|

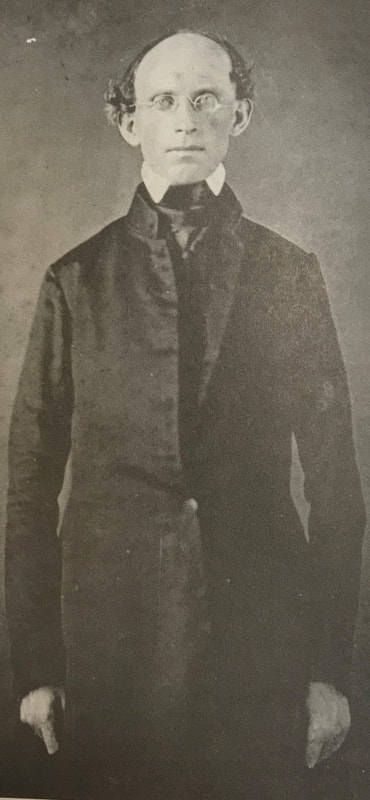

Below: Father James D. O'Donnell O.S.A., who brought the Augustinian order to Lawrence (O.S.A.= Order of St. Augustine) The story of the Augustinian "friars" in the vicinity of Lawrence, Mass. is one of the more unlikely happenings in our history. It is also a tale of a small number of dedicated men bringing great benefit to the area. Who are the Augustinians? Since the dark ages, the Catholic church has had monastic orders such as the Benedictines, in which dedicated priests and non-ordained members live a monastic existence, praying constantly to God and contemplating his wonders. In the 1200s, a different kind of order sprang up: mendicants, meaning they wandered instead of becoming hermits, and lived off local charity rather than estates. Like the monastic orders, they had priests as well as monks (essentially). The main mendicant orders are the Franciscans, named after Saint Francis of Assisi, and the Dominicans, named after Saint Dominic de Guzmán. Regardless of whether members are ordained priests or not, they are generally called friars. The Augustinian order was founded in 1256 by uniting four groups of hermits into a new order with a mendicant approach. It was never as prominent in size as some of the other orders, but nevertheless spread in missions to England, Ireland, the German speaking lands (Martin Luther was an Augustinian before he had his split with Catholicism) and elsewhere. The Augustinians come to America When Reverend Matthew Carr, a 41 year old Irishman, arrived in 1796 as the first Augustinian in America, “there was only one Catholic diocese in the whole immense territory, from Georgia to New Hampshire and from the Atlantic Coast to Mississippi." (quoting Ennis, No Easy Road: The Early Years of the Augustinians in the United States). Catholics at that time numbered about 35,000 in a total population of nearly four million. They were concentrated chiefly in Maryland and Pennsylvania (Baltimore was the sole diocese), but small groups of Catholics could be found elsewhere. Numbers of the Augustinian order in America increased slowly, to about 14 after a few decades. For the first forty years, all the Augustinians in America were Irish-born. Arthur Ennis, who wrote the preeminent early history of the order in America, surmises that their Irish background made them particularly suitable for lone efforts in their "mission":

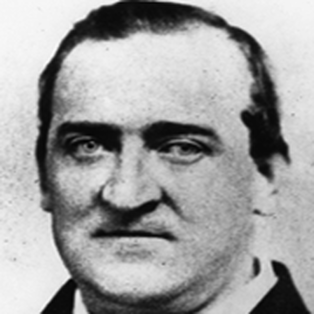

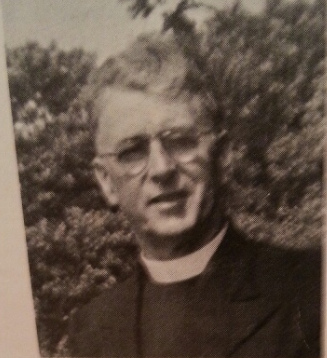

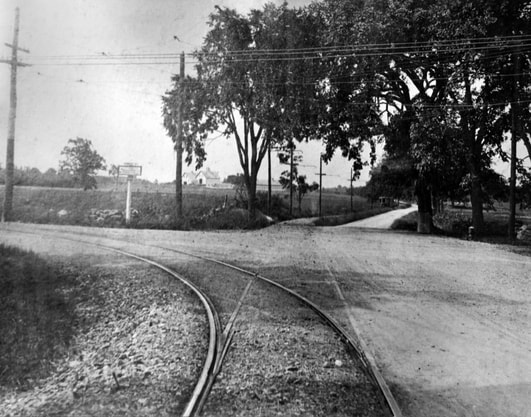

They launched their mission in Phiadelphia and built a church, St. Augustine's, that later was burned in 1844 by a nativist mob. They nevertheless persevered. They founded Villanova College around that time in a Philadelphia suburb. It would quickly become a seminary to train priests in the Augustinian tradition, and ultimately one of the more prominent Catholic universities in the United States. Below: Villanova College in 1849. Photo from Wikipedia. The Mission to Lawrence: Father James D. O'Donnell O.S.A. The Augustinian connection in Massachusetts came about through the work of James O’Donnell. The Irish-born immigrant was the first Augustinian priest ordained in the United States, in 1837, after entering as a novice in 1832 at St. Augustine's in Philadelphia. He was on the faculty of Villanova when the school opened in 1842. According to Ennis, how the Augustinian ended up in Lawrence is something of a mystery. “Father James had departed from Philadelphia early in 1848, apparently in a rebellious mood; his ambition went unsatisfied, he felt frustrated, bored with the small tasks assigned to him. He went off on a visit to Ireland, and before the end of the year he was back, hard at work now in Lawrence, assigned there by Bishop Fitzpatrick of Boston. How this came about is a puzzle. Although there is no record of permission given to him by his Augustinian superiors, he evidently received approval for his move to Lawrence, granted perhaps after the fact, for he would not otherwise have been acceptable in the diocese of Boston." Lawrence at that time had just been established and was a boomtown. Roads were being laid out, institutions were being constructed, such as libraries and schools, and mill buildings were going up everywhere. Catholic immigrants were pouring in. Destitute Irish laborers fleeing the potato famine had taken up vacant land just south of the river and soon had built over a hundred shanties. They were put to work, digging the canals and constructing the great stone dam, the largest dam in the world, that provided water power to the mills. According to a census taken in 1848, the town had a population of nearly 6,000, up from a couple dozen Yankee farmers two years earlier. Of that number, 2,139 were natives of Ireland, and presumably the vast majority of them were Catholic. Father James immediately embarked on a building spree to meet the needs of the burgeoning Catholic population. Although a small wooden church, Immaculate Conception, had been built in 1846 by a Father Charles Ffrench (not a typo), another mendicant friar (albeit a Dominican), Father James surmised the need for more houses of Catholic worship. He arrived in Fall of 1848 and promised that he would be saying Mass in a new church on New Year’s day. When the day came, the new church was barely walls and timbers, with snow falling through the open roof. However he said Mass as promised and a few months later the church was finished, being the first St. Mary’s. He financed the construction efforts with a church bank, taking deposits from his parishioners at interest. A few pennies a month from each of the couple thousand members added up, and lucky for him there were no bank runs (although in 1882 there was a run on St. Mary’s bank when a large number of depositors sought to withdraw their savings during a labor strike)(Source: Ennis). O'Donnell barely had time to rest before he set about building a larger church, this time of stone, on the same site. The construction took place all around the little wooden church, and then the new, larger church was completed, the wooden structure was torn down and its beams were used to construct a rectory for the priests. Then, in 1861, O'Donnell constructed a massive replacement church, also called St. Mary's, after buying up land on both sides of Haverhill Street. This structure, which burned down in 1967, became the St. Mary's school following the construction of the (still-standing) St. Mary's "cathedral" nearby on Haverhill Street in 1871. Below: Photo from the Lawrence Public Library archives of the original St. Mary’s granite building, which became the second St. Mary’s school. This building was destroyed by fire in 1967, after which time the high school became solely a girl's school. St. Mary’s High School for girls began instruction in 1880 and closed in 1996, when nearby Central Catholic high school began admitting girls. St. Mary’s Elementary School closed 2011. Source: Louise Sandberg, library archivist, on her Queen City blog. Father James also organized the parochial school system with the help of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur and began ministering to some of the nearby Catholic communities. He regularly visited Methuen and Ballardvale (the main mill section of Andover at that time). On November 22, 1853 he blessed the first Catholic chapel in Andover. This church, St. Augustine's, survives and prospers to this day under the auspices of the Augustinian order, in a later-constructed building. O'Donnell's strenuous activity must have taken a toll on his health, for he died quite unexpectedly on April 7, 1861, only days before his fifty-fifth birthday. No cause of death is recorded, but his illness was sudden and brief for on the previous Sunday he had presided at Easter services. The Augustinians in Lawrence after James O'Donnell's near one-man-show Following the untimely death of Father James, a series of prominent Augustinian priests ran things in Lawrence, although for most of the following decades they were only two or three on the ground. These included Rev. Ambrose McMullen, O.S.A. (in Lawrence 1861-1865), Rev. Thomas Galberry, O.S.A (in Lawrence 1867-1872 I believe), Rev. John Gilmore (in Lawrence 1872-1875). I say prominent mainly because they later went on to do great things, such as serve as president of Villanova (Mullen and Galberry), or become a bishop of the diocese of Hartford (Galberry). Mullen returned to the area after his tenure as college president, serving as pastor of St. Augustine's in Andover, where he died on July 7, 1876 at age 49. Photo below: Rev. Ambrose McMullen, O.S.A. Father Mullen was first stationed at St. Augustine's in Philadelphia and later in Lawrence, Massachusetts, where he continued the work of Father James O'Donnell. From 1865 to 1869, he was President of Villanova College. His next assignment was to St. Augustine's, Andover, Mass., until his death in 1876. He is buried in Saint Mary's Cemetery in Lawrence, Massachusetts. The construction of St. Mary's was followed by the organization of numerous churches in Lawrence in addition to that church and Immaculate Conception. Six other Catholic churches in north Lawrence were ultimately under the care of the Augustinians, many serving immigrant communities: St. Francis (Lithuanian Catholic) on Bradford Street, dedicated 1905 closed 2002; Sts. Peter and Paul (Portuguese Catholic) on Chestnut Street, dedicated 1907 closed 2004; Church of Assumption of Mary (German Catholic) on Lawrence Street (where I was baptized as an infant in 1971), dedicated 1897 and closed 1994; Holy Trinity (Polish Catholic) on Avon Street, dedicated 1905 closed 2004; St. Laurence-O'Toole, dedicated 1903 closed 1980; and St. Augustine's on Ames Street, where I went to Mass as a child, merged with St. Theresa's of Methuen, 2010, with masses celebrated once weekly in the St. Augustine's building, now called a chapel. Here is the Boston archdiocese list of merged or suppressed churches. My great-grandfather's nephew, Rev. Daniel Driscoll O.S.A. (1886-1963), was educated at Villanova and finished up his priestly vocation at St. Mary's in Lawrence. The 1940 federal census lists him living in the St. Augustine's rectory on Ames Street as the head priest along with two other priests; he later was at St. Mary's. Below: Photo of my great-grandfather's nephew, Father Daniel Webster Driscoll, O.S.A. (circa 1950?) of Lawrence, Mass. Served as priest at St. Augustine's, Lawrence, then St. Mary's. Founding of Merrimack College, North Andover, in 1947 Merrimack College was founded in 1947 by the Order of St. Augustine at the invitation of then Archbishop of Boston, Richard Cushing. It was founded to address the needs of returning G.I.s who had served during World War II, and is the only other Augustinian college in the U.S. besides Villanova. Rev. Vincent A McQuade, O.S.A., was a driving force behind the establishment of Merrimack and served as its first president. During his twenty two years in that position, he developed the college into a vital resource in the Merrimack Valley. "Vincent Augustine McQuade was born in Lawrence, Massachusetts on June 16, 1909, the son of Owen F. and Catherine McCarthy McQuade. The product of a Catholic home, Father McQuade was a son and a brother who attended St. Mary’s Grammar School, graduating in 1922. In August the same year, at age thirteen, he was received as a Novice in the Order of Saint Augustine. A graduate of Villanova University in Philadelphia, Father McQuade was ordained in 1934 and received his Master’s and Doctoral degrees from Catholic University in Washington, D.C. Father McQuade was a member of the faculty at Villanova from 1938 through 1946 who served in a succession of administrative roles including Acting Dean and Assistant to the President. Father McQuade also held a number of positions that required him to minister and advocate for servicemen, befitting the future founder of a college conceived in part for returning veterans." (source: https://merrimack.smugmug.com/History/The-College-on-the-Hill/) Below: Future site of Merrimack College, Wilson's Corner, North Andover, 1946. Source: same Today, Merrimack College has:

Photo below: Merrimack College, North Andover, "a selective, independent college in the Catholic, Augustinian tradition whose mission is to enlighten minds, engage hearts and empower lives". Source: college website.

6 Comments

A statue of a saint stood benevolently on the widow-shelf surrounded by plants basking in the sunlight. He was about ten inches high and composed of a dark brown, heavy, rough-cast metal. “Who is that?” I remember asking my mother, when I was about five years old. We learn so much about our world at our mother’s knee. I was a big beneficiary of having a teacher for a mother. “St. Francis of Assisi,” she told me. “My favorite saint,” she added, “along with Teresa the Little Flower.” Who was this St. Francis, hand raised, looking down upon us from the shelf? The impression I got of him, from my social-justice pursuing, liberation theology-espousing, National Catholic Worker-subscribing parents, was of a barefoot, soft-talking, sentimental, free-thinking, anti-authoritarian, tree and animal hugger and social activist. “He loved the animals, and the children, and most of all the poor,” she told me. Soon we were supplementing our Sunday worship with journeys with men and women who strove to live like St. Francis. The Christian Formation Center was founded in the late 1960s next to the St. Francis Seminary on River Road, West Andover, near the Tewksbury town line amid expansive fields and lawns that had once been a dairy farm. Down the slope, the Merrimack River ambled in the distance. The seminary there trained Franciscan priests from 1930 until 1977. The grand, colonial-looking building of the seminary was finally torn down last year to make way for high-end senior housing. Across the street stood the monastery of the sisters of Poor Clare, a female monastic order named after St. Clare of Assisi (1194-1253), the first follower of St. Francis of Assisi (1182-1226). The female Franciscans, nuns, and the male Franciscans, monks and priests, pursued their “formation” into the Franciscan way, alongside “secular” Franciscans, laity who were neither monastic nor clergy. And this is where the Christian Formation Center came in. Formation took many decades, and they worked together at attempting to achieve perfection into the ways of St. Francis. In contrast to the seminary and the monastery, the formation center was a modern structure, set way back from the road among the fields. It was supposed to offer alternative forms of religious expression, albeit within the teachings of St. Francis. Remember, this was the golden period after the reforms of the second Vatican Council, when modernization and making the Church more relevant to the times was the order of the day. Pope John XXIII, who had ushered in Vatican II, had himself been a Secular Franciscan before he became a priest, living an idealized life of poverty and holy contemplation as worked for the poor. Unlike our local church, St. Augustine’s on Ames Street in Lawrence, the Christian Formation Center had no pews for Mass. Seating was auditorium-style, with individual seats arranged in a curvature around an altar that was more like a central performance stage. I think kids sat cross-legged on the floor in front, where the priest and assembled clergy fawned over them. Fully-robed Franciscan priests and brothers walked the outdoor gardens and breezeways, and, when it was time for Mass, they mounted performances of tambourines, acoustic guitars and folk melodies, along with the nuns. We would regularly sing Michael Row the Boat Ashore when we attended Mass there. (In case you don’t know this song, is is a Negro Spiritual that was popular in the civil rights movement and among left wing activists.) These were no crusty parish priests, giving tired homilies and leading the traditional choir. Apparently, the Christian Formation Center sought to attract non-Catholic Christians to its worship, either in an ecumenical outreach that was in the spirit of the times, or as part of some kind of subtle Catholic proselytizing, I don’t know. The whole zeitgeist of the service was quite different from the other Catholic churches where I had attended worship. For one thing, there was speaking in tongues, and a lot of Catholic Pentecostals. Are there Catholic Pentecostals anymore? Other mounting was also going on. As my mother tells it, the Seminary closed in 1977 shortly after we started going, “because a bunch of the nuns got pregnant by a bunch of the seminarians and they all left the religious orders to get married.” I have no idea if it’s true, but we did stop going to the Christian Formation Center by about 1980 if memory serves me. As a secular formation center not tied to the clergy, it could in theory continue despite the closing of the seminary…and the nuns are still there, although they have a small, modern monastery now. Their old facility was torn down to make way for luxury housing, although the Christian Formation Center building survives to this day as a private school for autistic children. Anyway, within a few years, the entire tone of the Church changed. Although there was no return to the Latin Mass, within the Church the social justice trends of the 1970s gave way to the sexual politics of the 1980s, as Pope John Paul II led a traditionalist backlash. The last time my mother set foot in a church for Mass, other than for funerals or weddings, was when my younger sister had the sacrament of penance (first confession) at St. Augustine’s in 1984. After the CCD teacher repeatedly gave lessons on the place of women (in the home, subservient to men), my mother walked up to him after class to give him a piece of her mind. Things in her church had been changing for some years, and this must have been the last straw. She never went back to Mass, although she still has her statue of St. Francis looking over her in the kitchen. Above: Photo of the Melmark School, River Road, Andover, Mass., the former Christian Formation Center. Photo source: Melmark School website.

Below: A more expansive view of the facility when it was built. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed