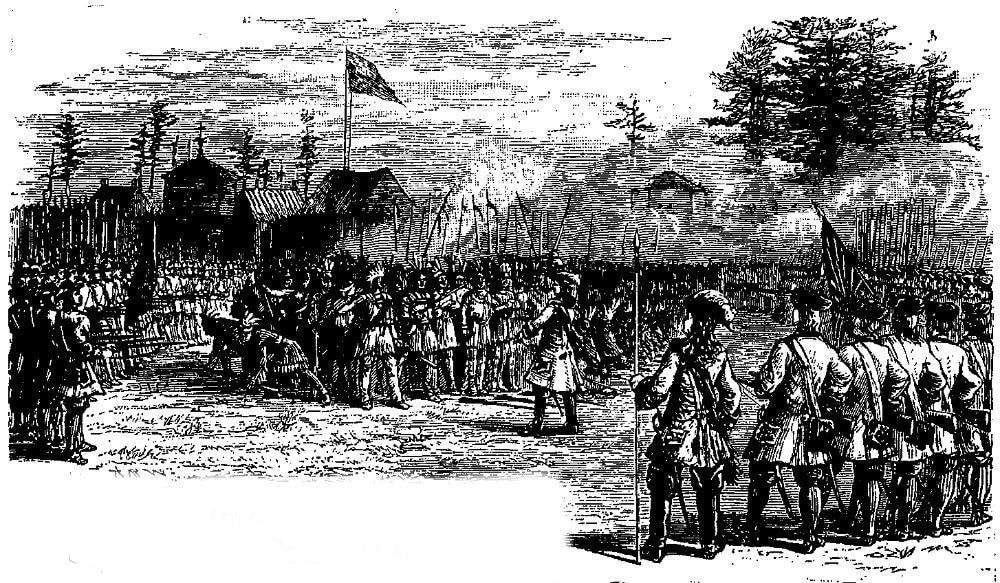

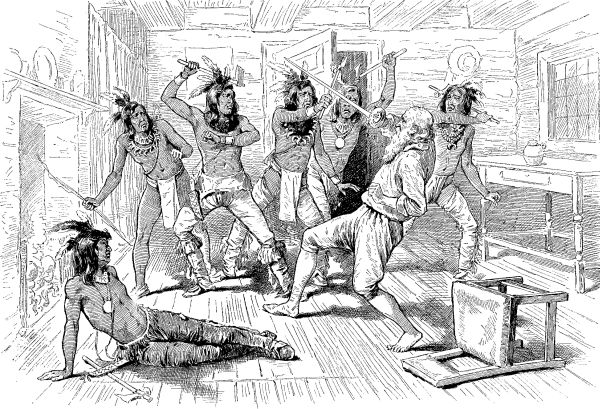

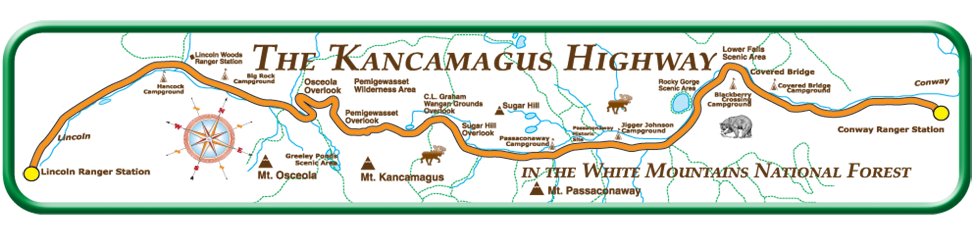

The Assassination of Major Richard Waldron by Kancamagus, last Sachem of the Pennacook Indians1/20/2018 Background The broad strokes of the story are already intriguing: First, we have an imperious colonial captain, Richard Waldron (or Walderne) who rules his frontier trading post at Cocheco (in modern-day Dover, New Hampshire) as his own personal fief. Although the towns of Hampton, Portsmouth, Exeter and Dover have temporarily come under Massachusetts jurisdiction (see Old Norfolk in the Glossary), this is an area where some settlers have claims to great tracts of land, Waldron being one of them. He gains notoriety for his treatment of Quaker missionaries to this area in 1662. He forces them to march eighty miles through the area in the dead of winter, having them publicly whipped every ten miles. Our chronologer of the area, John Greenleaf Whittier, covered it in one of his poems: Bared to the waist, for the north wind's grip And keener sting of the constable's whip, The blood that followed each hissing blow Froze as it sprinkled the winter snow. Waldron is also known for sharp practices ripping off his native American trading partners. For example, when they catch him putting his hand on the scales, he tells them his fist weights exactly a pound so they are not being deceived. The Indians nevertheless return to his post because of its proximity and convenience, and his supply of useful wares. Then we have Kancamagus, grandson of Passaconnway, great sachem of the Pennacooks. In 1684, he appears on the scene, writing a letter to the governor, in which he calls himself John Hogkins, asking for protection against the Mohawks, ancient enemies of the New England indians. Whether the governor provided protection is not known. In any case, Kancamagus a.k.a. John Hogkins forswears the peaceable ways of Wonalancet, his uncle. In 1689, he vows to stand up to the English. Because there are barely any Pennacooks left to lead, he leads an alliance with the natives of the Androscoggin River valley. Waldron in King Philip's War In the native uprising of 1675 known as King Philip's War, Major Waldron signed a peace treaty with the local sachem, the hapless Wonalencet. Below: The signature of Richard Walderne a.k.a. Waldron As a gesture of peace after the treaty, in September 1676, Waldron invites his Pennacook trading partners into a playing a "game" with the company of men he commands. However, it's actually a trap. He proposes a mock "battle", in which the Indians are given a canon to use, with powder but no shot. While they are awed and distracted by this device, the 400 natives are surrounded by four companies of colonial men, and disarmed. The Indians are then sorted, with the individuals known to be peaceable -- such as Christian converts living in the Praying Towns along the Merrimack -- allowed to go free. The remaining two hundred Indians are imprisoned and sent to Boston for trial. Seven are hanged for treason and the remainder are sold into slavery in Barbados. Some accounts say Wonalencet himself was transported to Barbados, but managed to make his way back home. In any case, the authority of Wonalancet was shattered, and eventually his nephew Kancamagus took up the mantle of "sachem" of the Pennacooks. Below: A nineteenth century illustration of the "Deceit of Captain Waldron" wherein the Indians are surrounded and captured. According to a 1989 commemoration of the 300th Anniversary of the "Cocheco Massacre", the event took place in a field where the parking lot for Aubuchon Hardware currently is. Waldron in King William's War: The "Crossing Out of the Account" Fast-forward thirteen years. There is a new war between the English and the natives, known as King William's War. (See the Glossary.) Captain Richard Waldron is now Major Richard Waldron. He is an old man of means and status. For example, he had been the second president of the Royal Council of New Hampshire, a governing body created by the separation of Old Norfolk from Massachusetts. His trading post, on the Cocheco River, is comprised of five garrison houses. He is warned that a large band of natives have assembled at Pennacook (modern-day Concord, New Hampshire), with the intent of attacking him. They are led by Kancamagus, who vows to avenge the false hospitality and deception that led to the destruction of his tribe. Below: A surviving garrison house from the 1670s, photographed in the mid-nineteenth century When warned about the threat, Major Waldron is dismissive. He is supposed to have said "let them go plant their pumpkins" --- which I guess means "go about your business and don't worry about it". On the night of June 27, 1689, according to the Indians' plan of attack, two squaws requested permission to lodge in each garrison at Cocheco. This was apparently a common practice, to grant lodging to local Indians known to the colonists. "No fear was discovered among the English, and the squaws were admitted. One of those admitted into Waldron's garrison, reflecting, perhaps, on the ingratitude she was about to be guilty of, thought to warn the Major of his danger. She pretended to be ill, and as she lay on the floor would turn herself from side to side, as though to ease herself of pain that she pretended to have. While in this exercise she began to sing and repeat the following verse: O Major Waldon, You great Sagamore, O what will you do, Indians at your door! No alarm was taken at this, and the doors were opened [by the native women] according to their plan, and the enemy rushed in with great fury. They found the Major's room as he leaped out of bed, but with his sword he drove them through two or three rooms, and as he turned to get some other arms, he fell stunned by a blow with the hatchet. They led him into his hall and seated him on a table in a great chair, and then began to cut his flesh in a shocking manner. Some in turns gashed his naked breast, saying, "I cross out my account." [meaning, our account is now settled.] Then, cutting a joint from a finger, would say, " Will your fist weigh a pound now'!'' His nose and ears were then cut off and forced into his mouth. He soon fainted, and fell from his seat, and one held his own sword under him, which passed through his body, and he expired. The family were forced to provide them a supper while they were murdering the Major.” (From: The History of the Great Indian War of 1675 and 1676, Commonly Called King Philips War by Thomas Church (Hartford, 1851)(ed. Samuel G. Drake)). Below: A nineteenth century depiction of the assassination of Major Waldron. Kancamagus disappeared into the wilderness of the Androscoggin valley, along with twenty-nine captives to be held for ransom. Vengeance had been served. And so ends the tale of Major Waldron. Or does it? Interpreting and Analyzing the Story The "crossing out of the account" is a compelling narrative of deceit and retaliation. If you go further into the details, though, it is also important for illustrating how personal these battles (to the death) between English and Indians were. Generally speaking, the attackers were not anonymous natives from afar. Everyone was known to everyone. And whole families were involved, with both sides capturing the others' wives and children to use as bargaining chips. This led to cycles of violence and retribution. For example, Captain Charles Frost of Kittery, who commanded one of the four companies that captured the indians in Waldron's deceit in 1676, was hunted down and assassinated in Eliot, Maine on July 4, 1697. Frost himself had been inspired to treat the natives with hostility by an attack on his family in 1650, in which his mother and sister were killed. Perhaps the most famous case of a cycle of personal vengeance was Jeremy Moulton's. At the age of four, his parents were killed and he was captured in the devastating 1692 raid on York, Maine, probably the most destructive Indian raid in New England. Fast forward to 1724, and he was leading the successful attack on Father Sebastian Rale, the French Jesuit missionary who instigated the attacks, killing him and many Indians at present-day Norridgewock, Maine. In other cases, the connection was one of mutual mercy instead of mutual retribution. According to Cotton Mather’s Magnalia Christi Americana [a.k.a. Ecclesiastical History of New England], Elizabeth Heard was a witness to Waldron’s deceit in 1676, and there she sheltered a young native Abenaki boy from death. On the night of the Cocheco Massacre, an Indian pointed his musket at her, but suddenly spared her life because of the recognition of who she was. Her house, defended by William Wentworth because her husband had recently died, was not invaded. Among the twenty nine captives taken during the Cocheco Massacre were Sarah Gerrish, the 7 year old granddaughter of Major Waldron, and Esther Lee, daughter of Richard Waldron along with her (presumably infant) child. Lee's husband was killed in the raid, and her infant child did not survive captivity. She and the little girl Gerrish her niece were both ultimately returned to Dover in a prisoner exchange. The use of family members as captives ultimately led to the downfall of Kancamagus. In September 1690, an English force under the command of Capt. Benjamin Church located and attacked Kancamagus’s village on the Androscoggin River. Somehow, Kancamagus was able to escape the attack, but his family wasn’t so lucky. His sister was slain and his brother-in-law, wife and children were taken captive, although his brother-in-law was later able to escape. Captain Church took the captives to Wells, Maine, where they were used to try to lure Kancamagus to the peace table. In response to the attack on his village and the capture of his family, Kancamagus launched an attack on Church at Casco, Maine, on Sept. 21. After a great deal of hard fighting, which resulted in the death of seven of Church’s men and 24 wounded, Kancamagus was beaten back. With the English still holding his family hostage, Kancamagus was forced to make peace with the English at Wells. Following this agreement of peace, Kanacamagus was reunited with his family. After 1692, little is written about Kancamagus. It’s possible that once he recovered his family, he continued to fight alongside other Abenaki people, although that is purely speculation. His name lives on in the scenic road well-loved by leaf peepers. However, I'm sure that, as tourists drive the Kancamagus Highway, they have scant knowledge of the story of his life. Above: map of the Kancamagus Highway. Source: http://kancamagushighway.info/

3 Comments

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed