|

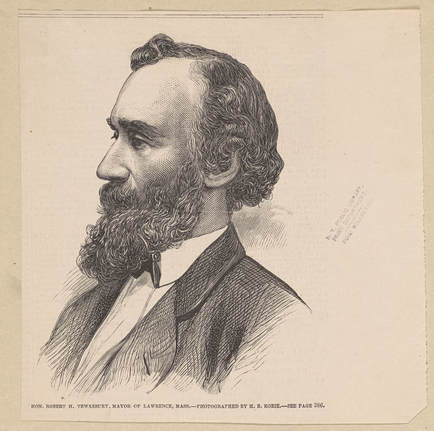

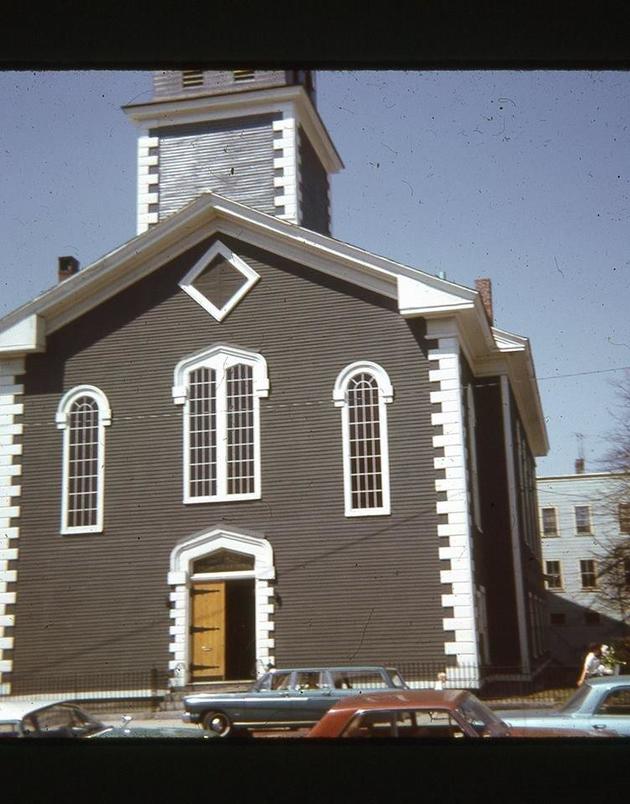

If you’re over forty, you probably remember bumper stickers like this all over Massachusetts: Among persons of Irish descent, support for the Irish Republican Army (IRA) was widespread, even if it was superficial. Somehow it was okay to like Princess Diana and Irish republicans… The IRA story was easy to understand. The British army was an occupying force. IRA men were freedom fighters, naturally fighting for a unified Ireland. British empire, bad. Freedom fighter, good. It’s all very romantic. Almost nobody from the area knows the story of the “other side”, the so-called Ulster Orangemen, who also made the region of Ulster their home. They were fighting for minority rights just as much as the IRA. Below: Logo of the Ulster Defence Association, paramilitary group The history of the Orangemen in a nutshell Ireland was ruled by the English crown starting in the 1500s. In the early 1600s, Scotland was technically still a separate kingdom. The English king had a problem. What to do with all those pesky Scots who lived on his side of the English-Scottish border? They kept trying to rise up against him. Solution: deport them to Ireland. These “Scots-Irish” (Americans like to say Scotch-Irish) were given land and rights in the province of Ulster, which was called a Plantation. They were supposed to raise sheep and pursue other productive ventures. Some of them soon left Ulster and settled the hillbilly regions of the United States. That’s another story. The ones who remained in Ulster had a tenuous relationship with the English powers. They refused to kowtow to the Anglicans who ran everything. Instead, they followed a very Calvinistic form of Presbyterianism. Although they had more rights and wealth than the Catholic population, they were an often-second-class minority within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Below: Political Cartoon from 1913 Regarding Ireland "Home Rule" When Ireland began to break away from Great Britain, the Ulster Scots leveraged their close-knit status as a political force. They won the separation of most but not all of the Ulster province from independent Ireland. The section in which they were a majority remained with Great Britain. The Ulster Scots saw themselves as a beleaguered minority of Ireland proudly clinging to their traditions. The British crown was now their protector, hence their extreme loyalism. The Orangemen One of the big traditions among Ulstermen is a commemoration of the Battle of the Boyne (July 12, 1690). In this battle, Protestant William of Orange, who rule as co-regent with his wife Mary II (hence the reign of William & Mary), defeated the deposed King James II, thus thwarting James’ failed bid to restore Catholicism to Great Britain. To commemorate this victory, Orangemen hold marches. During the “Troubles” of Northern Ireland, from 1969-1998, often these marches were designed to provoke their Catholic rivals, just as republican (meaning pro-Republic of Ireland) countermarches were designed to provoke Ulster communities. Technically, the Orangemen are a fraternal organization, comprised mainly but not exclusively of Ulster Scots (some are descended from English settlers of Ulster). It was technically founded as a brotherhood for all Protestants, in 1795 in County Armagh in Ulster. Below: Typical procession of Orangemen in Northern Ireland, July 12, 2016. PHOTOGRAPH BY Michelle McCarron. What does any of this have to do with the Merrimack Valley?? On July 12, 1875, the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne, a group of self-styled Orangemen held a picnic on the banks of the Merrimack River in Methuen. When they returned to Lawrence by way of steamer to Water Street, they were met a mob of 200 Irish Catholics. A riot erupted, and police fired at the mob. Here is the coverage from the New York Daily Herald: “Lawrence, Mass. – A serious riot occurred in this city to-night, resulting from an outbreak made by a mob upon the members of a lodge of Orangemen returning from celebrating the ‘Battle of the Boyne’ at a picnic at Laurel Grove, four miles up the Merrimac River. Orangemen from Lowell, Woburn and other towns participated at the picnic, which passed off quietly, and no trouble was anticipated when they dispersed for their homes, though some threats had been made in the morning and some of the men carried firearms in consequence. MOBBING THE LADIES About a dozen Orangemen, with ladies and children, disembarked at eight P.M., at the steamer landing on Water street, and started to walk up town. A crowd of several hundred Irish were at the landing and followed them, shouting and jeering. When they arrived in front of the Pacific Mills, the crowd commenced throwing stones, one of the ladies being struck three times and badly hurt. All the party were more or less injured by missiles thrown at them during their half mile walk to the police station, whither they went for protection. Four of the men had on regalia, which particularly incensed the mob. One of the men was severely hurt about the head and had his sash torn from him THE MAYOR JEERED AT On their arrival at the police station word was sent to the Mayor [ed: Robert H. Tewksbury], who soon arrived at the scene and undertook to disperse the mob of men and boys, but without avail; the cries and jeers of the mob drowned his voice. The Mayor, with a squad of police [editorial note: who were probably mostly Irish Catholic!], then started to take the party through the crowd to their homes. SHOWERS OF STONES Essex Street, through which they had to pass, was at this time filled for half a mile with the mob. Showers of stones, bricks and other missiles was [sic] hurled at the party as soon as it appeared upon the street. With the exception of the Mayor every one of the party was hurt. Policeman Gummel was knocked down and badly hurt. James Sprinlow, who was endeavoring to protect his brother’s wife, was knocked down, received a terrible wound in the head from a brick. At the corner of Union and Spring streets the mob made a furious onslaught of the party, when nearly all the police and Orangemen were knocked down. The latter then, in self-defense, drew their revolvers and began firing on them on the mob, who were shouting ‘Kill the damned Orangemen.” THE WOUNDED The firing quickly dispersed the mob, who scattered in all directions. It is impossible to learn the accurate result of the shooting. So far as known no one was killed. Two men, one woman and a boy twelve years old, were wounded; none seriously. Of the Orangemen twelve were wounded by stones and bricks, some of them quite seriously, and four policemen were more or less hurt. COURAGE OF THE MAYOR The riot lasted two hours and a half, and extended over a route of a mile through the most thickly portion of the city. It is the most serious affair of the kind that has occurred since 1852 [sic? Is this right? I thought the anti-Irish riot was in 1854], and is condemned on every hand as most unprovoked. The courage of the Mayor undoubtedly saved many lives.” Below: Robert Haskell Tewksbury (1833-1910), Mayor of Lawrence in 1875 Mary O’Keefe, whom I have written about, condemned the riot. She specifically cited the efforts by Irish Catholic clergy to distance themselves from the events. “And now we come to an event which we are doubtful about mentioning in a sketch of Catholicity in Lawrence for testing as we do, that Catholicity had no share in it. We refer to the ‘Orange riot’ which took place on the 12th of July, 1875, the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne, and was, by an accident, very largely advertised all over the country, and, of course, ridiculously exaggerated. However, lest we should be understood as acknowledging, by our silence, the truth of these reports, we here insert a card signed by the Catholic clergy of Lawrence, and published, at the time, in all the local papers. It expresses not only their sentiments, but those of all others in the city deserving the name of Catholics. “We, the undersigned, Roman Catholic clergymen of Lawrence, desire to publicly make known our condemnation of the riotous proceedings of last Monday evening. We do not consider as Catholics, in the proper meaning of the term, those who participated in the disturbance of the public peace, and who, by their shameful conduct, sullied the fair fame of our city. We teach our people good will towards all men, and we strive, by precept and example, to impress upon them the importance of faithfully observing the laws. We trust that the few ruflians who, under the name of Catholicism versus Orangeism, have created such bad feeling and given rise to so much trouble, may be made to feel the enormity of their crime. – SIGNED W. H. Fitzpatrick, Pastor of the Immaculate Conception Church; J. H. Mulcahy, Asst. Pastor of the Immaculate Conception Church; Jno. P. Gilmore, D. D. Regan, J. A. Marsden, O. S. A., Pastors of St. Mary’s Analysis and Questions What I would like to know: were these marchers really Orangemen, meaning they were really of Ulster descent? I have never heard of any Scots-Irish living in Greater Lawrence. I asked the Lawrence History Center, who have a redoubtable collection of materials related to dozens of different immigrant groups to the area. They have nothing on Scots-Irish, Ulstermen, Orangemen or anything similar. (There was however a large Scot-Irish settlement in Londonderry, New Hampshire - however, this town is probably too far away to have been the source of these marching "Orangemen".) I can’t help but think the march was of anti-Catholic types, of which there were still many (soon I hope to write about the Catholic school controversy of 1888 of Haverhill). But more research is needed. If anyone’s ancestor was a member of the Grey Presbyterian church in Lawrence, it would be great if you could contact me about the origins of your ancestors. Below: First Presbyterian Church (The Grey Church), 315 Haverhill Street(?), Lawrence, Mass.

0 Comments

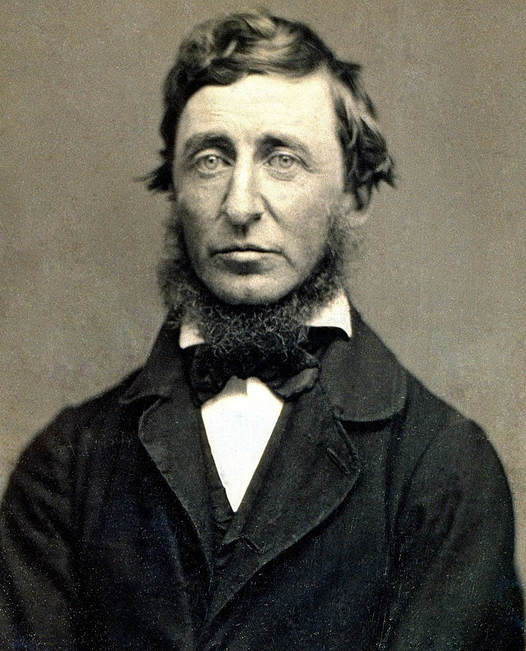

The Yankee Encounter with the Shanty Irish: Henry David Thoreau's Poem "I am the little Irish boy"3/24/2018 I am the little Irish boy That lives in the shanty I am four years old today And shall soon be one and twenty I shall grow up And be a great man And shovel all day As hard as I can Down in the deep cut Where the men live Who made the railroad. For supper I have some potato And sometimes some bread And then if it’s cold I go right to bed. I lie on some straw Under my father’s coat My mother does not cry And my father does not scold For I am a little Irish Boy And I’m four years old. Below: Henry David Thoreau (Source: Wikipedia) The above poem, classified as "doggrel" or a nonsense poem, was written by the famous American philosopher and writer Henry David Thoreau in Concord, Massachusetts in 1850. He wrote it at the height of the Irish refugee crisis, when improverished Irish refugees fleeing the Irish potato famine built refugee camps called shantytowns on marginal land. The newcomers mostly worked at menial pick-and-shovel jobs, building roads and railways. Thoreau kept prolific journals. Through them, we learn something about his encounters with his Irish neighbors living in the woods in a shack, just like he was (although he did so out of philosophical choice, they out of bare necessity). The boy’s name was Johnny Riordan. Thoreau first mentioned the boy in a journal entry of November 28, 1850, when he penned the poem. A few weeks later, on December 21, 1851, he became upset about the boy’s condition: “This little mass of humanity, this tender gobbet [?] for the fates, cast into a cold world with a torn lichen leaf wrapped about him…I shudder when I think of the fate of innocence.” On February 8, 1852 Thoreau finally acted. “Carried a new cloak to Johnny Riordan,” he remarked in his journal. Upon giving his gift to the boy, he gained entry to the Riordan shanty. He wrote in his journal, favorably if very condescendingly, that “the shanty was warmed by the simple social relations of the Irish…What if there is less fire on the hearth, if there is more in the heart!” Thoreau’s friend, philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson, who was also living in Concord and on whose wooded lands Thoreau lived, wrote to Thoreau: “Now the humanity of the town suffers with the poor Irish, who receive but sixty or even fifty cents, for working dark till dark, with a strain and a following-up that reminds me of negro-driving.” A few weeks later, Thoreau wrote back to Emerson positively: “The sturdy Irish arms that do the work are of more worth than oak or maple. Methinks I could look with equanimity upon a long street of Irish cabins and pigs and children reveling in the genial Concord dirt…” In this correspondence, as in his dealings with the Riordan family, Thoreau seems very sympathetic towards his poor Irish neighbors living in their shanties and laboring at building the railroad. And yet…Thoreau was at this very time putting the finishing touches on his masterwork, Walden. In it, he famously and derogatorily denigrates his shanty-Irish neighbor, John Field, for his “inherited Irish poverty” and lectures him for not being able to resist wanting “luxuries” like butter and tea that force him to slave and toil from dawn to dusk, instead of saving his pennies to better his situation. Even better, suggests Thoreau, Field should realize that he should transcend his material needs entirely! And all that coming from a Harvard-educated bachelor who can afford to live in the woods in a shack, not out of necessity but to make a philosophical statement! The poem “I am a little Irish boy”, then perhaps was not meant by Thoreau to be sympathetic, but rather sarcastic. Maybe it's making fun of the boy and the pathetic constraints on his life that have already predestined him to an existence of digging ditches. Nevertheless, the poem can be touching when read in the right spirit. I found this version of it, set to music and sung, that is particularly touching. I hope you enjoy it. PS: At some later point, I hope to write a blog post about Thoreau's journey on a raft down the Merrimack River with his brother, which he covered in his book "A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers" (the Concord River flows into the Merrimack at Lowell).

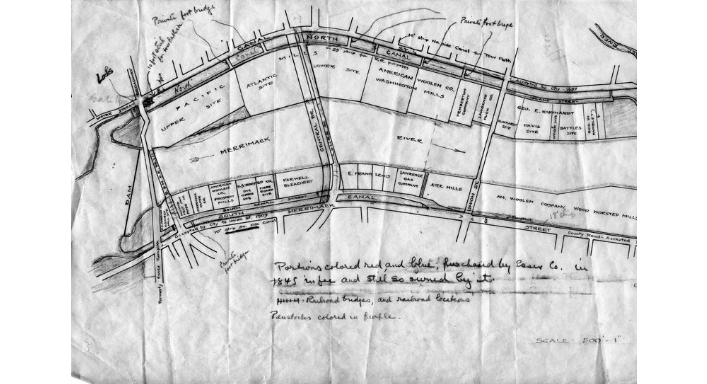

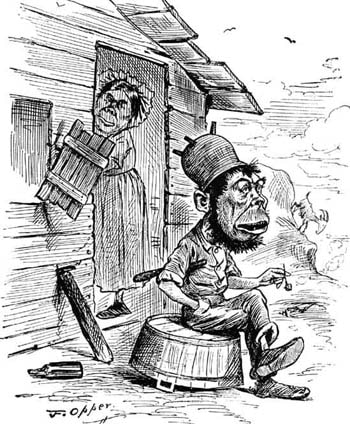

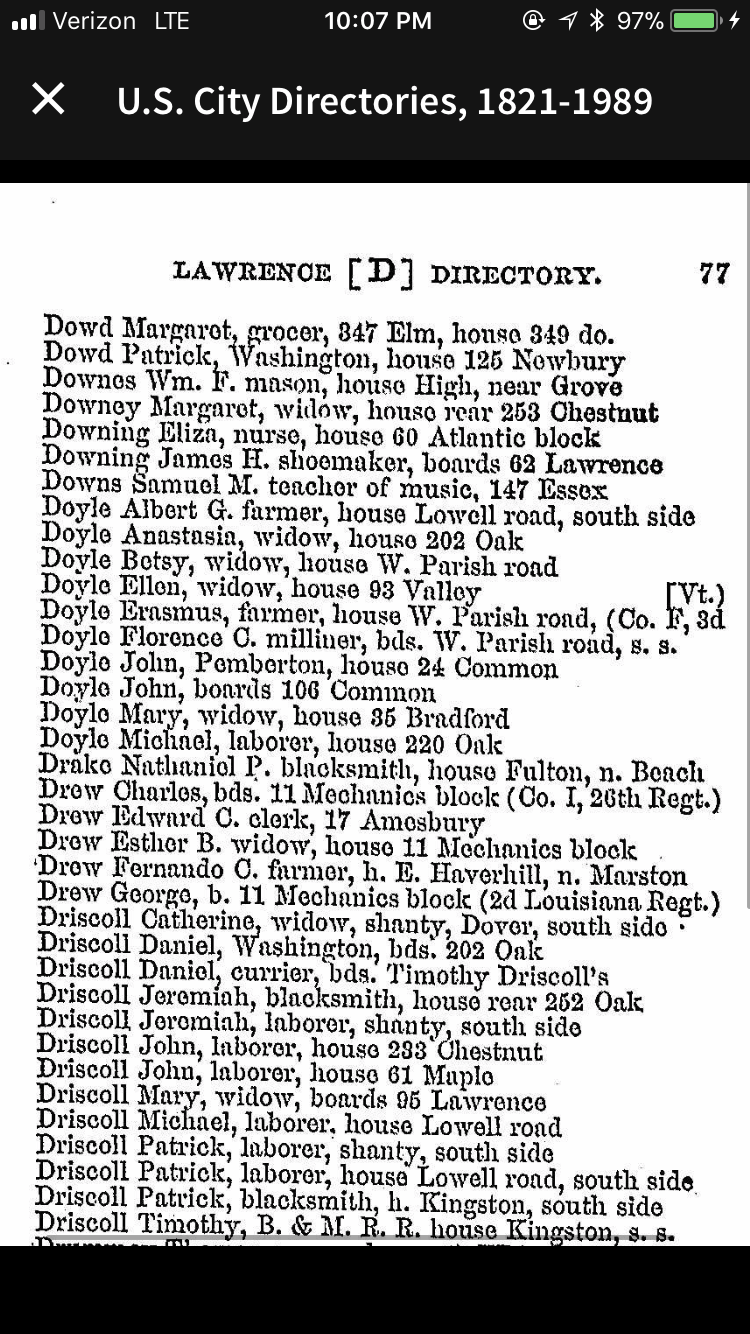

Above: Katherine O'Keefe O’Mahoney, born Ireland 1855, died Lawrence, Mass. 1918 (Source: Lawrence, Massachusetts by Ken Skulski, 1995) The Backstory Before there was Lawrence, there was ye olde New England: clapboard farmhouses, village greens, slow-moving farmers who mended their stone walls and carted their produce to market. This is how things were in 1845, the year Lawrence was founded as a town. Things in 1845 really weren’t all that different from 1645, two hundred years earlier, when the area was first settled by English Puritans in the towns of Andover and Haverhill. The ancient towns were later carved into the towns that we know today – Methuen, Salem N.H. (both formerly part of Haverhill), North Andover (the original part of Andover)…and Lawrence. Sure, the railroad had been introduced a decade earlier, and the Puritans had mellowed somewhat. People were no longer executed for witchcraft or whipped for heresy. But the culture was basically the same as it had been for generations. The original Puritan settlers had come forth and multiplied, cleared the land, built meetinghouses. Some of them went off to sea, chasing whale oil or Far-East silks and spices; or enterprisingly built waterwheels to grind their neighbors’ grain. Some of the local militia boys had gone off to the Battle of Bunker Hill and other early encounters of the Revolution. Basically, however, people farmed, traded, read their King James Bibles, attended meetinghouse, lived and died. Things were homogeneous and consistent, generation after generation. Below: Typical New England farm of the early 19th Century, similar to Bodwell's Farm in what became Lawrence (Source: New England Historical Society) Then, in the second half of the 1840s, two things happened: (1) industrialization and (2) a refugee crisis. Here Come the Factories The fast-moving tributaries of the Merrimack River had always powered waterwheels – little mills that were used to grind grain, saw logs into boards, or run a few looms to supplement the homespun cloth. However, in the 1840s, the mills being planned were different: they would now be on a grand scale. The immense new wealth of the spice trade and whaling was chasing new investments, and could finance endeavors on a previously unimaginable scale. The industrial revolution was underway in Britain and provided the technology. The planned textile city of Lowell was the first example, as we all know, but bigger and bigger factories could be planned. So a group of rich Boston merchant pooled their capital to form the Essex Company. In 1845 this company started to build Lawrence in a backcountry corner of Essex County, smack in the middle of farmers’ fields that had been cleared two centuries earlier. Their project – to build the largest dam in the world across the Merrimack and force its waters down two long canals to power dozens of enormous mills – required a lot of labor, the cheaper the better. Below: Plan for Lawrence showing new dam, canals and plots for water-powered textile mills, 1845 (Source Digital Public Library of America) Here Come the Irish Refugees And who should conveniently show up but a bunch of Irish refugees who could be put to work for pennies a day? These rag-clothed, impoverished, filthy bands of people were escaping the biggest humanitarian crisis of their time. The Irish Potato famine was so severe it killed one third of the people and forced another third to flee. The Famine Irish had arrived on dangerous, unseaworthy “coffin ships” operated by unscrupulous people-runners looking to exploit the desperation of the refugees. A risky voyage across the water was nevertheless preferable to staying in Ireland. Below: A So-Called Coffin Ship Leaving Queenstown (Now Cobh) Ireland, 1848 The Irish migrants crowded the port of Boston, then made their way inland, likely on foot, looking for work. The stream of refugees began in 1847 and did not abate until the mid-1850s. At Lawrence, they formed their refugee camp – the shantytown on the southern bank of the Merrimack – and the men started working on the dam. One of these laborers was my great great grandfather, Jeremiah Driscoll, arrived from Ireland in 1851 at age 29. He worked as a laborer for the Essex Company. His home address in the Lawrence town directory, once the town was big enough to have a directory, was “Shantytown, South Side.” Other Irish built a shantytown/refugee camp on the plains above Haverhill Street, near the Spicket River. A report from 1870 stated that some shanties had to be cleared for construction of the Lawrence reservoir. One of them was 120 feet long, and made of rough boards. It housed 80 people, mostly single men but also a family who built the place and charged the boarders a half penny a day to shelter there. Below: Derogatory Cartoon Depicting Shanty Irish Irish Pride in Early Lawrence Fast forward thirty-five years or so to 1882. Lawrence has grown from a couple hundred residents to 38,000…and around half of them are Irish. Although the town is seven square miles, most folks are concentrated in walking distance of the mills lining the river, spanned now by three bridges. There are by this time over a dozen large textile mills with more being built. The Irish, though largely still poor, have survived massive prejudice and exploitation within a largely hostile Yankee society. What do they do to show their pride? Do they march in a St. Patrick’s Day parade? Hardly – the first proper St. Patrick’s Day parade in Lawrence wasn’t until the 1900s. Go to a Riverdance concert? Listen to the Dropkick Murphy’s? No: they celebrated their Catholic faith by building magnificent churches and then organizing their lives around them. Below: Interior, St. Mary's Church, erected Lawrence, Mass. 1871

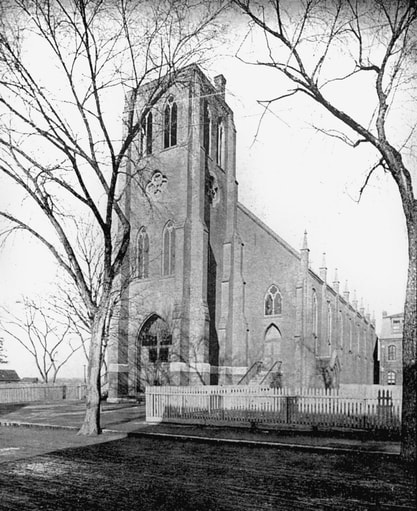

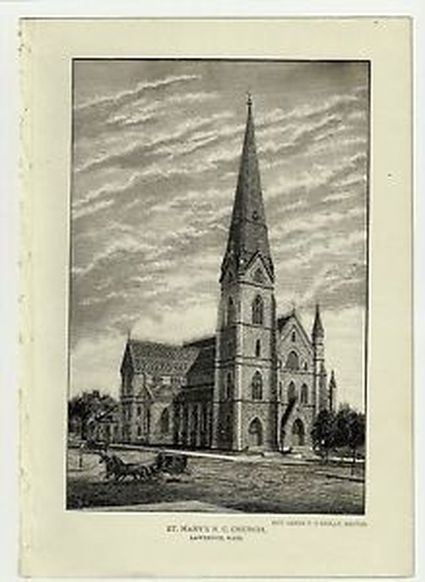

As one observer wrote, the Irish were known to spend their money on beautifying their houses of God before they beautified their own homes. Indeed, in 1882, three grand churches had been constructed of granite and brick in Lawrence – Immaculate Conception on Chestnut Street, St. Mary’s on Haverhill Street, and St. Lawrence O’Toole at the corner of Essex and Union Streets (it was renamed Holy Rosary in 1904 when the new St. Laurence O'Toole was built on East Haverhill Street). Yet at the same time, many Irish in Lawrence still lived in shanties. The last shanty was not torn down until 1894. Above: Immaculate Conception Church, Chestnut Street, Lawrence (Source: Queen City Blog). Lawrence's first permanent Catholic church, torn down 1991.The sense of Irish pride in their Church and its institutions – its grand churches, its rigorous schools, its charities like orphanages and hospitals – is captured in an 1882 book, “Catholicity in Lawrence” by Katherine O’Keefe O’Mahoney. According to Ken Skulski’s history of Lawrence, O'Keefe was “an author, lecturer and educator”. Irish-born, she graduated from Lawrence High School in 1873 (a rarity for girls, especially an immigrant girl), and then she started working there as a teacher. “Robert Frost considered her one of his favorite teachers. She was also among the first Irish-American women to lecture in New England. Her books include A Sketch of Catholicity in Lawrence and Vicinity (1882) and Famous Irishwomen (1907).” She also published a newspaper for Irish-American Catholics in Lawrence and conducted Irish classes there. She died at her Tower Hill home in 1918 at age sixty three. (Source: Ken Skulski’s Lawrence, Massachusetts.) For the about the first thirty year's of Lawrence's existence (until French Canadians started to arrive), pretty much the only Catholics in Lawrence were Irish. Reading O'Keefe's proud descriptions of St. Mary’s Church, you can get a sense of the importance of a magnificent church like this to the community:

Below: St. Mary's Church, Lawrence, Mass. erected 1871 For her, the priests are towering figures, and funerals of priests are the equivalent of a funeral for a head of state. The following is from her description of the 1875 funeral of Father Louis Edge, O.S.A., who built St. Mary’s along with the Augustinian Order. She claims that 10,000 people viewed his body lying in state in his coffin in front of the altar. Note the participation of the numerous Irish social and religious organizations: “Early on Monday morning, crowds began to assemble in the vicinity of the church, awaiting the opening of the doors. The Ancient Order of Hibernians, numbering nearly 150 men, were the first to enter, and to them was assigned the East wing; after them came the Ladies’ Sodality of St. Mary’s Church, with medals and white veils. They numbered over seven hundred, and presented a beautiful appearance. The Irish Benevolent Society, headed by the Lawrence Brass Band, were the next to enter the church. They numbered nearly two hundred, and bore a silken mourning banner; they were seated in the Gospel aisle. Next came the Ladies’ Sodality of the Church of the Immaculate Conception, in white veils, similar to St. Mary’s Sodality; they had been assigned to them the West wing. After them came the Men’s Sodality of St. Mary’s Church, wearing white sashes and white crosses; they were placed in the Epistle aisle. And then came the Catholic Friends’ Society, and the Conference of St. Vincent de Paul. The church was tastefully draped in mourning, the black festoons in the galleries were relieved with white rosettes, and the mourning on the altar with small white crosses. Over the altar was a large cross, formed of blazing gas-jets; and there was a star of gas-jets [!] in front of the organ. When the clergy, forty-six in number, entered the sanctuary to chant the Solemn Office, the scene was truly grand and impressive.” She then goes to name each of the forty six priests in attendance, treating each one as a celebrity. “The architect of this magnificent structure was [Irish-born] P. C. Keely of Brooklyn, N. Y.,” she continues. He was in fact one of the preeminent architects of Catholic churches in the Northeast in the latter half of the nineteenth century. “The stone work was under the supervision of James Trainor of Boston; the wood work was superintended by James Bulger of Burlington, Vt; and the painting, as we have recently stated, was by Schumacher of Portland, Me. Its cost was over $200,000.” Given that this amount was largely raised by small donations from the commuity, it is quite an amazing sum considering that a laborer made a couple dollars a week. Later, she describes the fundraising campaign to pay for the bells of the church (weighing a total of over 10,000 lbs). The list of donors reads like a directory of Irish residents of Lawrence: John Kiley, Sr., Patrick Moran, John Brennan, Patrick Connors, Joseph Morrissey, James Kilbride, Anne O’Donnell, Mary Anne Quinn, Mary Connolly, Mary Burke, Bridget Bradley, Catherine Cushing, Thomas Regan, Mary Dowd, Mary O’Brien, Mary McCarthy, Rose Walsh, Mary Burns, Sarah McGuohan, Maria O’Sullivan, Annie M. Rafferty, Kate Reilly, Ann Mahon, Mary McGuinness, Rosanna Mulligan, Ellen McCavitt, Hannah Moriarty, Mary J. Sweeney, Ellen Ryan… The list extends for a couple hundred more names, three quarters of them obviously Irish in origin. Far more than half of them are women. Katherine O'Keefe O'Mahoney dedicated her life to promoting Irish pride. I have newspaper clippings of a lecture tour she did in 1911, about Ireland featuring numerous illustrations. She is billed as "a little woman with an enormous voice." Irish Legacy In the Catholic Church By focusing on their religion as a defining institution of being Irish, the Irish came to dominate the Catholic Church in America. “In 1880, the percentages of the clergy who were Irish American was 69 percent in the Archdiocese of Boston…Moreover, in 1886 thirty-five (51%) of the sixty-eight Catholic bishops in America were Irish born or of Irish descent. In 1920, it was still the case that two-thirds of Catholic bishops were Irish American, and in New England, that proportion was three-fourths.” (Source: American Catholics in the Protestant Imagination: Rethinking the Academic Study of Religion, by Michael P. Carroll, 2010) Later, when other Catholic immigrant groups followed - first the French Canadians, then the Poles, Italians, Portuguese, Lithuanians and (a few) Catholic Germans -- they found waiting for them a church that could provide something of a welcome, whereas the Irish basically had to create the Church in New England. Epilogue Since the early 1990s, many of the grand Catholic churches of the original Catholic communities of New England have been closed and often torn down. In Lawrence, this includes the aforementioned Immaculate Conception and St. Lawrence O'Toole, as well as half a dozen other churches. The same pattern was repeated in other urban centers: Lowell, Haverhill, Fall River, Worcester, Boston. I hope this and other blog posts will remind people that these abandoned churches were not just religious institutions, but were part of the physical culture of the immigrant groups who built them. Below: Today's St. Mary's church (Santa Maria de la Asunción)(source: church website) Above: My great grandparents Michael McDonnell and Theresa Doherty McDonnell and some of their children (with spouses), including my grandfather Joseph McDonnell standing next to and behind his mother. Michael owned a meat market and Theresa ran a boarding house across from the Arlington Mill. Michael was born in Lawrence in 1851 on Elm Street, his parents later ran a boardinghouse up Broadway just over the town line in Methuen. My grandfather was born in 1889 at a house on Broadway that straddled the Spicket River, where the little bridge is. Theresa was born in Manchester England where her parents had gone to work in the mills. Her father brought his family over from Manchester England to Lawrence by receiving $600 for fighting in the place of two different men in the Civil War in 1863. Unfortunately he never came back from that war, rather he lived out his days as an invalid in a military hospital in Bangor Maine. I think this picture was taken around 1920.

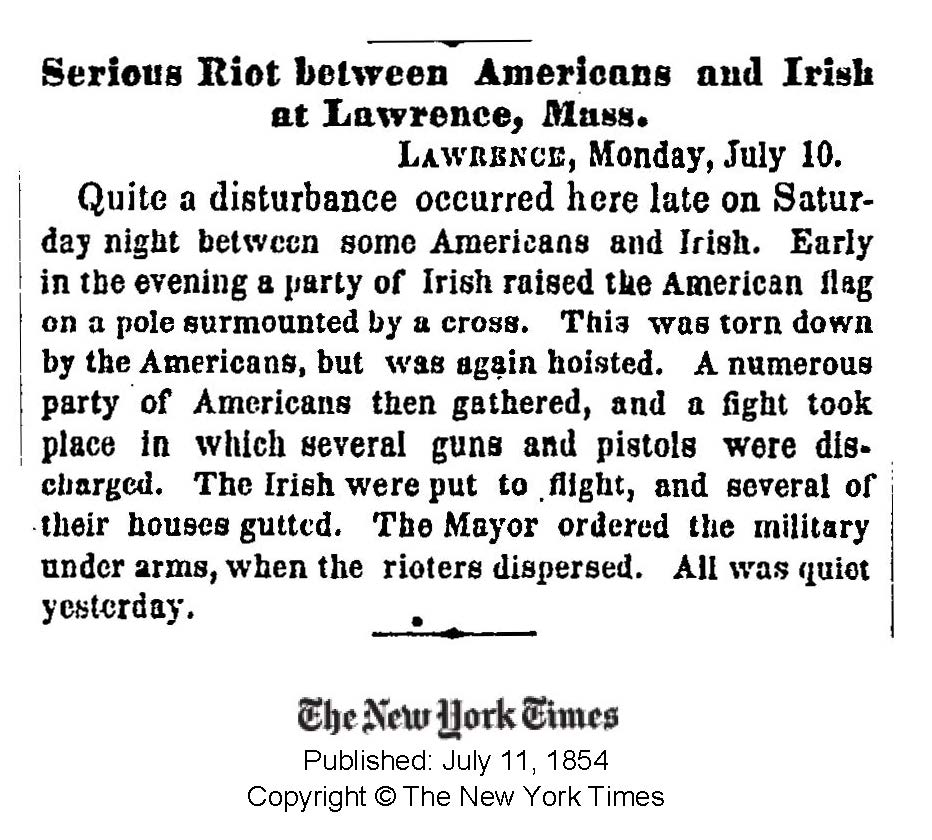

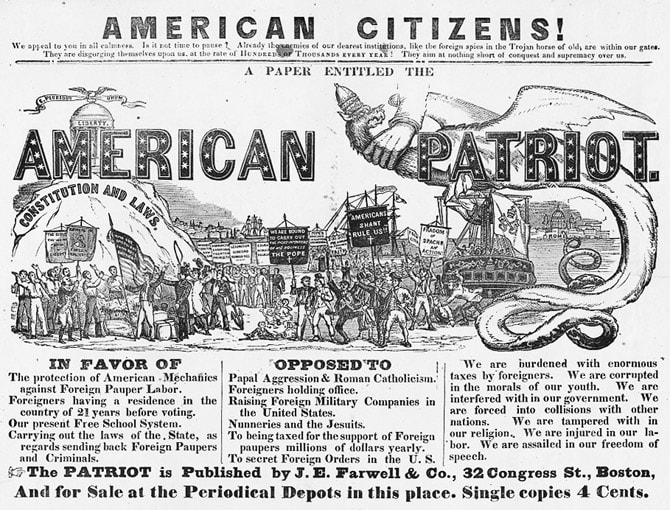

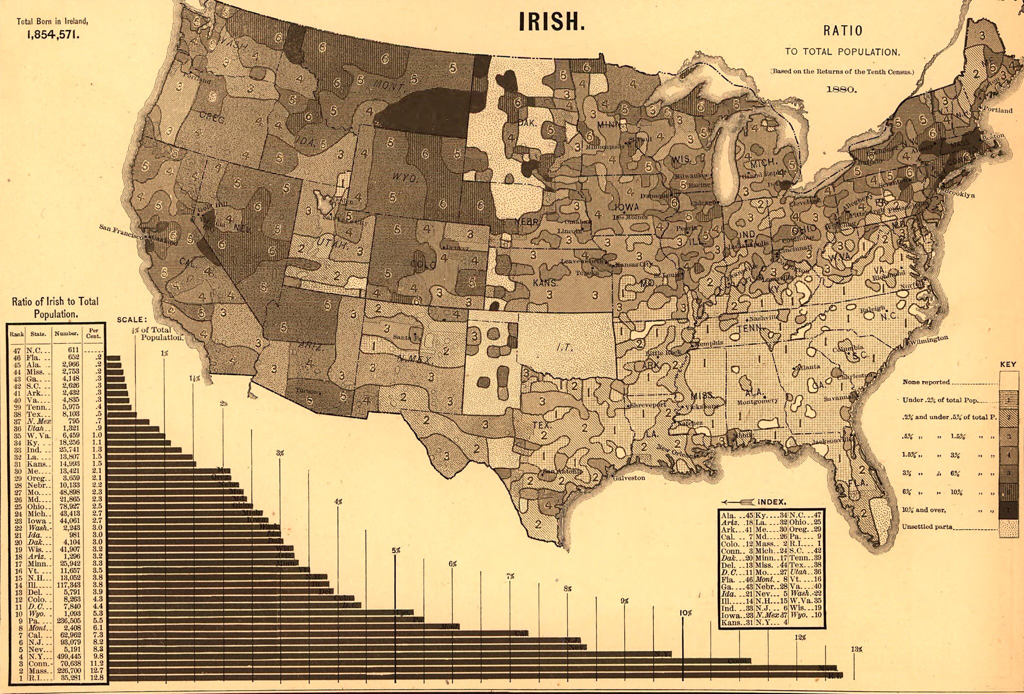

Below: The bridge where my grandfather's birthplace, 541 Broadway, used to be. Photos by me, 2016. In previous blog post, I covered the Lawrence "race riot" of August 1984, which was essentially between a newcomer immigrant group, "the Hispanics", and established natives. Who says history never repeats itself? A century-and-a-quarter earlier, another riot occurred in Lawrence, between a newcomer immigrant group, "the Irish", and established natives. See news coverage above in the New York Times, July 11, 1854. The Lawrence riot of that July 11 was part of a wave of violence aimed at recent Irish immigrants. It swept New England in the summer of 1854, at the height in these parts of the Know-Nothing movement. Know-Nothing politicians stirred crowds with hysterical speeches, about how the Catholic religion was incompatible with American values. "They only answer to religious law and do whatever the Pope and the priests tell them!" "They oppress their women by putting them in convents!" These were the kinds of statements made by the Know-Nothings. It reminds me of hysterical tirades aimed at the supposed incompatibility with American values of the religion of another group of recent arrivals. Just substitute "the commands of the Pope and the priests" with references to Sharia law to see what I mean. The existence of separate religious schools run by and for Catholics particularly incensed many natives, and led to continuous political and court battles through most of the nineteenth century. The "School Question" will be the topic of another blog entry. Think about the context of this anti-Catholic animosity. I'm not defending it, but perhaps it was understandable. Your average New England Yankee had for two centuries been fed a diet of how horrible "Popery" had been, a belief borne out of Protestant experiences with the Counter-Reformation and the religious wars that plagued Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Virtually all New England churchgoers of the time would have shared a staunch belief in the supposed corruption of the Catholic Church, as was finally upended in the Reformation. This was one of the few beliefs that unified the various Protestant denominations that flourished in New England by the 1840s, Congregationalists, Unitarians, Baptists and Methodists being the main ones at this time. Furthermore, very few of these denominations had any liturgy or ritual to speak of in their worship. Also, there were vague collective memories of the French and Indian attacks, led by Jesuit warrior-priests like Father Sebastian Rale coming down from New France (i.e. Quebec) with bands of wild Abenaki Indians to slaughter English villagers. In this context then, imagine how America's first wave of Catholics, the Irish, appeared. Their worship was in a strange language, Latin. This language would have scared Yankee listeners, as it signified the supposed corrupting influences of Rome on true Christianity based solely on original biblical texts, in addition to being completely foreign. Moreover, the Catholic mass (their worship ritual) usually lacked a sermon, full of textual exegesis, which was the mainstay of Congregationalist worship; nor did it have any of the evangelical personalizing of the relationship between the individual believer and Jesus Christ, which, since the Great Awakening in the 1740s, prevailed in the non-establishment Protestant denominations such as the Baptists and later the Methodists. Instead, Catholic worship featured a man in weird robes (the priest) facing an ornate altar, making strange gestures and repeating a bunch of Latin phrases in a prescribed order, while the congregation chanted phrases in Latin in a prescribed order, kneeling, sitting and standing in turn. Imagine how frightening a group of worshipers all kneeling and bowing in unison could be! And then there was the intense scrutiny of convents and nuns, who were assumed to be under oppression and even sexual slavery, with their covered heads and existence behind closed doors. The Ursuline convent in Charlestown, Mass. was burned down by a mob in 1834 on suspicion that women were being held there against their will. And practices like praying the hours (in which devout Catholics visibly pray five times a day at prescribed hours using prescribed prayers based on a calendar), also set off suspicion and animosity, as did its simpler sister ritual, saying the rosary. Below: the cover of the American Patriot, a Boston-based Know-Nothing newspaper, 1854 In addition to the anti-Irish riot in Lawrence, many other New England towns and cities had similar riots that summer: Bath, Maine (in which a Catholic church was burned down); Ellsworth, Maine (in which a priest was tarred and feathered); Chelsea, Mass. (in which a Catholic church was attacked); Dorchester, Mass. (in which a Catholic church was destroyed by dynamite); and Norwalk, Conn. (in which St. Mary's catholic church was set on fire and its steeple sawed off), among other places. In Manchester, New Hampshire on July 4, 1854 a skirmish between some Irish youth and some "natives" over a bonfire that the former group wanted to light escalated into significant violence. The local newspaper account stated that a "large number of men, armed with clubs and other destructive implements, about day-break, commenced an assault upon all the Irish houses in that neighborhood. Some ten or fifteen were pretty thoroughly dismantled—the doors and windows of many of them being completely stove in. The rioters next proceeded to the Catholic Church—just re-built at great cost, and probably the handsomest in the State—and continued their fiendish work. …" (Manchester Union Democrat, July 5, 1854). These anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic sentiments swept the Know-Nothing American Party into power in the Massachusetts state legislature in 1854. "While much of the American Party’s platform was socially progressive, its highest priority was reducing the influence of Irish Catholic immigrants, and the party became the home of wildly divergent social movements attempting to organize under one political umbrella....The Massachusetts Know Nothing legislature appointed a committee to investigate sexual immorality in Catholic convents, but it was quickly disbanded when a committee member was discovered using state funds to pay for a prostitute." (Historic Ipswich blog entry on the Know Nothings) By 1858, however, the new party was a spent force, and was defeated in almost all local and state elections. It also did little to thwart the continued growth of the Catholic Church in Massachusetts and New England, as Irish immigrants continued to pour in while their church organized itself under Irish leadership. Later, Irish domination of the Church hierarchy led to resentment by other, later Catholic immigrant groups, such as Italians and French Canadians - that topic will be covered in a blog entry about "National Parishes". Map showing concentration of Irish-born in 1880. Note Massachusetts. My own theory is that the Catholic Church of the Irish variety flourished in New England despite considerable native animosity in from the 1830s through the Civil War, because of a long history in Ireland of persevering under conditions of adversity and oppression.

Above: My great grandparents Michael McDonnell and Theresa (Doherty) McDonnell, circa 1920, Lawrence, Mass., surrounded by a number of their children and spouses. My grandfather is behind and to the left of his mother in the back. You asked me about my family history. Or I presume you did, otherwise you would not have showed up here. I grew up in a unique place. I grew up among ghosts. They were left by previous generations through their stories. When I was little, my father would drive around my hometown of Lawrence, Mass. and tell the story on every corner about something that happened there to him, or to his father or his mother. The same was true for my mother. They had each left Lawrence for the big wide world, my father to the Marine Corps, U. Chicago and beatnik travels and my mother to a schoolteacher job on Long Island and cruises on the Queen Mary to Europe, but each had come back. They had returned to a town that barely existed in its prior form, yet which carried the narrative of all prior generations. The collective story of Lawrence as told through my ancestors is one of migrants from far or near being caught the industrial town and staying there for generations. This fate is not as grim as it seems; the industrial town was the source of all forms of economic activity. There were shops, there was commerce and there was some higher education in addition to the factories. On my mother's side, the story begins with the Irish potato famine. Her forebears, Irish all of them (and Catholic) were usually illiterate and had almost to a person arrived in the late 1840s. Interestingly, from the earliest generations there was a streak of the entrepreneurial. Her great grandfather John McDonnell and his wife ran a boarding house on Broadway in Methuen just over the town line with Lawrence. It is recorded in the census. This line of business was again pursued by her father's parents with a boardinghouse on Broadway across from the massive Arlington Mills complex, employer of 4,000 workers at its heyday around 1920. Said paternal grandfather also ran a butcher business, and after that he was an undertaker. On my mother's mother's side, too, there was a streak of enterprise with some focus on hospitality. Although the immigrant progenitor, one Jerry Driscoll, was but a laborer, he sold his services to the Union Army for $300 in 1863 and then used the proceeds to buy some land, including the land under the house into which my mother was born. Jerry's extensive lands in North Andover became the seed capital for his three sons: a builder, a dairy farmer and my mothers grandfather, a saloon keeper. My mother's parents, hoteliers and smalltime real estate developers of the New Hampshire seacoast, were therefore a match well-destined. The story of my mother's father is worth mentioning, since he was not more than a boy when he entered the mills in Lawrence around 1903 after leaving the eighth grade. However it must've been an arrangement, because instead of working a loom, he worked as an apprentice carpenter and machinist -- a job normally reserved for Protestant citizens. Family legend has it that he was mistaken for a Scotsman by confusion over his surname: McDonnell instead of McDonald, allowing him to get a better job. Or maybe this was just the cover arranged by a family friend. In any case, as a result of his training in the mills as a carpenter and machinist, by age 30 he had amassed enough fortune to purchase and build the first motel in New Hampshire, the Sunrise Motor Court in Hmapton Beach, a burgeoning local vacation destination for millworkers made possible by the advent of the motorcar. Joseph's eleven brothers and sisters also led equally fruitful and successful lives. As the stereotypically lazy third generation of Americans, they nevertheless assimilated and got along very well in the larger economy, becoming such things as a potato chip dealer and manufacturer; a soda manufacturer and distributor; a college-educated school teacher; and car salesman. In short, they were the type of generally successful and solid citizens. 1850s grave of Irish infants in one family, from the old section of the Immaculate Conception Cemetery in Lawrence, Mass. Photo by the author.

Jewish Lawrence observed: My grandfather's retirement in 1949 to the top of Tower Hill in Lawrence12/9/2017 Above: My grandparents Mary (Driscoll) McDonnell and Joseph McDonnell at my mother's college graduation, 1960

I'm interested in the history of my grandfather's relationship to his Jewish neighbors. Specifically I wonder how he ended up building his retirement home in 1949 in the then-predominantly Jewish neighborhood of Tower Hill in Lawrence Massachusetts, moving from his prior home in the Irish section of South Lawrence, along Kingston Street by St. Patrick's Church If I consider this move, along with other indicators – for example, that every winter he and his wife would travel to Fort Lauderdale Florida for their annual vacation, or that he was a smalltime real estate developer, or that he may have had a tendency to obfuscate his Irish Catholic background (he told mill overseers his surname was McDonald, which was Scottish, and which allowed him a better job) – the pieces of a puzzle perhaps begin to emerge. Consider Lawrence in the 1940s. When he began building his house in 1949 at the age of 60, the city was still regional center, although on a terminal decline. He had worked for four decades as proprietor of hotels and rooming houses and was entering retirement with his wife. Summers were spent running the properties at a New Hampshire resort for the workers, Hampton Beach, and winters were spent in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Tower Hill in Lawrence, the location of his new home, had in the postwar years become the preeminent Jewish neighborhood of greater Lawrence. This period, especially the early 1950s, was marked by the construction of two synagogues on the upper part of Lowell Street and a Jewish community center (JCC) within 100 yards of the site of his new house. (One of them, Temple Emanuel, moved to Andover in 1979 and its buildings became the Bruce School annex magnet school mentioned in my blog post on the 1984 Lawrence riot.) The local public school, the Bruce school, which I attended for nine years starting in 1976, apparently allowed days off for Jewish holidays and was at one point in the early 1960s over half Jewish. Question: did my grandfather choose the neighborhood because he perceived it as an appropriate home for a successful businessman, much like the other residents of this neighborhood; or did he have specific personal links to some of the Jewish residents? And, tangentially, why did he winter in Fort Lauderdale? He had been going there for years, and in 1926 purchased a significant parcel of land which they later sold in the 1950s. I'm not sure it's possible to gather any more information. From talking to my mother, I get the impression that his friends were mostly related to his wife, my grandmother Mary Driscoll, a sociable and gregarious woman who had a penchant for Cadillacs and fur coats. Yet I can also imagine a separate sphere of business colleagues, untethered from being "couples friends" – men who developed apartment buildings and commercial real estate, or who had businesses focused on hospitality - who might have influenced his choice of where to retire. The final puzzle piece is his choice of developing property in Hampton Beach, N.H. This town was restricted, and covenants running with the land routinely prohibited sales of property to Jews, unlike the practices in the neighboring seaside resort areas of Salisbury, Mass. For this reason alone, I have concluded that any decisions of my grandfather to retire to Tower Hill in Lawrence, or to winter in Fort Lauderdale, had nothing to do with whether they were Jewish areas. Nevertheless, I will cotinue to investigate this topic. ULDATE MARCH 7, 2018: I have since learned that, whereas Miami Beach was considered fairly Jewish, Fort Lauderdale was “waspy”. Thiis plus the restricted nature of Hampton Beach probably kills my thesis that my grandfather moved to Tower Hill because he had Jewish business connections. The property that became 78 (far left house) and 80 Kingston Street in South Lawrence was bought by my great grandfather Jeremiah Driscoll in 1867 for $168, when the land was parceled but not yet graded for streets. Jeremiah previously lived in the Irish shantytown of which this site was a part. Eleven relatives either were born or died in these houses over the years. They were sold in 1948 by my grandmother Mary Driscoll McDonnell, who was born at 80 Kingston Street in 1900.

Below is an excerpt from the Lawrence city directory in 1864. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed