|

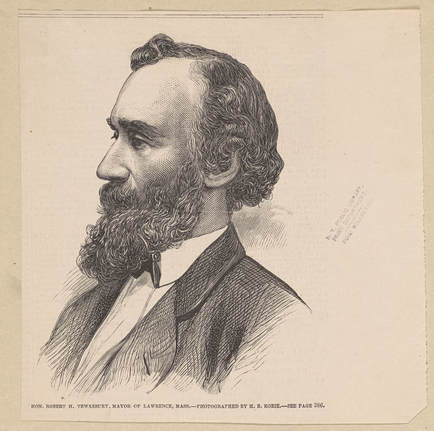

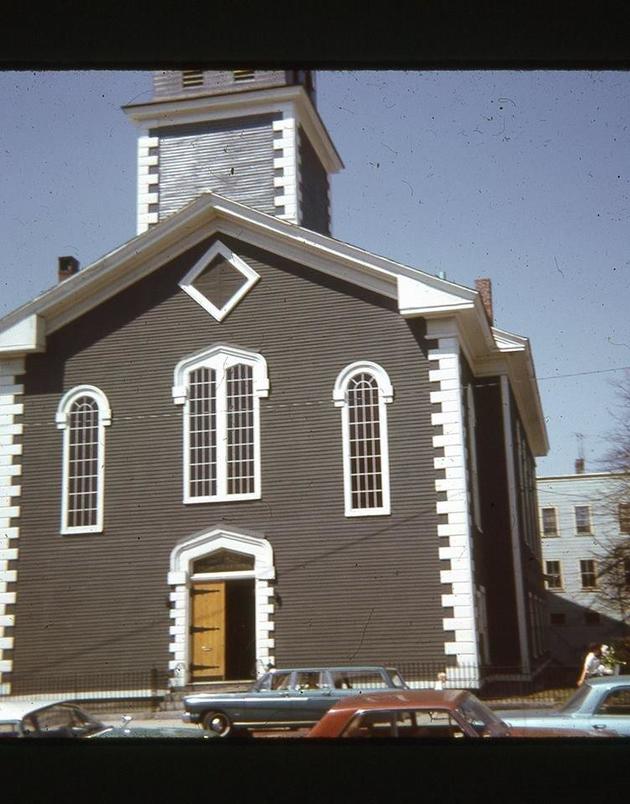

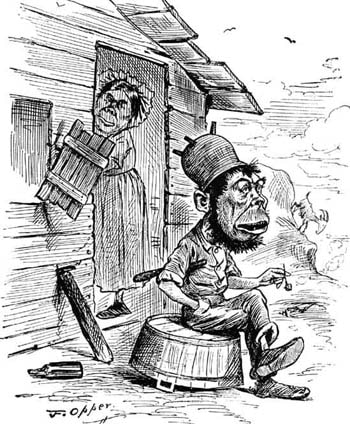

If you’re over forty, you probably remember bumper stickers like this all over Massachusetts: Among persons of Irish descent, support for the Irish Republican Army (IRA) was widespread, even if it was superficial. Somehow it was okay to like Princess Diana and Irish republicans… The IRA story was easy to understand. The British army was an occupying force. IRA men were freedom fighters, naturally fighting for a unified Ireland. British empire, bad. Freedom fighter, good. It’s all very romantic. Almost nobody from the area knows the story of the “other side”, the so-called Ulster Orangemen, who also made the region of Ulster their home. They were fighting for minority rights just as much as the IRA. Below: Logo of the Ulster Defence Association, paramilitary group The history of the Orangemen in a nutshell Ireland was ruled by the English crown starting in the 1500s. In the early 1600s, Scotland was technically still a separate kingdom. The English king had a problem. What to do with all those pesky Scots who lived on his side of the English-Scottish border? They kept trying to rise up against him. Solution: deport them to Ireland. These “Scots-Irish” (Americans like to say Scotch-Irish) were given land and rights in the province of Ulster, which was called a Plantation. They were supposed to raise sheep and pursue other productive ventures. Some of them soon left Ulster and settled the hillbilly regions of the United States. That’s another story. The ones who remained in Ulster had a tenuous relationship with the English powers. They refused to kowtow to the Anglicans who ran everything. Instead, they followed a very Calvinistic form of Presbyterianism. Although they had more rights and wealth than the Catholic population, they were an often-second-class minority within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Below: Political Cartoon from 1913 Regarding Ireland "Home Rule" When Ireland began to break away from Great Britain, the Ulster Scots leveraged their close-knit status as a political force. They won the separation of most but not all of the Ulster province from independent Ireland. The section in which they were a majority remained with Great Britain. The Ulster Scots saw themselves as a beleaguered minority of Ireland proudly clinging to their traditions. The British crown was now their protector, hence their extreme loyalism. The Orangemen One of the big traditions among Ulstermen is a commemoration of the Battle of the Boyne (July 12, 1690). In this battle, Protestant William of Orange, who rule as co-regent with his wife Mary II (hence the reign of William & Mary), defeated the deposed King James II, thus thwarting James’ failed bid to restore Catholicism to Great Britain. To commemorate this victory, Orangemen hold marches. During the “Troubles” of Northern Ireland, from 1969-1998, often these marches were designed to provoke their Catholic rivals, just as republican (meaning pro-Republic of Ireland) countermarches were designed to provoke Ulster communities. Technically, the Orangemen are a fraternal organization, comprised mainly but not exclusively of Ulster Scots (some are descended from English settlers of Ulster). It was technically founded as a brotherhood for all Protestants, in 1795 in County Armagh in Ulster. Below: Typical procession of Orangemen in Northern Ireland, July 12, 2016. PHOTOGRAPH BY Michelle McCarron. What does any of this have to do with the Merrimack Valley?? On July 12, 1875, the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne, a group of self-styled Orangemen held a picnic on the banks of the Merrimack River in Methuen. When they returned to Lawrence by way of steamer to Water Street, they were met a mob of 200 Irish Catholics. A riot erupted, and police fired at the mob. Here is the coverage from the New York Daily Herald: “Lawrence, Mass. – A serious riot occurred in this city to-night, resulting from an outbreak made by a mob upon the members of a lodge of Orangemen returning from celebrating the ‘Battle of the Boyne’ at a picnic at Laurel Grove, four miles up the Merrimac River. Orangemen from Lowell, Woburn and other towns participated at the picnic, which passed off quietly, and no trouble was anticipated when they dispersed for their homes, though some threats had been made in the morning and some of the men carried firearms in consequence. MOBBING THE LADIES About a dozen Orangemen, with ladies and children, disembarked at eight P.M., at the steamer landing on Water street, and started to walk up town. A crowd of several hundred Irish were at the landing and followed them, shouting and jeering. When they arrived in front of the Pacific Mills, the crowd commenced throwing stones, one of the ladies being struck three times and badly hurt. All the party were more or less injured by missiles thrown at them during their half mile walk to the police station, whither they went for protection. Four of the men had on regalia, which particularly incensed the mob. One of the men was severely hurt about the head and had his sash torn from him THE MAYOR JEERED AT On their arrival at the police station word was sent to the Mayor [ed: Robert H. Tewksbury], who soon arrived at the scene and undertook to disperse the mob of men and boys, but without avail; the cries and jeers of the mob drowned his voice. The Mayor, with a squad of police [editorial note: who were probably mostly Irish Catholic!], then started to take the party through the crowd to their homes. SHOWERS OF STONES Essex Street, through which they had to pass, was at this time filled for half a mile with the mob. Showers of stones, bricks and other missiles was [sic] hurled at the party as soon as it appeared upon the street. With the exception of the Mayor every one of the party was hurt. Policeman Gummel was knocked down and badly hurt. James Sprinlow, who was endeavoring to protect his brother’s wife, was knocked down, received a terrible wound in the head from a brick. At the corner of Union and Spring streets the mob made a furious onslaught of the party, when nearly all the police and Orangemen were knocked down. The latter then, in self-defense, drew their revolvers and began firing on them on the mob, who were shouting ‘Kill the damned Orangemen.” THE WOUNDED The firing quickly dispersed the mob, who scattered in all directions. It is impossible to learn the accurate result of the shooting. So far as known no one was killed. Two men, one woman and a boy twelve years old, were wounded; none seriously. Of the Orangemen twelve were wounded by stones and bricks, some of them quite seriously, and four policemen were more or less hurt. COURAGE OF THE MAYOR The riot lasted two hours and a half, and extended over a route of a mile through the most thickly portion of the city. It is the most serious affair of the kind that has occurred since 1852 [sic? Is this right? I thought the anti-Irish riot was in 1854], and is condemned on every hand as most unprovoked. The courage of the Mayor undoubtedly saved many lives.” Below: Robert Haskell Tewksbury (1833-1910), Mayor of Lawrence in 1875 Mary O’Keefe, whom I have written about, condemned the riot. She specifically cited the efforts by Irish Catholic clergy to distance themselves from the events. “And now we come to an event which we are doubtful about mentioning in a sketch of Catholicity in Lawrence for testing as we do, that Catholicity had no share in it. We refer to the ‘Orange riot’ which took place on the 12th of July, 1875, the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne, and was, by an accident, very largely advertised all over the country, and, of course, ridiculously exaggerated. However, lest we should be understood as acknowledging, by our silence, the truth of these reports, we here insert a card signed by the Catholic clergy of Lawrence, and published, at the time, in all the local papers. It expresses not only their sentiments, but those of all others in the city deserving the name of Catholics. “We, the undersigned, Roman Catholic clergymen of Lawrence, desire to publicly make known our condemnation of the riotous proceedings of last Monday evening. We do not consider as Catholics, in the proper meaning of the term, those who participated in the disturbance of the public peace, and who, by their shameful conduct, sullied the fair fame of our city. We teach our people good will towards all men, and we strive, by precept and example, to impress upon them the importance of faithfully observing the laws. We trust that the few ruflians who, under the name of Catholicism versus Orangeism, have created such bad feeling and given rise to so much trouble, may be made to feel the enormity of their crime. – SIGNED W. H. Fitzpatrick, Pastor of the Immaculate Conception Church; J. H. Mulcahy, Asst. Pastor of the Immaculate Conception Church; Jno. P. Gilmore, D. D. Regan, J. A. Marsden, O. S. A., Pastors of St. Mary’s Analysis and Questions What I would like to know: were these marchers really Orangemen, meaning they were really of Ulster descent? I have never heard of any Scots-Irish living in Greater Lawrence. I asked the Lawrence History Center, who have a redoubtable collection of materials related to dozens of different immigrant groups to the area. They have nothing on Scots-Irish, Ulstermen, Orangemen or anything similar. (There was however a large Scot-Irish settlement in Londonderry, New Hampshire - however, this town is probably too far away to have been the source of these marching "Orangemen".) I can’t help but think the march was of anti-Catholic types, of which there were still many (soon I hope to write about the Catholic school controversy of 1888 of Haverhill). But more research is needed. If anyone’s ancestor was a member of the Grey Presbyterian church in Lawrence, it would be great if you could contact me about the origins of your ancestors. Below: First Presbyterian Church (The Grey Church), 315 Haverhill Street(?), Lawrence, Mass.

0 Comments

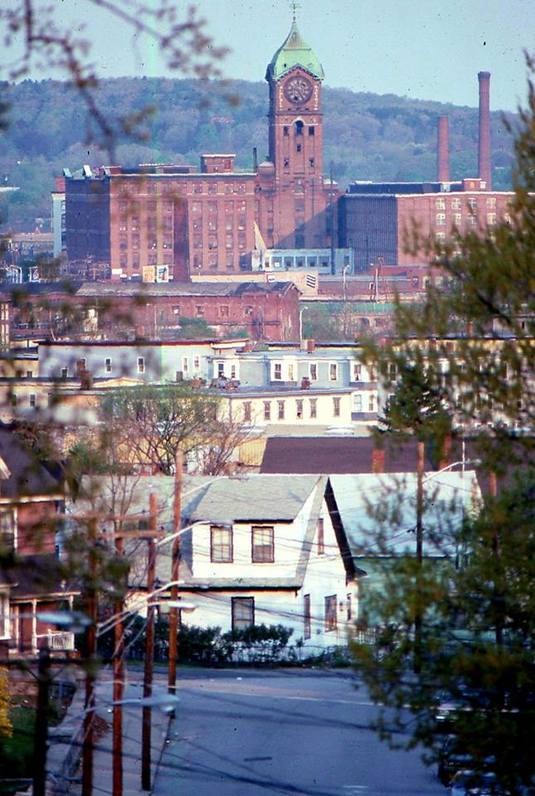

The Ayer Mill Clock Tower hovers above Lawrence, mid 1980s. Photo by Butch Fontaine.

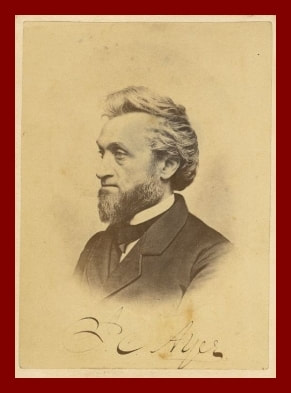

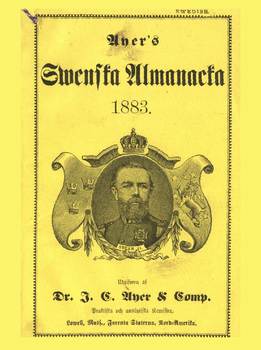

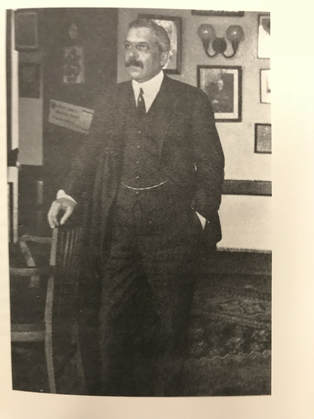

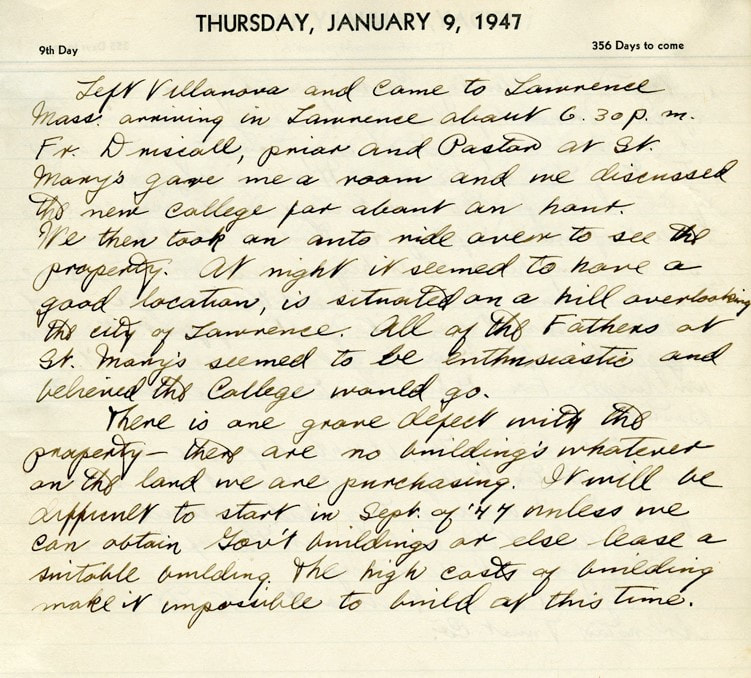

The Ayer Mill Clock Tower as a landmark There aren’t many landmarks left for a Lawrencian to point to. The beautiful post office? Demolished. The grand old police station? Demolished. “Theater Row” where many mill workers and their children watched the latest Hollywood talkies? Gone. Department store Sutherlands and the other large retail establishments of Essex Street? Gone. Also gone are many nice churches and schools, and even whole neighborhoods demolished for “urban renewal”. Most of the surviving Lawrence landmarks are industrial: the Great Stone Dam that made the whole place possible; and the mills lining the river and canals – the Pacific, the Wood, the Everett, etc. About half of the old mill buildings have been demolished. By far the most prominent landmark left in Lawrence is the clock tower of the Ayer Mill, now a New Balance factory. The tower rises 276 feet and is visible from many parts of the city, as well as from Interstate 495 passing by on the elevated roadway. It is the biggest mill clock tower in the world. As we all know, its clock face is only six inches smaller than the one on Big Ben. After decades of neglect the clocktower was restored in 1991 and has been maintained ever since. Below: Video of New Balance factory in Lawrence, Mass. This blog post tells the fascinating life story of its namesake, Frederick Ayer, peddler of patent medicines and almanacs who diversified into textiles. After you read it, maybe you’ll start calling the Ayer Mill clock tower “Big Fred”. Frederick’s background Practically every person in this country with the last name of Ayer – including my great grandmother Mildred Ayer – is descended from the original American Ayer [or Ayre or Ayres], named John. He was born in 1582 in Salisbury England and was a founder of Haverhill, where he died in 1657. John Ayer was Frederick Ayer’s fourth great grandfather, making Frederick a Haverhillite of sorts (and my sixth cousin five times removed). However, three generations earlier his family had moved from Haverhill to the coast of Connecticut. Frederick was born in Ledyard Connecticut, near New London, in 1822. Below: Frederick Ayer late in life. Source: Wikipedia His Brother James Cook Ayer and Ayer’s Patent Medicines For the early part of his life, Frederick followed in the shadow of his older brother, “Dr.” James Cook Ayer, born 1819. James studied medicine, apparently in Philadelphia, and may or may not have become a proper doctor. He did however become an extremely successful proprietor of patent medicines. James started practicing as a pharmacist in Lowell in 1841 at age twenty-three. His uncle lent him the money to buy his original pharmacy in Lowell. He settled there because his mother, a Cook, was from the Lowell area. He was a graduate of Westford Academy in neighboring Westford, Mass. Below: "Dr." James Cook Ayer, from his 1874 congressional campaign While a pharmacist James began developing cures for his customers’ ailments, and soon founded J.C. Ayer & Company. His five major products were Cherry Pectoral (“cure-all”), Cathartic Pills (laxative), Sarsaparilla (cure for syphilis and other “blood disorders”), Ague Cure (anti-malaria), and Hair Vigor (against thinning hair). Cherry Pectoral was by far his most popular and profitable product. Its popularity was possibly aided by three grams of opium in every bottle. In 1859, the company built a facility at 165 Market Street, Lowell, which they later expanded. By 1865, Ayer employed 150 people. In one year the factory processed 325,000 pounds of drugs, 220,000 gallons of spirits and 400,000 pounds of sugar. Below: Ayer's Cathartic Pills. Source: Cliff Hoyt website (http://cliffhoyt.com/jcayer.htm) Ayer’s Almanac James distinguished himself from other quacks – um, I mean doctors – by means of extensive advertising. In 1851, he hit upon the idea of providing a free almanac to all his customers. Almanacs were already essential household items, offering a range of helpful information for the current year – from public holidays to suggested planting times to town directories to historical summaries. However, James also peppered his almanac with advertisements for his products. Print production of Ayer’s Almanac is estimated to have exceeded 16,000,000 and was possibly as high as 25,000,000. The J.C. Ayer Company’s modest slogan for its publication was ‘Second only to the bible in circulation.' The almanac was eventually published in twenty-one different languages, reflecting the burgeoning immigrant population of the last decades of the nineteenth century. Below: Examples of foreign language copies of Ayer's Almanac (Source: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/almanac/heyday.html) James looked for a marketing opportunity wherever he could find it. For example, during the Civil War when Congress allowed postage stamps to become legal tender due to a shortage of currency, James encased stamps in miniature advertisements to protect them from wear and tear but also market his brand (source: www.cliffhoyt.com/encased_postage.htm). Below: Encased postage stamps bearing J.C. Ayer insignia (Source: Cliff Hoyt website http://cliffhoyt.com/encased_postage.htm)

Above: Advertisement for Ayer's Sarsparilla. Source: NIH website

Transition of The Medicine Business to Frederick; James’ Business and Political Pursuits; His Untimely Death In 1855, James offered his brother Frederick a partnership, and ceded day-to-day operations to his younger sibling. He started to become a man of wealth and leisure, traveling on extensive tours. In 1865, he purchased a statute on a trip to Germany and presented to the City of Lowell. This “Winged Victory” statue still stands today in Monument Square in front of Lowell City Hall. Below: Victory Statue, Monument Square, Lowell (Source: Wikipedia) By the 1850s, he was looking for investments for his enormous profits. However, he seems to have been the “dumb money” that came in late – in 1857, he lost $2 million dollars when the Bay State mills in newly founded Lawrence went bankrupt. That was an enormous sum of money in those days. Later, in his book Some of the Uses and Abuses in the Management of Our Manufacturing Corporations, he complained of the ways in which shareholders like him were denied a voice because entrenched management controlled the governance apparatus of corporations. Basically, he said, the insiders rigged shareholder elections. These days, someone like James C. Ayer is called an activist shareholder. In the book James launched an attack on the firm of A. & A. Lawrence, the powerful firm founded by brothers Abbot and Amos Lawrence, consummate Boston Brahmins and benefactors of great cultural institutions. (Lawrence, Mass. is named after Abbot Lawrence.) I take this as an indication that the Ayers were outsiders, not connected to the commercial elite of Boston, such as the Lawrences, with their ties to Harvard and Unitarianism (you know, “Cabots talking to Lowells and Lowells talking to God” and all that). This observation helps explain Frederick Ayer’s very unusual decision, in 1886, to allow the swarthy Portuguese immigrant’s son, William Wood (a.k.a. Guilherme Madeira), to run his textile empire and marry his daughter. More on that below.

Ayer, Massachusetts (formerly a section of Groton) was set off and named after James Ayer in 1871 when he paid for the new town’s city hall. He had dreams of becoming an important public figure. In 1874, he ran for Congress and was heavily defeated. He was so unpopular, the citizens of Ayer even burned him in effigy. This was apparently too much for his ego to handle. He went mad, spending a number of months at a private insane asylum in New Jersey. James died in 1878, leaving his brother Frederick to run the family business empire for another forty years until his death in 1918.

Below: The Town Seal of Ayer, Massachusetts, named after James Cook Ayer Frederick Ayer Takes Over In 1878, Frederick was fifty nine years old and a millionaire many times over thanks to the patent medicine business. However, by this time he had embarked on his second act: textile magnate. After a number of setbacks – and the loss of stupendous amounts of money as his family’s mills in Lawrence kept going bankrupt – he managed to get a handle on matters by hiring William Wood of Fall River to run the businesses. The relationship began in 1886 when Ayer met Wood while the latter was selling shares to a new mill he wanted to build in Fall River. Instead of investing in Wood’s mill, he hired Wood to help run Ayer’s mill in Lawrence, the Washington Mill. One thing led to another, and within a few years Wood was making $25,000 a year (up from his original pay of $204 a year) and he had married Frederick Ayer’s daughter. Below: Frederick's Son-in-Law, William Madison Wood, 1914 (Source: McClure's Magazine) As William Wood’s biographer wrote of the 1888 marriage between William Wood, age 30, and Ellen Wheaton Ayer, age 29:

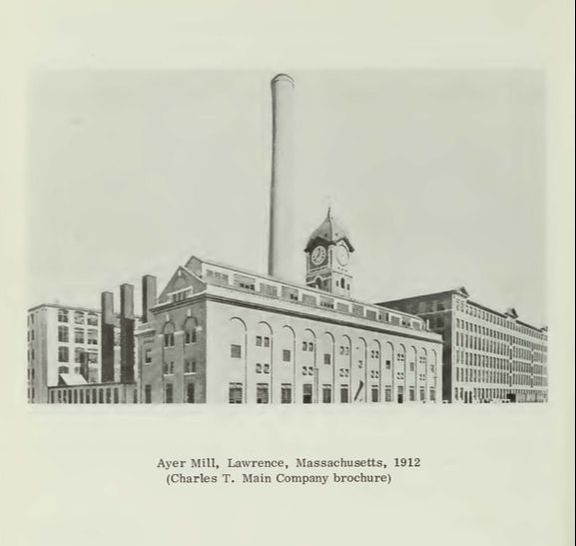

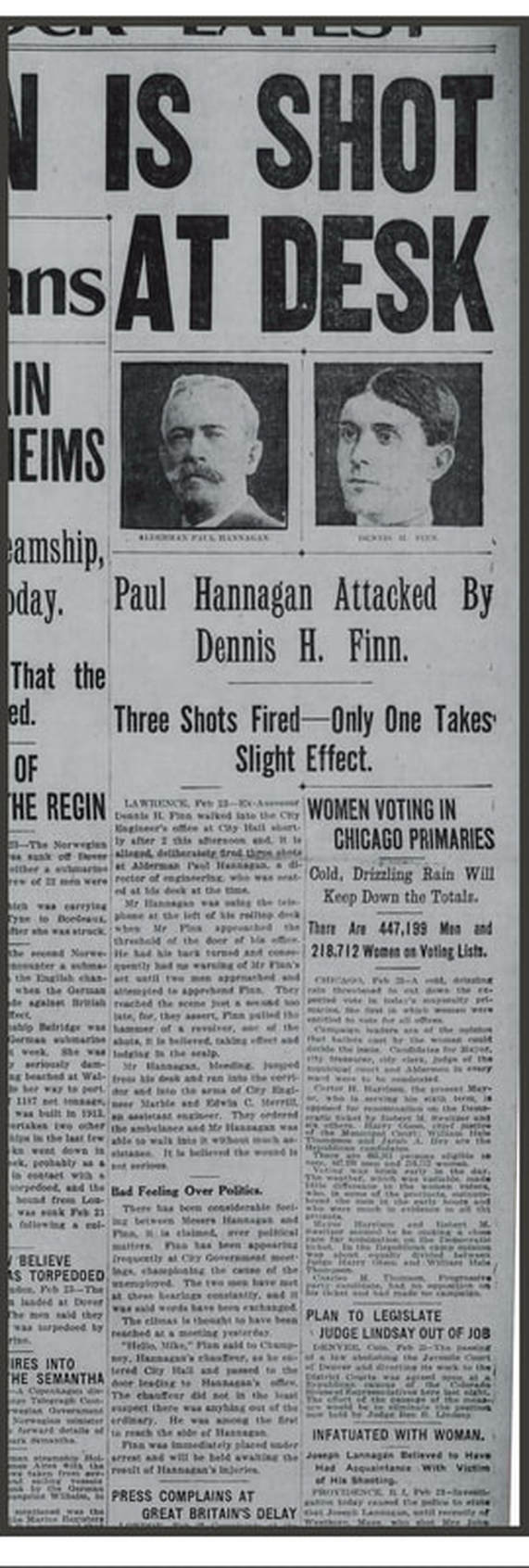

in addition to his involvement in patent medicines and textiles, Frederick Ayer was a founding director of the New England Telephone and Telegraph Company, serving in that role from 1877 to 1896. He was also a founding director of the Lowell & Andover Railroad, a subsidiary line of the Boston & Maine, serving from 1873 to the time of his death. (Source: his New York Times obituary, March 15, 1918.) Below: The Frederick Ayer Mansion, 357 Pawtucket Street, downtown Lowell (Wikipedia) Above: Brochure for the Ayer Mansion on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston Frederick Ayer was President of the American Woolen Company until June 1905, when he retired at the ripe old age of 83. Keep in mind that Ayer was still having children (with his second wife after the first one died) as late as 1890, when he was sixty eight! Frederick Ayer lived to be 95, passing away in 1918 in Thomasville, Georgia, known as “Yankee’s Paradise” for the number of northern industrialists who had winter homes there. One of James’s daughters married George Patton, the famous American commander in World War I. In 1909, William Wood honored his father-in-law by naming his most architecturally prominent mill after him. Below: Illustration of the original Ayer Mill complex from a company brochure, 1912 The Ayer Mill The following is a description of the Ayer Mill in a wonderful study of the architectural heritage of the lower Merrimack Valley by Peter Molloy (published 1978 by the sadly now defunct Merrimack Valley Textile Museum): “The Ayer Mills were designed by Charles T. Main Architects and built for the American Woolen Company as that firm's third worsted mill in the city of Lawrence. The mill was named for Frederick Ayer, a Lowell patent medicine manufacturer and the father-in-law of William Wood, the President of the American Woolen Co. The Ayer Mill manufactured worsted suitings and every operation in worsted manufacture was accomplished within its two mill buildings and dye house. An underground tunnel connected the Ayer to the Wood Mill, which was situated within 200 feet of the Ayer. During the 1950s the American Woolen Company ceased operations, and the Ayer Mill was tenanted to a number of small concerns. The dyehouse and boiler-turbine house were destroyed to create a parking lot. The boiler-turbine house contained eight 600 HP boilers and two 2. 5 MW turbo-generators. The dyehouse was 2 stories, brick, 90' x 126'. Of the two remaining mill buildings No. 1 is brick, 6 stories in height, 123' x 595'; No. 2 is 7 stories, brick, 123'x329'. The 2 mills are connected at the east end by an 8 story building, 40'x81', which contains water closets and stairways. Another building, 40'x81', connects the west ends of mills 1 and 2. This building was used as a stair and elevator tower. Above the roof level of this building rises a 40' x40' brick tower, the weather vane of which is 267' above street level. In the tower was a 20,000 gallon water cistern, a bell, and a clock with 4 illuminated dials each 22' 6" in diameter. The buildings were decorated with elaborate facades in a neo-Georgian style, with pediments, granite coursings, and Palladian windows. The buildings are among the most highly styled 20th century mills in the United States. In 1910, the mill's first year of operation, it contained 75 worsted cards, 80 combs, 45,000 spindles, and 320 broadlooms. It employed over 1,000 workers. Although situated near the Essex Company's South Canal, the Ayer did not utilize water turbines, but it did use water from the canal for process and boiler water.” Below: Frederick Ayer grave, Lowell, Mass. (Source: Find A Grave)(Note the famous "Ayer Lion" in the Lowell Cemetery is James's grave) The Boston Globe reported on February 23, 1915, ex city assessor Dennis H. Finn fired three shots at Alderman Paul Hannigan, grazing his head. The reason given: "Bad Feeling Over Politics". Here is the article. Scroll to the bottom for a higher resolution pdf of the article, which is more legible.

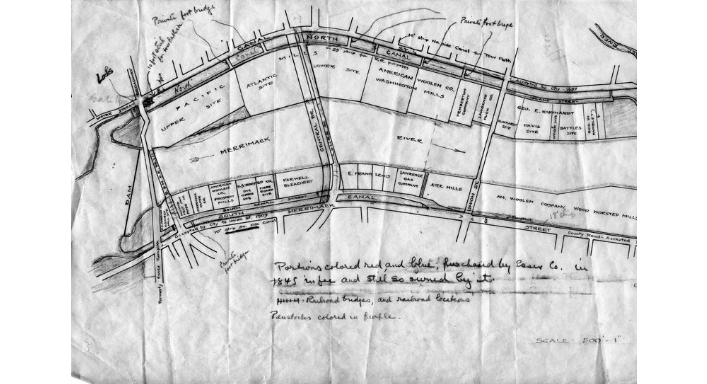

Above: Katherine O'Keefe O’Mahoney, born Ireland 1855, died Lawrence, Mass. 1918 (Source: Lawrence, Massachusetts by Ken Skulski, 1995) The Backstory Before there was Lawrence, there was ye olde New England: clapboard farmhouses, village greens, slow-moving farmers who mended their stone walls and carted their produce to market. This is how things were in 1845, the year Lawrence was founded as a town. Things in 1845 really weren’t all that different from 1645, two hundred years earlier, when the area was first settled by English Puritans in the towns of Andover and Haverhill. The ancient towns were later carved into the towns that we know today – Methuen, Salem N.H. (both formerly part of Haverhill), North Andover (the original part of Andover)…and Lawrence. Sure, the railroad had been introduced a decade earlier, and the Puritans had mellowed somewhat. People were no longer executed for witchcraft or whipped for heresy. But the culture was basically the same as it had been for generations. The original Puritan settlers had come forth and multiplied, cleared the land, built meetinghouses. Some of them went off to sea, chasing whale oil or Far-East silks and spices; or enterprisingly built waterwheels to grind their neighbors’ grain. Some of the local militia boys had gone off to the Battle of Bunker Hill and other early encounters of the Revolution. Basically, however, people farmed, traded, read their King James Bibles, attended meetinghouse, lived and died. Things were homogeneous and consistent, generation after generation. Below: Typical New England farm of the early 19th Century, similar to Bodwell's Farm in what became Lawrence (Source: New England Historical Society) Then, in the second half of the 1840s, two things happened: (1) industrialization and (2) a refugee crisis. Here Come the Factories The fast-moving tributaries of the Merrimack River had always powered waterwheels – little mills that were used to grind grain, saw logs into boards, or run a few looms to supplement the homespun cloth. However, in the 1840s, the mills being planned were different: they would now be on a grand scale. The immense new wealth of the spice trade and whaling was chasing new investments, and could finance endeavors on a previously unimaginable scale. The industrial revolution was underway in Britain and provided the technology. The planned textile city of Lowell was the first example, as we all know, but bigger and bigger factories could be planned. So a group of rich Boston merchant pooled their capital to form the Essex Company. In 1845 this company started to build Lawrence in a backcountry corner of Essex County, smack in the middle of farmers’ fields that had been cleared two centuries earlier. Their project – to build the largest dam in the world across the Merrimack and force its waters down two long canals to power dozens of enormous mills – required a lot of labor, the cheaper the better. Below: Plan for Lawrence showing new dam, canals and plots for water-powered textile mills, 1845 (Source Digital Public Library of America) Here Come the Irish Refugees And who should conveniently show up but a bunch of Irish refugees who could be put to work for pennies a day? These rag-clothed, impoverished, filthy bands of people were escaping the biggest humanitarian crisis of their time. The Irish Potato famine was so severe it killed one third of the people and forced another third to flee. The Famine Irish had arrived on dangerous, unseaworthy “coffin ships” operated by unscrupulous people-runners looking to exploit the desperation of the refugees. A risky voyage across the water was nevertheless preferable to staying in Ireland. Below: A So-Called Coffin Ship Leaving Queenstown (Now Cobh) Ireland, 1848 The Irish migrants crowded the port of Boston, then made their way inland, likely on foot, looking for work. The stream of refugees began in 1847 and did not abate until the mid-1850s. At Lawrence, they formed their refugee camp – the shantytown on the southern bank of the Merrimack – and the men started working on the dam. One of these laborers was my great great grandfather, Jeremiah Driscoll, arrived from Ireland in 1851 at age 29. He worked as a laborer for the Essex Company. His home address in the Lawrence town directory, once the town was big enough to have a directory, was “Shantytown, South Side.” Other Irish built a shantytown/refugee camp on the plains above Haverhill Street, near the Spicket River. A report from 1870 stated that some shanties had to be cleared for construction of the Lawrence reservoir. One of them was 120 feet long, and made of rough boards. It housed 80 people, mostly single men but also a family who built the place and charged the boarders a half penny a day to shelter there. Below: Derogatory Cartoon Depicting Shanty Irish Irish Pride in Early Lawrence Fast forward thirty-five years or so to 1882. Lawrence has grown from a couple hundred residents to 38,000…and around half of them are Irish. Although the town is seven square miles, most folks are concentrated in walking distance of the mills lining the river, spanned now by three bridges. There are by this time over a dozen large textile mills with more being built. The Irish, though largely still poor, have survived massive prejudice and exploitation within a largely hostile Yankee society. What do they do to show their pride? Do they march in a St. Patrick’s Day parade? Hardly – the first proper St. Patrick’s Day parade in Lawrence wasn’t until the 1900s. Go to a Riverdance concert? Listen to the Dropkick Murphy’s? No: they celebrated their Catholic faith by building magnificent churches and then organizing their lives around them. Below: Interior, St. Mary's Church, erected Lawrence, Mass. 1871

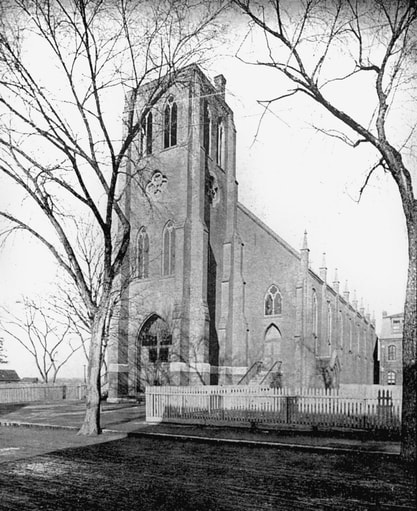

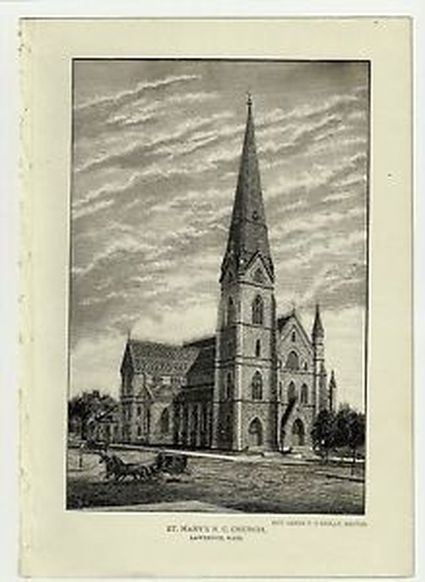

As one observer wrote, the Irish were known to spend their money on beautifying their houses of God before they beautified their own homes. Indeed, in 1882, three grand churches had been constructed of granite and brick in Lawrence – Immaculate Conception on Chestnut Street, St. Mary’s on Haverhill Street, and St. Lawrence O’Toole at the corner of Essex and Union Streets (it was renamed Holy Rosary in 1904 when the new St. Laurence O'Toole was built on East Haverhill Street). Yet at the same time, many Irish in Lawrence still lived in shanties. The last shanty was not torn down until 1894. Above: Immaculate Conception Church, Chestnut Street, Lawrence (Source: Queen City Blog). Lawrence's first permanent Catholic church, torn down 1991.The sense of Irish pride in their Church and its institutions – its grand churches, its rigorous schools, its charities like orphanages and hospitals – is captured in an 1882 book, “Catholicity in Lawrence” by Katherine O’Keefe O’Mahoney. According to Ken Skulski’s history of Lawrence, O'Keefe was “an author, lecturer and educator”. Irish-born, she graduated from Lawrence High School in 1873 (a rarity for girls, especially an immigrant girl), and then she started working there as a teacher. “Robert Frost considered her one of his favorite teachers. She was also among the first Irish-American women to lecture in New England. Her books include A Sketch of Catholicity in Lawrence and Vicinity (1882) and Famous Irishwomen (1907).” She also published a newspaper for Irish-American Catholics in Lawrence and conducted Irish classes there. She died at her Tower Hill home in 1918 at age sixty three. (Source: Ken Skulski’s Lawrence, Massachusetts.) For the about the first thirty year's of Lawrence's existence (until French Canadians started to arrive), pretty much the only Catholics in Lawrence were Irish. Reading O'Keefe's proud descriptions of St. Mary’s Church, you can get a sense of the importance of a magnificent church like this to the community:

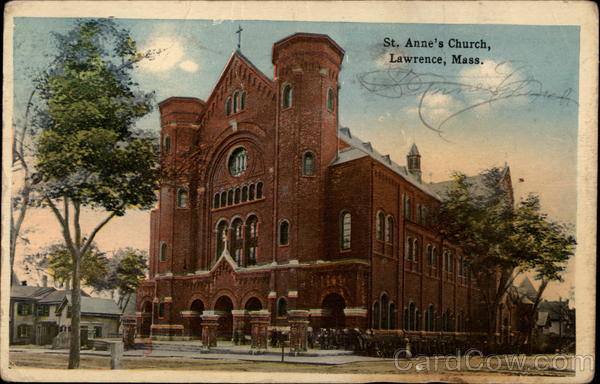

Below: St. Mary's Church, Lawrence, Mass. erected 1871 For her, the priests are towering figures, and funerals of priests are the equivalent of a funeral for a head of state. The following is from her description of the 1875 funeral of Father Louis Edge, O.S.A., who built St. Mary’s along with the Augustinian Order. She claims that 10,000 people viewed his body lying in state in his coffin in front of the altar. Note the participation of the numerous Irish social and religious organizations: “Early on Monday morning, crowds began to assemble in the vicinity of the church, awaiting the opening of the doors. The Ancient Order of Hibernians, numbering nearly 150 men, were the first to enter, and to them was assigned the East wing; after them came the Ladies’ Sodality of St. Mary’s Church, with medals and white veils. They numbered over seven hundred, and presented a beautiful appearance. The Irish Benevolent Society, headed by the Lawrence Brass Band, were the next to enter the church. They numbered nearly two hundred, and bore a silken mourning banner; they were seated in the Gospel aisle. Next came the Ladies’ Sodality of the Church of the Immaculate Conception, in white veils, similar to St. Mary’s Sodality; they had been assigned to them the West wing. After them came the Men’s Sodality of St. Mary’s Church, wearing white sashes and white crosses; they were placed in the Epistle aisle. And then came the Catholic Friends’ Society, and the Conference of St. Vincent de Paul. The church was tastefully draped in mourning, the black festoons in the galleries were relieved with white rosettes, and the mourning on the altar with small white crosses. Over the altar was a large cross, formed of blazing gas-jets; and there was a star of gas-jets [!] in front of the organ. When the clergy, forty-six in number, entered the sanctuary to chant the Solemn Office, the scene was truly grand and impressive.” She then goes to name each of the forty six priests in attendance, treating each one as a celebrity. “The architect of this magnificent structure was [Irish-born] P. C. Keely of Brooklyn, N. Y.,” she continues. He was in fact one of the preeminent architects of Catholic churches in the Northeast in the latter half of the nineteenth century. “The stone work was under the supervision of James Trainor of Boston; the wood work was superintended by James Bulger of Burlington, Vt; and the painting, as we have recently stated, was by Schumacher of Portland, Me. Its cost was over $200,000.” Given that this amount was largely raised by small donations from the commuity, it is quite an amazing sum considering that a laborer made a couple dollars a week. Later, she describes the fundraising campaign to pay for the bells of the church (weighing a total of over 10,000 lbs). The list of donors reads like a directory of Irish residents of Lawrence: John Kiley, Sr., Patrick Moran, John Brennan, Patrick Connors, Joseph Morrissey, James Kilbride, Anne O’Donnell, Mary Anne Quinn, Mary Connolly, Mary Burke, Bridget Bradley, Catherine Cushing, Thomas Regan, Mary Dowd, Mary O’Brien, Mary McCarthy, Rose Walsh, Mary Burns, Sarah McGuohan, Maria O’Sullivan, Annie M. Rafferty, Kate Reilly, Ann Mahon, Mary McGuinness, Rosanna Mulligan, Ellen McCavitt, Hannah Moriarty, Mary J. Sweeney, Ellen Ryan… The list extends for a couple hundred more names, three quarters of them obviously Irish in origin. Far more than half of them are women. Katherine O'Keefe O'Mahoney dedicated her life to promoting Irish pride. I have newspaper clippings of a lecture tour she did in 1911, about Ireland featuring numerous illustrations. She is billed as "a little woman with an enormous voice." Irish Legacy In the Catholic Church By focusing on their religion as a defining institution of being Irish, the Irish came to dominate the Catholic Church in America. “In 1880, the percentages of the clergy who were Irish American was 69 percent in the Archdiocese of Boston…Moreover, in 1886 thirty-five (51%) of the sixty-eight Catholic bishops in America were Irish born or of Irish descent. In 1920, it was still the case that two-thirds of Catholic bishops were Irish American, and in New England, that proportion was three-fourths.” (Source: American Catholics in the Protestant Imagination: Rethinking the Academic Study of Religion, by Michael P. Carroll, 2010) Later, when other Catholic immigrant groups followed - first the French Canadians, then the Poles, Italians, Portuguese, Lithuanians and (a few) Catholic Germans -- they found waiting for them a church that could provide something of a welcome, whereas the Irish basically had to create the Church in New England. Epilogue Since the early 1990s, many of the grand Catholic churches of the original Catholic communities of New England have been closed and often torn down. In Lawrence, this includes the aforementioned Immaculate Conception and St. Lawrence O'Toole, as well as half a dozen other churches. The same pattern was repeated in other urban centers: Lowell, Haverhill, Fall River, Worcester, Boston. I hope this and other blog posts will remind people that these abandoned churches were not just religious institutions, but were part of the physical culture of the immigrant groups who built them. Below: Today's St. Mary's church (Santa Maria de la Asunción)(source: church website) St. Anne's Church, the Society of Mary (Marists) and the French Canadians of Greater Lawrence3/7/2018 Above: St. Anne's Church, Lawrence. Completed 1883, closed 1991 The French Canadians in Lawrence "Although less numerous in Lawrence than in Lowell, the French Canadians still contribute an important element to the Catholic population of this city." (from Byrne's History of the Catholic Church in New England, 1899) As described in another blog post, French Canadians began emigrating to manufacturing centers in New England after the Civil War. They brought with them a concept of La Survivance, an insistence on maintaining their French language and their culture, expressed to a large degree through their own Catholic institutions: French churches and French schools. The French-speaking Canadian immigrants were comprised of Québécois from the province of Quebec; and Acadians, the descendants of French-speaking settlers of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia (many of whom were forcibly moved to Louisiana after defeat by the British in 1755, where they became known as Cajuns). A French Parish One of the first things the French-speakers did in Lawrence was to create their own parish. This was no easy task. The Augustinian order was firmly in charge of the churches on the north side of the Merrimack River. So-called national parishes (foreign-language churches that catered to specific ethnic groups) in Lawrence were usually organized as mission churches of St. Mary's parish. St. Mary's was the main "cathedral", run by the Augustinian Fathers. Thus, the German-speaking Church of the Assumption, the Polish-speaking Holy Trinity Church, the Lithuanian-speaking St. Francis and the Portuguese-speaking Sts. Peter and Paul were all mission churches of St. Mary's, and were overseen by the (Irish-dominated) Augustinians. In contrast, through the importation of recognized French-speaking religious orders, the French were allowed to have their own independent parish in the Lawrence area. Eventually, St. Anne's parish grew to encompass four churches: St. Anne's, Sacred Heart in South Lawrence, Our Lady of Mount Carmel (Methuen) and St. Theresa (Methuen). All were essentially founded by the Marist Fathers, and in most cases were run by the Marists for decades, along with St. Joseph's in Haverhill, as further described below. The Marists come to New England The order was formally recognized by the Church in 1822. It was formed after a group of soon-to-be priests led by Jean-Claude Courveille and Jean-Claude Colin made a pilgrimage to the shrine of the Black Virgin at the cathedral of LePuy in France. There, they experienced healing while praying before the statue of the Virgin. They came to believe the Blessed Mother wanted to help the Church through a society consecrated to Mary and bearing her name. The Marists' first missionary work was in the remote areas of the Diocese of Belley in southeast France. The Marist order (not to be confused with the Marianist order), first focused their American mission in Louisiana, a bastion of French Catholicism, taking charge of St. Michael's in Convent, Louisiana in 1863 and overseeing two parishes and a high school. The fact that they arrived during the Civil War did not seem to dissuade them. Until 1880, the Marists were content mainly to operate in France; however, in that year, citing the principles of the French Revolution, the government of France ordered the closure of all Catholic religious orders in France. "With the expulsion of religious orders from France in 1880, the Marist General Administration sought new opportunities for their members in the United States. There were more opportunities than they could handle, but no more than in the New England states, where French-Canadians were pouring in to find employment in the mills that had sprouted up all over the area." (From the 150th Anniversary pamphlet of the Marist Order, www.societyofmaryusa.org/pdfs/Marist150YearsofGrace.pdf) The leadership of Rev. Elphage Godin, S.M. Like Rev. James O'Donnell, O.S.A. who brought the Augustinians to Lawrence, and Rev. Andre-Marie Garin, O.M.I., who led the expansion of the Oblates in Greater Lowell, Rev. Elphege Godin, S.M., was a larger-than-life figure. Above: Father Elphege Godin, S.M. (from the Society of Mary website) Born in 1847 at Trois-Rivieres, P.O., Canada, Father Godin was ordained in 1871 for the diocese of Trois-Rivieres (Quebec), where he served for several years. He joined the Society of Mary in France in 1878. (Source: Marist 150th anniversary pamphlet.) His first assignment as a Marist was to teach at Jefferson College in Convent, Louisiana, and to preach parish missions. Able to speak English as well as French, his services as a preacher were much in demand. In the early part of 1881, he was invited to preach in Old Town, Maine, and spent some time as a missionary in Waterville, Augusta, Biddeford and Brunswick, Maine, and also in Manchester and Lebanon, N.H. In May of that year, Father Olivier Boucher, the pastor of St. Anne’s in Lawrence, MA asked his assistance. (ibid.) Completion of St. Anne's Church "In 1869 there were only four hundred French Canadians in Lawrence. They were given religious instruction in their own language in the basement of the Immaculate Conception church. [Note: the so-called "basement church" for ethnic immigrants is still a practice today in the Catholic Church.] Knowledge of the success achieved by the French Oblates in Lowell reached them, and a movement was begun which resulted in a visit from [the Lowell-based Oblate] Father Garin, and the holding of regular services in Essex Hall." "In 1882...Rev. Elphage Godin, the well-known Marist...entered upon his duties in this important centre of French Canadian colonization. Under his management the church was speedily finished and dedicated, the ceremony being performed by Archbishop Williams on Low Sunday, 1883." (from Byrne's history of the Catholic Church in New England, 1899) "It is generally agreed that St. Anne’s Parish in Lawrence was the ‘Mother Parish’ of all Marist-operated parishes in New England." (www.societyofmaryusa.org/about/history-northeast.html) St. Anne's was followed by the establishment of Marist-run missions that became four French-speaking parishes in the Greater Lawrence area: Sacred Heart (Marist-operated for 101 years), St. Joseph (85 years); and in Methuen, Our Lady of Mount Carmel (78 years) and St. Theresa (61 years).(Ibid) Below: A 2015 picture of Sacred Heart Church, South Lawrence. Source: Wikipedia The Marist Fathers provide additional French-focused churches in the area Sacred Heart An 1899 history of the Catholic Church in New England noted that St. Anne's church was bursting to the gills with worshipers. This problem was remedied with the construction of Sacred Heart in South Lawrence, which eventually became a grand complex. The first church on the site was built in 1905, apparently being replaced by the current church starting in 1916. "The oldest building on the site is the 1899 school, a three-story, highly ornamental brick structure designed in the Romanesque Revival style. The convent, rectory, and second school were built in 1920, 1924, and 1925, respectively. The ground level of the church was constructed in 1916 as a one-story brick structure, but between 1934 and 1936, the original church was incorporated into a Gothic Revival-style building constructed of polychromatic ashlar." (Source: Sacred Heart Complex Approved for Nomination to the National Register of HistoricPlaces, https://www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcpdf/pressreleases/91911_Sacred_Heart_Complex_Lawrence.pdf) Sacred Heart was closed in 2005 and has since been taken over by a Catholic-inspired group not affiliated with the Catholic church, who hold Latin masses in the facility. St. Joseph's, Haverhill St. Joseph Church was founded in 1871. It was Marist-run from 1893 for eighty five years, when Father Godin became the superior, until 1978. "In the year 1870 the French Canadians of Haverhill were numerous enough to found a St. Jean Baptiste Society, whose president was soon deputed to visit Bishop Williams [in Boston] and request the services of a Canadian pastor. Through the efforts of Father Garin, of Lowell, an Oblate priest, Rev. Father Baudin, was sent to the town on Christmas Day, 1871. A hall on Water street had been fitted up as a chapel, and in that humble edifice Father Baudin held services and baptized two children. This was the foundation of the present flourishing parish of St. Joseph." (Source: Byrne's history of the Catholic Church in New England, 1899) A more imposing edifice was constructed in 1876. "The growth of the congregation, both by new arrivals from Canada and by local increase, compelled the erection of a church and at the same time made it financially possible. December 17, 1876, Archbishop Williams blessed the edifice which stands on the comer of Grand and Locust streets, and administered confirmation to nearly a hundred persons." (Ibid.) At some later date, the church on Bellevue Avenue was constructed, which stands to this day. Father Godin served for ten years at St. Joseph, firmly establishing the Marist presence, which continued under the tutelage of that Order until 1978. The French parish was closed in 1998, when St. Joseph merged with three other formerly ethnic parishes of the Mount Washington neighborhood: St. Michael (Polish), St. George (Lithuanian) and St. Rita (Italian). The combined new parish, All Saints, is housed in the former St. Joseph's building on Bellevue Avenue. The elementary school at St. Joseph's was the subject of a legal dispute when an anti-immigrant, pro-American Haverhill School Board ordered all schools to teach only in English in 1888. At the time, instruction was being given in French by Les Soeurs de la Charité d'Ottawa (Soeurs Grises de la Croix), the so-called Grey Nuns of the Cross from Ottawa. This incident will be covered in a separate blog entry, as will be the Grey Nuns, who had a prominent role in the Merrimack Valley including running the main hospital in Lowell for a century. St. Theresa’s (St-Thérèse) and Our Lady of Mt. Carmel (Notre-Dame du Mont Carmel), Methuen Above: St. Theresa, Methuen. From Our Lady of Good Counsel website Our Lady of Mt. Carmel was built in 1922 as the first French-Canadian church in Methuen, as a "mission church" of St. Anne's In the mid-1930s, the Marist Fathers established a second mission church, St. Theresa, to serve the growing French Canadian population there. Our Lady of Mt. Carmel closed in 2000. The ministry of St. Theresa's was eventually taken over by the Augustinians, and the church was merged with St. Augustine's in Lawrence (my church growing up) to form Our Lady of Good Counsel parish. They are apparently now under diocesan tutelage. The Novitiate in Tyngsboro, Mass. In 1922, the Marists purchased a portion of Wonalancet Farm in Tyngsboro, a suburb of Lowell. You may remember from other blog posts that this is where the hapless Wonalancet, sachem of the Pennacook Indians, lived out his days under the watchful eye of Captain Tyng following King's Philips War of the mid 1670s. They initially used the historic Tyng house, pictured below (which burned down in 1981) before building a more modern set of structures. Below: The historic Jonathan Tyng house, built circa 1675, burned down 1981 Above: The Marist novitiate (for training new members of the Order), late 1960s (source http://academic2.marist.edu/foy/maristsall/essays/innovation_academy.html) After World War 2, the Marist Order decided to establish a college in the United States, and the location was either going to be in Poughkeepsie, New York, where they had a large Novitiate, or in Tyngsboro at this site. Marist College was ultimately established in Poughkeepsie. If it had been established in Tyngsboro it no doubt would have been a rival of Merrimack College, the Augustinian college in North Andover. In 1979, following a significant decline in new members to the order, the Marists sold the Tyngsboro property to Wang Laboratories, who used it for their Wang Institute until 1988, when it was sold to Boston University as a corporate campus. In 1996, a charter school, Innovation Academy, began operating on the property and they apparently bought the land outright in 2008. Legacy of Father Godin "Father Godin was a Marist pioneer who planted the seed, nurtured and cared for it while it grew and, by the time he took leave of this earth, saw it firmly established. When he began at St. Anne’s in Lawrence, MA, in 1882, this was the only house the Marists had in the whole northeastern section of the country. When he died, 51 years later, in 1931, besides St. Anne’s the province included Our Lady of Victories, Boston, MA; St. Bruno’s, Van Buren, ME, St. Mary’s High School, Van Buren, ME, St. Mary’s College, Van Buren, ME (1887 to 1926), St. Joseph’s, Haverhill, MA, Our Lady of Pity, Cambridge, MA, Sacred Heart, Lawrence, MA; Immaculate Conception, Westerly, RI, St. John the Baptist in Brunswick, ME, St. Charles Borromeo in Providence, RI, St. Remi’s, Keegan, ME, a novitiate on Staten Island, NY, and two minor seminaries: one in Bedford, MA and one in Sillery, P.Q. Canada." Sadly, the time of his death marked the beginning of a long decline of the French-speaking churches of the Marists, most of which have since closed as a result of significant postwar demographic changes. A remaining institution of prominence is the Lourdes Center in Boston. "In Kenmore Square, the Marist-run National Lourdes Bureau of America, founded in 1950 by the Marists at the request of Archbishop Richard Cardinal Cushing, and through arrangement with the Bishop of Lourdes, France, mails out an average of 22,000 small bottles of Lourdes water every month. The ministry also publishes a bi-monthly newsletter to 47,000 readers, sponsors annual pilgrimages to Lourdes, and conducts daily Mass and confessions for students, residents, hotel workers and guests, as well as shoppers and visitors to the Kenmore Square area." (Source: Boston Pilot article, February 20, 2015) Below: 1950 Banquet to celebrate the cherished Marist Fathers of St. Anne's School, held in the gym at Central Catholic High School. Source: Lawrence History Center The Marist Brothers and Education The educational legacy of the Marists in Greater Lawrence is as important as their ecclesiastical legacy. Unlike some of the other religious orders, the Marists were strongly represented by brothers, who had taken vows but were not ordained priests. The Marist brothers were typically educators at the primary and secondary level. The educational attainments in the Merrimack Valley of the Marist Brothers will be covered in a separate blog entry. Their crowning legacy was probably Central Catholic High School, which was essentially spun off of the St. Anne's School of Lawrence by Brother Mary Florentius in 1935. Below: Central Catholic High School, Lawrence. It is still a Marist institution.  Other French-Canadian Institutions in Lawrence The Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste was once to the Franco-American community what the Knights of Columbus was to the Italians or the Hibernians was to the Irish. The Social Naturalization Club was founded in 1915. Located on Lowell Street in Lawrence, it hosted prominent political leaders, like Rose Kennedy in 1962 and Mrs. Joseph P. Kennedy in 1985. Later it was located at 120 Broadway. The LaSalle Social Club on Andover Street in Lawrence was another prominent Franco-American social institution. The community also had a French paper of their own, Le Progres. [Please help me add to this list.] Above: the interior of St. Anne's church, Lawrence, 2016. It has basically been abandoned and neglected since it closed in 1991. Source photo: Eagle-Tribune

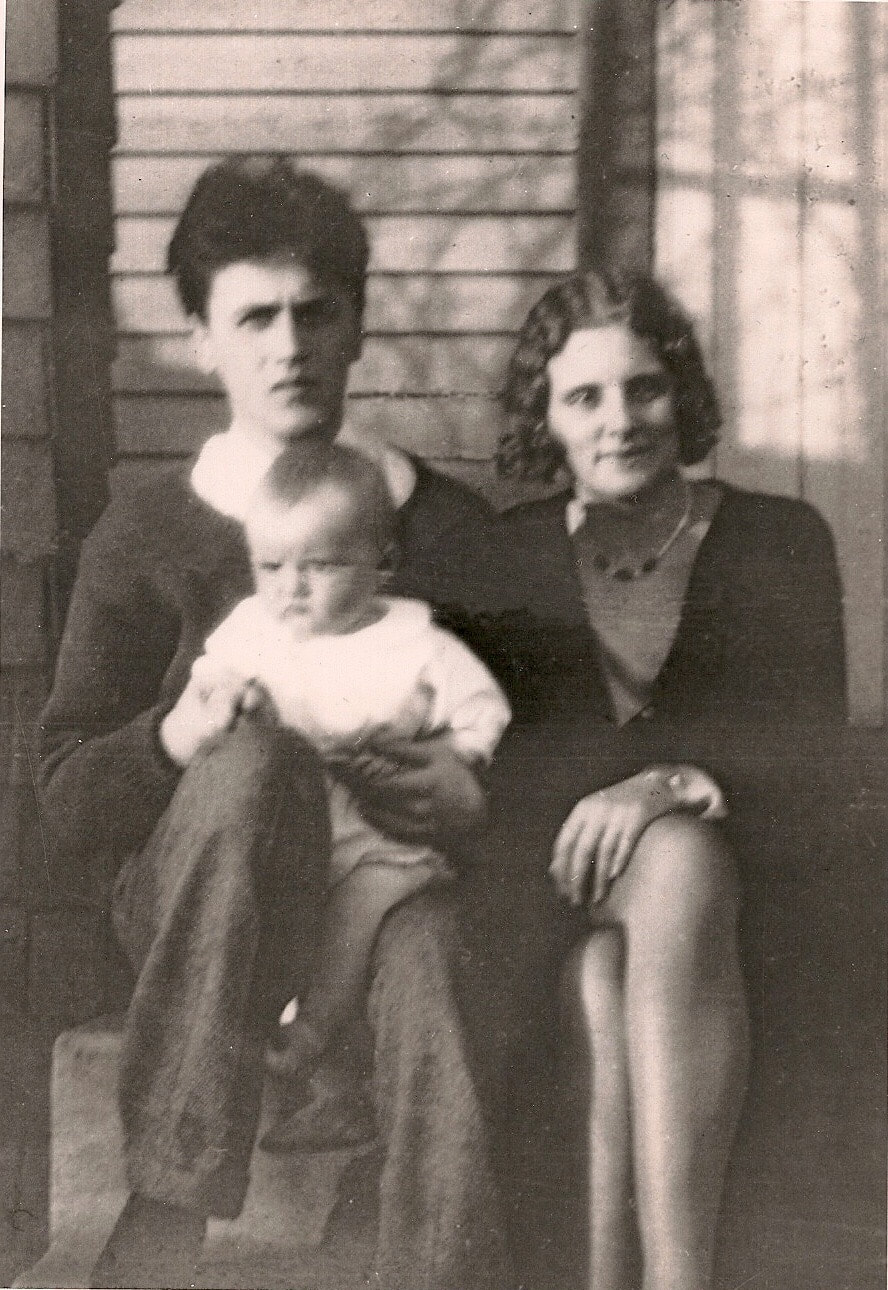

#52Ancestors challenge, week 7: My grandfather illustrates the industrial heritage of three towns2/18/2018 Below: My grandfather Clifford McCarthy, age 18, my grandmother Gladys Johnson, age 17, and my father, late autumn 1930(?). Recently, I asked my father to describe the work history of his father Clifford, who was born in Lawrence in 1912. Clifford married his high school sweetheart Gladys Johnson on his eighteenth birthday, February 3, 1930. She was four months pregnant with my father. They found a minister to do the wedding on the quick, in North Reading a few towns away. The stock market crash had been the previous October, before which Clifford's prospects seemed very different. Now, he was a married man with a family to support. Banks were failing and employers were closing. The Great Depression was descending over everything. He took his high school diploma that spring at Lawrence High and went to work. Below: The Kuhnardt Mill in Lawrence around 1930 judging by the cars in the background. This building still stands today. Source: Lawrence History Center .According to my father, "The first job of my dad’s, as I remember, from my pre-school days, was as a jig operator in the dye house at the Kuhnardt Mill by the Duck Bridge on the north side of the Merrimack River [in Lawrence]. His boss was his brother-in- law Wiliam Howarth. I heard complaints (from my mother?) that Bill picked on him." This was one of the stories of my grandfathers' employment history, working for in-laws who got him jobs. Later, he got a job with the Boston & Maine railroad through his father-in-law, who was an engineer. Years after that, in 1949, my father got a job working for his uncle Bill Howarth. It was at a dye house in Peterborough, New Hampshire. They were both working there because the mills in Lawrence were laying people off. Soon, the dye house in Peterborough also closed, and Bill Howarth moved to North Carolina to follow the textile industry south. But I digress... Because it was the Depression, there were times when my grandfather was laid off. "We received free flour from some source and my mother made "Johnny Cake” with it, which I liked," said my father. This is when New Deal programs allowed my grandfather to earn a wage. "He also worked with the WPA during the 30s. l distinctly remember a WPA arm band. I think he was involved with building side-walks, pick-and-shovel work." My father thinks he was part of the team of WPA workers that built Den Rock Park in Lawrence. Below: A bridge in Den Rock Park, Lawrence, Mass., that was likely built by WPA workers in the 1930s. The park sits at the intersection of Lawrence, Andover and North Andover My grandfather's next two factory jobs were in Andover, where by happenstance my father also was born a few years previous. "Thereafter as I remember it both parents worked a spell at the Shawsheen Mill (American Woolen Company). If this were so, my brother and I would have been living with my grandparents at 34 South. St. [Lawrence, on the Andover town line]." Below: The Shawsheen Mills in Andover in 1977, right before they were turned into apartments. Source: Andover Historical Society "I’m pretty sure the next job my father had, during World War 2, was at the Tyer Rubber Company, on Railroad St. (where Whole Foods is now). I think he was a warehouse man. As I remember he did bring home pairs of rubbers and overshoes at times. I was then in grammar school" The Tyer Rubber factory eventually was owned by Converse. Soles for their famous Chuck Taylor sneakers were apparently produced there, along with NHL hockey pucks. Manufacturing ceased there in 1977, and by 1990 the facility had been converted into apartments. As of late, there is even a Whole Foods in the front part of the facility, showing how far the town of Andover in particular has come from its quasi-industrial past! Below: My grandfather's eminently respectable parents on the occasion of their fiftieth wedding anniversary in North Andover, Mass., 1954 "The next job I believe dad had was with the B&M Railroad. I believe Grandpa Johnson, a mechanic with the B&M at the South Lawrence round house got him the job. The job was as a mechanic assistant at the round house in Boston. So this entailed a daily round trip by train. He worked there until he got laid off when the job of assistant mechanic was eliminated altogether, this was probably when Diesel engines replaced steam engines and assistant mechanics were no longer needed. I also remember him not showing on time for supper a number of nights. This occurred when he fell asleep on the train and woke up at the last stop in Haverhill. Then he would have to take the train back to Lawrence which probably got him back home about an hour after his due time." Below: My grandfather posing with other relatives in front of one of the Johnson family cottages at Hampton Beach, New Hampshire in the mid- to late- 1940s. He is lying down in front. His final job was in North Andover, at the huge Western Electric factory that was built there after World War II. "Next he worked at the Western Electric Plant in North Andover until retirement. I’m not certain what kind of work he did there, now it comes to me, I think he was a clerk in a tool crib, if you know what I mean. In any case he liked the work as I recall." "There is one more job he had," my father added. "This was as a janitor in the building [in Andover] where Phillips Academy’s school course books were sold. Now I don’t remember if he held this job before he went to work for Western Electric or after he retired. In any case I believe he worked his butt off there. It was the only time lever heard him complain about his work. He was not there for long, as I remember." Below: Osgood Landing, North Andover (largely vacant). Formerly the Western Electric Merrimack Valley Works, then an Alcatel plant. Eagle-Tribune photo. I've been told I can work like a dog, uncomplainingly. Maybe I got it from my grandfather. Even though my grandfather was a "working stiff" (as my father calls him), he regularly wore a jacket and tie when he wasn't at work. I don't know if this was a generational thing, or whether he did it consciously in an attempt to maintain some dignity despite his fairly plebeian economic status. He liked to sketch figures, including nudes copied from Playboy (an excuse to buy the magazines despite the certain protests of my fairly prim and proper grandmother). He exhibited a lot of [unmet] artistic talent that I also seem to have inherited, which is also basically unmet. Except I at least got the luxury of drawing real life nudes, when I was in the eleventh grade at Phillips Academy. Another general point: My grandfather's work history - spanning employers in Lawrence, Andover and North Andover - illustrates the free flow of people throughout an economically integrated area. One of the themes of my blog is the formerly integrated nature of "Greater Lawrence" (meaning Lawrence, Methuen, Andover, North Andover and Salem N.H.). The separate "ghetto" status of Lawrence is only a thing of the last thirty years. My father's family lived all over the Greater Lawrence area. It all seems like it was, back in the day, one big integrated area, even into the late 1970s and in my own early memory. Everyone in the Greater Lawrence area seems to know the story of the Bread and Roses Strike of 1912. It stands out for two reasons:

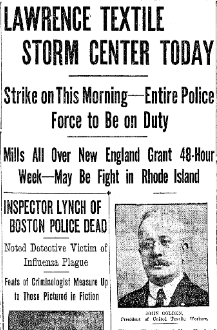

Below: Lawrence strike announced in the New York Times, February 3, 1919 How things had changed between 1912 and 1919 Even though the 1919 strike occurred only seven years after the 1912 strike, the world had changed in ways that made a successful strike of this kind more difficult.

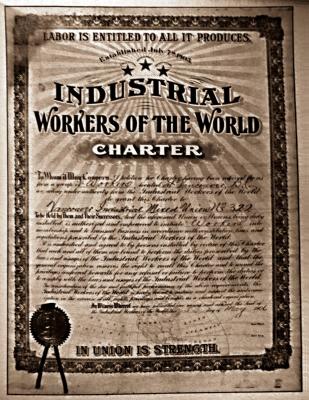

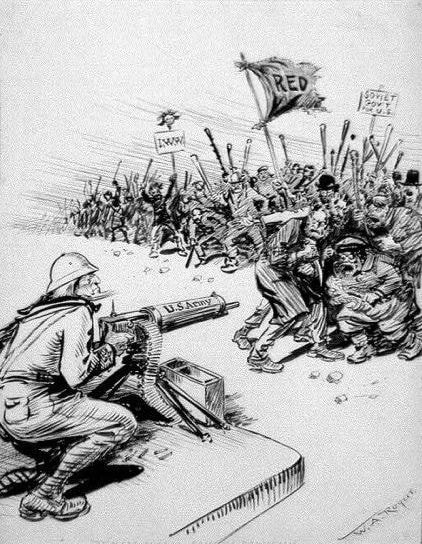

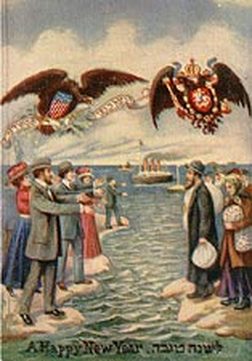

Below: The I.W.W. Charter, which reads in part "The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of the working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life." The Empire Strikes Back: The Red Scare and the Anti-Immigrant Political Climate H.L. Mencken summarized the political climate of 1919 in his book The American Scene. It was in sharp contrast to the climate in 1912, when unfettered immigration was widely tolerated because it fed the high demand of industry for cheap labor. “Returning servicemen found it difficult to obtain jobs during this period, which coincided with the beginning of the Red Scare. The former soldiers had been uprooted from their homes and told they were engaged in a patriotic crusade. Now they came back to find ‘reds’ criticizing their country and threatening the government with violence, Negroes holding good jobs in the big cities [until this time virtually no blacks had moved to northern cities], prices terribly high, and workers who had not served in the armed forces striking for higher wages. A delegate won prolonged applause from the 1919 American Legion Convention when he denounced radical aliens, exclaiming “Now that the war is over and they are in lucrative positions while our boys haven’t a job, we’ve got to send those scamps to hell.” The major part of the mobs which invaded meeting halls of immigrant organizations and broke up radical parades, especially in the first half of 1919, was comprised on men in uniform….” “As the postwar movement for one hundred percent Americanism gathered momentum, the deportation of alien nonconformists became increasingly its most compelling objective. Asked to suggest a remedy for the nationwide upsurge in radical activity, the Mayor of Gary Indiana, replied, ‘Deportation is the answer, deportation of these leaders who talk treason in America and deportation of those who agree with them and work with them.’ ‘We must remake America,” a popular author averred, ‘We must purify the source of America’s population and keep it pure…We must insist that there shall be an American loyalty, brooking no amendment or qualification.’ As [one writer] noted, ‘In 1919, the clamor of 100 percenters for applying deportation as a purgative arose to a hysterical howl…Through repression and deportation on the one hand and speedy total assimilation on the other, 100 per centers home to eradicate discontent and purify the nation.” “The man in the best political position to take advantage of the popular feeling, however, was Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. In 1919…only Palmer had the authority, staff and money necessary to arrest and deport huge numbers of radical aliens. The most virulent phase of the movement for one hundred percent Americanism came early in 1920, when Palmer’s agents rounded up for deportation over six thousand aliens and prepared to arrest thousands more suspected of membership in radical organizations. Most of these aliens were taken without warrants, many were detained for unjustifiably long periods of time, and some suffered incredible hardships. Almost all, however, were eventually released.” Given this climate of suspicion and hostility toward recent immigrants, a strike by unskilled workers from perhaps two dozen ethnicities in Lawrence would seemed destined to fail! Below: Anti-I.W.W. propaganda showing a machine-gun wielding doughboy holding off an unruly mob of foreigners. Opportunity for the Lawrence Immigrant Workers and the Reaction of the Authorities Opportunity In late 1918, the United Textile Workers of America (an A.F.L. union that mainly represented the skilled workers such as loom fixers) negotiated a reduction in the work-week in Lawrence to 48 hours. However, the deal not to reduce pay at the same time seems only to have applied to skilled workers. “In that climate of flexibility and accommodation it seems as if the Lawrence manufacturers, and the American Woolen Company in particular, wanted to discredit the unions altogether. At the very least they seemed to have wanted the workers to absorb the cost of the slack time of postwar reconversion.” (Source: Province of Reason, by Sam Bass Warner, Jr. (1988)) In other words, the management and the skilled workers colluded to pass the slack in production onto the unskilled loom operators by cutting their hours and their pay. The workers, sensing a déjà vu of what happened in 1912, when hours also were cut along with pay, went on strike. “On 3 February 1919, between 17,000 and 30,000 immigrant workers walked out of mills throughout Lawrence and began the ‘54-48’ strike. The strikers organized themselves among …different ethnic groups, with one leader per group. In addition, the strikers invited three pastors, known collectively as the Boston Comradeship (Anthony J. Muste, Cedric Long, and Harold Rotzel) as spokespeople. Ethnic stores and businesses supported the strikers by accepting coupons in place of cash. Meanwhile, the strikers boycotted stores that did not support the strike.” (From “Lawrence Mill Workers strike against wage cuts, 1919” by Kerry Robinson 16/02/2014; appearing on the site Global Nonviolent Action Database https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/lawrence-mill-workers-strike-against-wage-cuts-1919, retrieved February 10, 2018) Like the 1912, it was a strike of immigrants, by immigrants. “The general strike committee meets every morning in a dingy hall—the home, evidently, of a Syrian religious society [presumably the Marionite church?]. Approximately forty delegates come to this hall from the various language groups. Within its four walls, incontinently displaying faded pictures illustrating the Book of Revelation, Lawrence has formed her league of nations. That Syrian religious stronghold is vibrating with a new eloquence. New emotions, some of them powerful and portentous, are coming to unheralded expression. The hostile races are now allies.” (Source: Swing, Raymond. “The Blame for Lawrence.” The Nation magazine, April 26,1919.) Reaction The strike was dismissed by the A.F.L. as an unlawful “wildcat” strike. Therefore, the very union that negotiated the reduction in hours, the United Textile Workers, did not lead the strike. The walkout was covered by the mainstream press in hysterical terms involving “reds”, “commies” and “foreign anarchists”. The smelly, funny dressing, foreign-language-speaking strikers were seen as the vanguard of wild-eyed Bolsheviks. A Committee of Public Safety was organized, headed by Peter Carr, who had been a patrolman in the 1912 strike. He said “Lawrence is a city of 100,000 population and thirty-three different nationalities, most of whom are foreign. We feel this is a fertile field for the implanting of Bolshevist propaganda, and as American citizens it is our duty to suppress it.” (Source: Warner, cited above.) In other words, the response to the strike must be quick and fierce. Below: Photo of the Machine Gun used by Lawrence police to intimidate strikers, May 5, 1919. “The city administration of Lawrence enacted an aggressive approach against the strikers. Mayor John Hurley immediately began inviting in police from other towns. In less than a week, the city banned mass gatherings, restricted news coverage of the strikers, regulated inter-city travel, and kept the mills under constant police surveillance. After several cases of police beating strikers at the picket line and pro-mill infiltrators encouraging the strikers to react violently, the Boston Comradeship decided to join the picket line. At first, the presence of the clergymen deterred violent police action, but soon the police grew more intense. In one instance, several policemen cut off Muste and Long from the picket line, trapped them in an alley, beat them both, and arrested them for inciting a riot. A judge acquitted them a week later. On 18 February, a coalition of women strikers sent an appeal to Governor [later President] Calvin Coolidge to investigate excessive police brutality. Coolidge refused to meet with the coalition and sent a letter written by his secretary in defense of the local authorities’ actions. On 21 February, when a group of about 3000 strikers met in an open area near a garbage dump, two squads of police beat and then arrested strikers and injured several unaffiliated bystanders. The district court judge sided with the police and placed heavy fines on those arrested. After a lull in police violence, hostilities escalated again when the city received a machine gun from an unnamed source on 5 May to use against strikers. The machine gun was never used, but prominently displayed in front of the picket lines for intimidation. The next day, a group of men kidnapped two immigrant strike leaders, Anthony Capraro and Nathan Kleinman and left them beaten and disheveled in [Lowell].” (Source: Robinson, cited above) Were the immigrant strikers from southern and eastern Europe Bolsheviks, or was something else going on? A contemporary commentator from April 1919 explained the real story of the poor immigrant workers from places like Italy, Poland, the Balkans and Syria. “The fact that the strikers are foreigners divided among thirty-one nationalities, that few of them speak English or are citizens, and that some are boasting that in a short time the workers will own the mills, has been used as an argument that this is an attempt on the part of Eastern Europeans to impose upon America the fallacious economics of a misguided Russia. And in the light of this argument the hostility of the community, the shocking conduct of the police, and the obstinacy of the manufacturers are being justified. But the motives of the strike are not to be so precisely named or so conveniently dismissed. Had these foreigners swarmed to America imbued with the revolutionary spirit, and intrenched themselves in an industrial city to launch an attack, this strike would be truly a breach of hospitality. But they are here because American business demanded cheap labor, and many of them were even solicited by textile agents. For years the textile manufacturers have carried on a policy of gathering in the peasants of Eastern and Southeastern Europe to operate the looms of New England. These immigrants were distributed so that no more than fifteen per cent. of any one race were employed in a single mill, and the apportionment was dispassionately determined so that men and women racially hostile to one another worked side by side. This was to render organization impossible, and thus keep wages low.” (Source: The Nation article, cited above.) In other words, these workers were induced to come here because they would provide cheap labor, and their ethnicity and foreignness was used to keep them weak. Amazingly, the American Woolen Company, the main textile manufacturing company in Lawrence, had a direct hand in inviting such workers that they now faced at the picket line. “The American Woolen Company, which owns four of the eight Lawrence mills, posted lithographs throughout the Balkans depicting one of their factories as a magnificent edifice, a veritable palace of Midas, through one portal of which an army of ragged peasants marched, only to emerge from a neighboring doorway splendidly arrayed and bearing trophies—an unparalleled vision of instantaneous American alchemy. Unfortunately, actualities and visions are not allied. In red brick factories, one prodigious tier of glazed windows upon another, the European peasant has tended the looms and the spindles, and has received at the end of the week less than a living wage. The Lawrence manufacturer has not so much as justified the first unwritten premise of his posters; he has done nothing comprehensive to make Americans of these disillusioned immigrants.” (Source: The Nation article) I would really like to get my hands on a copy of the false advertising pamphlets, presumably published in Italian, Croatian, Serbian, Polish and all manner of other languages and distributed in poor rural regions to attract workers to Lawrence, where they would be kept in ethnic ghettos unable to organize with other groups of workers. Below: Poster encouraging immigration to America aimed at Russian Jews (if I can find something more on point, I will replace it) Return of the Jedi: Victory for the Strikers The immigrant workers, many of whom had been lured to Lawrence by suggestions of a better life by the employers against whom they now struck, triumphed over the Red Scare prejudices of the day and the direct hostility of the authorities. According to Robinson, cited above: “In early April, Governor Coolidge forced state arbitration between the strikers and the mill owners. The hearings held by the State Board of Arbitration and Conciliation lasted for nearly a month, but they did not lead to a compromise. However, these hearings marked the first time since the strike began that both sides directly communicated with each other. Seeing an opportunity to share credit for the resolution of the strike, the United Textile Workers [remember them??] reappeared in mid-May and negotiated with mill owners without the knowledge of those involved in the strike. The union secured a 48-hour work week as well as a 15% wage increase, more than the 12.5% increase the strike demanded. The mill owners accepted the terms since they were in need of workers and did not wish to negotiate with the strikers. Meanwhile, the strike had run out of funding. After weeks without monetary relief for strikers, organizers were ready to announce the strike as a failure. On 19 May, just as Muste prepared to announce the end of the strike, the mill owners called him to the conference with the UTW and explained the new agreement. Muste and the other organizers added a non-discrimination clause allowing the strikers to claim their former jobs. The mill owners accepted the conditions, and on 20 May 1919 the strike ended.” Above: My great grandparents Michael McDonnell and Theresa Doherty McDonnell and some of their children (with spouses), including my grandfather Joseph McDonnell standing next to and behind his mother. Michael owned a meat market and Theresa ran a boarding house across from the Arlington Mill. Michael was born in Lawrence in 1851 on Elm Street, his parents later ran a boardinghouse up Broadway just over the town line in Methuen. My grandfather was born in 1889 at a house on Broadway that straddled the Spicket River, where the little bridge is. Theresa was born in Manchester England where her parents had gone to work in the mills. Her father brought his family over from Manchester England to Lawrence by receiving $600 for fighting in the place of two different men in the Civil War in 1863. Unfortunately he never came back from that war, rather he lived out his days as an invalid in a military hospital in Bangor Maine. I think this picture was taken around 1920.

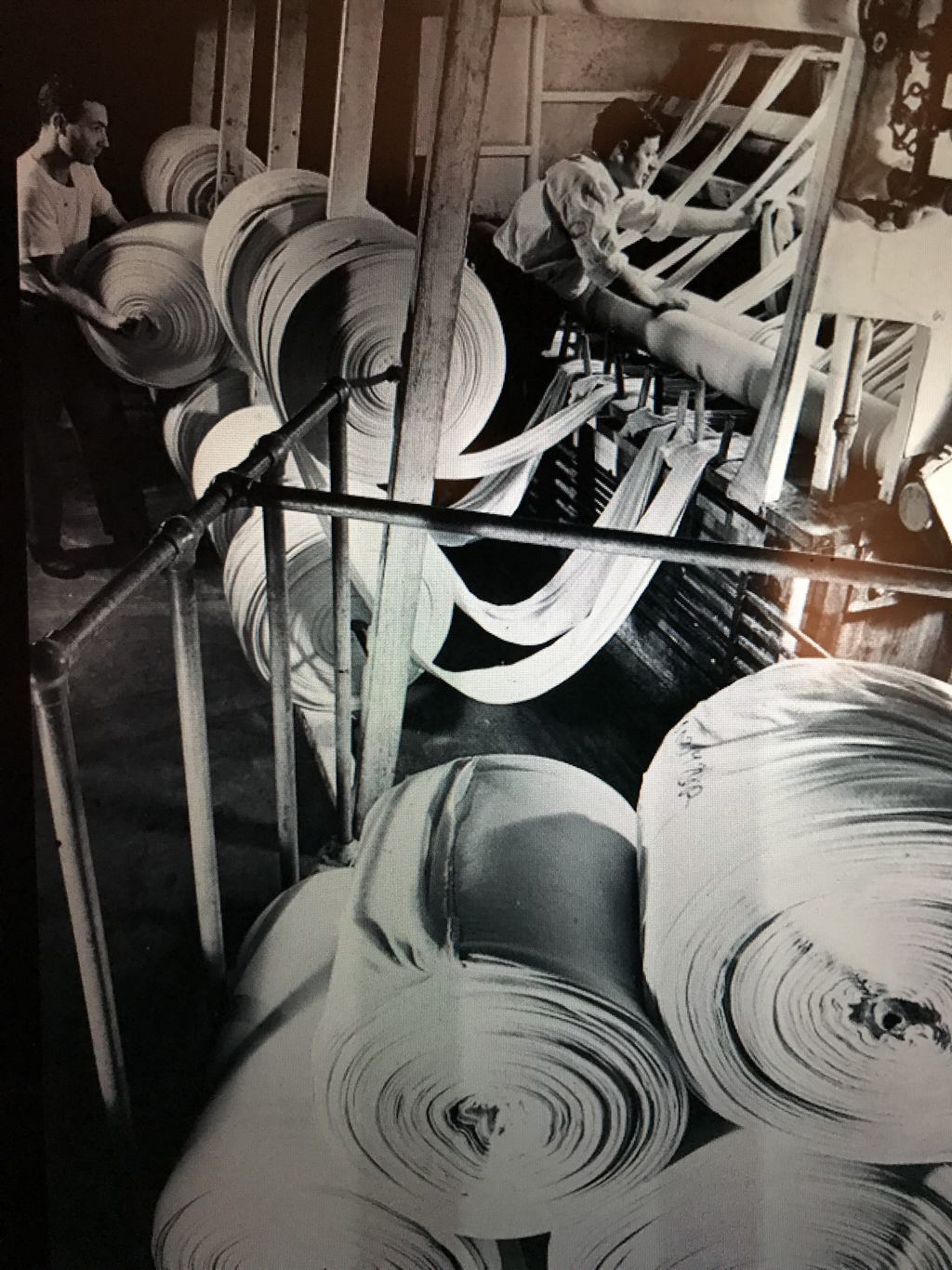

Below: The bridge where my grandfather's birthplace, 541 Broadway, used to be. Photos by me, 2016. Above: men working in a dyehouse, 1940s Poem 38 Mill Work (a mock poem testimony) by Rich McCarthy, 2011 I was a Lawrence High School student in the 40s. The mills were humming: The Wood Mill, the Ayer Mill, the Arlington, the Pacific. Most every kid had a parent or relative working in a mill. My grandfather had been a weaver here Since he left Vermont at age nineteen (When his father died and the barn burned down.) [My note: the death of his father after a balloon accident is covered in another blog post.] In High School The worst the future could hold for us Was to end up in a mill after graduation We joked about becoming a mill rat. . . no way. My poor dad was a mill rat... in the dye house. And what did I do after I graduated. I took a job. Where? In a dye house. Like dad, I became a “jig” operator It wasn’t bad work; Except for the fumes: The hydrochloric acid, the ammonia, and the formaldrahyde fumes... Whew, sometimes it was overwhelming. I met some interesting people, Like the guy who never wore a shirt And had blue birds tattooed on his chest, One on each breast. Flying towards each other. I only lasted for two months. It wasn’t for me, a kid. I didn’t have to support a family. I left for a job with a magazine distributor. I was out of the mill. It was clean work: Putting up orders for drug stores. But the pay, 65 cents an hour, Stunk So what did I do? I went back to the mill. (The American Woolen Company) One buck an hour? I couldn’t believe it With benefits to boot! A Union shop, the CIO. So there I was, A back-boy Working the second shift, (two to ten), In the mule spinning room. The temperature was hot And humid. . . 90 degrees plus Humidifiers keeping it moist So the ends would not fall. The sweat poured over our brows We all wore head bands To keep it out of the eyes It was so hot we wore pants cut off at the knee, That’s all, no shirt, bare backed And old shoes with no socks It was a nice place to be in a winter storm, tropical. Cockroaches abounded. I stuck it out for about a year. The mills were shutting down, Moving south Where cheaper labor could be found, Or so we heard. So I got “laid off". .. permanently. Lawrence fell into hard times. The textile industry, as Lawrence knew it, Collapsed. But the experience taught me About organized labor, unions. I had got a decent wage. Because the job was so dirty, We were allowed a shower On company time at shift’s end. Because of the union, When we cleaned rollers, The machinery was disengaged. (Back-boys had been killed in prior years, Crushed to death when switches Were accidentally pulled.) Funny, as I think of it, I never heard of the strike of 1912 Not from my working stiff relatives, not in school. So I’m glad this is not the case today In Lawrence. And that we now celebrate The gutsy spontaneous reaction Of exploited immigrants Who made a better future for mill workers... All workers. And I might say, for me personally, A kid back in 1949. Below: The Wood Mill and the Ayer Mill at night, south bank of the Merrimack River, Lawrence, Mass., 1940s

|

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed