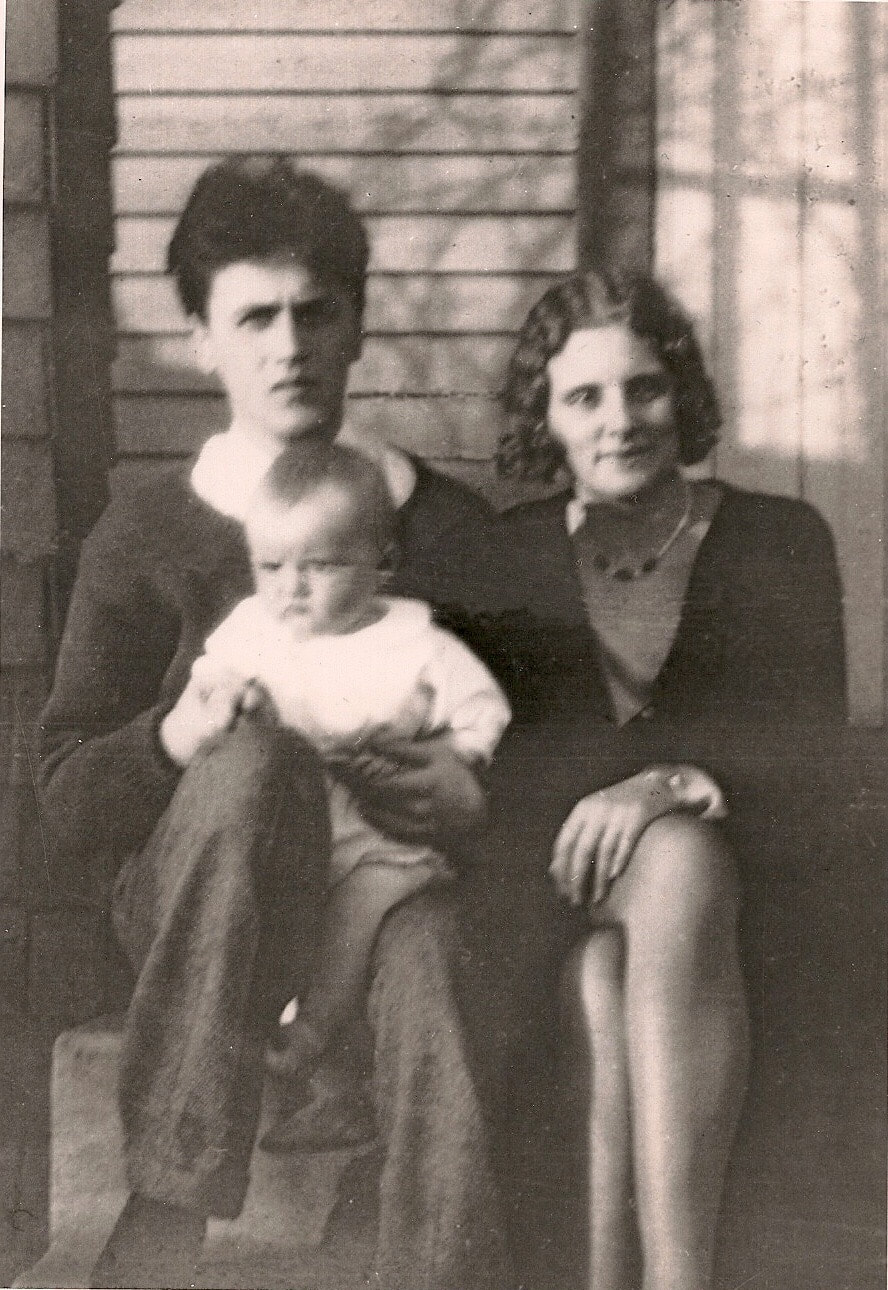

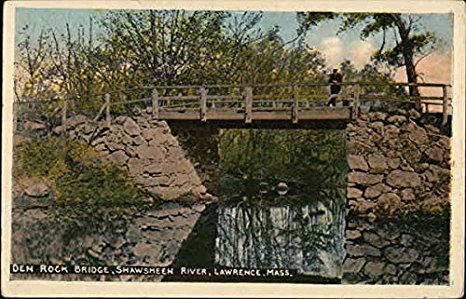

#52Ancestors challenge, week 7: My grandfather illustrates the industrial heritage of three towns2/18/2018 Below: My grandfather Clifford McCarthy, age 18, my grandmother Gladys Johnson, age 17, and my father, late autumn 1930(?). Recently, I asked my father to describe the work history of his father Clifford, who was born in Lawrence in 1912. Clifford married his high school sweetheart Gladys Johnson on his eighteenth birthday, February 3, 1930. She was four months pregnant with my father. They found a minister to do the wedding on the quick, in North Reading a few towns away. The stock market crash had been the previous October, before which Clifford's prospects seemed very different. Now, he was a married man with a family to support. Banks were failing and employers were closing. The Great Depression was descending over everything. He took his high school diploma that spring at Lawrence High and went to work. Below: The Kuhnardt Mill in Lawrence around 1930 judging by the cars in the background. This building still stands today. Source: Lawrence History Center .According to my father, "The first job of my dad’s, as I remember, from my pre-school days, was as a jig operator in the dye house at the Kuhnardt Mill by the Duck Bridge on the north side of the Merrimack River [in Lawrence]. His boss was his brother-in- law Wiliam Howarth. I heard complaints (from my mother?) that Bill picked on him." This was one of the stories of my grandfathers' employment history, working for in-laws who got him jobs. Later, he got a job with the Boston & Maine railroad through his father-in-law, who was an engineer. Years after that, in 1949, my father got a job working for his uncle Bill Howarth. It was at a dye house in Peterborough, New Hampshire. They were both working there because the mills in Lawrence were laying people off. Soon, the dye house in Peterborough also closed, and Bill Howarth moved to North Carolina to follow the textile industry south. But I digress... Because it was the Depression, there were times when my grandfather was laid off. "We received free flour from some source and my mother made "Johnny Cake” with it, which I liked," said my father. This is when New Deal programs allowed my grandfather to earn a wage. "He also worked with the WPA during the 30s. l distinctly remember a WPA arm band. I think he was involved with building side-walks, pick-and-shovel work." My father thinks he was part of the team of WPA workers that built Den Rock Park in Lawrence. Below: A bridge in Den Rock Park, Lawrence, Mass., that was likely built by WPA workers in the 1930s. The park sits at the intersection of Lawrence, Andover and North Andover My grandfather's next two factory jobs were in Andover, where by happenstance my father also was born a few years previous. "Thereafter as I remember it both parents worked a spell at the Shawsheen Mill (American Woolen Company). If this were so, my brother and I would have been living with my grandparents at 34 South. St. [Lawrence, on the Andover town line]." Below: The Shawsheen Mills in Andover in 1977, right before they were turned into apartments. Source: Andover Historical Society "I’m pretty sure the next job my father had, during World War 2, was at the Tyer Rubber Company, on Railroad St. (where Whole Foods is now). I think he was a warehouse man. As I remember he did bring home pairs of rubbers and overshoes at times. I was then in grammar school" The Tyer Rubber factory eventually was owned by Converse. Soles for their famous Chuck Taylor sneakers were apparently produced there, along with NHL hockey pucks. Manufacturing ceased there in 1977, and by 1990 the facility had been converted into apartments. As of late, there is even a Whole Foods in the front part of the facility, showing how far the town of Andover in particular has come from its quasi-industrial past! Below: My grandfather's eminently respectable parents on the occasion of their fiftieth wedding anniversary in North Andover, Mass., 1954 "The next job I believe dad had was with the B&M Railroad. I believe Grandpa Johnson, a mechanic with the B&M at the South Lawrence round house got him the job. The job was as a mechanic assistant at the round house in Boston. So this entailed a daily round trip by train. He worked there until he got laid off when the job of assistant mechanic was eliminated altogether, this was probably when Diesel engines replaced steam engines and assistant mechanics were no longer needed. I also remember him not showing on time for supper a number of nights. This occurred when he fell asleep on the train and woke up at the last stop in Haverhill. Then he would have to take the train back to Lawrence which probably got him back home about an hour after his due time." Below: My grandfather posing with other relatives in front of one of the Johnson family cottages at Hampton Beach, New Hampshire in the mid- to late- 1940s. He is lying down in front. His final job was in North Andover, at the huge Western Electric factory that was built there after World War II. "Next he worked at the Western Electric Plant in North Andover until retirement. I’m not certain what kind of work he did there, now it comes to me, I think he was a clerk in a tool crib, if you know what I mean. In any case he liked the work as I recall." "There is one more job he had," my father added. "This was as a janitor in the building [in Andover] where Phillips Academy’s school course books were sold. Now I don’t remember if he held this job before he went to work for Western Electric or after he retired. In any case I believe he worked his butt off there. It was the only time lever heard him complain about his work. He was not there for long, as I remember." Below: Osgood Landing, North Andover (largely vacant). Formerly the Western Electric Merrimack Valley Works, then an Alcatel plant. Eagle-Tribune photo. I've been told I can work like a dog, uncomplainingly. Maybe I got it from my grandfather. Even though my grandfather was a "working stiff" (as my father calls him), he regularly wore a jacket and tie when he wasn't at work. I don't know if this was a generational thing, or whether he did it consciously in an attempt to maintain some dignity despite his fairly plebeian economic status. He liked to sketch figures, including nudes copied from Playboy (an excuse to buy the magazines despite the certain protests of my fairly prim and proper grandmother). He exhibited a lot of [unmet] artistic talent that I also seem to have inherited, which is also basically unmet. Except I at least got the luxury of drawing real life nudes, when I was in the eleventh grade at Phillips Academy. Another general point: My grandfather's work history - spanning employers in Lawrence, Andover and North Andover - illustrates the free flow of people throughout an economically integrated area. One of the themes of my blog is the formerly integrated nature of "Greater Lawrence" (meaning Lawrence, Methuen, Andover, North Andover and Salem N.H.). The separate "ghetto" status of Lawrence is only a thing of the last thirty years. My father's family lived all over the Greater Lawrence area. It all seems like it was, back in the day, one big integrated area, even into the late 1970s and in my own early memory.

0 Comments

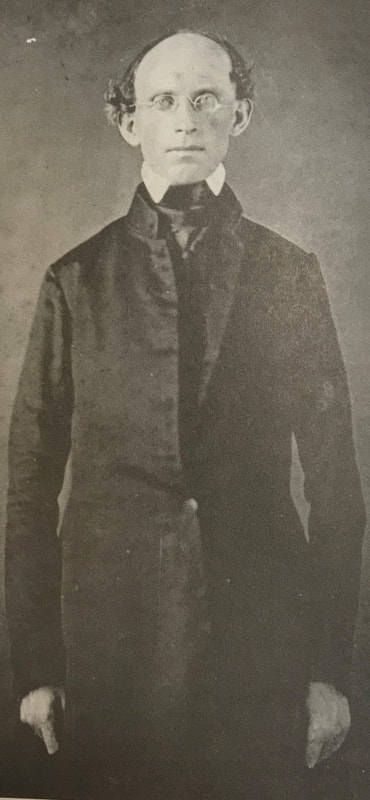

Below: Father James D. O'Donnell O.S.A., who brought the Augustinian order to Lawrence (O.S.A.= Order of St. Augustine) The story of the Augustinian "friars" in the vicinity of Lawrence, Mass. is one of the more unlikely happenings in our history. It is also a tale of a small number of dedicated men bringing great benefit to the area. Who are the Augustinians? Since the dark ages, the Catholic church has had monastic orders such as the Benedictines, in which dedicated priests and non-ordained members live a monastic existence, praying constantly to God and contemplating his wonders. In the 1200s, a different kind of order sprang up: mendicants, meaning they wandered instead of becoming hermits, and lived off local charity rather than estates. Like the monastic orders, they had priests as well as monks (essentially). The main mendicant orders are the Franciscans, named after Saint Francis of Assisi, and the Dominicans, named after Saint Dominic de Guzmán. Regardless of whether members are ordained priests or not, they are generally called friars. The Augustinian order was founded in 1256 by uniting four groups of hermits into a new order with a mendicant approach. It was never as prominent in size as some of the other orders, but nevertheless spread in missions to England, Ireland, the German speaking lands (Martin Luther was an Augustinian before he had his split with Catholicism) and elsewhere. The Augustinians come to America When Reverend Matthew Carr, a 41 year old Irishman, arrived in 1796 as the first Augustinian in America, “there was only one Catholic diocese in the whole immense territory, from Georgia to New Hampshire and from the Atlantic Coast to Mississippi." (quoting Ennis, No Easy Road: The Early Years of the Augustinians in the United States). Catholics at that time numbered about 35,000 in a total population of nearly four million. They were concentrated chiefly in Maryland and Pennsylvania (Baltimore was the sole diocese), but small groups of Catholics could be found elsewhere. Numbers of the Augustinian order in America increased slowly, to about 14 after a few decades. For the first forty years, all the Augustinians in America were Irish-born. Arthur Ennis, who wrote the preeminent early history of the order in America, surmises that their Irish background made them particularly suitable for lone efforts in their "mission":

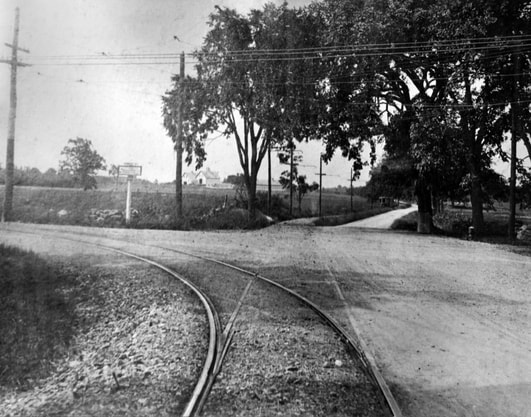

They launched their mission in Phiadelphia and built a church, St. Augustine's, that later was burned in 1844 by a nativist mob. They nevertheless persevered. They founded Villanova College around that time in a Philadelphia suburb. It would quickly become a seminary to train priests in the Augustinian tradition, and ultimately one of the more prominent Catholic universities in the United States. Below: Villanova College in 1849. Photo from Wikipedia. The Mission to Lawrence: Father James D. O'Donnell O.S.A. The Augustinian connection in Massachusetts came about through the work of James O’Donnell. The Irish-born immigrant was the first Augustinian priest ordained in the United States, in 1837, after entering as a novice in 1832 at St. Augustine's in Philadelphia. He was on the faculty of Villanova when the school opened in 1842. According to Ennis, how the Augustinian ended up in Lawrence is something of a mystery. “Father James had departed from Philadelphia early in 1848, apparently in a rebellious mood; his ambition went unsatisfied, he felt frustrated, bored with the small tasks assigned to him. He went off on a visit to Ireland, and before the end of the year he was back, hard at work now in Lawrence, assigned there by Bishop Fitzpatrick of Boston. How this came about is a puzzle. Although there is no record of permission given to him by his Augustinian superiors, he evidently received approval for his move to Lawrence, granted perhaps after the fact, for he would not otherwise have been acceptable in the diocese of Boston." Lawrence at that time had just been established and was a boomtown. Roads were being laid out, institutions were being constructed, such as libraries and schools, and mill buildings were going up everywhere. Catholic immigrants were pouring in. Destitute Irish laborers fleeing the potato famine had taken up vacant land just south of the river and soon had built over a hundred shanties. They were put to work, digging the canals and constructing the great stone dam, the largest dam in the world, that provided water power to the mills. According to a census taken in 1848, the town had a population of nearly 6,000, up from a couple dozen Yankee farmers two years earlier. Of that number, 2,139 were natives of Ireland, and presumably the vast majority of them were Catholic. Father James immediately embarked on a building spree to meet the needs of the burgeoning Catholic population. Although a small wooden church, Immaculate Conception, had been built in 1846 by a Father Charles Ffrench (not a typo), another mendicant friar (albeit a Dominican), Father James surmised the need for more houses of Catholic worship. He arrived in Fall of 1848 and promised that he would be saying Mass in a new church on New Year’s day. When the day came, the new church was barely walls and timbers, with snow falling through the open roof. However he said Mass as promised and a few months later the church was finished, being the first St. Mary’s. He financed the construction efforts with a church bank, taking deposits from his parishioners at interest. A few pennies a month from each of the couple thousand members added up, and lucky for him there were no bank runs (although in 1882 there was a run on St. Mary’s bank when a large number of depositors sought to withdraw their savings during a labor strike)(Source: Ennis). O'Donnell barely had time to rest before he set about building a larger church, this time of stone, on the same site. The construction took place all around the little wooden church, and then the new, larger church was completed, the wooden structure was torn down and its beams were used to construct a rectory for the priests. Then, in 1861, O'Donnell constructed a massive replacement church, also called St. Mary's, after buying up land on both sides of Haverhill Street. This structure, which burned down in 1967, became the St. Mary's school following the construction of the (still-standing) St. Mary's "cathedral" nearby on Haverhill Street in 1871. Below: Photo from the Lawrence Public Library archives of the original St. Mary’s granite building, which became the second St. Mary’s school. This building was destroyed by fire in 1967, after which time the high school became solely a girl's school. St. Mary’s High School for girls began instruction in 1880 and closed in 1996, when nearby Central Catholic high school began admitting girls. St. Mary’s Elementary School closed 2011. Source: Louise Sandberg, library archivist, on her Queen City blog. Father James also organized the parochial school system with the help of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur and began ministering to some of the nearby Catholic communities. He regularly visited Methuen and Ballardvale (the main mill section of Andover at that time). On November 22, 1853 he blessed the first Catholic chapel in Andover. This church, St. Augustine's, survives and prospers to this day under the auspices of the Augustinian order, in a later-constructed building. O'Donnell's strenuous activity must have taken a toll on his health, for he died quite unexpectedly on April 7, 1861, only days before his fifty-fifth birthday. No cause of death is recorded, but his illness was sudden and brief for on the previous Sunday he had presided at Easter services. The Augustinians in Lawrence after James O'Donnell's near one-man-show Following the untimely death of Father James, a series of prominent Augustinian priests ran things in Lawrence, although for most of the following decades they were only two or three on the ground. These included Rev. Ambrose McMullen, O.S.A. (in Lawrence 1861-1865), Rev. Thomas Galberry, O.S.A (in Lawrence 1867-1872 I believe), Rev. John Gilmore (in Lawrence 1872-1875). I say prominent mainly because they later went on to do great things, such as serve as president of Villanova (Mullen and Galberry), or become a bishop of the diocese of Hartford (Galberry). Mullen returned to the area after his tenure as college president, serving as pastor of St. Augustine's in Andover, where he died on July 7, 1876 at age 49. Photo below: Rev. Ambrose McMullen, O.S.A. Father Mullen was first stationed at St. Augustine's in Philadelphia and later in Lawrence, Massachusetts, where he continued the work of Father James O'Donnell. From 1865 to 1869, he was President of Villanova College. His next assignment was to St. Augustine's, Andover, Mass., until his death in 1876. He is buried in Saint Mary's Cemetery in Lawrence, Massachusetts. The construction of St. Mary's was followed by the organization of numerous churches in Lawrence in addition to that church and Immaculate Conception. Six other Catholic churches in north Lawrence were ultimately under the care of the Augustinians, many serving immigrant communities: St. Francis (Lithuanian Catholic) on Bradford Street, dedicated 1905 closed 2002; Sts. Peter and Paul (Portuguese Catholic) on Chestnut Street, dedicated 1907 closed 2004; Church of Assumption of Mary (German Catholic) on Lawrence Street (where I was baptized as an infant in 1971), dedicated 1897 and closed 1994; Holy Trinity (Polish Catholic) on Avon Street, dedicated 1905 closed 2004; St. Laurence-O'Toole, dedicated 1903 closed 1980; and St. Augustine's on Ames Street, where I went to Mass as a child, merged with St. Theresa's of Methuen, 2010, with masses celebrated once weekly in the St. Augustine's building, now called a chapel. Here is the Boston archdiocese list of merged or suppressed churches. My great-grandfather's nephew, Rev. Daniel Driscoll O.S.A. (1886-1963), was educated at Villanova and finished up his priestly vocation at St. Mary's in Lawrence. The 1940 federal census lists him living in the St. Augustine's rectory on Ames Street as the head priest along with two other priests; he later was at St. Mary's. Below: Photo of my great-grandfather's nephew, Father Daniel Webster Driscoll, O.S.A. (circa 1950?) of Lawrence, Mass. Served as priest at St. Augustine's, Lawrence, then St. Mary's. Founding of Merrimack College, North Andover, in 1947 Merrimack College was founded in 1947 by the Order of St. Augustine at the invitation of then Archbishop of Boston, Richard Cushing. It was founded to address the needs of returning G.I.s who had served during World War II, and is the only other Augustinian college in the U.S. besides Villanova. Rev. Vincent A McQuade, O.S.A., was a driving force behind the establishment of Merrimack and served as its first president. During his twenty two years in that position, he developed the college into a vital resource in the Merrimack Valley. "Vincent Augustine McQuade was born in Lawrence, Massachusetts on June 16, 1909, the son of Owen F. and Catherine McCarthy McQuade. The product of a Catholic home, Father McQuade was a son and a brother who attended St. Mary’s Grammar School, graduating in 1922. In August the same year, at age thirteen, he was received as a Novice in the Order of Saint Augustine. A graduate of Villanova University in Philadelphia, Father McQuade was ordained in 1934 and received his Master’s and Doctoral degrees from Catholic University in Washington, D.C. Father McQuade was a member of the faculty at Villanova from 1938 through 1946 who served in a succession of administrative roles including Acting Dean and Assistant to the President. Father McQuade also held a number of positions that required him to minister and advocate for servicemen, befitting the future founder of a college conceived in part for returning veterans." (source: https://merrimack.smugmug.com/History/The-College-on-the-Hill/) Below: Future site of Merrimack College, Wilson's Corner, North Andover, 1946. Source: same Today, Merrimack College has:

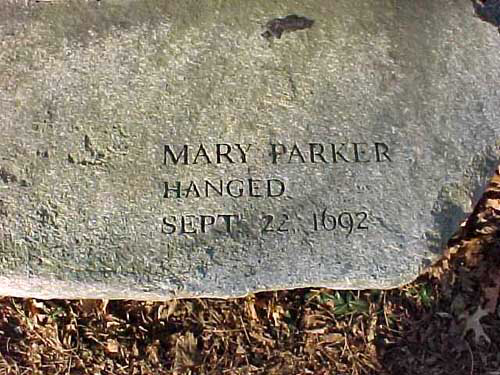

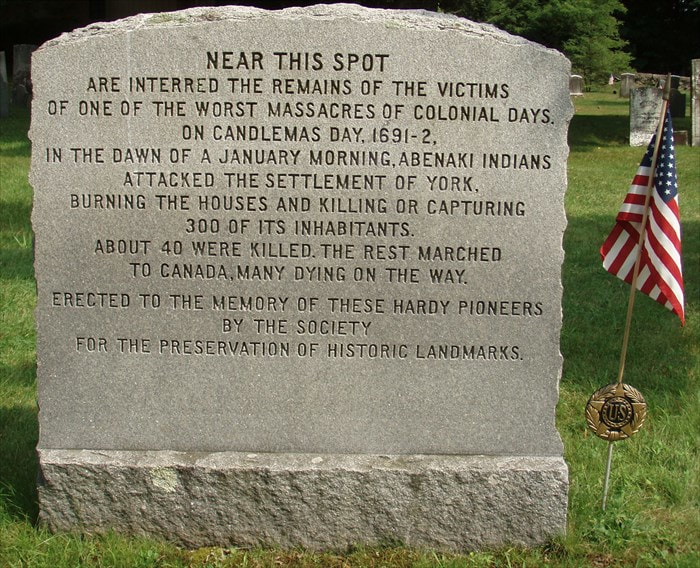

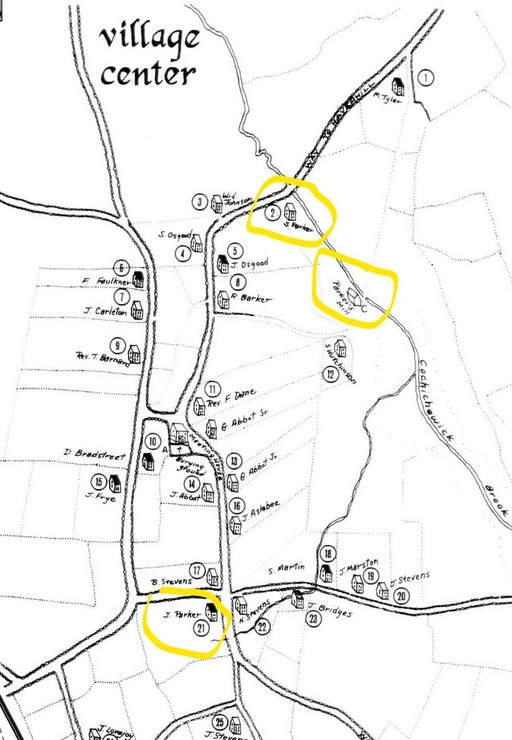

Photo below: Merrimack College, North Andover, "a selective, independent college in the Catholic, Augustinian tradition whose mission is to enlighten minds, engage hearts and empower lives". Source: college website. If you have read my biography, you’ll know my genealogical story. Some ancestors of mine showed up from England in the early 1630s, settled briefly at the mouth of the Merrimack River in Salisbury, Newbury and Ipswich, then quickly moved to the (then) frontier towns of Haverhill and Andover about twenty miles upriver. Then they stayed there…for centuries. Later, those towns got divided into other towns: Andover into North Andover and the south part of Lawrence; Haverhill into Methuen and the north part of Lawrence as well as a bunch of New Hampshire border towns – Plaistow, Hempstead, Atkinson, Salem. Please see my chart about the division of Merrimack Valley towns. Other ancestors of mine kept showing up over time – Irish, Scandinavians, Scots – and they also stayed and mixed with each other and the general population. Based on extensive genealogical research, the vast majority of ancestors of mine who were born in the United States or the colonies seem to have been born in Haverhill or Andover or in a town set off from them. In genealogy there are always surprises. And I’m not even getting into the “surprises” made possibly by the very latest genealogical tools, DNA testing. (“What do you mean grandpa’s not really my grandpa??”) Never in a million years did I expect to find that family members possibly owned a slave. Background The setting for coming across this information is quite dramatic: the Indian raid on Haverhill on August 29, 1708, which was part of Queen Anne’s War between the English and the French and their respective Native American proxies. See Glossary for more on Queen Anne’s War. I was researching Samuel Ayer, my eighth great grandfather, born 1654 in Haverhill. He was a yeoman, a man of property. He succeeded his father as a member of the committee for the control of the common lands of the town. He was killed while trying to free prisoners taken by Indians after the attack on Haverhill on August 27, 1708. On that day, Haverhill, then a compact village of about thirty houses, was attacked and almost entirely destroyed by well over two hundred Algonquin, St. Francois and Penobscot Indians under the direction of the French forces from Arcadia (Arcadia was the French-controlled area that was renamed New Brunswick when the English took it). Sixteen of Haverhill’s inhabitants were massacred with swords and tomahawks, including Rev. Benjamin Rolfe and family [being a puritan Reverend was a big deal in those days]. However, Rolfe’s female African slave, named Hagar, and two of Rolfe’s children survived by hiding under barrels in the cellar. When the Indians and French retreated, they were followed by Captain Samuel Ayer with a company of twenty men who, though out-numbered thirteen to one, attacked them, killing nine of their number and retaking several prisoners. The Captain was shot in the groin and died just as his son reached the scene with reinforcements. Interesting story. Attacks on frontier towns by Indians and their French manipulators was common enough, though, although now mostly forgotten. The Maine frontier was particularly hard-hit in the late 1600s: Kennebunk in September of 1688, Salmon Falls – now Berwick Maine – in March 1690 (in which about 90 English villagers were killed or imprisoned for ransom), Wells in June 1691, and York in January 1692 (in which 200 English villagers were killed or imprisoned for ransom). So: Indian raid, schmindian raid. The detail that jumped out at me was rather: the minister had an African slave?? I am not a relative of Rolfe’s, as far as I can tell. However, the slave detail got me focused on whether any of my Haverhill ancestors from this time also owned slaves. It turns out that in 1705 there were about 550 African slaves in Massachusetts, mainly received in exchange for Indians sent into slavery in the West Indies after being captured in war by the English colonists starting at the time of King Philip’s War in 1675. Slaves in Haverhill Chase’s History of Haverhill (which should be required reading for all residents of Haverhill and its offspring-towns) says the following about slaves: We believe that the earliest distinct allusion to “servants” we have met with in the records or traditions of this town, is the record of the death of “Hopewell, an Indian Servant of John Hutchins,” in 1668. The next, is found in the account of the remarkable preservation of Rev. Mr. Rolfe's children, by his "negro woman," Hagar, in 1708. Hagar "owned the covenant, and was baptized," with her children (two sons and one daughter) by Rev. Mr. Gardner, in 1711. In 1709, the house of Colonel Richard Saltonstall was blown up, by “his negro wench,” whom he had previously “corrected.” In 1723, Rev. Mr. Brown had an Indian servant, as may be seen from the following entry in his book of church records: — “Baptized Phillis an Indian Girl, Servant of John & Joanna Brown.” In 1728, Mr. Brown baptized “Mariah, negro servant of Richard Saltonstall.” In 1738, Rev. Mr. Bachellor baptized “Celia, Negro child of John Corliss.” In 1740, he baptized “Levi, Negro child of Samuel Parker.” In 1757, he baptized “Dinah, negro child of Samuel Haseltine ;” and, also, “Lot & Candace, negroes belonging to Richard and Martha Ayer.” In 1764, he baptized “Gin, negro Girl of Peter Carleton.” Mr. Bachellor had himself a negro servant, as we find, in the church book of records of the West Parish, under date of March 24, 1785, the following entry among the deaths: — “Nero, servant to ye Revd Mr Bachellor.” There is a tradition that he had a negro named “Pomp,” who is said to have dug the well near the old meeting-house. As the story goes, just before setting out for an exchange with a distant minister, Mr. Bachellor set Pomp at work to dig the well, and gave him positive instructions to have it done by the time he returned. Pomp labored diligently, and with good success, until he came to a solid ledge. This was too hard for his pick and spade, and poor Pomp was greatly perplexed. His “massa” [cringe] had directed him to have the well done when he returned, but how to get through the solid rock was more than Pomp could tell. While in this dilemma, a neighbor happened along, who advised that the ledge should be blasted with powder, and kindly instructed Pomp how to drill a hole for the blast. The latter, much pleased at the prospect of getting his job finished in season, worked vigorously at his drill, and soon had a hole nearly deep enough, when he suddenly struck through the ledge, and the water commenced rushing up through the hole with such force, that he was obliged to scramble out of the well as fast as possible, to escape drowning. It is said that the well has never been dry since. [Pomp seems to have been a popular name of African slaves – Pomp’s Pond in Andover was named after one…see below.] From Rev. Mr. Parker's book of church records, in the East Parish, we find that, in 1750, he “baptized Jenny, the Servant child of Joseph & Mary Greelee;” in 1758, “Phillis, the negro child of Ezekiel and Sarah Davis;” and, in 1764, “Meroy, the negro child of Seth & Hannah Johnson.” From the official census of 1754, wo find that there were then in this town sixteen slaves, “of sixteen years old and upwards.” In 1764, the number was twenty-five. From a partial file of the town valuation lists, from 1750 to 1800, we learn that the following persons in this town owned slaves. It is worthy of note, that with the very few exceptions noted, but one negro was owned by each person: — 1753. John Cogswell, John Dimond, Benj Harrod, John Hazzen (2), Col Richd Saltonstall (2), Wm Swonten (2), John Sawyer, Saml White. These were all in the First Parish. 1754. In the East Parish, Joseph Greelee, Wm Morse, Amos Peaslee, Timothy Hardey. 1755. In the First Parish, John Cogswell. In the West Parish, John Corlis. 1759. In the First Parish, Moses Clements, Samuel White, Samuel White Esq, Thos West. In the West Parish, Joseph Haynes. 1761. In the West Parish, Samuel Bacheller, Joseph Haynes, 1766. In the First Parish, Moses Clements, Nathl Cogswell, James Methard, Samuel White, Samuel White jun (2), John White. jun 1769. In the East Parish, Dudley Tyler. 1770. In the First Parish, Moses Clements, James Methard, Samuel Souther, Saml White, Saml White jun (2), John White. 1771. In the First Parish, Jona Webster, Saml Souther, John White, Saml White Esq.f James Methard, Moses Clement, Enoch Bartlett. In the East Parish, Dudley Tyler. 1776. In the East Parish, Wm Moors, Dudley Tyler. This is the latest date we find "negroes," or "servants," entered in the valuation lists in the town. In one list, the date of which is lost, but which was apparently somewhere between 1750 and 1760, we find the following : — Robert Hutching, Moses Hazzen (2), Robert Peaslee (2), John Sanders, John Sweat, Saml White, Saml White jun, Christ; Bartlett, John Clements, Joseph Harimin, Joshua Harimin, Eadmun Hale, Daniel Johnson, Jona Roberds, Wm Whitiker. We are informed by Mr. James Davis, that his father, Amos Davis, of the East Parish, owned two negroes named Prince and Judith, whom he purchased when young, in Newburyport. The bill of sale of them is still preserved in the family. Prince married to white woman, and, after securing his freedom, removed to Sanbornton, N.H., where he has descendants still living. Judith remained in the family until her death. Deacon Chase, who lived in the edge of Amesbury, not far from the Rocks' Village, also owned a negro, named Peter, who is remembered by many persons now living [Chase’s History was published in 1861]. After the death of his master, he passed into the possession of a Mr. Pilsbury, with whom he lived until his death. William Morse, of the East Parish, had a negro servant, named Jenny. We also learn of one in the family of Job Tyler in the same Parish. So ends Chase’s summary of the slaveholdings in Haverhill over the years. Slaves in Andover There were also slaves in Andover at the same time, although I can’t presently find such a comprehensive investigation as the one above for Haverhill. According to Bill Dalton in an article for the Andover Townsman in 2013, “The often repeated tale of Andover slaves Pompey Lovejoy and Rose Foster is a relatively pleasant one, as slave histories go. So, let’s start the story of slaves in Andover by visiting their legend. Pompey, shortened to “Pomp,” was born a slave in 1724, and he was owned by Captain William Lovejoy, who gave Pomp his freedom upon his death in 1765. Pomp married Rose Foster, a freed slave, and the two of them were granted land near a pond, which today is named after him. Well into middle age, Pomp served on the Colonialist side in the Revolutionary War, and he was granted a pension for that service. Pomp and Rose were well-liked in town. Rose’s served election day cakes and other refreshments during town meetings and any other elections, and Pomp played the fiddle while white folks danced. Neither Pomp nor Rose were allowed to vote as they were Negroes. When Pomp died at age 102, it was said he was the oldest man in Essex County. His epitaph in the South Parish Burial Ground reads: “Born in Boston a slave/ Died in Andover a Free Man/ February 23, 1826/ Much respected and a sensible amiable upright man.” Rose died not long after at age 98. By all evidence, they lived the good life and were well-loved by townspeople and Phillips students who frequently visited them. Another slave named Pompey didn’t fare so well. In 1795 he was hanged for murdering his master, Capt. Charles Furbush. This Pomp is said to have suffered from insanity that occasionally required him to be kept under guard. Historian Sarah Loring Bailey said of Furbush’s murder, “...the community was [so] shocked at the act and its circumstances of horror [that] the negro was sentenced to the extreme penalty of the law.” Dalton also writes that Reverend Samuel Phillips, founder of Phillips Acadamy, owned slaves. He and his wife each had a personal attendant (this last detail is from Sarah Loring Bailey’s history of Andover). Here are some other details from his article: In the Old Burying Ground near North Andover Commons, there is a headstone that reads: In Memory of Primus/ Who was a faithful servant of Mr. Benjamin Stevens Jr/ Who died July 25, 1792/ Aged 72 years, 5 months, 16 days. In the South Parish Burying Ground is the grave of the last slave born in Andover, Rose Coburn, wife of Titus Coburn. The stone says she died at age 92 in 1859. Historian Bailey, who must have known Rose, says of her, “She was a slave born in Andover and the last survivor of all born here in that condition. A pension was paid to her as the widow of a soldier of the Revolution. She was a person of great honesty, veracity, and intelligence and retained all her facilities in a singular degree to the last.” Sometimes a passing sentence in a book reveals a lot, and leaves more questions unanswered. In Sarah Loring Bailey’s history of Andover, she says about the South Parish Church, “In 1766 it was voted that ‘All the English women in the Parish who marry or associate with Negro or Melatto-men be seated in the Meeting-House with the Negro-women.’ Fascinating for so many reasons: (1) the meetinghouse/church still maintained the puritan practice of separating men and women for worship almost on the eve of the American Revolution; (2) seating was also segregated based on race; and (3) there were mixed race marriages. So What About my Ancestors? Now that the stage is set, what about my ancestors? I’m afraid that the record is still ambiguous. A website called olddeadrelatives.com has an entry for Captain Samuel Ayer, slaveowner. However, it has as parents for this Samuel Ayer “Coronet Peter Ayer” and “Hannah Allen” whereas I have the following people as the parents of the Samuel Ayer who was killed in the 1708 raid: Robert Ayer and Elizabeth Palmer. So it might not be the same Samuel Ayer, although perhaps a cousin. More investigation is needed. The sole citation given by olddeadrelatives.com is A Genealogical Dictionary of The First Settlers of New England Before 1692; Savage, James (Little, Brown and Co, Boston, MA. 1862). I will have to track down this book, which apparently does have a description of slave ownership in Massachusetts at this time. I also note the name Peaslee among the list of Haverhill slaveholders in the Chase book, as well as other Ayer slaveholders (Richard and Martha). Then there is the surname Lovejoy attached to the slave for whom Pomp's Pond is named. I am descended from a Peaslee of Haverhill and a Lovejoy of Andover, so these slaveowners might be relatives of mine. Something else to investigate... That’s the thing about genealogical research: you can never finish, there is always another question to answer. A statue of a saint stood benevolently on the widow-shelf surrounded by plants basking in the sunlight. He was about ten inches high and composed of a dark brown, heavy, rough-cast metal. “Who is that?” I remember asking my mother, when I was about five years old. We learn so much about our world at our mother’s knee. I was a big beneficiary of having a teacher for a mother. “St. Francis of Assisi,” she told me. “My favorite saint,” she added, “along with Teresa the Little Flower.” Who was this St. Francis, hand raised, looking down upon us from the shelf? The impression I got of him, from my social-justice pursuing, liberation theology-espousing, National Catholic Worker-subscribing parents, was of a barefoot, soft-talking, sentimental, free-thinking, anti-authoritarian, tree and animal hugger and social activist. “He loved the animals, and the children, and most of all the poor,” she told me. Soon we were supplementing our Sunday worship with journeys with men and women who strove to live like St. Francis. The Christian Formation Center was founded in the late 1960s next to the St. Francis Seminary on River Road, West Andover, near the Tewksbury town line amid expansive fields and lawns that had once been a dairy farm. Down the slope, the Merrimack River ambled in the distance. The seminary there trained Franciscan priests from 1930 until 1977. The grand, colonial-looking building of the seminary was finally torn down last year to make way for high-end senior housing. Across the street stood the monastery of the sisters of Poor Clare, a female monastic order named after St. Clare of Assisi (1194-1253), the first follower of St. Francis of Assisi (1182-1226). The female Franciscans, nuns, and the male Franciscans, monks and priests, pursued their “formation” into the Franciscan way, alongside “secular” Franciscans, laity who were neither monastic nor clergy. And this is where the Christian Formation Center came in. Formation took many decades, and they worked together at attempting to achieve perfection into the ways of St. Francis. In contrast to the seminary and the monastery, the formation center was a modern structure, set way back from the road among the fields. It was supposed to offer alternative forms of religious expression, albeit within the teachings of St. Francis. Remember, this was the golden period after the reforms of the second Vatican Council, when modernization and making the Church more relevant to the times was the order of the day. Pope John XXIII, who had ushered in Vatican II, had himself been a Secular Franciscan before he became a priest, living an idealized life of poverty and holy contemplation as worked for the poor. Unlike our local church, St. Augustine’s on Ames Street in Lawrence, the Christian Formation Center had no pews for Mass. Seating was auditorium-style, with individual seats arranged in a curvature around an altar that was more like a central performance stage. I think kids sat cross-legged on the floor in front, where the priest and assembled clergy fawned over them. Fully-robed Franciscan priests and brothers walked the outdoor gardens and breezeways, and, when it was time for Mass, they mounted performances of tambourines, acoustic guitars and folk melodies, along with the nuns. We would regularly sing Michael Row the Boat Ashore when we attended Mass there. (In case you don’t know this song, is is a Negro Spiritual that was popular in the civil rights movement and among left wing activists.) These were no crusty parish priests, giving tired homilies and leading the traditional choir. Apparently, the Christian Formation Center sought to attract non-Catholic Christians to its worship, either in an ecumenical outreach that was in the spirit of the times, or as part of some kind of subtle Catholic proselytizing, I don’t know. The whole zeitgeist of the service was quite different from the other Catholic churches where I had attended worship. For one thing, there was speaking in tongues, and a lot of Catholic Pentecostals. Are there Catholic Pentecostals anymore? Other mounting was also going on. As my mother tells it, the Seminary closed in 1977 shortly after we started going, “because a bunch of the nuns got pregnant by a bunch of the seminarians and they all left the religious orders to get married.” I have no idea if it’s true, but we did stop going to the Christian Formation Center by about 1980 if memory serves me. As a secular formation center not tied to the clergy, it could in theory continue despite the closing of the seminary…and the nuns are still there, although they have a small, modern monastery now. Their old facility was torn down to make way for luxury housing, although the Christian Formation Center building survives to this day as a private school for autistic children. Anyway, within a few years, the entire tone of the Church changed. Although there was no return to the Latin Mass, within the Church the social justice trends of the 1970s gave way to the sexual politics of the 1980s, as Pope John Paul II led a traditionalist backlash. The last time my mother set foot in a church for Mass, other than for funerals or weddings, was when my younger sister had the sacrament of penance (first confession) at St. Augustine’s in 1984. After the CCD teacher repeatedly gave lessons on the place of women (in the home, subservient to men), my mother walked up to him after class to give him a piece of her mind. Things in her church had been changing for some years, and this must have been the last straw. She never went back to Mass, although she still has her statue of St. Francis looking over her in the kitchen. Above: Photo of the Melmark School, River Road, Andover, Mass., the former Christian Formation Center. Photo source: Melmark School website.

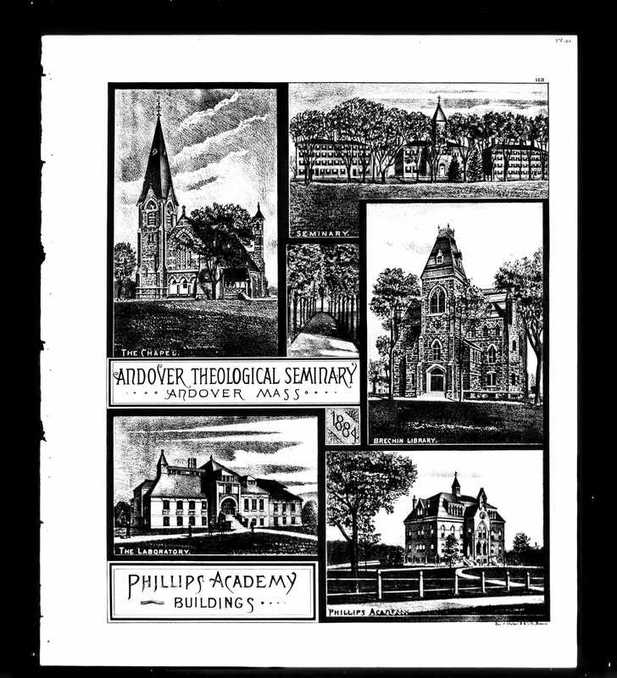

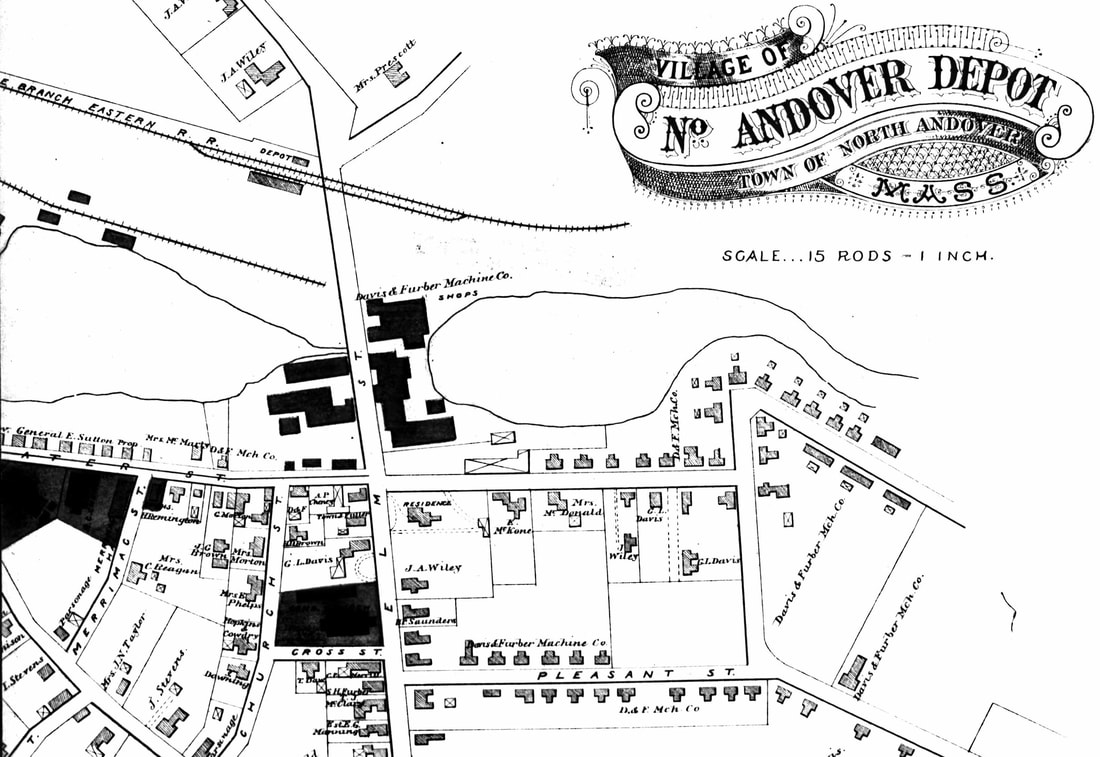

Below: A more expansive view of the facility when it was built. (A Long Read) Above: the South Parish Church, Andover, Massachusetts. The current church is the fourth meetinghouse built on the site. Photo by the author. Around the year 1800, a battle began over culture and tradition in the old town of Andover, setting the northern part of the town against the southern part. On the northern side was progressive, liberal enlightenment thinking that came to dominate the more educated classes of eastern Massachusetts in the nineteenth century; on the southern side were old New England traditions that were in danger of being lost. The split was arguably hastened by the much more significant industrialization of the North Parish by the 1840s, with large mills clustered around Cochichewick Brook and a growing area of worker housing, Machine Shop Village adjacent to newly-formed Lawrence; versus the less-industrialized South Parish. In many ways the conflict found in this one town, Andover, encapsulated the competing cultural trends of the first half of the nineteenth century of Massachusetts: Enlightenment versus Puritan; Urban versus Rural. These days, most people seem to be unaware of the somewhat tortured history that led to the separation of North Andover, which is actually the oldest part of the town, from Andover. Brief history of Andover’s parishes The town of Andover was founded in the early 1640s at the tail end of the original Puritan settlement that accompanied the Great Migration. See the Glossary. For many decades after original settlement, the town of Andover stood along the north-western frontier of settlement in Massachusetts, along with its then-near-twin on the northern bank of the Merrimack River, Haverhill. A few miles beyond the northern bank of the Merrimack was wild, forested country inhabited only by native Americans. The first settlement in Andover occurred at the present-day North Andover common, the oldest part of then-Andover. In addition to establishing a meetinghouse and hiring a minister from Harvard – the source of virtually all puritan ministers – a schoolmaster was appointed to teach reading, writing and arithmetic (required by Massachusetts law from 1642 onward). A common was laid out and house lots were provided nearby for convenience and for mutual protection against potential Indian raids. Farm lands were allocated to residents on the periphery of the town. After the original settlement, few houses were built on the common and all further residences were built closer to allocated farmland. Despite the original settlement of Andover in the 1640s near Cochichewick Brook, the population continuously shifted southward. In 1697, upon the death of Andover's second minister, the town agreed in principle to build another meetinghouse that was more convenient to more of the population. After a decade of dispute over proper location, the General Court of Massachusetts became involved, and a "South Parish" was "set off", meaning that, henceforth, residents in the larger, southern part of the town would be assessed separately in support of their own minister and meetinghouse. That first South Parish church was erected slightly to the east of the present-day South Church, while the North Parish built its own new meetinghouse on basically the same location as the previous North Parish meetinghouse. The two Andover parishes then co-existed uneventfully for a century. Such "setting off" was the ordinary course of things. The town of Haverhill, which at that time was enormous compared to Andover, had set off three additional meetinghouses and parishes by 1744 while remaining one town (with the exception of the creation of Methuen in 1725). Despite a history of harmony, however, starting around 1800, a number of social and economic currents ultimately drove the two Andover parishes apart, into near diametric opposition. After half a century of estrangement, they finally divorced in 1855, with the South Parish (plus its recent offshoot the West Parish) taking the name of Andover in exchange for a $500 payment; and the North Parish becoming the town of North Andover. Here is the story of that break-up. New England Congregationalism in the Age of Enlightenment The period following the American Revolution (and arguably all of the eighteenth century) was the Age of Enlightenment. Prominent thinkers, from Voltaire and Montesquieu in France, to David Hume and Adam Smith in Scotland, had shaped the Western intellectual landscape that hitherto had been dominated by theologians. Mankind grew confident in its ability to shape its own destiny, through rational thought and technology. According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “the expectation of the age [was] that philosophy – in the broad sense of the term, which includes the natural and social sciences – would dramatically improve human life.” In New England, Enlightenment thinking shone through the prism of the American Revolution. “Eighteenth century Rationalism under the influence of English philosophers like John Locke became the basis for new religious thought in the same way it had helped free America’s spirit of political independence. Locke defended individual liberty and equality and defended human rights. By 1805, Arminians had revamped Christian theology to conform with the principles of the Age of Rationalism.” From And Firm Thine Ancient Vow: The History Of North Parish Church of North Andover, 1645-1974, by Juliet Haines Mofford (1974). Who were these “Arminians”? In the context of the established congregationalist churches of Massachusetts, these were ministers and their followers who had rejected the harsh predestination of their puritan forbears, as taught by reformation leader John Calvin (hence Calvinism or Calvinist). Instead, they espoused the views of Jacobus Arminius. He was a Dutch reformation leader who had opposed the views of Calvin. We are not chosen to believe, he said (contrary to the Calvinist notion of “the elect”), but instead, all humans are given the power to believe in order then to be chosen by God *if* they chose to believe. Christ furthermore died to save all people, not just the elect, and in fact may not have been divine. (This led to the label “Unitarian” from critics, who wanted to uphold the Trinity of the godhead, Father, Son and Holy Spirit.) Some commentators viewed this shift as a natural consequence of the American revolution. “Most Arminian ministers were staunch Federalists and strong supporters of the politics of Washington and John Adams. Many ministers saw in Washington a symbol of national unity possible under the hand of God’s providence and guidance, and they said so in sermons.” (Again, quoting Moffard.) The Unitarians Begin to Dominate “The thoughtful men who represented the Liberals…were few in number at first and with few exceptions lived under the shadow of Beacon Hill or nearby.” (meaning they were your typical Boston rich liberal elites, I guess) (quoting The History of the Andover Theological Seminary, by Henry K. Rowe (1933)). However, by 1800, Boston’s Congregationalist churches had gone solidly Unitarian, with only two out of fourteen maintaining traditional Calvinist ministers. This led to the formation of Park Avenue Congregationalist Church, so-called Brimstone Corner, which reverberated with Calvinistic sermons about the utter depravity and damnation of man. The thunderbolt for the traditionalists, however, was the fall of Harvard to the Unitarians. Prior to 1800, Harvard college was essentially a training ground for all Massachusetts ministers. All students were a classical education deeply focused on reading of original texts in Greek, Latin, Hebrew and Aramaic, regardless of whether they went on to become ministers. The times they were a’ changing, however. “The tendency of the period was to introduce other studies in place of the older discipline, as science and modern literature became more popular in learned circles than Hebrew and Greek.” In short, in higher education, “Theology lost its position as queen of the sciences.” So, “when Reverend Henry Ware of Hingham was elected to the Hollis professorship of divinity at Harvard College in 1805, New England Congregationalism felt the shock, for it was well understood that Ware was really a Unitarian, and that at Cambridge his influence would be radical.” (All quoting Rowe). The Merrimack Valley is the epicenter of the Calvinist response – Andover and Newbury factions The strongest responses anywhere in Massachusetts to the fall of Harvard to the Unitarians seem to have come from Calvinist luminaries in Andover and in Newbury. “Dr. Eliphalet Pearson was disturbed gravely by the liberal trend at Harvard. Pearson was one of the outstanding men of the time in educational circles. He had been the first principal of Phillips Academy and had established its reputation, and after eight years he had been elected to a professorship at Harvard.” (Quoting Rowe.) Phillips Academy, located on a hill in Andover’s South Parish and chartered 1778, was in many ways just another typical “academy” found across that region at that time: a secondary school focused on advanced education for older boys, and sometimes girls, in order to further train them beyond the Three Rs of the schoolhouse –and, in the case of boys, prepare them for the rigors of Harvard. Governor Dummer’s Academy in the Byfield section of Newbury was the precedent for all of these academies of the lower Merrimack Valley, being the alma mater of Samuel Phillips, founder of Phillips Academy. Other similar academies could be found in Groton (now called Lawrence Academy, which for decades also educated girls), Haverhill (the “Haverhill Academy”, the first academy to accept girls, merged with Haverhill High School in 1841), and even in the North Parish of Andover (“Franklin Academy” which closed around 1845 – more on that below). However, from the early days, Phillips Academy did apparently stand out in terms of its academic rigor. “When [Pearson] failed to stem the tide of liberalism [at Harvard] in 1805, and then when Professor Webber was chosen president the next year, Pearson resigned his office and went back to Andover, convinced that something needed to be done to defend orthodoxy. The Academy, of which he was a trustee, cordially welcomed his return and gave him a year's rental of a new house nearby. Then he began to plan for the establishment of a theological institution which should maintain the doctrines of the fathers of New England against the threatening apostasies of the times.” (Quoting Rowe) Meanwhile, downriver in Newburyport, similarly minded leaders were meeting. Technically they were “Hopkinsonians” with slightly less Calvanistic views than Pearson and his cohorts on Andover hill. “Their leader was Dr. Samuel Spring, minister at Newburyport. He had been a pupil of both Hopkins and Bellamy, and had been a recognized leader in eastern Massachusetts for forty years. Leonard Woods, a young minister at West Newbury, was his close friend. Through Spring and Woods three laymen were aroused to an interest in theological education. These were William Bartlet [one t], a successful merchant of Newburyport, Moses Brown of the same town, and John Norris of Salem. They were all men of wealth, and though not all church members they were willing to use their money for religious purposes, and they soon agreed to support the plans for a theological school at West Newbury.” Why was the orthodox response to the Unitarians focused in the lower Merrimack Valley? My theory is that the region had the goldilocks location of not-too-much, not-too-little: on the one hand, it was still part of the original Puritan heartland settled by the Great Migration, and therefore of enough significance to have cultural sway over much of New England, unlike the frontier areas of New Hampshire and western Massachusetts that were still being cleared; yet, on the other hand, it was peripheral enough not to have fallen completely under the cosmopolitan influence of turn-of-the-nineteenth-century Boston, which was increasingly becoming a global port through which flowed the wealth of international trade via world-renowned Yankee merchant ships. Below: Andover Theological Seminary 1884 Founding of the Andover Theological Seminary After significant negotiation, the Pearson wing and the Woods wing agreed to form a theological seminary in Andover next to the site of Phillips Academy, sharing the same Board of Trustees as the academy. Because the two factions could not agree on the wording of their creeds, there were two sets of founding documents for the Andover Theological Seminary, one for the orthodox Calvinists and one for the Hopkinsonians. They were however unified in their antipathy toward Unitarians. On the orthodox side, it was provided that every professor must at the time of his inauguration solemnly promise to maintain and inculcate the Christian faith as summarily expressed in the Shorter Catechism [a standard statement of belief of early puritans] "in opposition not only to Atheists and Infidels, but to Jews, Mahommetans [i.e. Muslims], Arians, Pelagians, Antinomians, Arminians, Socinians, Unitarians, and Universalists, and to all other heresies and errors, ancient or modern, which may be opposed to the Gospel of Christ, or hazardous to the souls of men." Furthermore, every professor must repeat this declaration in the presence of the Trustees once in five years. Getting the Hopkinsonians on board was important because of the wealth they brought. The main building was named Bartlet Hall in gratitude for the gift of their main benefactor (it exists today on the campus of Phillips Academy and has been renamed Pearson Hall). The Hopkinsonians were thus allowed to have Associate Statutes that existed alongside the institution’s charter documents, and every occupant of a chair endowed by the Hopkinsonians “should be a Hopkinsonian.” “The establishment of the Seminary was a significant event in American church history. The union of the two theological groups of conservatives in the Seminary proved an effective counterpoise to the Unitarian trend in Congregational circles. Naturally the Liberals were not pleased. The Harvard attitude was not friendly. Woods reported to Farrar in 1807 that there was ‘loud murmuring and reproach and imprecation.’” (Rowe) “ANDOVER [Theological Seminary] was founded for the distinct purpose of preparing men for the parish ministry. At that time the prestige of the Trinitarian Congregationalists was at stake. The Unitarians had the advantage of Harvard instruction and the Harvard reputation. Unless the Trinitarians could establish a theological school that would attract young men of ability, and year after year could supply the Congregational churches with orthodox leaders who were able to measure swords successfully in doctrinal controversy when need arose, they would be worsted in the competition of the two theological parties.” It should be noted that, “in a legal sense the new Seminary at Andover was the theological institution in Phillips Academy, but it was so distinct in faculty, buildings, and funds as to be actually a separate school.” (Rowe) “It soon eclipsed Phillips Academy in endowment, buildings, and reputation. A few years after its founding, it included two large brick dormitories--the present Foxcroft and Bartlet Halls—with a chapel and recitation building...In addition, a number of homes had been constructed for the Seminary professors, the most im pressive being the present Phelps, Pease, and Stuart houses. By contrast, Phillips Academy had one wooden classroom building and a modest house for its principal.” (From Youth from Every Quarter: A Bicentennial History of Phillips Academy, Andover by Frederick S. Allis, Jr. (1979)) In sum, the essential institution for defending orthodox congregationalism was founded on a hilltop in the southern part of Andover, which some in the North Parish of Andover then called “Brimstone Hill.” The Seminary – the first school in America for training ministers that was not part of a college – was technically in the South Parish, but had its own independent congregationalist church. The Seminary exercised significant sway over the philosophy of the nearby South Parish church, and then the West Parish church, which was set off from the South Parish in 1824. Both were avowedly Trinitarian (and thus, at the time, Anti-Unitarian). They are still Trinitarian, to the extent such distinctions are relevant in modern society. Meanwhile, the North Parish of Andover was going in a very different direction As you might have guessed, the members of the North Parish generally considered themselves more forward thinking and enlightened. The South Parish handbook of 1859 went out of its way to label an early North Parish minister, Reverend William Symmes, who was ordained in 1758 and died in 1808, as an “Arminian” although such label is debatable. Another historian of the region, Sarah Loring Bailey in her 1880 history of Andover, called Symmes “the last of the old-time ministers.” It is definitely true that when a new minister was sought for Andover’s North Parish in 1809, being too Calvinist led to a rejection. “When, after the death of Dr. Symmes, the parish came together to ordain the minister whom they had called, the Rev. Samuel Gay, it proved that the views of Christian doctrine which he expressed were not satisfactory to all the officers of the church and parish, being more rigidly Calvinistic than they approved. The ordination services were, therefore, broken off.” (Quoting Bailey) Instead, they hired Reverend Bailey Loring who was ordained on September 19, 1810, age twenty-three. Interestingly, he was a graduate not of Harvard but of Brown. Of the four colonial era colleges in New England, Brown was an outlier in that, from its inception, it allowed different religious views (although, having been founded by Baptists expelled from Massachusetts, it was required until 1950 to have a Baptist minister as its president). In my research of the various meetinghouses of the lower Merrimack Valley going back to the 1630s, I have never come across a minister educated at Brown, although two were educated at Yale and one at Dartmouth (other congregationalist stalwarts). Dozens if not hundreds of ministers in Massachusetts prior to 1800 were educated to Harvard. “Mr. Loring was not a Calvinist. His theological education had been under the Arminian school of belief. But, like his predecessors, he was catholic [meaning universal not Roman Catholic] in his sympathies, and maintained throughout his ministry friendly relations with his brethren of various creeds. He continued to exchange pulpits with those of similar tolerant principles, even after the partition walls had been built up between the two divisions of the Congregational order, and when this breaking through was censured by the more dogmatic of both parties.” (Quoting Bailey) He did, however, establish a new covenant between members, one of distinctly Unitarian beliefs. Some supporters of the North Parish side of the story saw a conspiracy against him coming out of the Seminary and the South Parish. Ms. Moffard notes in her 1974 history of the North Parish church that Loring was rejected from the Andover Seminary for incompatible beliefs, and this fact “weighed in Mr. Loring’s favor” when he was ordained by the North Parish. “Bailey Loring was their man, an unmistakable and irrepressible Arminian who was undaunted by the proximity of the new seminary in South Parish.” (quoting Moffard) “The schism began, possibly as early as 1820, when certain members felt that Mr. Loring and North Parish were not satisfying their soul yearnings…they held the belief, not only in Jesus of Bethlehem, a historical teacher [the classic Unitarian view which, by the way, in my book is no longer Christian per se], but in Jesus the Christ, Lord and Savior…Students from the Seminary were often present to lead them in worship.” (Moffard) Eventually, a Trinitarian faction was able to form in North Parish, apparently aided by the Theological Seminary. Their situation was greatly aided by the 1833 disestablishment of the Congregational churches in Massachusetts, which meant that, henceforth, financial support could not come from the parish poll tax; rather, churches had to be dependent on their members, who could live wherever they wanted. On July 24, 1834, the Trinitarian Calvinistic Church was formally organized. On September 3, 1834 the new building was declared. It could be viewed as a mission church from the South Parish: of its members, only one male member was a defector from the North Parish, while 14 came up from the South Parish. This church changed its name to Trinitarian Congregational Church in 1841, and bears that name to this day. The Unitarians in North Parish engaged in no such missionizing, and for the entire 19th century, Andover’s South and West Parishes had no Unitarian church, presumably being under the sway of the Theological Seminary. The existing Unitarian-Universalist church in Andover moved there from Lawrence in 1964. Below: Interior of North Andover’s Trinitarian Congregational Church, built 1865 by the same architect as the 1861 Andover South Parish Church (source: church website) The Cultural Differences Between North Parish and South Parish Illustrated by a Comparison of Academies Pages could be written about the strict, cold demeanor of Phillips Academy and the Andover Theological Seminary. The following gives a flavor of life as a student at the Theological Seminary. Life at the Academy was not that much different apparently. “For exercise the students blasted and cleared away rocks from the Missionary Field back of the buildings, worked on the campus grounds, and rambled about the vicinity. Two students, one of whom became a well-known college professor, used to race each other around a three-mile triangle on winter mornings before sunrise to give tone to breakfast and the day's work. Professor Park, when a student at Andover, arose at 4.30 and walked with another student over Indian Ridge or through Carlton's Woods, practising elocutionary exercises in order to develop his oratorical powers.” (Rowe) The author notes rather dryly “The students do not seem to have been miserable, perhaps because they were seldom idle.” Here is a letter from one Andover student in 1819: “That you may know how much a slave a man may be at Andover, if he will follow the rules adopted by the majority, I will give the order of the day. By rising at the six o'clock bell he will hardly find time to set his room in order, and attend to his private devotions, before the bell at seven calls him to prayer in the chapel. From the chapel he must go immediately to the hall and by the time breakfast is ended, it is eight o'clock, when study hours commence and continue till twelve. Study hours again from half past one to three. Then recitation, prayer, and supper, makes it six in the afternoon. Study hours again from seven to nine leave just time enough for evening devotion before sleep.” Meanwhile, the North Parish had its own academy, the so-called Franklin Academy. It can hardly be more different than Phillips Academy, yet in its heyday it seems to have attracted students from as far and wide as Phillips Academy. “In 1799, Mr. Jonathan Stevens gave land on the hill north of the [North] meeting-house. Subscriptions were made by some of the principal citizens. The academy also received a fund of a little more than eight hundred and seventy-five dollars from the division of the proprietors' money [each of Andover and Haverhill and successor towns such as Methuen had rights obtained from the original settlers, the so-called Proprietors, who had paid money for the deeds from the Indians; by the eighteenth century, it was a separate fund that was slowly depleted as the last of the proprietor land was sold off]. The academy was built in 1799. It had been provided that the school should be for both sexes, and it was the first incorporated academy in the State where girls were admitted. The academy was built with two rooms of equal size, — the north room for the male department, the south room for the female department. A preceptor and preceptress had charge respectively of the two departments.” “The school was incorporated in 1801 as the North Parish Free School, and in 1803, by act of the General Court, the name was changed to Franklin Academy. This school, though now discontinued, had a flourishing life of more than fifty years, and numbered among its members students from more than a hundred different towns, a dozen States, and several foreign countries…”(in other words, on par with Phillips Academy of the time.) “Two manuscript records have been found, one containing the names of the male students from 1800 to 1802, and from 1811 to 1834, the other the names of the female students from 1801 to 1821. The names of the preceptors are nowhere found recorded, and the recollections of the pupils and residents of the town in regard to them are indistinct and often conflicting. The following are such facts as the means of information supply: The first Preceptor was Mr. [presumably the Rev. Micah] Stone, of Reading, a graduate of Harvard College 1790, tutor 1796, student of theology with Rev, Jonathan French, Andover, settled 1801 at Brookfield. Mr. James Flint (Rev. Dr. Flint, of Salem) was Preceptor, 1800-1811.” The student experience at Franklin Academy contrasts markedly with the Calvinistic south parish and Phillips Academy: “The reminiscences of the few who yet remain of the early students of Franklin Academy, are of delightful days. The notions of propriety in the North Parish were then much relaxed from the rigidity of Puritan customs, and many social recreations were permitted to the young folks. These festivities the elders directed and shared.” The Franklin Academy ultimately went out of business, it was said, because North Parish – soon to be North Andover – started providing decent town-led secondary education in the form of a High School. This was also the fate of Haverhill Academy, another early academy. It is not surprising that in liberal North Parish, universal secondary education should become provided for by the town and not by private means. Below: North Andover Depot, 1884 showing Davis & Furber facilities on the Cochichewick Brook. Note the Trinitarian Congregational Church at Cross & Elm The Split The actual split into two towns did not happen until 1855, when the matter was put to a vote. South Parish paid North Parish $500 to use the name Andover, despite North Parish being the original part of Andover. By the time of the split, North Andover had become significantly industrial. Four significant industrial concerns clustered around Cochichewick Brook: North Andover Mills, Scholfield Mills, Sutton Mills and Davis and Furber Machine Company. This area of North Parish was in some ways an appendage of Lawrence. There was even discussion of the entire North Parish becoming part of Lawrence, then a booming industrial city full of promise and on the up-and-up (and in 1877 a small section did become part of Lawrence). It is indicative that, whereas the Machine Shop in North Andover was already connected to Lawrence by public street trolley in 1868, there wasn’t a trolley to Andover until the 1890s, the peak of trolley construction when trolleys ran to every neighboring town. (Source: Maurice Dorgan’s Concise History of Lawrence, 1918). “Though the south village of Andover remained unchanged, the industries of North Andover and the mills of Lawrence were so near that her citizens could not remain oblivious to the changes that were taking place. With a rapidly increasing population, New England was sending her sons to the West to be pioneers like their colonial ancestors, and home mission societies were organizing to take care of their religious needs. [See my review of Yankee Exodus.] The application of steam to railway and river travel facilitated the movement of the population, and people became less provincial as their contacts widened.” Supposedly, the split was led by members of the South Parish. They have wanted to keep their relatively rural, traditional idyll untainted by the newfangled ideas and newfangled megaindustry that typified the North Parish. A description of Andover Hill written in 1856 by a student reflects the desire to maintain the rural idyll despite the encroachment of industry and change: "To the north the eye can travel up to the blue hills of New Hampshire, and only three miles distant stand and smoke the mammoth factories of the city of Lawrence. The whole scenery about is dotted with sequestered villages and snow-white farmhouses. Lowell, Salem, Haverhill, and Boston, are next-door neighbors. On the south is a hedge of railroad; on the east we can almost hear the roaring of the ocean; on the north flows the devious but busy Merrimac; while the west, to say nothing of its home associations, gives us a never-to-be-forgotten sunset. Thus environed, overarched by a deep blue sky, and standing upon ground whose beauty pen and paper cannot paint, Andover is the spot for a seminary. . . . Nearly every house looks like a countryseat, and even the old edifices, which were raised, I suppose, in the last century, have an air of neatness about them, being clothed in the purest white. It is a very wealthy place; but the wealth of the Seminary astonishes me. Nearly every house within a quarter of a mile is owned by the Trustees." Legacy of the Andover Theological Seminary By 1908 when the Andover Theological Seminary departed from Brimstone Hill in south Andover for Cambridge, leaving Phillips Academy to fend for itself again, the world was completely different from when it was founded a century earlier. Both forms of congregationalist religion were dissipated, Unitarian and Trinitarian, as competing protestant denominations planted their roots in New England; and then as Boston elites started defect en masse to the Episcopalians, perhaps conflating their Yankee roots with Englishness and forgetting that the Anglican Church had been the scourge of the puritans. The Seminary itself suffered scorn and mockery in the Boston papers for engaging in a sort of theological purity test for Professors in the 1880s. Its heyday was the period from 1808 to the Civil War. When it merged into the Harvard Divinity School (ironically) it only had three students. Yet it left a gigantic legacy on the intellectual landscape of America, because of the tendency of traditional Congregationalists who migrated out of the puritan heartlands of New England (see my entry on the Yankee Exodus) to establish colleges…and their desire to have intellectually rigorous Andover Seminary men as presidents of those colleges. “It is impressive to call the roll of colleges that invited Andover [Seminary] men to be their presidents. In New England they include Bowdoin and Dartmouth, Middlebury and the University of Vermont in the northern tier of states; Amherst, Smith and Brown in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. In New York were Hamilton, Union, and Vassar. Five were in Ohio: Antioch, Marietta, Oberlin, Western Reserve, and Ohio Female College. Moving steadily westward one finds Andover alumni at Wabash, Indiana, Illinois and Knox in Illinois, Drury in Missouri, Washburn in Kansas, Colorado among the Rockies, and Pomona in California. In a more northerly latitude are Adrian and Olivet in Michigan, Beloit in Wisconsin, Iowa College in Iowa, and Fargo in North Dakota. Howard University in Washington, D. C, Atlanta in Georgia, Rollins in Florida, Fisk in Tennessee, and state colleges in Alabama and Tennessee, gave wide representation to Andover in the South. For good measure the universities of Wisconsin and Kansas should be added. And overseas were Robert College in Constantinople and the Syrian Protestant College at Beirut [later the American University of Beirut].” (quoting Rowe) North Parish Unitarian Church, North Andover, Mass. Photo Source: Wikipedia. Present structure erected 1834.

Daniel Saunders..."founder" of Lawrence, Mass., rube [?] and fifth great uncle by marriage [!]12/17/2017 Above: My home until age 2 1/2, Saunders Street, Lawrence, Mass., circa 1973