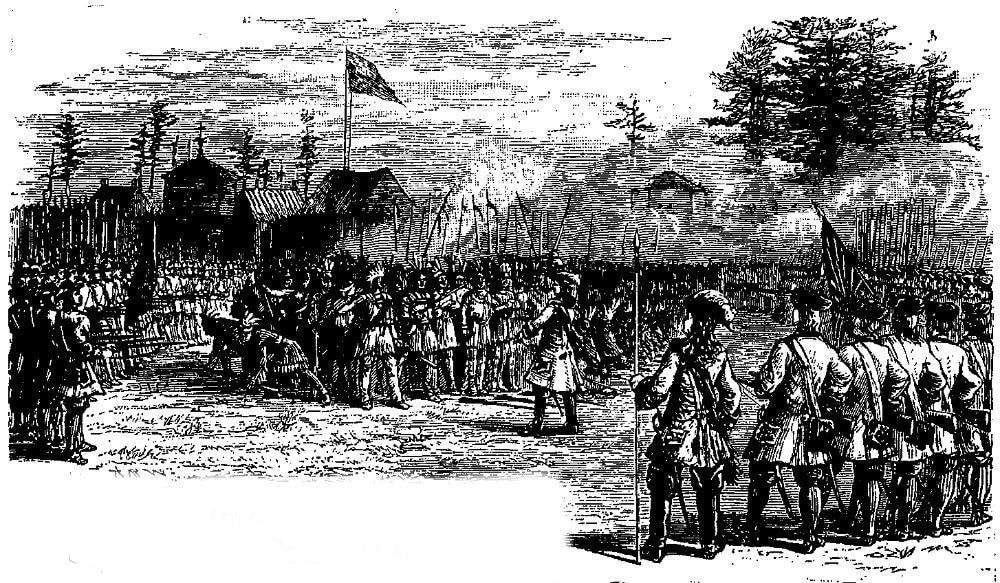

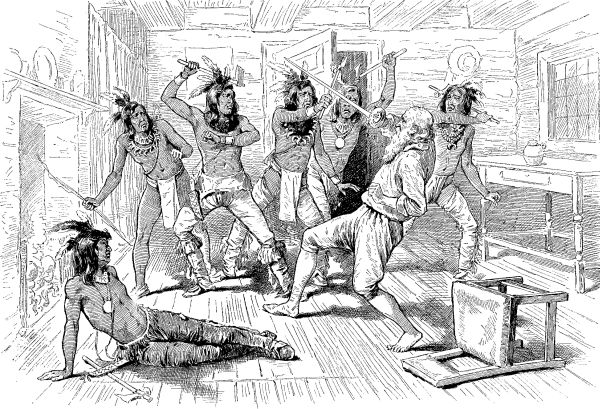

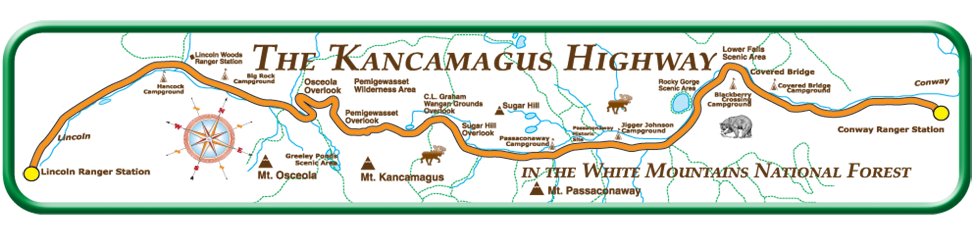

The Assassination of Major Richard Waldron by Kancamagus, last Sachem of the Pennacook Indians1/20/2018 Background The broad strokes of the story are already intriguing: First, we have an imperious colonial captain, Richard Waldron (or Walderne) who rules his frontier trading post at Cocheco (in modern-day Dover, New Hampshire) as his own personal fief. Although the towns of Hampton, Portsmouth, Exeter and Dover have temporarily come under Massachusetts jurisdiction (see Old Norfolk in the Glossary), this is an area where some settlers have claims to great tracts of land, Waldron being one of them. He gains notoriety for his treatment of Quaker missionaries to this area in 1662. He forces them to march eighty miles through the area in the dead of winter, having them publicly whipped every ten miles. Our chronologer of the area, John Greenleaf Whittier, covered it in one of his poems: Bared to the waist, for the north wind's grip And keener sting of the constable's whip, The blood that followed each hissing blow Froze as it sprinkled the winter snow. Waldron is also known for sharp practices ripping off his native American trading partners. For example, when they catch him putting his hand on the scales, he tells them his fist weights exactly a pound so they are not being deceived. The Indians nevertheless return to his post because of its proximity and convenience, and his supply of useful wares. Then we have Kancamagus, grandson of Passaconnway, great sachem of the Pennacooks. In 1684, he appears on the scene, writing a letter to the governor, in which he calls himself John Hogkins, asking for protection against the Mohawks, ancient enemies of the New England indians. Whether the governor provided protection is not known. In any case, Kancamagus a.k.a. John Hogkins forswears the peaceable ways of Wonalancet, his uncle. In 1689, he vows to stand up to the English. Because there are barely any Pennacooks left to lead, he leads an alliance with the natives of the Androscoggin River valley. Waldron in King Philip's War In the native uprising of 1675 known as King Philip's War, Major Waldron signed a peace treaty with the local sachem, the hapless Wonalencet. Below: The signature of Richard Walderne a.k.a. Waldron As a gesture of peace after the treaty, in September 1676, Waldron invites his Pennacook trading partners into a playing a "game" with the company of men he commands. However, it's actually a trap. He proposes a mock "battle", in which the Indians are given a canon to use, with powder but no shot. While they are awed and distracted by this device, the 400 natives are surrounded by four companies of colonial men, and disarmed. The Indians are then sorted, with the individuals known to be peaceable -- such as Christian converts living in the Praying Towns along the Merrimack -- allowed to go free. The remaining two hundred Indians are imprisoned and sent to Boston for trial. Seven are hanged for treason and the remainder are sold into slavery in Barbados. Some accounts say Wonalencet himself was transported to Barbados, but managed to make his way back home. In any case, the authority of Wonalancet was shattered, and eventually his nephew Kancamagus took up the mantle of "sachem" of the Pennacooks. Below: A nineteenth century illustration of the "Deceit of Captain Waldron" wherein the Indians are surrounded and captured. According to a 1989 commemoration of the 300th Anniversary of the "Cocheco Massacre", the event took place in a field where the parking lot for Aubuchon Hardware currently is. Waldron in King William's War: The "Crossing Out of the Account" Fast-forward thirteen years. There is a new war between the English and the natives, known as King William's War. (See the Glossary.) Captain Richard Waldron is now Major Richard Waldron. He is an old man of means and status. For example, he had been the second president of the Royal Council of New Hampshire, a governing body created by the separation of Old Norfolk from Massachusetts. His trading post, on the Cocheco River, is comprised of five garrison houses. He is warned that a large band of natives have assembled at Pennacook (modern-day Concord, New Hampshire), with the intent of attacking him. They are led by Kancamagus, who vows to avenge the false hospitality and deception that led to the destruction of his tribe. Below: A surviving garrison house from the 1670s, photographed in the mid-nineteenth century When warned about the threat, Major Waldron is dismissive. He is supposed to have said "let them go plant their pumpkins" --- which I guess means "go about your business and don't worry about it". On the night of June 27, 1689, according to the Indians' plan of attack, two squaws requested permission to lodge in each garrison at Cocheco. This was apparently a common practice, to grant lodging to local Indians known to the colonists. "No fear was discovered among the English, and the squaws were admitted. One of those admitted into Waldron's garrison, reflecting, perhaps, on the ingratitude she was about to be guilty of, thought to warn the Major of his danger. She pretended to be ill, and as she lay on the floor would turn herself from side to side, as though to ease herself of pain that she pretended to have. While in this exercise she began to sing and repeat the following verse: O Major Waldon, You great Sagamore, O what will you do, Indians at your door! No alarm was taken at this, and the doors were opened [by the native women] according to their plan, and the enemy rushed in with great fury. They found the Major's room as he leaped out of bed, but with his sword he drove them through two or three rooms, and as he turned to get some other arms, he fell stunned by a blow with the hatchet. They led him into his hall and seated him on a table in a great chair, and then began to cut his flesh in a shocking manner. Some in turns gashed his naked breast, saying, "I cross out my account." [meaning, our account is now settled.] Then, cutting a joint from a finger, would say, " Will your fist weigh a pound now'!'' His nose and ears were then cut off and forced into his mouth. He soon fainted, and fell from his seat, and one held his own sword under him, which passed through his body, and he expired. The family were forced to provide them a supper while they were murdering the Major.” (From: The History of the Great Indian War of 1675 and 1676, Commonly Called King Philips War by Thomas Church (Hartford, 1851)(ed. Samuel G. Drake)). Below: A nineteenth century depiction of the assassination of Major Waldron. Kancamagus disappeared into the wilderness of the Androscoggin valley, along with twenty-nine captives to be held for ransom. Vengeance had been served. And so ends the tale of Major Waldron. Or does it? Interpreting and Analyzing the Story The "crossing out of the account" is a compelling narrative of deceit and retaliation. If you go further into the details, though, it is also important for illustrating how personal these battles (to the death) between English and Indians were. Generally speaking, the attackers were not anonymous natives from afar. Everyone was known to everyone. And whole families were involved, with both sides capturing the others' wives and children to use as bargaining chips. This led to cycles of violence and retribution. For example, Captain Charles Frost of Kittery, who commanded one of the four companies that captured the indians in Waldron's deceit in 1676, was hunted down and assassinated in Eliot, Maine on July 4, 1697. Frost himself had been inspired to treat the natives with hostility by an attack on his family in 1650, in which his mother and sister were killed. Perhaps the most famous case of a cycle of personal vengeance was Jeremy Moulton's. At the age of four, his parents were killed and he was captured in the devastating 1692 raid on York, Maine, probably the most destructive Indian raid in New England. Fast forward to 1724, and he was leading the successful attack on Father Sebastian Rale, the French Jesuit missionary who instigated the attacks, killing him and many Indians at present-day Norridgewock, Maine. In other cases, the connection was one of mutual mercy instead of mutual retribution. According to Cotton Mather’s Magnalia Christi Americana [a.k.a. Ecclesiastical History of New England], Elizabeth Heard was a witness to Waldron’s deceit in 1676, and there she sheltered a young native Abenaki boy from death. On the night of the Cocheco Massacre, an Indian pointed his musket at her, but suddenly spared her life because of the recognition of who she was. Her house, defended by William Wentworth because her husband had recently died, was not invaded. Among the twenty nine captives taken during the Cocheco Massacre were Sarah Gerrish, the 7 year old granddaughter of Major Waldron, and Esther Lee, daughter of Richard Waldron along with her (presumably infant) child. Lee's husband was killed in the raid, and her infant child did not survive captivity. She and the little girl Gerrish her niece were both ultimately returned to Dover in a prisoner exchange. The use of family members as captives ultimately led to the downfall of Kancamagus. In September 1690, an English force under the command of Capt. Benjamin Church located and attacked Kancamagus’s village on the Androscoggin River. Somehow, Kancamagus was able to escape the attack, but his family wasn’t so lucky. His sister was slain and his brother-in-law, wife and children were taken captive, although his brother-in-law was later able to escape. Captain Church took the captives to Wells, Maine, where they were used to try to lure Kancamagus to the peace table. In response to the attack on his village and the capture of his family, Kancamagus launched an attack on Church at Casco, Maine, on Sept. 21. After a great deal of hard fighting, which resulted in the death of seven of Church’s men and 24 wounded, Kancamagus was beaten back. With the English still holding his family hostage, Kancamagus was forced to make peace with the English at Wells. Following this agreement of peace, Kanacamagus was reunited with his family. After 1692, little is written about Kancamagus. It’s possible that once he recovered his family, he continued to fight alongside other Abenaki people, although that is purely speculation. His name lives on in the scenic road well-loved by leaf peepers. However, I'm sure that, as tourists drive the Kancamagus Highway, they have scant knowledge of the story of his life. Above: map of the Kancamagus Highway. Source: http://kancamagushighway.info/

3 Comments

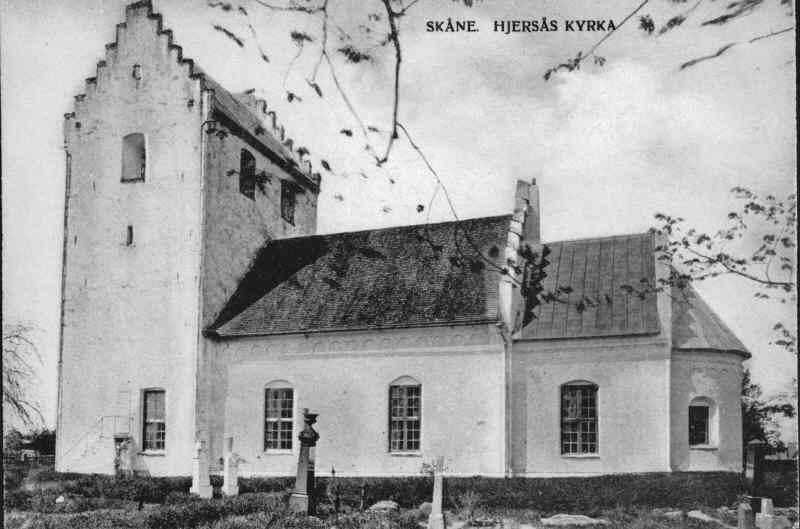

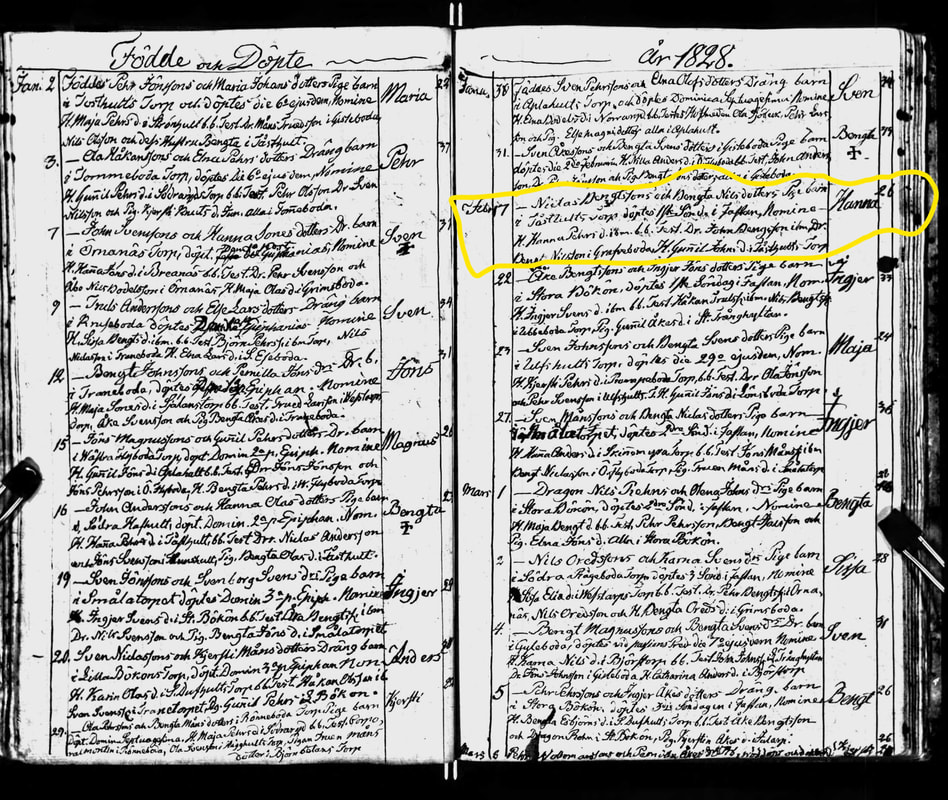

Below: My Swedish immigrant forebears in their farmhouse in Kingman, Maine circa 1910. Hanna is to the far right, her son my great grandfather Martin Johnson (originally Carlsson) is to the far left and the woman to the right of him is my great grandmother Marie Jensen. The boy on Martin's lap is his son Martin, who died in 1911 at age 10 of Hodgkins Disease. He died in the same house in Lawrence, Mass. where his sister, my grandmother, was born eight months later. I posted a picture of that house on Kingston Street in another blog post. On August 25, 1892, my great great grandmother Hanna Niklasdotter Jönsson departed her hometown of Hjärsås, Sweden, where she had been living, presumably since she married Carl Jönsson of that town on July 8, 1858. She would have been 64 years old. Below: Photo from the 1800s of the Hjärsås parish church. Her travel record in the parish record book states that she was traveling with her daughter Anna, age 26, unmarried. Their destination was listed as Kingman, Maine, meaning some other relative, presumably her husband Carl, had gone before them to buy a farm there. Why they did not end up in New Sweden, the swedish settlement up in Aroostook County, Maine, is unknown. Instead, they bought a farm in rapidly depopulating Kingman, Maine, probably for a song. As I explained in my review of the book Yankee Exodus, after the Erie Canal opened, the upland parts of New England rapidly depopulated. This was because cheap grain could come from the fertile lands of the Ohio Valley to New England by boat, making farming in places like Maine very uneconomical. Whatever Yankee farmer sold my Swedish ancestors this farm probably counted his lucky stars. Then he likely got on the next train to Oregon Country to seek his fortune in the west. Within a few years my ancestors had abandoned farming in Maine and moved to the mill town. Below: Birth record of Hanna Niklasdotter, Ignaberga, Sweden, 1828 Until I learned about Hanna's illegitimate daughter, born before she married Carl Jönsson, the most interesting thing going on from a genealogical perspective was that some of her children kept the Swedish naming convention, and called themselves Carlsson or Carlsdotter, while others (including my great grandfather), took their father's last name, Jönsson, as their own thus making it a family name. This led to some confusion for a while when doing research, and for many years I didn't realize my great grandather Martin Johnson (he even took the extra step of anglicising Jönsson) had a brother who went by John Carlson (anglicized from Carlsson). Then in 2011, I got the following message from another ancestry.com user: "Hi, Your Hanna C. is Hanna Niklasdotter, born in Örkened, Kristianstad, Sweden on 17 Feb 1828. Hanna's first daughter was Pernilla Persdotter (born outside of marriage in Hjärsås, Kristianstad on 2 Feb 1853) - She [pernilla] later married Andrew Johnson in Mananna, Meeker County, Minnesota in 1889 - Andrew was the sponsor of my wife's grandmother (father's mother), Ellen (Olson) Nelson.) Yours truly, Adolph Johnson" Since then, the descendants of Pernilla, the illegitimate daughter (and therefore my half-cousins) have invited me to their family reunions in Minnesota. Unfortunately I haven't been able to attend. Swedish society was apparently under a lot of stress in the latter half of the nineteenth century, with the old agrarian structures breaking down and a lot of income disparity. Pernilla also had a child out of wedlock, Nils, before she emigrated from Sweden and then had one more (Julius) with Andrew Johnson after their marriage. Below: More photos taken that day in Maine around 1910. The far right shows Hanna with her three children who had emigrated with her, Martin, Anna and John. She had a daughter Ingrid who emigrated to Denmark. She also had a daughter Lissa. Lissa arrived in Boston on 9 Aug 1888. She had left Dönaberga, Hjärsås, Kristianstad, Sweden on 13 Apr 1887. Not sure why there was such a delay between leaving her parish and arriving in Boston. I have not been able to locate her after arrival. Was she already deceased by the time of the family reunion in Kingman, Maine shown in these photos? i have decided to take up Amy Johnson Crow on her challenge to blog about 52 ancestors in 2018, one per week.

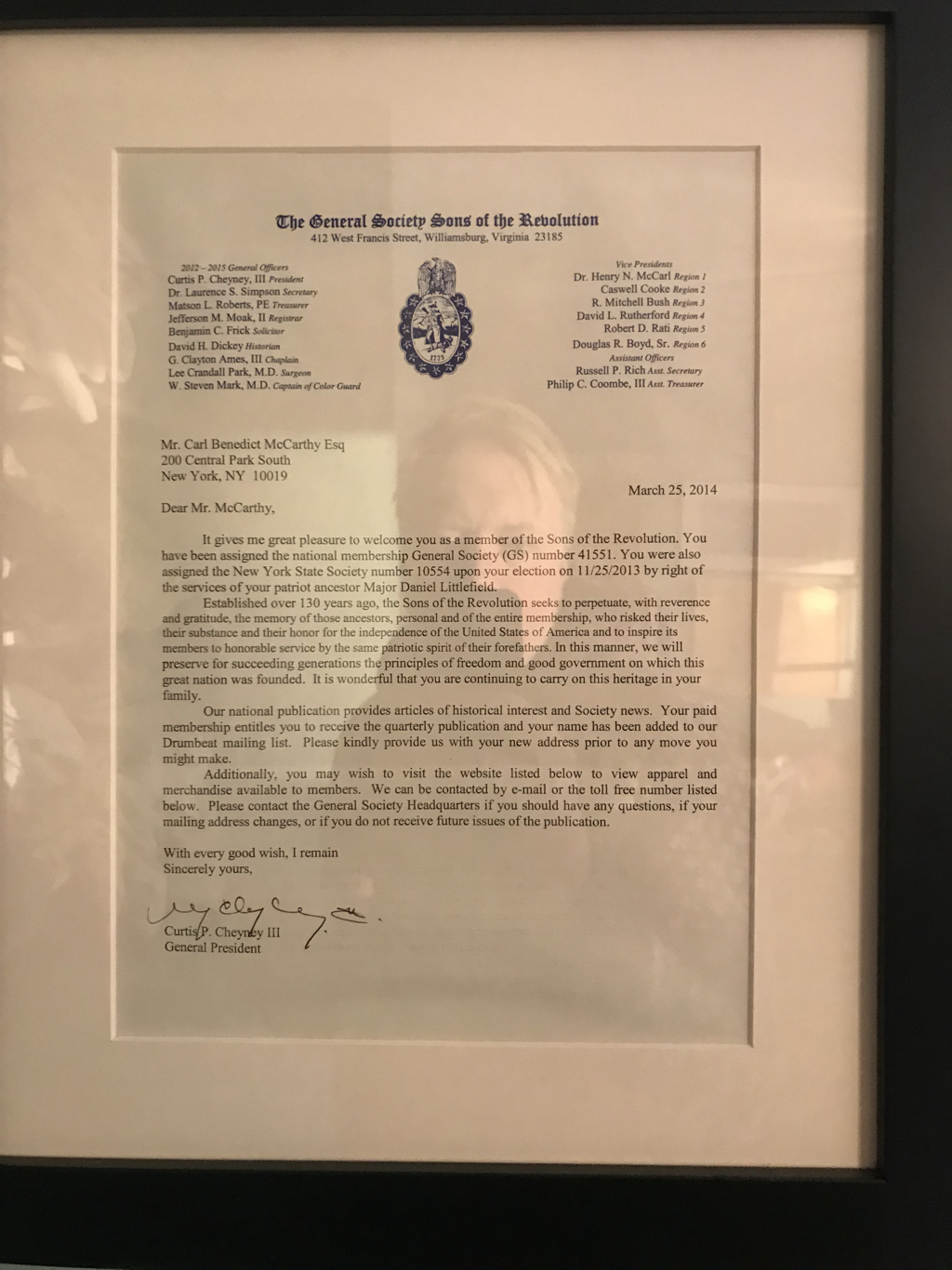

My first entry is my sixth great grandfather Major Daniel Littlefield of the Maine Militia. He was born in April 1749 in Wells and died July 26, 1779 with the rank of Major in the First Maine Militia. They were mustered for the ill-fated attack on a British fort in Castine, Maine in the so-called Penobscot Expedition. The event was also referred to as the Battle of Bagaduce. Eleven ships were lost, making it the biggest American naval disaster until Pearl Harbor. Daniel Littlefield drowned and his body was not recovered. There is a monument on the corner of Routes 1 and 9-B Wells, Maine, which reads "Major Dan'lLittlefield who was drowned at Castine July 1779: Aged 30 ys." According to George Buker’s book The Penobscot Expedition, British shot overturned the leading boat, drowning Major Daniel Littlefield and two of his men. Paul Revere, an artillery commander in this battle, faced a court martial investigation for allegedly abandoning his position and retreating prematurely back to Boston. I have done some research about this battle; it seems that only about half of the militiamen of York County who were mustered for this expedition actually showed up, because many were loyalist. On the basis of proving my lineage back to Major Daniel Littlefield, I joined the Sons of the Revolution in the State of New York (not to be confused with the Sons of the American Revolution a different group). The process of proving my lineage from scratch, basically, took two years and taught me about rigorous genealogical research. Below: Photo of the letter admitting me to the Sons of the Revolution genealogical society. Statute in Edson Cemetery, Lowell, Mass. depicting Passaconnaway The town of Haverhill was founded by charter of the General Court of Massachusetts in 1640 but title was not transferred until November 15th, 1642, when the great chief of the Pennacooks, the native inhabitants of the entire valley of the Merrimack from Pentucket (later called Haverhill) up to the river’s highest headwaters, transferred twelve miles of land along the river to form Haverhill.

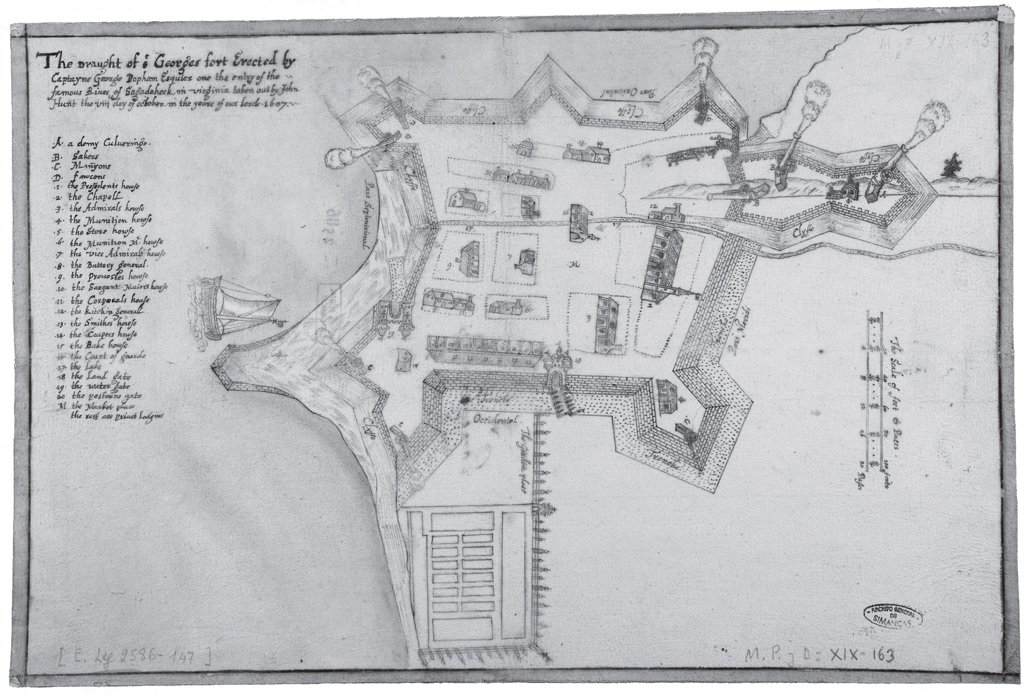

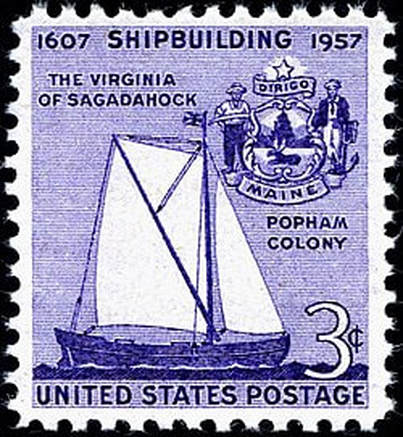

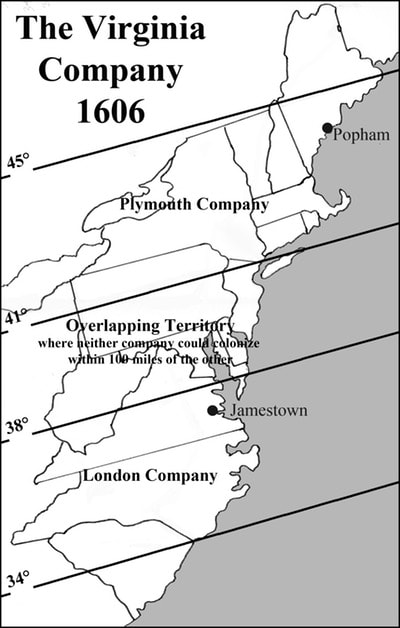

Pasaconnaway had been an impressive leader with magical powers. According to one early English account, “Hee can make water burne, the rocks move, the trees dance, metamorphise himself into a flaming man. Hee Will do more; for in Winter, when there are no green leaves to be got, hee will burne an old one to ashes and putting these into water, produce a new green leaf, which you shall not only see but substantially handle and carrie away; and make a dead snake's skin a living snake, both to be seen, felt, and heard.” Under his leadership, the Pennacooks, whose name aptly means ‘rocky place’ tribe, subsumed the neighboring tribes, the Wachusetts, Agawams, Wamesits, Pequawkets, Pawtuckets, Nashuas, Namaoskeags, Coosaukes, Winnepesaukes, Piscataquas, Winnecowetts, Amariscoggins, Newichewannocks, Sacos, Squamscotts, and Saugusaukes. Alas, the sale of Pentucket (Haverhill) to a group of Englishmen was one of the last historical acts of the Pennacooks. In the devastating war between the English and the natives in 1675– called King Phillip’s War after the Anglo nickname of native leader, Metacom, a Wampanoag from south of Boston – the Pennacooks sought to remain neutral. For safety during the conflict, they largely retreated to their mountain fastness near the headwaters of the Merrimack river high in the White Mountains. The Pennacooks came under suspicion and, upon their return to the lowlands at the end of the war, hundreds of their braves were captured en masse in a treacherous maneuver orchestrated by Captain Richard Waldron. This occurred at the Indian trading post in Dover, New Hampshire, known by the natives as Cocheco. Some of the Pennacook men were hanged for insurrection and the rest were sold into slavery in Barbados. The few remaining members of the tribe began to abandon Passaconnaway’s leadership. They retreated far to the north, to the mouth of the Saint-François River at its confluence with the St. Lawrence, to the reservation established by the French in Quebec, called Saint Francis in English. Today it is still a reservation, called Odanak, home of four hundred Abenaki with whom the Pennacooks merged. The great king Passaconnaway, a.k.a. Papisseconeway, a.k.a. Saint Aspenquid, died in 1682. The few remaining Pennacook warriors bore his body to the summit of Mount Agamenticus, it was said, and laid him to rest in a rocky cave. The alternative and more compelling story is that he was buried at the summit of Mount Agiocochook, now called Mount Washington, the highest mountain in New England, near the headwaters of the Pemigewasset River, itself the northernmost tributary of the Merrimack. Or his body was not borne there at all; rather he ascended there himself like Jesus Christ, whom many of the Indians had adopted by that time as their great spiritual leader. “There was to be a Council of the Gods in heaven and it was Passaconaway's wish that he might be admitted to the divine Council Fire; so he informed the Great Spirit of his desire. A stout sled was constructed, and out of a flaming cloud, twenty-four gigantic wolves appeared. These were made fast to the sled. Wrapping himself in a bearskin robe, Passaconaway bade adieu to his people, mounted the sled, and, lashing the wolves to their utmost speed, away he flew. Through the forests from Pennacook[modern-day Concord N.H., his royal seat]and over the wide ice-sheet of Lake Winnepesaukee they sped. Reeling and cutting the wolves with his thirty-foot lash, the old Bashaba, once more in his element, screamed in ecstatic joy. Down dales, valleys, over hills and mountains they flew, until, at last, enveloped in a cloud of fire, this ‘mightiest of Pennacooks’ was seen speeding over the rocky shoulders of Mount Washington itself; gaining the summit, with unabated speed he rode up into the clouds and was lost to view―forever!” Charles Edward Beals, Jr., Passaconnaway in the White Mountains, 1916. Thus basically ends the story of the Pennacooks, except for the place names they gave. Mount Passaconaway (4,043 ft.) is named for their leader. Mount Wonalancet (3,200 ft.) is named for his son. The Nanamacomuck Trail is named for his other son. The Kancamagus Highway is named for Passaconnaway’sgrandson, son of Nanamacomuck, who in 1689 led a brief and final Pennacook rebellion against the English. It was mainly fought not by Pennacooks but by “a throng of restless and vengeful Androscoggins.” Their crowning accomplishment was to murder the elderly Captain Waldron, who had sold so many of their kinsmen into slavery four decades earlier. The Pennacooks also left us with the names of most of the various tributaries of the Merrimack River: Contoocook (Near the Pines), Squannacook (Green Place), Suncook (Place of Villages), Piscataquog [or Piscatacook] (Great Deer Place), Souhegan (Waiting and Watching Place), Shawsheen (Serpentine), Quinepoxet (Pebbled Bottom). “The great, numerous, and powerful Pennacooks, where are they? Two hundred years have effaced every vestige of the race; they are rubbed out like a chalk mark on a black-board ; every trace of the blood is obliterated; no scion remains; they have withered as the grass beneath the pavement, and the places that knew them once shall know them no more forever. The few fragile and broken remnants of the race, dispirited, and dimly realizing their ultimate doom, long since turned their backs on old· familiar scenes, on the conqueror, and their faces to the setting sun, where year by year his domain is curtailed, and himself more closely environed, until, at no very distant day, he will be totally and finally obliterated from the face of this broad land, and become as much of a myth or tradition, as the centaur, the mastodon, or the sphinx.” J. W. Meader, The Merrimack River: Its Source And Its Tributaries (1869) His son Wonalancet, his daughter Wenunchus and his grandson Kancamagus have their own interesting stories covered in other blog entries.  The "Hunt Map" showing Fort St. George, the fortification at the short-lived Popham Colony Everyone knows the story of the Plymouth Colony of 1620, revisited every Thanksgiving, and many people have at least some notion of the Puritan settlement of Massachusetts Bay Colony. However the English colonization of New England was sometimes a messy affair full of false starts and paper claims, especially to the north of Massachusetts Bay. The story of New Hampshire (which managed to break away from Massachusetts for good in 1741) and Maine (which took until 1820) can be covered in other blog entries. Here are some notes on the short-lived Popham Colony of 1607. Until this year I had never heard of it. The Popham Colony—also known as the Sagadahoc Colony—was a short-lived English colonial settlement in North America that was founded in 1607 and located in the present-day town of Phippsburg, Maine, near the mouth of the Kennebec River by the proprietary Virginia Company of Plymouth. It was abandoned after a year despite low mortality. The first ship built by the English in the New World was completed during the year of the Popham Colony and was sailed back across the Atlantic Ocean to England. The pinnace, named Virginia of Sagadahoc, was apparently quite seaworthy, and crossed the Atlantic again successfully in 1609 as part of Sir Christopher Newport's nine vessel Third Supply mission to Jamestown. Postage Stamp from 1957 Commemorating the "Virginia of Sagadahock"  A contemporary monument to the ship Virginia of Sanghedoc at the Popham site On May 31st, 1607, the ships Gift of God and Mary and John departed for the intended Popham Colony carrying some 120 colonists - a slightly larger group than had travelled from London to Jamestown. Unlike that rival expedition, the Plymouth group took just nine council members and half-a-dozen other notable gentlemen, with the majority being mainly soldiers, craftsmen, farmers and traders, their objective to reach the coast of 'North Virginia' at a latitude of about 43 degrees north. The Gift of God arrived at the mouth of the Sagadahoc River (now the Kennebec in Maine) on August 13th, and Mary and John followed three days later. • The exact site of Popham Colony was unknown in modern times until it was discovered in 1994 and excavated by archaeologists for next ten years. It was within a stone's throw of present day Fort Popham, built during the U.S. Civil War to protect the mouth of the Kennebeck. • Discovery was aided by the picture-plan of Fort St. George that was drawn on site by one of the colonists. It is unique since it is the only detailed drawing that exists for an initial English settlement anywhere in the Americas. Fortified with a ditch and rampart, the enclosure contained a storehouse, chapel, guardhouse, and other public buildings, as well as residences for the colonists. The fort was defended by nine guns that range in size from demi-culverin to falcon. The boat built by the colonists, the pinnace Virginia, floats offshore although it could not have been completed by the date of the map. • The Hunt map had been lost to history until it surfaced in a royal archive in Simancas, Spain in 1888. It ended up there via a 1608 dispatch to the Spanish king from Don Pedro de Zuniga the Spanish ambassador in London. The dispatch also contained a sketch of the English colony at Jamestown also founded in 1607. How he got his hands on hunt’s map is unclear. • The 1607 founding of the Popham Colony (also called Fort George) was the second attempt by the Plymouth England branch of the Virginia Company which had been given a charter to coastal North America above the 38th parallel, roughly modern northern Virginia. The more famous Virginia Company of London was given a charter south of the 41st parallel (roughly modern NYC). Note the geographic overlap. • The Richard, a ship sent by the Plymouth Company in August 1606 under the command of Captain Henry Challons, never reached its intended destination in what is now the state of Maine, being intercepted and captured by Spanish forces near Florida in November 1606. • The Popham Colony was abandoned because leader George Popham died (his rich uncle had financed the expedition), and second-in-command Robert Gilbert learned he had inherited a title and landholdings back in England. Below: Map Showing the lands granted to the two Virginia Companies, the more famous Virginia Company of London (founders of Jamestown) and the Virginia Company of Plymouth (founders of the unsuccessful Popham Colony - later, they took jurisdiction over the Separatist colony that incidentally landed in their claim, which was named Plymouth). Note the overlapping area between the two companies. SOURCE: www.mainestory.info/maine-stories/popham-colony.html (Pat Higgins)

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed