard for a book in a long time. Lovecraft writes to a friend: “That book was misspelled & unpunctuated & when people objected to the latter feature, ‘Lord’ Dexter published a second edition (1796) still unpunctuated, but with a page of assorted punctuation at the end of the book, plus the note: 'master printer the Nowing Ones complane of my book the first edition has no stops I put in A Nuf here & they may peper & solt it as they please’ Goudsward’s book is a fascinating tour of the region’s forgotten history, of which Lovecraft was enamored, visiting ancient puritan graveyards all over the region and getting inspiration from the headstones and the names. He makes a passing reference to the Peaslee Garrison House, for example, which I mentioned in another blog post, and other garrison houses such as the Hazen one built in 1720. He is also into other things that interest me, such as Henry David Thoreau’s A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. This book would be worth the read just for introducing me to Lord Timothy Dexter and his saltbox and pepper grinder of punctuation [!], for readers to liberally spread over the words in his book as they see fit. I will have to look into Dexter and give him his own blog entry. Goudsward has done a good job, via his exploration of Lovecraft’s travels, of conveying the richness of the history of the region that lies right before our eyes and that was very visible to an eccentric observer like Lovecraft. Ms. Llana Barber has written the first academic book about Lawrence's postwar transition, from declining milltown to outer-suburban Latino-majority hub. This is a very important book in understanding the recent history and potential future of Lawrence. She has all the pieces needed to tell the story:

She also has some interesting details about recent events that might interest locals. For example:

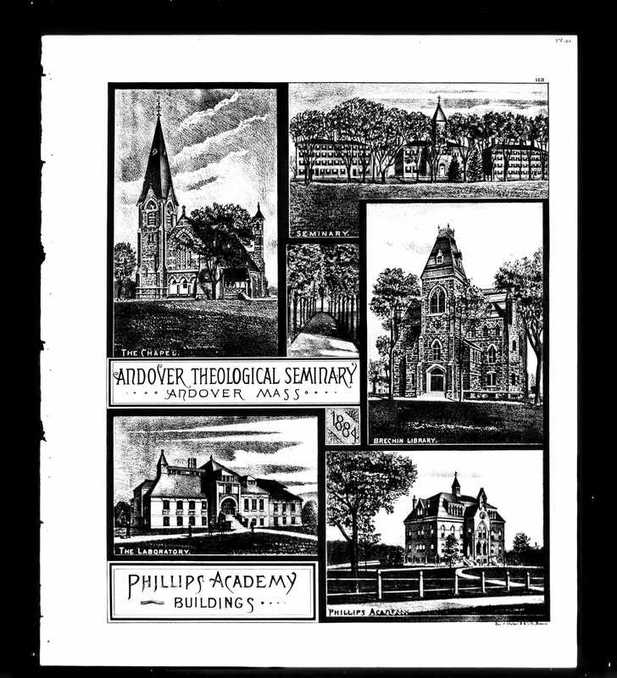

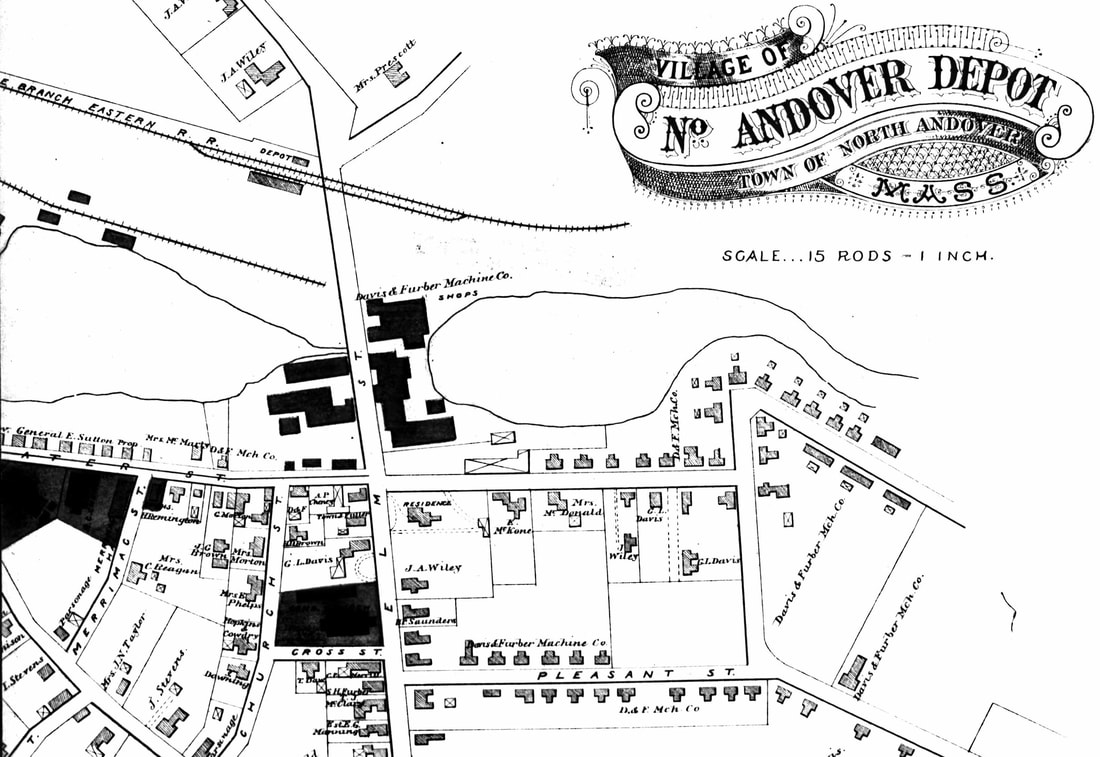

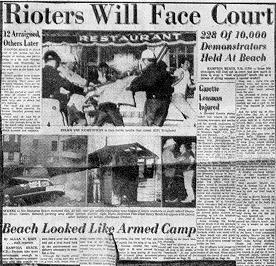

Anyone who is interested in the recent history of Lawrence, or the significance of a sizable Latino-majority city, should read this book. Background of Latino immigration and economic change She comprehensively tells the story of Puerto Rican and Dominican migration to Lawrence starting in the late 1960s. Prior to 1980 or so, most Latino immigrants were Puerto Ricans from New York who were attracted by the perceived safety of Lawrence compared to their New York City neighborhoods, plus the availability of jobs in non-durable goods manufacturing, mainly shoes – Lawrence Maid, Jo-Gal, etc. “In 1970, 83 percent of Lawrence’s employed Latinos worked in manufacturing, compared with only 34 percent in New York City,” she says. Also, Lawrence was perceived as relatively immigrant friendly in light of its history. Industrial jobs, immigrant friendly jobs and relative safeness of Lawrence compared with places like the Bronx were what started Latino immigration to Lawrence. However, by the early 1980s, industrial jobs had largely disappeared and newcomers - this time as many Dominicans as Puerto Ricans - were more attracted by the existing sizable Hispanic population. Her Analysis of the 1984 Riot I actually came across her book while checking my research on the 1984 Lawrence Riot. She has the first published analysis of the riot by an academic that I can find. (There was an unpublished Master's thesis, which is available at the Resources page.) She has an in depth description of the events of August 1984. In my view, the riot was not a very big disturbance, albeit one that local police could not get under control on the first night. It happened less than half a mile from my house with no immediate impact beyond a narrow zone running between Broadway and Margin Street along the base of Tower Hill, across an area of probably less than ten acres. I have suggested that it was more like a large-scale rumble, and not a "riot" in the same sense as the gigantic Detroit riots or Watts Riots which ranged over hundreds of acres destroying a lot of those cities. Even locally, compare the 1964 Hampton Beach riot, which involved up to 10,000 youth battling state police from New Hampshire and Maine and many neighboring towns. She has some interesting little details that I had not heard before: “At 11:00 PM rioters broke into Pettoruto’s liquor store. The Eagle-Tribune reported that at first the two groups [presumably whites and hispanics] fought over the liquor, but then they cooperated to divided it up and share it, after which a ‘lull followed with a lot of public drinking.” She notes dryly, “This odd reprieve could not have been long lived, because by 12:15 AM, the liquor store was on fire.” She also has a graphic description of police action on the second night. “At 10:30 that night, the head of the Northeast Middlesex County [i.e. Lowell area] Tactical Police Force ‘arrived to find Lawrence police pinned down – lying on the ground to avoid gunshots, rocks, bottles and Molotov cocktails.’ An early contingent of forty Lawrence police officers and the regional SWAT team had been no match for the hundreds of rioters who claimed the streets. By 12:30, however, the reinforced police from the surrounding towns and state police from six barracks, marched in cadence down the streets, pushing the Latino rioters in front of them, herding them into the Merrimack Courts (Essex Street) projects, where virtually very newspaper account assumed all the Latino rioters lived.” “Latinos lived throughout the neighborhood, however, and it is highly unlikely that all the Latinos at the riot site lived in the Essex Street projects.” She does point out that “it seems that many more white rioters were arrested than Latinos on the second night,” and that at least a handful of them were from neighboring towns who had come into Lawrence to get in on the action. She also has a very interesting reference to an editorial by Eugene Declercq in the Lawrence Eagle-Tribune (soon to be just the Eagle-Tribune, based in North Andover). “Declercq was one of very few commentators to take a metropolitan view of the riots, one that drew attention to the reality of the region's political economy. He challenged the suburban exemption from responsibility for the region’s poor, an exemption premised on politics of local control that enabled people living in the suburbs to exclude low-income residents as a way of protecting their property values and public services. ‘The cherished property values of the wealthy communities that surround Lawrence are secure because of a system that isolates its poor in cities like mine.’” He added “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free – but make sure they live in Lawrence and not near us.” Quibbles with the Book My biggest quibble is that she often falls back on a stark suburban-urban dichotomy to tell the tale of Lawrence versus its neighbors. While it is true that suburbanization (the building of federally funded highways, Freddie Mac financed suburban subdivisions and automobile infrastructure) led to the decline of Lawrence and other small cities in many ways, it does not follow that Lawrence's suburbs were somehow just Levittowns of single family homes built on farmland and shopping centers, and that Lawrence was just a teeming pit of abandoned factories and squalid tenements. As I tried to suggest in my blog entry about the separation of North Andover from Andover, there were industrialized, higher density areas of Lawrence's neighbors that blended almost seamlessly into abutting Lawrence areas. When I was a young child, my grandparents lived on Harold Street in North Andover in a duplex, on a street that almost entirely mirrored my street in Lawrence, Saunders Street, in terms of housing stock and residential demographics. And in the section of north Lawrence near where I later grew up, the neighborhood blended seamlessly into the abutting parts of Methuen. (The construction of Interstate 495 in the early-1970s probably exacerbated the distinction, as it cuts North Andover off from the Lawrence side of the former neighborhood, and provides a very clear frontier area between Lawrence and Andover). Although she tries to emphasize the urban-suburban dichotomy by regularly comparing Lawrence to Andover, this is somewhat misleading, as Andover was the most rural of Lawrence's suburbs and therefore in the best position for postwar greenfield suburban housing developments, especially because of the fortuitous location of highways and an existing commuter train station into Boston. Because of North Andover's industrial heritage, in contrast, it still had huge manufacturing employers into the 1990s. She does talk about the numerous Hispanics who lived in Lawrence and worked at Western Electric in North Andover in the 1970s and 1980s, thus undercutting her simple urban-suburban narrative. My own theory, which I suggested in my post on the August 1984 Lawrence Riot, was that the increasing dichotomy between Lawrence and its immediate neighbors was exacerbated by the 1982 desegregation of schools in Lawrence's peripheral "nice" neighborhoods. It had the effect of pushing existing residents of those neighborhoods over town lines and destroying the previous integration of those neighborhoods with the abutting neighborhoods of Lawrence's suburbs. She does describe with a lot of good detail how it is impossible to mandate desegregation or mixing of students across town lines. "Thanks to Milikken [a court case], the suburbs were not compelled to participate in any meaningful metropolitan desegregation plan, and none of Lawrence’s suburbs chose to participate voluntarily in such a plan with their nearest urban neighbor. An effort to create a voluntary ‘collaborative school’ in the late 1980s for students from Andover and Lawrence failed after it encountered intense opposition from Andover residents." The project would have been jointly run (and largely state-funded) elementary school designed to admit students from both municipalities. However, except for a passing reference to an early-eighties desegregation plan in Lawrence that "was on the verge of being implemented," she does not talk about the actually internal Lawrence desegregation process and its effects. Her analysis of the flaws of the former alderman system of government in Lawrence is well-done. This governmental structure persisted into the 1990s. "“Most critics focused on Lawrence’s alderman style of city governance. Unlike most cities, Lawrence had no professional administrators to head police, fire, street, or other departments." Its patronage based system meant an overwhelming exclusion of Latinos from city employment, although a voluntary quota system was implemented, targeting 16% in 1977 and going up from there. However, I would argue that the alderman system also had a structural benefit. It led to the existence of "crown jewel" neighborhoods in Lawrence, where most to the resources were concentrated and most of the voters lived who then benefited from patronage jobs. These neighborhoods were the upper part of Tower Hill, of Prospect Hill and Mount Vernon. Between the removal of the alderman system of government and internal desegregation, the crown jewel neighborhoods of Lawrence were basically equalized downward to the level of their poorer, less resourced neighborhoods in the flatlands. Thus, Lawrence lost a significant tax base [something that Barber continuously laments along with Lawrence's increasing dependence on state aid]. As a result of these forces, Lawrence's neighborhoods that previously could compete with similar neighborhoods in North Andover and Methuen were slowly turned into ghettos, starkly cut off from historically similar neighborhoods next door in neighboring towns. The fact that such crown jewel neighborhoods were mainly white (remember that until Hispanic migration, Lawrence was 95% white) misses the point. The point is that these neighborhoods were also of a different socioeconomic status and probably could have been a first stepping point up the socioeconomic ladder for recent Hispanic immigrants. Instead, as a result of the trends I just described, Lawrence effectively became one big self-contained Hispanic ghetto starting in the early 1990s, increasingly bifurcated from its historic neighbors. Conclusion Yet...maybe my quibbles with the emphasis of the story are wrong. Yes, Lawrence effectively became its own little Hispanic ghetto for a couple decades (I am using the term ghetto in the classic sense, as a place separated and walled off where a minority group is enclosed, such as the original ghettos for Jews in medieval Europe). However, Lawrence is arguably now turning a corner, as a completely Hispanic city. As Barber says “In a most basic sense, Latinos saved a dying city.” I agree. (A Long Read) Above: the South Parish Church, Andover, Massachusetts. The current church is the fourth meetinghouse built on the site. Photo by the author. Around the year 1800, a battle began over culture and tradition in the old town of Andover, setting the northern part of the town against the southern part. On the northern side was progressive, liberal enlightenment thinking that came to dominate the more educated classes of eastern Massachusetts in the nineteenth century; on the southern side were old New England traditions that were in danger of being lost. The split was arguably hastened by the much more significant industrialization of the North Parish by the 1840s, with large mills clustered around Cochichewick Brook and a growing area of worker housing, Machine Shop Village adjacent to newly-formed Lawrence; versus the less-industrialized South Parish. In many ways the conflict found in this one town, Andover, encapsulated the competing cultural trends of the first half of the nineteenth century of Massachusetts: Enlightenment versus Puritan; Urban versus Rural. These days, most people seem to be unaware of the somewhat tortured history that led to the separation of North Andover, which is actually the oldest part of the town, from Andover. Brief history of Andover’s parishes The town of Andover was founded in the early 1640s at the tail end of the original Puritan settlement that accompanied the Great Migration. See the Glossary. For many decades after original settlement, the town of Andover stood along the north-western frontier of settlement in Massachusetts, along with its then-near-twin on the northern bank of the Merrimack River, Haverhill. A few miles beyond the northern bank of the Merrimack was wild, forested country inhabited only by native Americans. The first settlement in Andover occurred at the present-day North Andover common, the oldest part of then-Andover. In addition to establishing a meetinghouse and hiring a minister from Harvard – the source of virtually all puritan ministers – a schoolmaster was appointed to teach reading, writing and arithmetic (required by Massachusetts law from 1642 onward). A common was laid out and house lots were provided nearby for convenience and for mutual protection against potential Indian raids. Farm lands were allocated to residents on the periphery of the town. After the original settlement, few houses were built on the common and all further residences were built closer to allocated farmland. Despite the original settlement of Andover in the 1640s near Cochichewick Brook, the population continuously shifted southward. In 1697, upon the death of Andover's second minister, the town agreed in principle to build another meetinghouse that was more convenient to more of the population. After a decade of dispute over proper location, the General Court of Massachusetts became involved, and a "South Parish" was "set off", meaning that, henceforth, residents in the larger, southern part of the town would be assessed separately in support of their own minister and meetinghouse. That first South Parish church was erected slightly to the east of the present-day South Church, while the North Parish built its own new meetinghouse on basically the same location as the previous North Parish meetinghouse. The two Andover parishes then co-existed uneventfully for a century. Such "setting off" was the ordinary course of things. The town of Haverhill, which at that time was enormous compared to Andover, had set off three additional meetinghouses and parishes by 1744 while remaining one town (with the exception of the creation of Methuen in 1725). Despite a history of harmony, however, starting around 1800, a number of social and economic currents ultimately drove the two Andover parishes apart, into near diametric opposition. After half a century of estrangement, they finally divorced in 1855, with the South Parish (plus its recent offshoot the West Parish) taking the name of Andover in exchange for a $500 payment; and the North Parish becoming the town of North Andover. Here is the story of that break-up. New England Congregationalism in the Age of Enlightenment The period following the American Revolution (and arguably all of the eighteenth century) was the Age of Enlightenment. Prominent thinkers, from Voltaire and Montesquieu in France, to David Hume and Adam Smith in Scotland, had shaped the Western intellectual landscape that hitherto had been dominated by theologians. Mankind grew confident in its ability to shape its own destiny, through rational thought and technology. According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “the expectation of the age [was] that philosophy – in the broad sense of the term, which includes the natural and social sciences – would dramatically improve human life.” In New England, Enlightenment thinking shone through the prism of the American Revolution. “Eighteenth century Rationalism under the influence of English philosophers like John Locke became the basis for new religious thought in the same way it had helped free America’s spirit of political independence. Locke defended individual liberty and equality and defended human rights. By 1805, Arminians had revamped Christian theology to conform with the principles of the Age of Rationalism.” From And Firm Thine Ancient Vow: The History Of North Parish Church of North Andover, 1645-1974, by Juliet Haines Mofford (1974). Who were these “Arminians”? In the context of the established congregationalist churches of Massachusetts, these were ministers and their followers who had rejected the harsh predestination of their puritan forbears, as taught by reformation leader John Calvin (hence Calvinism or Calvinist). Instead, they espoused the views of Jacobus Arminius. He was a Dutch reformation leader who had opposed the views of Calvin. We are not chosen to believe, he said (contrary to the Calvinist notion of “the elect”), but instead, all humans are given the power to believe in order then to be chosen by God *if* they chose to believe. Christ furthermore died to save all people, not just the elect, and in fact may not have been divine. (This led to the label “Unitarian” from critics, who wanted to uphold the Trinity of the godhead, Father, Son and Holy Spirit.) Some commentators viewed this shift as a natural consequence of the American revolution. “Most Arminian ministers were staunch Federalists and strong supporters of the politics of Washington and John Adams. Many ministers saw in Washington a symbol of national unity possible under the hand of God’s providence and guidance, and they said so in sermons.” (Again, quoting Moffard.) The Unitarians Begin to Dominate “The thoughtful men who represented the Liberals…were few in number at first and with few exceptions lived under the shadow of Beacon Hill or nearby.” (meaning they were your typical Boston rich liberal elites, I guess) (quoting The History of the Andover Theological Seminary, by Henry K. Rowe (1933)). However, by 1800, Boston’s Congregationalist churches had gone solidly Unitarian, with only two out of fourteen maintaining traditional Calvinist ministers. This led to the formation of Park Avenue Congregationalist Church, so-called Brimstone Corner, which reverberated with Calvinistic sermons about the utter depravity and damnation of man. The thunderbolt for the traditionalists, however, was the fall of Harvard to the Unitarians. Prior to 1800, Harvard college was essentially a training ground for all Massachusetts ministers. All students were a classical education deeply focused on reading of original texts in Greek, Latin, Hebrew and Aramaic, regardless of whether they went on to become ministers. The times they were a’ changing, however. “The tendency of the period was to introduce other studies in place of the older discipline, as science and modern literature became more popular in learned circles than Hebrew and Greek.” In short, in higher education, “Theology lost its position as queen of the sciences.” So, “when Reverend Henry Ware of Hingham was elected to the Hollis professorship of divinity at Harvard College in 1805, New England Congregationalism felt the shock, for it was well understood that Ware was really a Unitarian, and that at Cambridge his influence would be radical.” (All quoting Rowe). The Merrimack Valley is the epicenter of the Calvinist response – Andover and Newbury factions The strongest responses anywhere in Massachusetts to the fall of Harvard to the Unitarians seem to have come from Calvinist luminaries in Andover and in Newbury. “Dr. Eliphalet Pearson was disturbed gravely by the liberal trend at Harvard. Pearson was one of the outstanding men of the time in educational circles. He had been the first principal of Phillips Academy and had established its reputation, and after eight years he had been elected to a professorship at Harvard.” (Quoting Rowe.) Phillips Academy, located on a hill in Andover’s South Parish and chartered 1778, was in many ways just another typical “academy” found across that region at that time: a secondary school focused on advanced education for older boys, and sometimes girls, in order to further train them beyond the Three Rs of the schoolhouse –and, in the case of boys, prepare them for the rigors of Harvard. Governor Dummer’s Academy in the Byfield section of Newbury was the precedent for all of these academies of the lower Merrimack Valley, being the alma mater of Samuel Phillips, founder of Phillips Academy. Other similar academies could be found in Groton (now called Lawrence Academy, which for decades also educated girls), Haverhill (the “Haverhill Academy”, the first academy to accept girls, merged with Haverhill High School in 1841), and even in the North Parish of Andover (“Franklin Academy” which closed around 1845 – more on that below). However, from the early days, Phillips Academy did apparently stand out in terms of its academic rigor. “When [Pearson] failed to stem the tide of liberalism [at Harvard] in 1805, and then when Professor Webber was chosen president the next year, Pearson resigned his office and went back to Andover, convinced that something needed to be done to defend orthodoxy. The Academy, of which he was a trustee, cordially welcomed his return and gave him a year's rental of a new house nearby. Then he began to plan for the establishment of a theological institution which should maintain the doctrines of the fathers of New England against the threatening apostasies of the times.” (Quoting Rowe) Meanwhile, downriver in Newburyport, similarly minded leaders were meeting. Technically they were “Hopkinsonians” with slightly less Calvanistic views than Pearson and his cohorts on Andover hill. “Their leader was Dr. Samuel Spring, minister at Newburyport. He had been a pupil of both Hopkins and Bellamy, and had been a recognized leader in eastern Massachusetts for forty years. Leonard Woods, a young minister at West Newbury, was his close friend. Through Spring and Woods three laymen were aroused to an interest in theological education. These were William Bartlet [one t], a successful merchant of Newburyport, Moses Brown of the same town, and John Norris of Salem. They were all men of wealth, and though not all church members they were willing to use their money for religious purposes, and they soon agreed to support the plans for a theological school at West Newbury.” Why was the orthodox response to the Unitarians focused in the lower Merrimack Valley? My theory is that the region had the goldilocks location of not-too-much, not-too-little: on the one hand, it was still part of the original Puritan heartland settled by the Great Migration, and therefore of enough significance to have cultural sway over much of New England, unlike the frontier areas of New Hampshire and western Massachusetts that were still being cleared; yet, on the other hand, it was peripheral enough not to have fallen completely under the cosmopolitan influence of turn-of-the-nineteenth-century Boston, which was increasingly becoming a global port through which flowed the wealth of international trade via world-renowned Yankee merchant ships. Below: Andover Theological Seminary 1884 Founding of the Andover Theological Seminary After significant negotiation, the Pearson wing and the Woods wing agreed to form a theological seminary in Andover next to the site of Phillips Academy, sharing the same Board of Trustees as the academy. Because the two factions could not agree on the wording of their creeds, there were two sets of founding documents for the Andover Theological Seminary, one for the orthodox Calvinists and one for the Hopkinsonians. They were however unified in their antipathy toward Unitarians. On the orthodox side, it was provided that every professor must at the time of his inauguration solemnly promise to maintain and inculcate the Christian faith as summarily expressed in the Shorter Catechism [a standard statement of belief of early puritans] "in opposition not only to Atheists and Infidels, but to Jews, Mahommetans [i.e. Muslims], Arians, Pelagians, Antinomians, Arminians, Socinians, Unitarians, and Universalists, and to all other heresies and errors, ancient or modern, which may be opposed to the Gospel of Christ, or hazardous to the souls of men." Furthermore, every professor must repeat this declaration in the presence of the Trustees once in five years. Getting the Hopkinsonians on board was important because of the wealth they brought. The main building was named Bartlet Hall in gratitude for the gift of their main benefactor (it exists today on the campus of Phillips Academy and has been renamed Pearson Hall). The Hopkinsonians were thus allowed to have Associate Statutes that existed alongside the institution’s charter documents, and every occupant of a chair endowed by the Hopkinsonians “should be a Hopkinsonian.” “The establishment of the Seminary was a significant event in American church history. The union of the two theological groups of conservatives in the Seminary proved an effective counterpoise to the Unitarian trend in Congregational circles. Naturally the Liberals were not pleased. The Harvard attitude was not friendly. Woods reported to Farrar in 1807 that there was ‘loud murmuring and reproach and imprecation.’” (Rowe) “ANDOVER [Theological Seminary] was founded for the distinct purpose of preparing men for the parish ministry. At that time the prestige of the Trinitarian Congregationalists was at stake. The Unitarians had the advantage of Harvard instruction and the Harvard reputation. Unless the Trinitarians could establish a theological school that would attract young men of ability, and year after year could supply the Congregational churches with orthodox leaders who were able to measure swords successfully in doctrinal controversy when need arose, they would be worsted in the competition of the two theological parties.” It should be noted that, “in a legal sense the new Seminary at Andover was the theological institution in Phillips Academy, but it was so distinct in faculty, buildings, and funds as to be actually a separate school.” (Rowe) “It soon eclipsed Phillips Academy in endowment, buildings, and reputation. A few years after its founding, it included two large brick dormitories--the present Foxcroft and Bartlet Halls—with a chapel and recitation building...In addition, a number of homes had been constructed for the Seminary professors, the most im pressive being the present Phelps, Pease, and Stuart houses. By contrast, Phillips Academy had one wooden classroom building and a modest house for its principal.” (From Youth from Every Quarter: A Bicentennial History of Phillips Academy, Andover by Frederick S. Allis, Jr. (1979)) In sum, the essential institution for defending orthodox congregationalism was founded on a hilltop in the southern part of Andover, which some in the North Parish of Andover then called “Brimstone Hill.” The Seminary – the first school in America for training ministers that was not part of a college – was technically in the South Parish, but had its own independent congregationalist church. The Seminary exercised significant sway over the philosophy of the nearby South Parish church, and then the West Parish church, which was set off from the South Parish in 1824. Both were avowedly Trinitarian (and thus, at the time, Anti-Unitarian). They are still Trinitarian, to the extent such distinctions are relevant in modern society. Meanwhile, the North Parish of Andover was going in a very different direction As you might have guessed, the members of the North Parish generally considered themselves more forward thinking and enlightened. The South Parish handbook of 1859 went out of its way to label an early North Parish minister, Reverend William Symmes, who was ordained in 1758 and died in 1808, as an “Arminian” although such label is debatable. Another historian of the region, Sarah Loring Bailey in her 1880 history of Andover, called Symmes “the last of the old-time ministers.” It is definitely true that when a new minister was sought for Andover’s North Parish in 1809, being too Calvinist led to a rejection. “When, after the death of Dr. Symmes, the parish came together to ordain the minister whom they had called, the Rev. Samuel Gay, it proved that the views of Christian doctrine which he expressed were not satisfactory to all the officers of the church and parish, being more rigidly Calvinistic than they approved. The ordination services were, therefore, broken off.” (Quoting Bailey) Instead, they hired Reverend Bailey Loring who was ordained on September 19, 1810, age twenty-three. Interestingly, he was a graduate not of Harvard but of Brown. Of the four colonial era colleges in New England, Brown was an outlier in that, from its inception, it allowed different religious views (although, having been founded by Baptists expelled from Massachusetts, it was required until 1950 to have a Baptist minister as its president). In my research of the various meetinghouses of the lower Merrimack Valley going back to the 1630s, I have never come across a minister educated at Brown, although two were educated at Yale and one at Dartmouth (other congregationalist stalwarts). Dozens if not hundreds of ministers in Massachusetts prior to 1800 were educated to Harvard. “Mr. Loring was not a Calvinist. His theological education had been under the Arminian school of belief. But, like his predecessors, he was catholic [meaning universal not Roman Catholic] in his sympathies, and maintained throughout his ministry friendly relations with his brethren of various creeds. He continued to exchange pulpits with those of similar tolerant principles, even after the partition walls had been built up between the two divisions of the Congregational order, and when this breaking through was censured by the more dogmatic of both parties.” (Quoting Bailey) He did, however, establish a new covenant between members, one of distinctly Unitarian beliefs. Some supporters of the North Parish side of the story saw a conspiracy against him coming out of the Seminary and the South Parish. Ms. Moffard notes in her 1974 history of the North Parish church that Loring was rejected from the Andover Seminary for incompatible beliefs, and this fact “weighed in Mr. Loring’s favor” when he was ordained by the North Parish. “Bailey Loring was their man, an unmistakable and irrepressible Arminian who was undaunted by the proximity of the new seminary in South Parish.” (quoting Moffard) “The schism began, possibly as early as 1820, when certain members felt that Mr. Loring and North Parish were not satisfying their soul yearnings…they held the belief, not only in Jesus of Bethlehem, a historical teacher [the classic Unitarian view which, by the way, in my book is no longer Christian per se], but in Jesus the Christ, Lord and Savior…Students from the Seminary were often present to lead them in worship.” (Moffard) Eventually, a Trinitarian faction was able to form in North Parish, apparently aided by the Theological Seminary. Their situation was greatly aided by the 1833 disestablishment of the Congregational churches in Massachusetts, which meant that, henceforth, financial support could not come from the parish poll tax; rather, churches had to be dependent on their members, who could live wherever they wanted. On July 24, 1834, the Trinitarian Calvinistic Church was formally organized. On September 3, 1834 the new building was declared. It could be viewed as a mission church from the South Parish: of its members, only one male member was a defector from the North Parish, while 14 came up from the South Parish. This church changed its name to Trinitarian Congregational Church in 1841, and bears that name to this day. The Unitarians in North Parish engaged in no such missionizing, and for the entire 19th century, Andover’s South and West Parishes had no Unitarian church, presumably being under the sway of the Theological Seminary. The existing Unitarian-Universalist church in Andover moved there from Lawrence in 1964. Below: Interior of North Andover’s Trinitarian Congregational Church, built 1865 by the same architect as the 1861 Andover South Parish Church (source: church website) The Cultural Differences Between North Parish and South Parish Illustrated by a Comparison of Academies Pages could be written about the strict, cold demeanor of Phillips Academy and the Andover Theological Seminary. The following gives a flavor of life as a student at the Theological Seminary. Life at the Academy was not that much different apparently. “For exercise the students blasted and cleared away rocks from the Missionary Field back of the buildings, worked on the campus grounds, and rambled about the vicinity. Two students, one of whom became a well-known college professor, used to race each other around a three-mile triangle on winter mornings before sunrise to give tone to breakfast and the day's work. Professor Park, when a student at Andover, arose at 4.30 and walked with another student over Indian Ridge or through Carlton's Woods, practising elocutionary exercises in order to develop his oratorical powers.” (Rowe) The author notes rather dryly “The students do not seem to have been miserable, perhaps because they were seldom idle.” Here is a letter from one Andover student in 1819: “That you may know how much a slave a man may be at Andover, if he will follow the rules adopted by the majority, I will give the order of the day. By rising at the six o'clock bell he will hardly find time to set his room in order, and attend to his private devotions, before the bell at seven calls him to prayer in the chapel. From the chapel he must go immediately to the hall and by the time breakfast is ended, it is eight o'clock, when study hours commence and continue till twelve. Study hours again from half past one to three. Then recitation, prayer, and supper, makes it six in the afternoon. Study hours again from seven to nine leave just time enough for evening devotion before sleep.” Meanwhile, the North Parish had its own academy, the so-called Franklin Academy. It can hardly be more different than Phillips Academy, yet in its heyday it seems to have attracted students from as far and wide as Phillips Academy. “In 1799, Mr. Jonathan Stevens gave land on the hill north of the [North] meeting-house. Subscriptions were made by some of the principal citizens. The academy also received a fund of a little more than eight hundred and seventy-five dollars from the division of the proprietors' money [each of Andover and Haverhill and successor towns such as Methuen had rights obtained from the original settlers, the so-called Proprietors, who had paid money for the deeds from the Indians; by the eighteenth century, it was a separate fund that was slowly depleted as the last of the proprietor land was sold off]. The academy was built in 1799. It had been provided that the school should be for both sexes, and it was the first incorporated academy in the State where girls were admitted. The academy was built with two rooms of equal size, — the north room for the male department, the south room for the female department. A preceptor and preceptress had charge respectively of the two departments.” “The school was incorporated in 1801 as the North Parish Free School, and in 1803, by act of the General Court, the name was changed to Franklin Academy. This school, though now discontinued, had a flourishing life of more than fifty years, and numbered among its members students from more than a hundred different towns, a dozen States, and several foreign countries…”(in other words, on par with Phillips Academy of the time.) “Two manuscript records have been found, one containing the names of the male students from 1800 to 1802, and from 1811 to 1834, the other the names of the female students from 1801 to 1821. The names of the preceptors are nowhere found recorded, and the recollections of the pupils and residents of the town in regard to them are indistinct and often conflicting. The following are such facts as the means of information supply: The first Preceptor was Mr. [presumably the Rev. Micah] Stone, of Reading, a graduate of Harvard College 1790, tutor 1796, student of theology with Rev, Jonathan French, Andover, settled 1801 at Brookfield. Mr. James Flint (Rev. Dr. Flint, of Salem) was Preceptor, 1800-1811.” The student experience at Franklin Academy contrasts markedly with the Calvinistic south parish and Phillips Academy: “The reminiscences of the few who yet remain of the early students of Franklin Academy, are of delightful days. The notions of propriety in the North Parish were then much relaxed from the rigidity of Puritan customs, and many social recreations were permitted to the young folks. These festivities the elders directed and shared.” The Franklin Academy ultimately went out of business, it was said, because North Parish – soon to be North Andover – started providing decent town-led secondary education in the form of a High School. This was also the fate of Haverhill Academy, another early academy. It is not surprising that in liberal North Parish, universal secondary education should become provided for by the town and not by private means. Below: North Andover Depot, 1884 showing Davis & Furber facilities on the Cochichewick Brook. Note the Trinitarian Congregational Church at Cross & Elm The Split The actual split into two towns did not happen until 1855, when the matter was put to a vote. South Parish paid North Parish $500 to use the name Andover, despite North Parish being the original part of Andover. By the time of the split, North Andover had become significantly industrial. Four significant industrial concerns clustered around Cochichewick Brook: North Andover Mills, Scholfield Mills, Sutton Mills and Davis and Furber Machine Company. This area of North Parish was in some ways an appendage of Lawrence. There was even discussion of the entire North Parish becoming part of Lawrence, then a booming industrial city full of promise and on the up-and-up (and in 1877 a small section did become part of Lawrence). It is indicative that, whereas the Machine Shop in North Andover was already connected to Lawrence by public street trolley in 1868, there wasn’t a trolley to Andover until the 1890s, the peak of trolley construction when trolleys ran to every neighboring town. (Source: Maurice Dorgan’s Concise History of Lawrence, 1918). “Though the south village of Andover remained unchanged, the industries of North Andover and the mills of Lawrence were so near that her citizens could not remain oblivious to the changes that were taking place. With a rapidly increasing population, New England was sending her sons to the West to be pioneers like their colonial ancestors, and home mission societies were organizing to take care of their religious needs. [See my review of Yankee Exodus.] The application of steam to railway and river travel facilitated the movement of the population, and people became less provincial as their contacts widened.” Supposedly, the split was led by members of the South Parish. They have wanted to keep their relatively rural, traditional idyll untainted by the newfangled ideas and newfangled megaindustry that typified the North Parish. A description of Andover Hill written in 1856 by a student reflects the desire to maintain the rural idyll despite the encroachment of industry and change: "To the north the eye can travel up to the blue hills of New Hampshire, and only three miles distant stand and smoke the mammoth factories of the city of Lawrence. The whole scenery about is dotted with sequestered villages and snow-white farmhouses. Lowell, Salem, Haverhill, and Boston, are next-door neighbors. On the south is a hedge of railroad; on the east we can almost hear the roaring of the ocean; on the north flows the devious but busy Merrimac; while the west, to say nothing of its home associations, gives us a never-to-be-forgotten sunset. Thus environed, overarched by a deep blue sky, and standing upon ground whose beauty pen and paper cannot paint, Andover is the spot for a seminary. . . . Nearly every house looks like a countryseat, and even the old edifices, which were raised, I suppose, in the last century, have an air of neatness about them, being clothed in the purest white. It is a very wealthy place; but the wealth of the Seminary astonishes me. Nearly every house within a quarter of a mile is owned by the Trustees." Legacy of the Andover Theological Seminary By 1908 when the Andover Theological Seminary departed from Brimstone Hill in south Andover for Cambridge, leaving Phillips Academy to fend for itself again, the world was completely different from when it was founded a century earlier. Both forms of congregationalist religion were dissipated, Unitarian and Trinitarian, as competing protestant denominations planted their roots in New England; and then as Boston elites started defect en masse to the Episcopalians, perhaps conflating their Yankee roots with Englishness and forgetting that the Anglican Church had been the scourge of the puritans. The Seminary itself suffered scorn and mockery in the Boston papers for engaging in a sort of theological purity test for Professors in the 1880s. Its heyday was the period from 1808 to the Civil War. When it merged into the Harvard Divinity School (ironically) it only had three students. Yet it left a gigantic legacy on the intellectual landscape of America, because of the tendency of traditional Congregationalists who migrated out of the puritan heartlands of New England (see my entry on the Yankee Exodus) to establish colleges…and their desire to have intellectually rigorous Andover Seminary men as presidents of those colleges. “It is impressive to call the roll of colleges that invited Andover [Seminary] men to be their presidents. In New England they include Bowdoin and Dartmouth, Middlebury and the University of Vermont in the northern tier of states; Amherst, Smith and Brown in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. In New York were Hamilton, Union, and Vassar. Five were in Ohio: Antioch, Marietta, Oberlin, Western Reserve, and Ohio Female College. Moving steadily westward one finds Andover alumni at Wabash, Indiana, Illinois and Knox in Illinois, Drury in Missouri, Washburn in Kansas, Colorado among the Rockies, and Pomona in California. In a more northerly latitude are Adrian and Olivet in Michigan, Beloit in Wisconsin, Iowa College in Iowa, and Fargo in North Dakota. Howard University in Washington, D. C, Atlanta in Georgia, Rollins in Florida, Fisk in Tennessee, and state colleges in Alabama and Tennessee, gave wide representation to Andover in the South. For good measure the universities of Wisconsin and Kansas should be added. And overseas were Robert College in Constantinople and the Syrian Protestant College at Beirut [later the American University of Beirut].” (quoting Rowe) North Parish Unitarian Church, North Andover, Mass. Photo Source: Wikipedia. Present structure erected 1834.

Daniel Saunders..."founder" of Lawrence, Mass., rube [?] and fifth great uncle by marriage [!]12/17/2017 Above: My home until age 2 1/2, Saunders Street, Lawrence, Mass., circa 1973