|

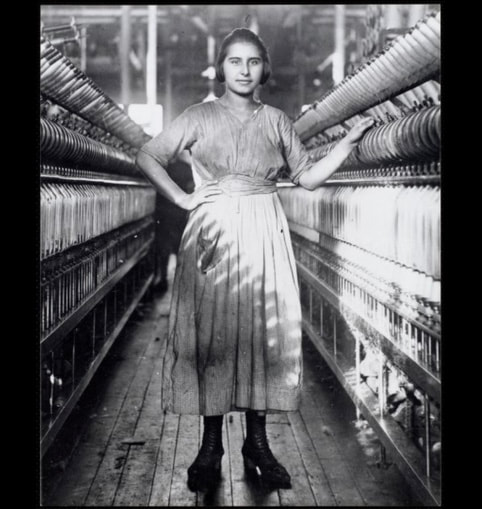

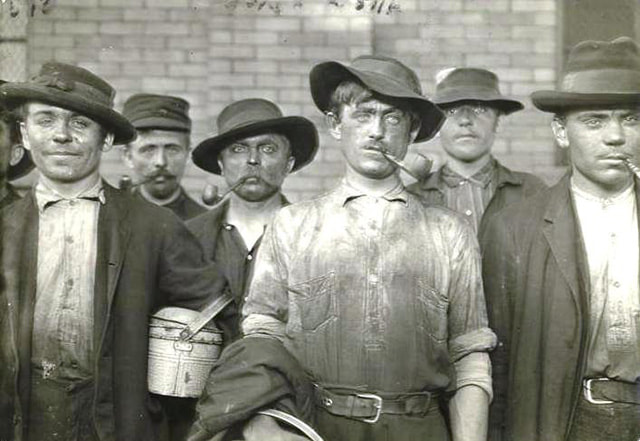

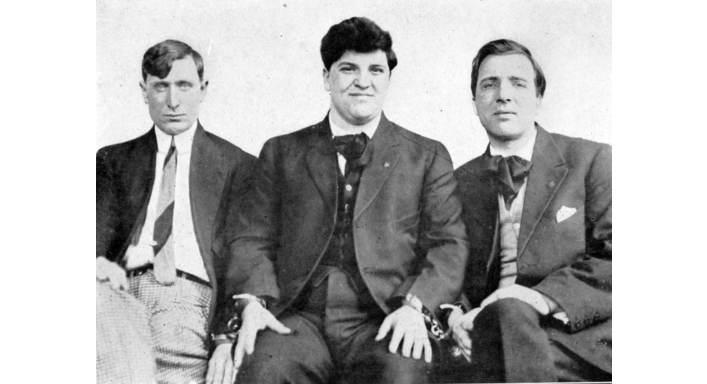

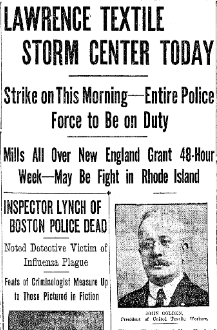

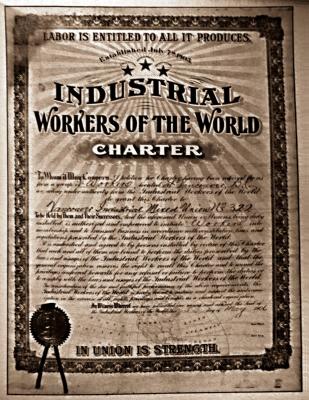

Above: Mill district panorama, circa 1910. Lawrence, Mass. (Source: Lawrence History Center) A LONG READ (sidebars about related topics are in blue font) In 1912, the city of Lawrence, Mass., population 85,000, was the worsted woolen capital of the world. Founded in 1845 as a planned industrial city, by the time of the strike, it employed 37,000 mill workers. Most were employed by the American Woolen Company, the country’s preeminent manufacturer of worsted woolen cloth. Over 7,000 workers toiled in the Wood Mill and Ayer Mill, that company’s main facilities. Other major mills of other manufacturing companies included the Washington Mill (5,000 employees) and the Arlington Mill (7,000 employees). Other mills also employed substantial numbers of workers. Not all hands were equal. Workers in skilled jobs – loom fixers and mechanics – were paid one rate, while “operatives” who tediously watched over automatic looms, were paid the lowest. A subsequent Congressional investigation into the strike said the average weekly pay for all workers was $8.76. For the most skilled workers, average pay was $11.39 a week. For Italians, the average was only $6.81, not enough to pay for food and rent in most cases. Whole families worked to make ends meet. (Source: Congressional Report on the Strike of Textile Workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts, 1912) Below: Mary Tomacchio, age 15, Ayer Mill (photo by Louis Hine). Louis Hine did portraits of over a dozen Italian immigrant children laborers in Lawrence. A decade earlier, there hardly were any Italians in Lawrence. In 1890, Lawrence had only 263 people born in Italy. Apparently, in 1891, around forty of them were brought in by people-smugglers known as padrone to work as strikebreakers (source: Immigrant City by Donald Cole). Sidebar about the padrone labor system: "Approximately 35 million immigrants entered the United States between 1820 and 1924, including 4 million Italians. They came largely from southern Italy, where an increasing population strained already meager resources. It became common practice for construction managers in Massachusetts and other states to hire labor agents (or padroni) to provide labor gangs for projects such as digging, laying railroad tracks, and supplying builders with materials. The padrone received a fee for each laborer he provided, and the laborer was provided with a steady income and a place to live in exchange for his labor. The padrone would provide housing, food, medical care, transportation, and, at times, liquor, charging most of the laborer’s wages. In many cases, the accommodations provided by the padrone were inadequate and sometimes nonexistent. After spending several months in backbreaking, dangerous work, the laborer would often be in debt to the padrone. These conditions led to sudden strikes, causing disruptions in various commercial construction ventures. For example, in the 1893, on the construction of the Wachusett Water project near Clinton, Italian laborers struck six times during the first four years of work. By 1900, there were approximately three thousand Italian laborers in Boston and some seven thousand in Massachusetts. Over the next few years, thousands more arrived in the Commonwealth in search of work. In 1904, a few Italian workers joined the building trades unions, but the vast majority of Italians on job sites remained unorganized and in bondage to the padroni. The Italian consul in Boston, Baron Gustavo Tosti, believed the only way that Italian laborers could erase the stigma of “cheap labor” that attached to them would be to organize their own union. An immigrant banker from Boston’s North End named Domenic D’Alessandro became a close ally of Tosti. D’Alessandro used his organizing talents to create the Italian Laborers Union (ILU) in April 1904, which became a key weapon in the attack on the padroni system. With the help of the Italian consul and the American Federation of Labor, the ILU in Massachusetts eventually encouraged the enactment of laws that put many padroni out of business and alleviated many injustices experienced by Italian immigrants." (Source: Commonwealth of Toil- History of Massachusetts Workers and their Unions, by Juravich et al 1996) Above: Italian Steelworkers circa 1910 by Lewis Hine. As the most recent immigrant group, Italians in the first years of the twentieth century often did the hardest, dirtiest jobs At that early time, most Italian workers were transient men who came to work and then intended to go back home again. In 1900, there were 963 Italian-born persons, still most of them men. But by 1915, there were almost 9,000 Italian born persons and their American-born children. “The exodus of southern Italians from their villages at the turn of the twentieth century has no parallel history,” said one writer. “Of total population of fourteen million in the South at the time of national unification 1860, least five million – more than third of the population – had left to seek work overseas by the outbreak of World War. The land literally hemorrhaged peasants.” (Source: From Italy to Boston's North End: Italian Immigration and Settlement, 1890-1910 by Stephen Puleo, master’s thesis, University of Massachusetts Boston.) Italian workers, as newcomers, were mostly likely to be overcrowded into overpriced tenements near the mills of Lawrence. Many lived with, or were, borders to make ends meet. The Italian immigrants were clustered around the eastern end of Common Street (if they were from Sicily) or Oak and Elm Streets (if they were Neapolitan). They had higher rates of mortality, despite a better diet, and high rates of child labor. In other similar nearby enclaves lived other recent immigrant groups, Lithuanians, Poles and Syrians. These groups comprised most of the rest of the lowest paid laborers in the mills besides the Italians…and the bulk of the non-Italian strikers. In contrast, the Irish, now established three generations, and French Canadians, one or two generations, were generally not big participants in the strike. 1911 photo of alleyway in Lawrence tenement district (source: White Fund) How did the strike come about? Thanks to progressive political activism by well-meaning socialites from Boston, the Massachusetts legislature mandated a reduction in the work-week from 56 hours to 54 hours, effective January 1, 1912. The mill owners resolved to reduce pay by two hours because of fewer hours worked. None of the Lawrence mill workers seemed to mind that they were dismissed twenty minutes earlier each day. However, when the first pay packets came on Friday, January 12, there was going to be hell to pay. Workers said they could not afford to lose the few pennies represented by those two hours. The Lawrence Sun of Thursday, January 11, 1912, carried the following news item with large head lines across two columns: ITALIAN MILL WORKERS VOTE TO GO OUT ON STRIKE FRIDAY. IN NOISY MEETING 900 MEN VOICE DISSATISFACTION OVER REDUCED PAY BECAUSE OF 54-HOUR LAW A mass meeting of almost all the Italian mill workers of this city was held Wednesday evening in Ford’s Hall. The object of the meeting was to discuss the new 54-hour law and to hear the reports of the different committees which had interviewed their respective mill agents. The reports were unfavorable to the 900 people who jammed the hall. It was decided that all Italians of all the mills strike on next Friday evening. They claim that the wages which they now receive because of the 54-hour law are not sufficient for them to live on, and that they want their pay raised to the amount which they formerly received. The meeting was presided over by Angeline Rocco. Who was this Angeline (or Angelo) Rocco? Rocco was a twenty-eight-year-old junior at Lawrence High School, a summer mill worker, and secretary of the Italian branch of Local 20 IWW, the International Workers of the World, which had only around 400 members in Lawrence. As I explained in my blog post about the 1919 Strike, the IWW was the union of the unskilled workers. It called for class warfare. Their charter read “The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of the working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life." You can see Angelo Rocco talking about the strike in this video taken in 1977: The Strike Here is how the 1912 strike went down. According to the Congressional strike report, “On the Friday morning succeeding the strike, at the Everett mill it was evident that the employees expected their pay envelopes to show reduced earnings and that they determined upon resistance to a reduction in earnings. In one of the large departments the non-English-speaking employees by 9 o’clock had begun to leave their work, to congregate in groups, and to show signs of excitement. Word to this effect reached the pay department and fearing an outbreak the distribution of the pay envelopes was delayed. A short time afterwards word came from the mill that rioting had begun in some departments and that employees were stopping machinery and driving other employees from their work. A call was sent to the mill office for police, and a small number of police responded. They failed to get the employees creating the disturbance out of the mill, and a call was sent in for more policemen. Shortly after the arrival of the second group, the strikers—a small number at a time—began to come out of the mill and congregate just outside the mill gates. Those taking part in this demonstration and who formed the crowd outside the mill gates were principally Italian workers. As the crowd at the gate was increased by accessions from those within the mill, some of the leaders began to make speeches, and after a short time the entire crowd, carrying an Italian flag and a large number of United States flags, started on a march toward the Wood mill of the American Woolen Co. The Wood mill is several squares below the Washington mill, and the striking Italians reached there in a short time, and rushed the gates and secured entrance to the mills, the gatekeepers and watchmen being unable to stop the inrush. The strikers then rushed into the different rooms of the Wood mill, shutting off the power from the machines and calling upon the workers of the Wood mill to join with them in the strike. After about one-half hour of disorder in the Wood mill the strikers withdrew, accompanied by a considerable number of the employees of the Wood mill in the departments which the strikers had been able to reach. In connection with the morning of disorder, the strikers in marching past one of the smaller mills destroyed a number of windows by throwing ice through them. Shortly afterwards a collision occurred between the strikers and the police, in which the police brought their clubs into use.” A committee, led by Angelo Rocco, was formed and they telegraphed the general executive board of the IWW in New York to send someone to lead the strike. On Saturday, January 13, Joseph (Giuseppe) Ettor of the IWW executive board arrived in Lawrence from New Jersey. Described by one critic as having "the cunning of the Syrian and the eloquence of the Italian," Ettor’s parents were from Italy and he spoke fluent Italian. Ettor was soon joined by Arturo Giovannitti, an Italian born poet and orator who was director of Il Proletario, a radical workers’ newspaper. Below: Italian-American strike leaders Ettor and Giovannitti arrive in Lawrence, January 13, 1912 SIDEBAR: Who were Ettor and Giovannitti? Here is a description of them from a book about Italian radicals in America in the early 20th century: “Only twenty-six years old, with a shock of curly black hair and a cherubic smile, Ettor looked more like a mischievous street urchin than a fiery labor agitator and the IWW’s principal organizer for its eastern branches. Born to Italian parents in Brooklyn, in 1886, Ettor grew up in Chicago and California and joined the SPA while still a teenager, working as an iron worker in a San Francisco shipyard. He joined the IWW in 1905 and served as an organizer among West Coast lumbermen, miners, railroad workers, and construction gangs. Elected to the IWW’s general executive council in 1908, Ettor moved East the following year. His proficiency with foreign languages (he was fluent in English and Italian, and understood Polish, Yiddish, and Hungarian) proved invaluable when dealing with immigrant workers such as those in Lawrence. The strike would prove to be the greatest triumph of his career in the labor movement. Ettor perceived at the outset that Italians mill workers, by virtue of their superior numbers and militancy, would constitute the backbone of the strike. To join him as co-leader of the Italians, Ettor invited Arturo Giovannitti, the director of Il Proletario, who arrived on January 20. At twenty-eight, Giovannitti was an elegant figure, taller and thinner than his stocky comrade, with handsome features and brooding eyes. Giovannitti had an unusual background for a sowersivo [“subversive”]. As a rebellious and melancholy youth from the middle class in Campobasso (Molise), Giovannitti rejected the prospect of life among the provincial bourgeoisie and migrated to Canada at age sixteen, supporting himself briefly as a mine worker and railroad laborer. Well educated but guided by religious and mystical tendencies, Giovannitti found work at a Presbyterian mission for Italians in Montreal, and studied English and theology at McGill University. He continued his religious studies at Columbia University’s Union Theological Seminary in 1904, while working at a Presbyterian mission in Brooklyn. After another stint at a mission in Pittsburgh, Giovannitti’s flirtation with Protestantism ended, and he embraced syndicalism under the influence of Carlo Tresca, with whom he maintained a lifelong friendship. Back in New York and unemployed, Giovannitti spent many a winter’s night sleeping on a bench in Little Italy’s Mulbury Park until he found work as a bookkeeper and joined the editorial staff of Il Proletario. Thereafter, his rise to prominence in the Italian syndicalist movement was rapid, becoming the director of the newspaper and FSI secretary in 1911. By that time, Giovannitti had also distinguished himself as the leading poet of the Italian immigrant Left, although much of his best poetry (in English) would soon be inspired by the ordeal that awaited him in Lawrence. Giovannitti’s role in the strike was that of the charismatic orator; his “Sermon on the Common” (in English), echoing Christ’s “Sermon on the Mount,” uplifted strikers’ spirits and strengthened their resolve to fight." (Source: Carlo Tresca, Portrait of a Rebel, by Nunzio Pernicone, AK Press 2010) The strike committee, made up of representatives of 43 different nationalities, put forward its demands on Sunday, January 14.

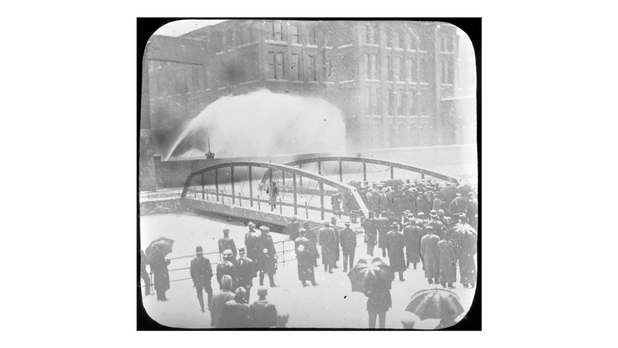

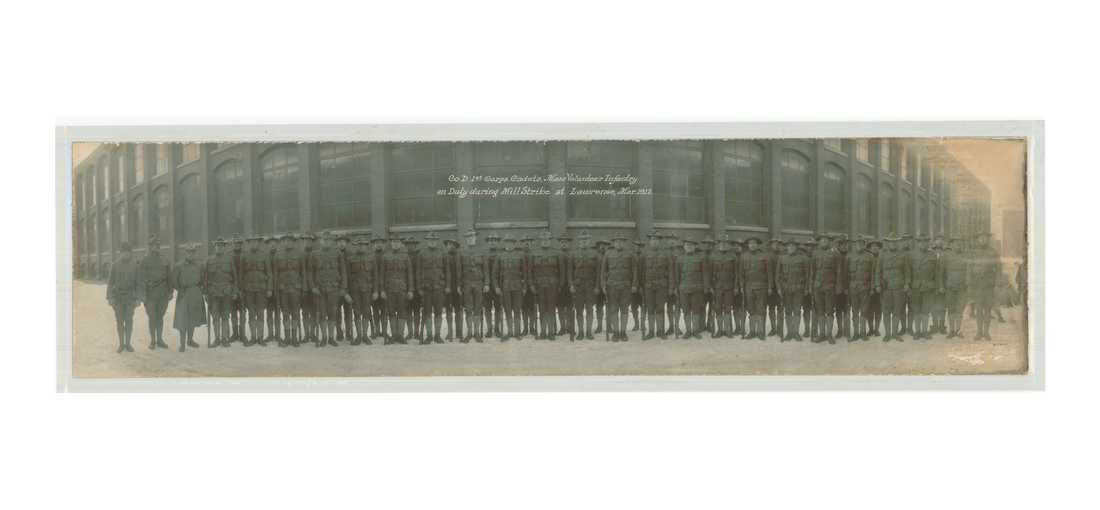

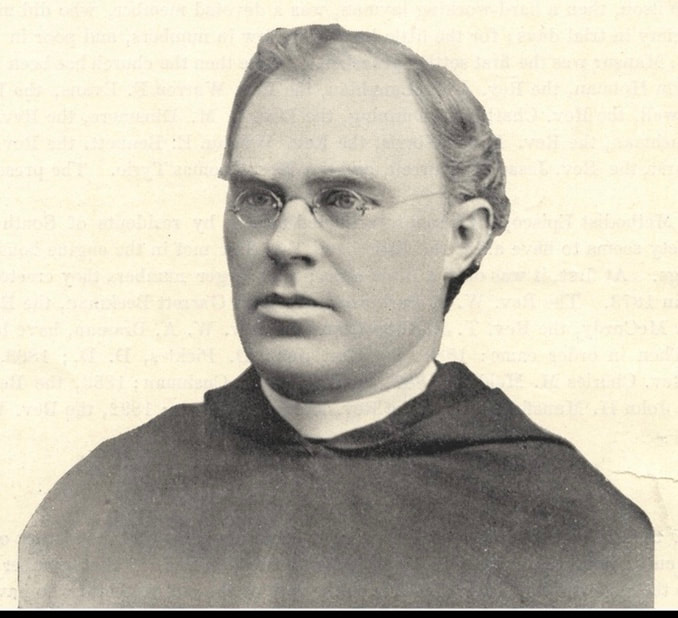

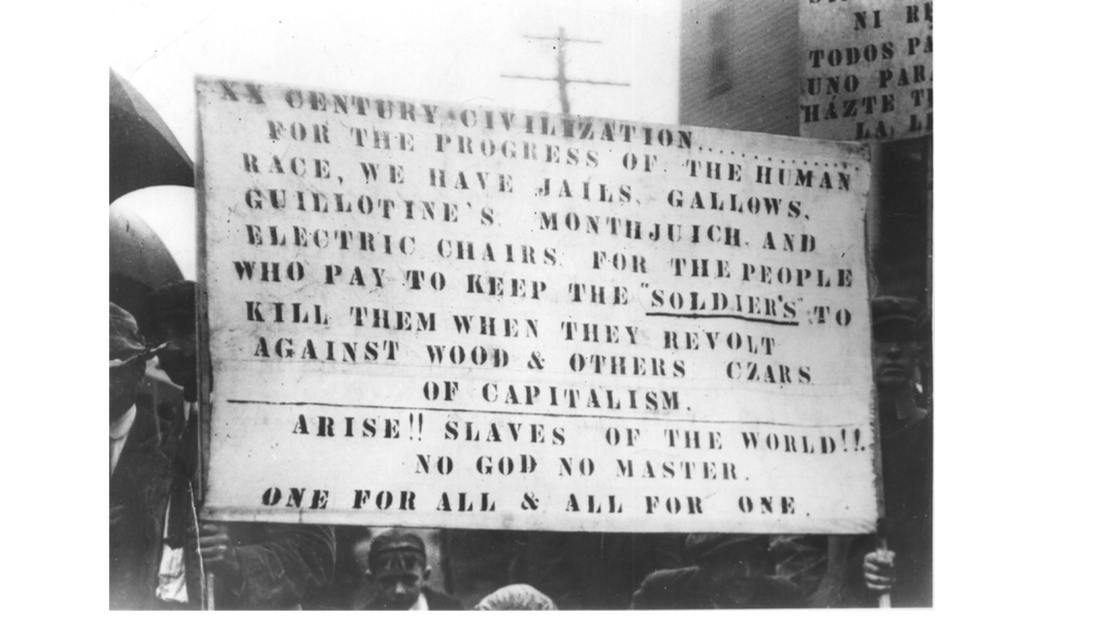

The demands of the strikers were ignored. The next day, 22,000 striking workers basically prevented non-striking workers from entering the mills, and 37 people were arrested in violent confrontations with police. This state of disruption continued for a couple weeks despite a furtive meeting between five members of the strike committee and representatives of Lawrence’s eight mill corporations. Below: Scene from the strike. Caption reads Pacific Mill watchmen turn hoses on strikers, January 15, 1912  For a few weeks, things looked like a stalemate, or war of attrition. Then there was a twist in the plot. During a clash between strikers and the police on Monday evening, January 29, Anna Lo Pizza, an Italian woman, was shot and killed. As a result of the disturbance of the day, the city council gave control of the city to the officer in command of the militia, Major Sweetser. Parading and assembling in the streets or on the common was ordered discontinued. The mayor also requested additional protection, and the governor ordered twelve companies of infantry, two troops of cavalry, and fifty police officers from the metropolitan police force to report at once in Lawrence. Below: Photo of one of the militia companies on duty in Lawrence during the 1912 strike In connection with the death of Anna Lo Pizza, the strike leaders Joseph J. Ettor and Arturo Giovannitti were arrested as accessories to the murder, along with the Italian worker charged directly with the murder, Joseph (Giuseppe) Caruso. Jailhouse photo of Caruso, Giovannitti and Ettor, charged with the murder of Italian striker Anna LoPizza On January 20, dynamite was found in three spots around the city, claimed to have been planted by anarchists among the strikers. Strike representatives claimed the dynamite had been planted by agents of the mills. Relief efforts were established. According to the congressional strike report, two soup kitchens were maintained by the Italians (on account of being the largest group presumably), one by the Syrians, one by the Polish, one by the Armenians, and one at the Franco-Belgian Hall for all nationalities not provided for elsewhere. “The strike relief committee investigated the cases of applicants for help to determine whether or not they were strikers, although the investigation was largely omitted in the case of the Italians, of which race practically everyone employed in the textile mills was on strike.” (emphasis added – it shows the overwhelming Italian participation in the strike.) Below: relief provided to children of strikers Despite the sidelining of Ettor and Giovannitti (who were later acquitted – see epilogue), the strike continued. By this time, the Catholic church leaders of Lawrence had gotten involved. The church in Lawrence was dominated by the Irish clergy who had built the Catholic Church in New England. There was also a large French-Canadian contingent, who had emigrated in the 1870s and 1880s. Among the Irish establishment, support was strong for the captains of order. Father Timothy J. Regan, an Irish priest at St Laurence O’Toole, served as chaplain for the militia (in part because most of the members of the militia were Irish). He would celebrate Sunday mass in the armory for the troops and their heavy-handed commander, Colonel E. Leroy Sweetser, who had led the attack on women and children when they were leaving the city on February 24. Regan praised the soldiers for “making it possible for every citizen willing and able to work to do so.” On the other hand, he did preach that owners had an obligation to ensure operators were paid adequately. This was the official posture of the Catholic church, set forth in the Rerum Novarum. (The Rerum Novarum was a papal edict from 1891 setting forth the proper relationship between labor – to work and obey – and capital – to provide.) In gratitude for his service, two military companies presented Father Regan with a "handsome and costly pair of gloves" and a shaving set. And at French-Canadian St. Anne’s, an unidentified priest told the press, "we have done everything to educate the people to obey the laws and customs of this country ... we knew nothing of the strike until it was upon us. Our congregation will go back to work." And Father Joseph W. Dreyer, a priest at the church, after reading portions of Rerum Novarum in his Sunday sermon, exhorted his parishioners to return to the mills. Contrast these pro-management responses of local Catholic priests with the response of the head priest of the Italian parish, Holy Rosary, named Mariano Milanese. His role in the history of Holy Rosary church is covered in another blog post. “The priest whose pro-strike comments and policies seemed to garner the most attention was Mariano Milanese. The Italian-born pastor of Holy Rosary parish had come to Lawrence in 1902 specifically to establish a church for Italians. Possibly more attention was paid to him than other priests because Italians, the largest immigrant group, were the backbone of the strike and provided local leadership. In addition, his church was located opposite the Everett Mill in the center of the turmoil. When Milanese was unsuccessful in persuading mill agents to raise wages, he read a letter to his congregation from William M. Wood, president of American Woolen, the city's largest mill. Although Wood asked the operators to return to work with the understanding he would increase wages when he could afford to do so, Milanese told his congregation their stand was correct. He would support them to the full extent of his powers and he then began to solicit funds for relief.” (James J. Kenneally, Catholic Clerical Quandary: The Lawrence Strike of 1912 in American Catholic Studies Vol. 117, No. 4 (Winter 2006)) Below: Father Mariano Milanese of Holy Rosary Church, the Italian congregation founded in 1904. Of the Catholic clergy, he was most sympathetic to the strikers, who were mostly Italian. By mid-February 1912, a more official Catholic response in Lawrence had been formulated by its Irish leadership. It was decidedly anti-strike. Father James O'Reilly, head of St. Mary’s and de facto head of all the Catholic churches in Lawrence, organized a public campaign against the dangers of socialism which nearly everyone equated with the IWW. On Sunday, February 25, pastors of three of the Irish churches criticized that doctrine. In a coordinated exercise, at different masses at St. Laurence, Regan asserted, "socialism, anarchy, agnosticism, and atheism are at our very door and must be fought". Meanwhile, Father McDonald at Immaculate Conception denounced socialism as the greatest enemy of the church and the world, and called upon Catholics to do their utmost against it. Then Father O'Reilly, at St. Mary’s, in a widely publicized sermon, asserted that the evils of socialism transcended the labor issues. Below: Father James O'Reilly, head priest of St. Mary's and head of the Augustinian order in Lawrence Despite these official church messages, however, Father Milanese continued his citywide appeal for strike funds, stating he was helping two hundred people a day. Father Milanese’s relief efforts, along with other church relief programs, had the effect of undermining reliance on IWW assistance. As Milanese observed, many parishioners were ashamed to go to the IWW strike committee for food and money; they certainly were not encouraged to do so by him. Other churches also held special collections and solicited contributions to the St. Vincent de Paul Society to assist strikers. Cardinal O'Connell contributed two hundred dollars to Milanese's fund. Yet Italians, often led by Rocco, had to go to the basement of St. Anthony's, the Syrian church, to meetings where they heard Ettor address them in their native language. He and any other Italian strike leaders were barred from Holy Rosary. Nevertheless, Rocco, never criticized Milanese. Milanese also often visited strike leaders Ettor and Giovannitti when they were jailed in the shooting death of Italian striker Anna LoPizza and supplied them with literature during the months they were incarcerated. Outcome of the 1912 Strike Upon the arrest of Ettor and Giovannitti, the IWW replaced them with Big Bill Haywood and other leaders, who worked with the multi-ethnic strike committee in Lawrence. As a result of the political backlash caused by reports of police attacking unarmed women and children, politicians in Massachusetts and Washington, D.C. began to clamor for some kind of settlement of the strike. Victory for the strikers was achieved on March 12, 1912, when all their demands were met. Below: Strikers voting to accept the strike terms, Lawrence Common, March 14, 1912 Epilogue - Continued IWW Struggle for Justice in Lawrence, Led by Italians for Italians Until Ettor and Giovannitti were set free, organizers had unfinished business. From April to October 1912, an unprecedented amount of activism occurred in Lawrence. Massive street marches, counter marches (the God and Country parade), violence, funerals. Much of this post-strike history seems to be forgotten in Greater Lawrence these days. Labor activist Carlo Tresca – who apparently did not speak English – was sent to Lawrence to address workers on May 1, so-called May Day, the international day of the worker. Tresca was a leader not only in the I.W.W. but also in the Federazione Socialista Italiana del Nord America (the FSI). His young Irish-American lover, Helen Gurley Flynn, had already been working in Lawrence for a number of months organizing workers. The activism was as much about Italian national pride as it was about worker solidarity. For this reason, the IWW were careful to choose an Italian organizer. “Although they never appealed to nationalist sentiments, FSI leaders understood that the agitation to liberate Ettor and Giovannitti was as much an ethnic conflict as a labor/political struggle. Leadership of the Italians therefore had to be entrusted to someone who commanded great respect among Italian workers, and who possessed exceptional talent as a strategist, agitator, and organizer. The man best qualified for the task, the FSI knew, was Tresca.” (Pernicone book on Tresca) “The Lawrence May Day parade attracted…5,000 members of the IWW, mostly Italians, including many women carrying infants and pushing baby carriages. A large rally was also held at the Essex County Jail on Hampshire Street, where the prisoners [Ettor and Giovannitti] were held, and later than evening Italian members of Local 20 conducted their own procession.” (Source: Pernicone) Below: Italian organizer and orator, Carlo Tresca. He arrived in Lawrence a month after the strike to try to maintain the revolutionary momentum of the strike to further organize the workers. He spoke no English, only Italian. The next mass protest was on Sunday, May 26, 1912, when the IWW conducted a funeral parade in honor of fallen workers Lo PIzzo and Ramey. Some 15,000 workers from Lawrence, Haverhill and other industrial towns participated. (Source: Pernicone) Photo: Demonstrators laying a wreath on the grave of fallen striker Anna LoPizza, Memorial Day 1912, more than two months after the strike ended To prevent further disturbance, the City prohibited demonstrations by the I.W.W. on public property. Tresca was not thwarted.

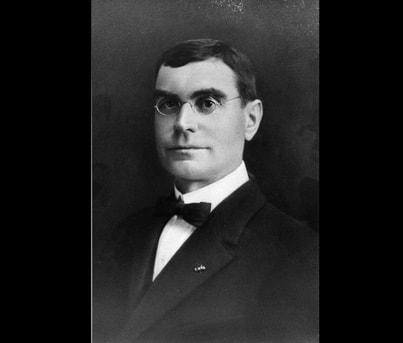

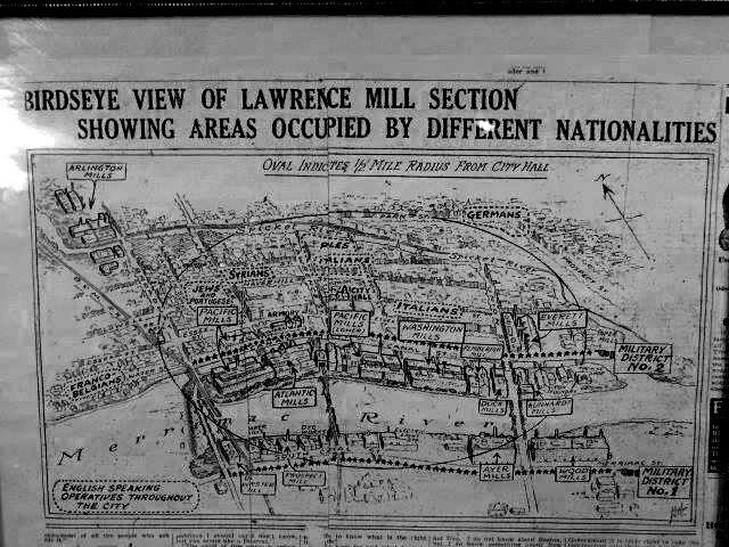

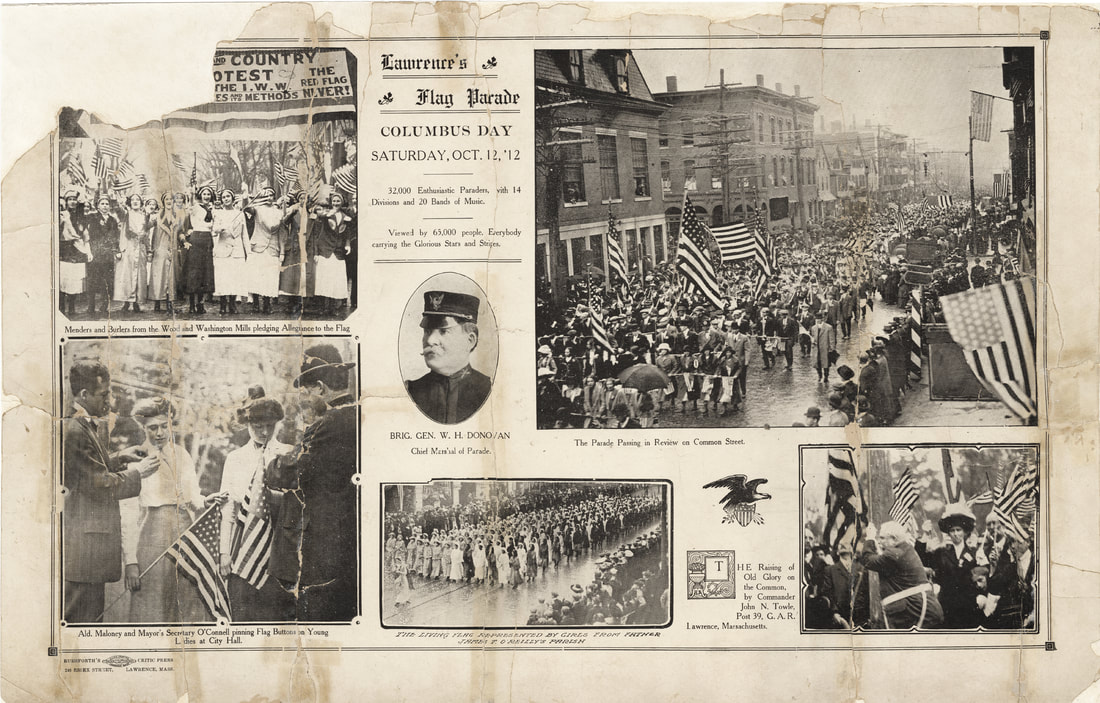

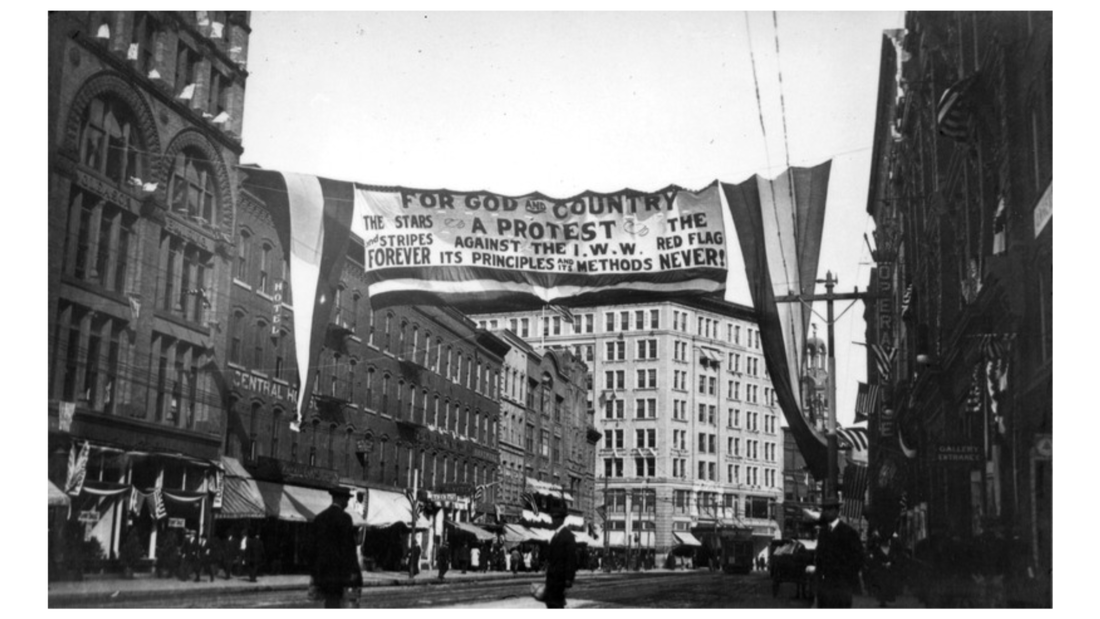

Tresca then approached prominent Italian-American banker Fabrizio Pitocchelli for money to support future demonstrations. “Reminding Pitocchelli that many of his Italian clients were IWW members, Tresca offered him a choice: provide money or face a boycott of his bank. A promise of money was immediately forthcoming.” (Source: Pernicone) On Sunday, September 24, a large rally of workers from Haverhill, Lynn, Lowell, New Bedford, Fall River and other industrial towns converged on Boston Common – 20,000 to 35,000 in all. (ibid). There, Bill Haywood called for a General Strike. However the next day, Ettor and Giovannitti sent letters urging workers not to engage in a general strike, because “the risk of failure was too great on the one hand and the temper of the workers, particularly the Italians, too explosive on the other.” In the meantime, the followers of Lynn-based anarchist, Luigi Galleani began to jockey to take control of the situation from Tosca. Rejecting even syndicalist unions as instruments of social struggle, Galleani placed his faith in all methods of revolutionary violence, including bombs and assassination. Thus, despite the call from Ettor and Giovannitti not to hold a general strike, on September 26, the anarchist leaders took up positions outside the mills and urged Italian workers to strike later that day. “By 3:15 p.m. on September 26, 1912, the Italians began streaming out of the mill, soon to be joined by Italians from the Washington Mill. At a large meeting at Lexington Hall that evening, the IWW and the Italian anarchists vied for leadership of the assembled crowd. Spurred by the exhortations of the anarchists, the Italian workers en masse voiced their desire for a general strike. The following morning, September 27, several thousand angry Italians abandoned the mills. Their belligerent mood quickly proved infectious, and some 10,000–12,000 workers went on strike the next day.” Below: Luigi Galleani, Italian anarchist and rival to the IWW, His followers also worked to agitate the Italian workers of Lawrence in the months after the strike SIDEBAR: Who were the Galleanists? They were a radical anarchist group that followed the teachings of Luigi Galleani, based in Lynn, Mass. Starting in 1917 when they came under increased government supression, they followed a path of violence. "It was in April of [1917] that the United States entered Word War I, to which Galleani and his followers were uncompromisingly opposed. This brought down upon them the full panoply of government repression. Throughout the country their Clubhouses were raided, men and women beaten, equipment smashed, libraries and files seized and destroyed. Their lectures and recitals were disrupted, and their newspapers and journals suppressed, among them Galleani’s Cronaca Sovversiva (the Subversive Chronicle), in which he denounced conscription and the war. The Galleanists viewed these developments with mounting indignation. Men of energy and determination, they could not stand idly by while their comrades were being imprisoned, their presses silenced, their meetings disrupted and dispersed. An overwhelming desire to retaliate, to strike back at the state that was stifling and crushing their movement, took possession of them. So it was that between 1917 and 1919, the height of the Red Scare, a group of anarchists came into being whose function was to carry out bombings. Sacco and Vanzetti were among them. They refused to turn the other cheek. Uncompromising militants, they rejected docile submission to the state. They were determined, on the contrary, to answer force with force, not only as a matter of self/defense but of principle and honor. The climax was reached in 1919, following a rash of anarchist deportations. Among those evicted from the country was Galleani himself. This proved the last straw. The Galleanists issued a leaflet threatening retaliation. “You have shown no pity to us,” it declared. “We will do likewise. And deport us! We will dynamite you! ” An enemies’ list was drawn up, to whom package bombs were sent in the mail. This occurred on the First of May, the premier working class and anarchist holiday. The list consisted of 30 names, including Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson, Secretary of Labor William B. Wilson, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Commissioner General of Immigration Anthony Caminetti, and US. District Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, as well as John D. Rockefeller, and P. Morgan, among others. Each of the intended victims had antagonized the Galleanists in some unforgivable way: arrested their comrades, closed down their newspapers, deported them to Italy, and the like. Additional bombs were delivered by hand to the doors of intended recipients. None of them was hurt, although the house! maid of one had her hands blown off and an elderly security guard was killed. To men of the bombers’ stamp, the use of violence was not a crime; it was a justifiable response to persecution. They considered themselves at war with the forces of government, and if they resorted to bombs it was as the government used bombs, for the purpose of war. Violence, in any event, was one of the few weapons at their disposal, a necessary means of self—defense. How else were they to retaliate against their tormentors?" Above: The Scandalous Protest Sign Declaring No God, No Master - Lawrence, Mass. Sept. 1912 To regain the upper hand against the followers of Galleani, the IWW organized another memorial parade on Sunday, September 29. That afternoon, “in defiance of the police and a torrential rain, 4,000 workers—most of them Italians—marched silently to the [St. Mary Immaculate] cemetery, with Tresca at the head, standing backward in a one-horse buggy. Tresca remembered that “one big banner, when all the others had given away to the force of the persistent downpour, remained intact. On it was a red, challenging motto, ‘No God, No Master.’ Above: Lawrence's Mayor, Michael A. Scanlon This message proved to be the last straw for business and church leaders in Lawrence. “Major Michael A. Scanlon called upon all the “patriotic and law abiding citizens” to wear American flag buttons in their lapels as a rebuke to the advocates of anarchy and atheism who had invaded their God-fearing city.” At a meeting in City Hall, Father James O’Reilly, the Catholic priest who was the most powerful man in Lawrence, shouted: “Those who do not want to work better take a hint and go. We will drive the demons of anarchism and socialism from our midst.” More than 100 private detective and thugs were hired, and were put to use during the 24-hour hour protest strike that took place on Monday, September 30 involving 10,000 workers. It became dangerous to wear an IWW pin. Below: An IWW pin of the kind that got Jonas Smolskas killed in October 1912 “To demonstrate that neither he nor the IWW could be intimidated, [Tresca] planned an act of defiance…on October 5. With his friend Bertrando Spada, one of the FSI’s foremost leaders, armed and walking behind to cover his back, Tresca strolled conspicuously up and down Essex Street wearing an IWW button in his lapel and secreting a revolver in his pocket, almost daring the detectives he encountered along the way to start trouble. None stepped forward to challenge the “Bull of Lawrence,” as he had come to be known.” However, on October 19, 1912 Lithuanian immigrant Jonas Smolskas was assaulted for wearing an IWW pin, and died three days later from his injuries. Below: Alleged photo of Jonas Smolksas. By the way, in this blog post, I'm not saying other ethnicities did not participate in the strike. The most noteworthy aspect of the strike was that over forty nationalities, the members of which spoke little English, coordinated their efforts so successfully. Rather, in this blog entry I point out that the strike was "Italian" insofar as (1) the significant majority of strikers were Italian immigrants, (2) and so were the majority of the strike leaders. I would suggest that one reason for this participation and leadership was the prevalence, at least at that time, of radicalism in the Italian immigrant community. Above: Map printed during strike showing locations of ethnic neighborhoods - Italians, Poles and Syrians concentrated in most densely populated area of tenement housing A few days before the death of Smokskas, on Columbus Day, October 14, 1912, “around 30,000 people assembled for the “God and Country” parade. A celebration of American patriotism and antiradicalism, the parade had no place for the hated IWW, and any marcher sporting an IWW button or banner was to be arrested. No manifestation of ethnic loyalty other than American was tolerated, a reflection of the Anglo-Saxon and Irish hostility to “foreigners,” which had been evidenced throughout the strike and defense campaign. Below: Scenes from Lawrence's anti-radical anti-IWW flag parade, held Columbus Day 1912. Source: Louise Sandberg's Queen City archive blog. "The display of Italian flags was expressly forbidden, the national origin of Columbus notwithstanding! Most of the marchers were children from public and parochial schools, municipal employees, members of American patriotic societies, Catholic associations, and some representatives of the AFL. Not more than 4,000 mill operatives participated in the parade, according to I.W.W. organizer Bill Haywood, although it is very likely that many more were bystanders who had turned out to observe a holiday parade but did not subscribe to the anti-IWW objectives it was intended to promote. The IWW, meanwhile, had tried hard to dampen popular enthusiasm for the parade by explaining to the workers, the majority of whom were Catholics, that the IWW had never taken a position against religion, and that the issues of religion and patriotism were being exploited by city officials and mill owners in order to destroy the union. But the IWW’s disclaimer did not succeed in rallying support. Only 4,000–5,000, out of an expected 10,000, showed up for the IWW’s counter-celebration at the picnic grounds in Pleasant Valley.” (Source: Pernicone). It figures, Pleasant Valley at the time was home almost exclusively to Italians. Below: God and Country Banner during the anti-IWW march, October 1912. In the end, pro-American, pro-church, pro-establishment sentiments were victorious over radicalism in Lawrence. The acquittal of Ettor and Giovannitti on November 26, 1912 removed a cause for the radicals, and calmed a lot of people down. Momentum was lost and the IWW failed to organize workers into a permanent union in Lawrence. The history of the IWW in Lawrence is covered in my blog post about the 1919 strike, which everyone in Lawrence seems to have forgotten about but which was just as important as the 1912 strike. By that time, however, the IWW had become unpopular for its opposition to World War I.

Also, the more radical Italian leaders, such as the followers of Galleani, scared the bejesus out of most Americans after they launched their terrorism campaign in 1917. Italian activism subsided just as new immigration rules took off, which led both to the deportation of a lot of the Italian radicals and the end of Italian immigration by 1924. Also, the experience of World War I had made many Italians more patriotic and focused on nationalistic issues rather than class issues, at least on the international political stage. Furthermore, the longer Italian immigrants stayed, the more economically successful they generally became. Because of these trends, from the mid-1920s onward, the story of Italians in Greater Lawrence largely became one of making a place for themselves and making the area a better place. Below: Italian-American fraternal organization, Lawrence, Mass. 1925

1 Comment

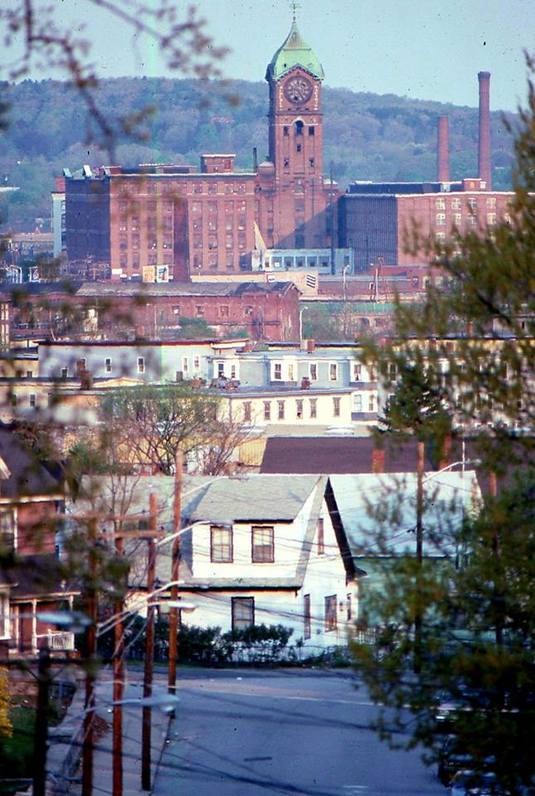

The Ayer Mill Clock Tower hovers above Lawrence, mid 1980s. Photo by Butch Fontaine.

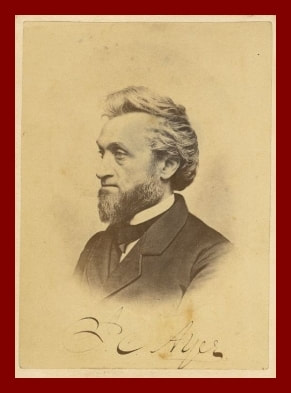

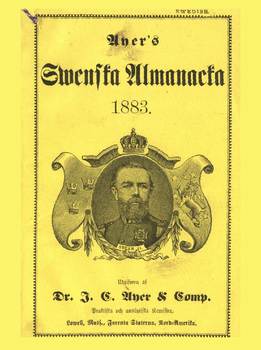

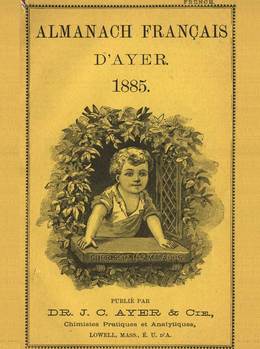

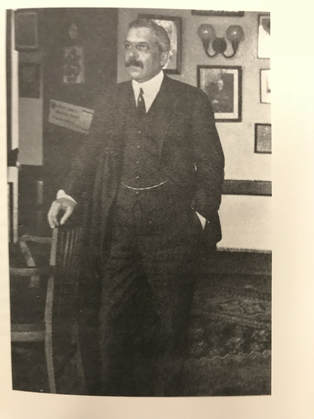

The Ayer Mill Clock Tower as a landmark There aren’t many landmarks left for a Lawrencian to point to. The beautiful post office? Demolished. The grand old police station? Demolished. “Theater Row” where many mill workers and their children watched the latest Hollywood talkies? Gone. Department store Sutherlands and the other large retail establishments of Essex Street? Gone. Also gone are many nice churches and schools, and even whole neighborhoods demolished for “urban renewal”. Most of the surviving Lawrence landmarks are industrial: the Great Stone Dam that made the whole place possible; and the mills lining the river and canals – the Pacific, the Wood, the Everett, etc. About half of the old mill buildings have been demolished. By far the most prominent landmark left in Lawrence is the clock tower of the Ayer Mill, now a New Balance factory. The tower rises 276 feet and is visible from many parts of the city, as well as from Interstate 495 passing by on the elevated roadway. It is the biggest mill clock tower in the world. As we all know, its clock face is only six inches smaller than the one on Big Ben. After decades of neglect the clocktower was restored in 1991 and has been maintained ever since. Below: Video of New Balance factory in Lawrence, Mass. This blog post tells the fascinating life story of its namesake, Frederick Ayer, peddler of patent medicines and almanacs who diversified into textiles. After you read it, maybe you’ll start calling the Ayer Mill clock tower “Big Fred”. Frederick’s background Practically every person in this country with the last name of Ayer – including my great grandmother Mildred Ayer – is descended from the original American Ayer [or Ayre or Ayres], named John. He was born in 1582 in Salisbury England and was a founder of Haverhill, where he died in 1657. John Ayer was Frederick Ayer’s fourth great grandfather, making Frederick a Haverhillite of sorts (and my sixth cousin five times removed). However, three generations earlier his family had moved from Haverhill to the coast of Connecticut. Frederick was born in Ledyard Connecticut, near New London, in 1822. Below: Frederick Ayer late in life. Source: Wikipedia His Brother James Cook Ayer and Ayer’s Patent Medicines For the early part of his life, Frederick followed in the shadow of his older brother, “Dr.” James Cook Ayer, born 1819. James studied medicine, apparently in Philadelphia, and may or may not have become a proper doctor. He did however become an extremely successful proprietor of patent medicines. James started practicing as a pharmacist in Lowell in 1841 at age twenty-three. His uncle lent him the money to buy his original pharmacy in Lowell. He settled there because his mother, a Cook, was from the Lowell area. He was a graduate of Westford Academy in neighboring Westford, Mass. Below: "Dr." James Cook Ayer, from his 1874 congressional campaign While a pharmacist James began developing cures for his customers’ ailments, and soon founded J.C. Ayer & Company. His five major products were Cherry Pectoral (“cure-all”), Cathartic Pills (laxative), Sarsaparilla (cure for syphilis and other “blood disorders”), Ague Cure (anti-malaria), and Hair Vigor (against thinning hair). Cherry Pectoral was by far his most popular and profitable product. Its popularity was possibly aided by three grams of opium in every bottle. In 1859, the company built a facility at 165 Market Street, Lowell, which they later expanded. By 1865, Ayer employed 150 people. In one year the factory processed 325,000 pounds of drugs, 220,000 gallons of spirits and 400,000 pounds of sugar. Below: Ayer's Cathartic Pills. Source: Cliff Hoyt website (http://cliffhoyt.com/jcayer.htm) Ayer’s Almanac James distinguished himself from other quacks – um, I mean doctors – by means of extensive advertising. In 1851, he hit upon the idea of providing a free almanac to all his customers. Almanacs were already essential household items, offering a range of helpful information for the current year – from public holidays to suggested planting times to town directories to historical summaries. However, James also peppered his almanac with advertisements for his products. Print production of Ayer’s Almanac is estimated to have exceeded 16,000,000 and was possibly as high as 25,000,000. The J.C. Ayer Company’s modest slogan for its publication was ‘Second only to the bible in circulation.' The almanac was eventually published in twenty-one different languages, reflecting the burgeoning immigrant population of the last decades of the nineteenth century. Below: Examples of foreign language copies of Ayer's Almanac (Source: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/almanac/heyday.html) James looked for a marketing opportunity wherever he could find it. For example, during the Civil War when Congress allowed postage stamps to become legal tender due to a shortage of currency, James encased stamps in miniature advertisements to protect them from wear and tear but also market his brand (source: www.cliffhoyt.com/encased_postage.htm). Below: Encased postage stamps bearing J.C. Ayer insignia (Source: Cliff Hoyt website http://cliffhoyt.com/encased_postage.htm)

Above: Advertisement for Ayer's Sarsparilla. Source: NIH website

Transition of The Medicine Business to Frederick; James’ Business and Political Pursuits; His Untimely Death In 1855, James offered his brother Frederick a partnership, and ceded day-to-day operations to his younger sibling. He started to become a man of wealth and leisure, traveling on extensive tours. In 1865, he purchased a statute on a trip to Germany and presented to the City of Lowell. This “Winged Victory” statue still stands today in Monument Square in front of Lowell City Hall. Below: Victory Statue, Monument Square, Lowell (Source: Wikipedia) By the 1850s, he was looking for investments for his enormous profits. However, he seems to have been the “dumb money” that came in late – in 1857, he lost $2 million dollars when the Bay State mills in newly founded Lawrence went bankrupt. That was an enormous sum of money in those days. Later, in his book Some of the Uses and Abuses in the Management of Our Manufacturing Corporations, he complained of the ways in which shareholders like him were denied a voice because entrenched management controlled the governance apparatus of corporations. Basically, he said, the insiders rigged shareholder elections. These days, someone like James C. Ayer is called an activist shareholder. In the book James launched an attack on the firm of A. & A. Lawrence, the powerful firm founded by brothers Abbot and Amos Lawrence, consummate Boston Brahmins and benefactors of great cultural institutions. (Lawrence, Mass. is named after Abbot Lawrence.) I take this as an indication that the Ayers were outsiders, not connected to the commercial elite of Boston, such as the Lawrences, with their ties to Harvard and Unitarianism (you know, “Cabots talking to Lowells and Lowells talking to God” and all that). This observation helps explain Frederick Ayer’s very unusual decision, in 1886, to allow the swarthy Portuguese immigrant’s son, William Wood (a.k.a. Guilherme Madeira), to run his textile empire and marry his daughter. More on that below.

Ayer, Massachusetts (formerly a section of Groton) was set off and named after James Ayer in 1871 when he paid for the new town’s city hall. He had dreams of becoming an important public figure. In 1874, he ran for Congress and was heavily defeated. He was so unpopular, the citizens of Ayer even burned him in effigy. This was apparently too much for his ego to handle. He went mad, spending a number of months at a private insane asylum in New Jersey. James died in 1878, leaving his brother Frederick to run the family business empire for another forty years until his death in 1918.

Below: The Town Seal of Ayer, Massachusetts, named after James Cook Ayer Frederick Ayer Takes Over In 1878, Frederick was fifty nine years old and a millionaire many times over thanks to the patent medicine business. However, by this time he had embarked on his second act: textile magnate. After a number of setbacks – and the loss of stupendous amounts of money as his family’s mills in Lawrence kept going bankrupt – he managed to get a handle on matters by hiring William Wood of Fall River to run the businesses. The relationship began in 1886 when Ayer met Wood while the latter was selling shares to a new mill he wanted to build in Fall River. Instead of investing in Wood’s mill, he hired Wood to help run Ayer’s mill in Lawrence, the Washington Mill. One thing led to another, and within a few years Wood was making $25,000 a year (up from his original pay of $204 a year) and he had married Frederick Ayer’s daughter. Below: Frederick's Son-in-Law, William Madison Wood, 1914 (Source: McClure's Magazine) As William Wood’s biographer wrote of the 1888 marriage between William Wood, age 30, and Ellen Wheaton Ayer, age 29:

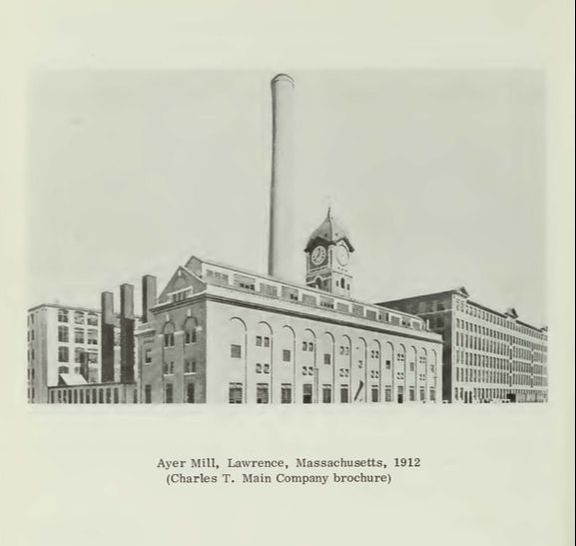

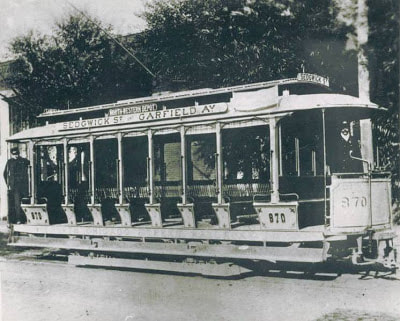

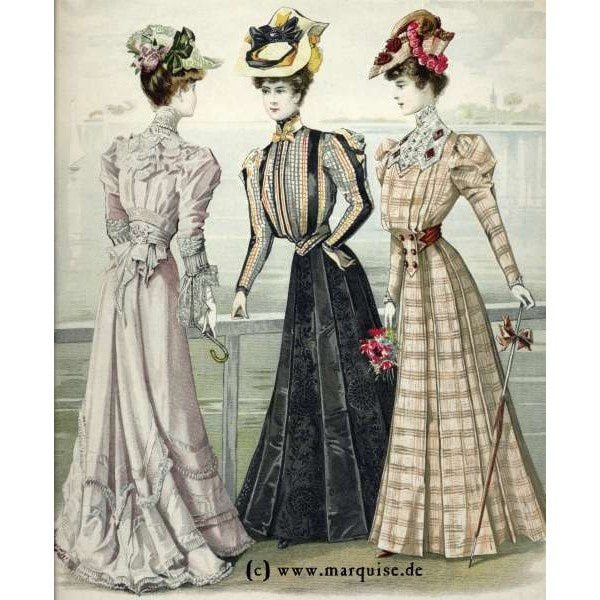

in addition to his involvement in patent medicines and textiles, Frederick Ayer was a founding director of the New England Telephone and Telegraph Company, serving in that role from 1877 to 1896. He was also a founding director of the Lowell & Andover Railroad, a subsidiary line of the Boston & Maine, serving from 1873 to the time of his death. (Source: his New York Times obituary, March 15, 1918.) Below: The Frederick Ayer Mansion, 357 Pawtucket Street, downtown Lowell (Wikipedia) Above: Brochure for the Ayer Mansion on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston Frederick Ayer was President of the American Woolen Company until June 1905, when he retired at the ripe old age of 83. Keep in mind that Ayer was still having children (with his second wife after the first one died) as late as 1890, when he was sixty eight! Frederick Ayer lived to be 95, passing away in 1918 in Thomasville, Georgia, known as “Yankee’s Paradise” for the number of northern industrialists who had winter homes there. One of James’s daughters married George Patton, the famous American commander in World War I. In 1909, William Wood honored his father-in-law by naming his most architecturally prominent mill after him. Below: Illustration of the original Ayer Mill complex from a company brochure, 1912 The Ayer Mill The following is a description of the Ayer Mill in a wonderful study of the architectural heritage of the lower Merrimack Valley by Peter Molloy (published 1978 by the sadly now defunct Merrimack Valley Textile Museum): “The Ayer Mills were designed by Charles T. Main Architects and built for the American Woolen Company as that firm's third worsted mill in the city of Lawrence. The mill was named for Frederick Ayer, a Lowell patent medicine manufacturer and the father-in-law of William Wood, the President of the American Woolen Co. The Ayer Mill manufactured worsted suitings and every operation in worsted manufacture was accomplished within its two mill buildings and dye house. An underground tunnel connected the Ayer to the Wood Mill, which was situated within 200 feet of the Ayer. During the 1950s the American Woolen Company ceased operations, and the Ayer Mill was tenanted to a number of small concerns. The dyehouse and boiler-turbine house were destroyed to create a parking lot. The boiler-turbine house contained eight 600 HP boilers and two 2. 5 MW turbo-generators. The dyehouse was 2 stories, brick, 90' x 126'. Of the two remaining mill buildings No. 1 is brick, 6 stories in height, 123' x 595'; No. 2 is 7 stories, brick, 123'x329'. The 2 mills are connected at the east end by an 8 story building, 40'x81', which contains water closets and stairways. Another building, 40'x81', connects the west ends of mills 1 and 2. This building was used as a stair and elevator tower. Above the roof level of this building rises a 40' x40' brick tower, the weather vane of which is 267' above street level. In the tower was a 20,000 gallon water cistern, a bell, and a clock with 4 illuminated dials each 22' 6" in diameter. The buildings were decorated with elaborate facades in a neo-Georgian style, with pediments, granite coursings, and Palladian windows. The buildings are among the most highly styled 20th century mills in the United States. In 1910, the mill's first year of operation, it contained 75 worsted cards, 80 combs, 45,000 spindles, and 320 broadlooms. It employed over 1,000 workers. Although situated near the Essex Company's South Canal, the Ayer did not utilize water turbines, but it did use water from the canal for process and boiler water.” Below: Frederick Ayer grave, Lowell, Mass. (Source: Find A Grave)(Note the famous "Ayer Lion" in the Lowell Cemetery is James's grave) Everyone in the Greater Lawrence area seems to know the story of the Bread and Roses Strike of 1912. It stands out for two reasons:

Below: Lawrence strike announced in the New York Times, February 3, 1919 How things had changed between 1912 and 1919 Even though the 1919 strike occurred only seven years after the 1912 strike, the world had changed in ways that made a successful strike of this kind more difficult.

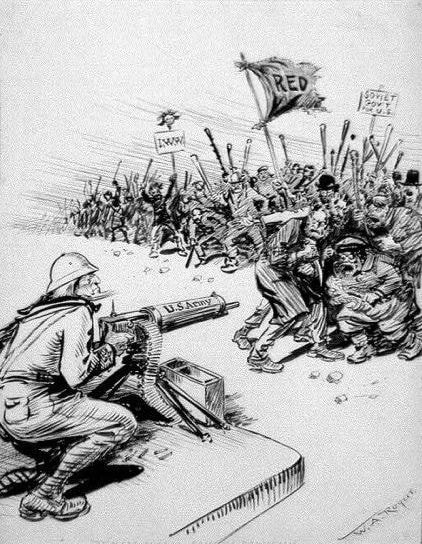

Below: The I.W.W. Charter, which reads in part "The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of the working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life." The Empire Strikes Back: The Red Scare and the Anti-Immigrant Political Climate H.L. Mencken summarized the political climate of 1919 in his book The American Scene. It was in sharp contrast to the climate in 1912, when unfettered immigration was widely tolerated because it fed the high demand of industry for cheap labor. “Returning servicemen found it difficult to obtain jobs during this period, which coincided with the beginning of the Red Scare. The former soldiers had been uprooted from their homes and told they were engaged in a patriotic crusade. Now they came back to find ‘reds’ criticizing their country and threatening the government with violence, Negroes holding good jobs in the big cities [until this time virtually no blacks had moved to northern cities], prices terribly high, and workers who had not served in the armed forces striking for higher wages. A delegate won prolonged applause from the 1919 American Legion Convention when he denounced radical aliens, exclaiming “Now that the war is over and they are in lucrative positions while our boys haven’t a job, we’ve got to send those scamps to hell.” The major part of the mobs which invaded meeting halls of immigrant organizations and broke up radical parades, especially in the first half of 1919, was comprised on men in uniform….” “As the postwar movement for one hundred percent Americanism gathered momentum, the deportation of alien nonconformists became increasingly its most compelling objective. Asked to suggest a remedy for the nationwide upsurge in radical activity, the Mayor of Gary Indiana, replied, ‘Deportation is the answer, deportation of these leaders who talk treason in America and deportation of those who agree with them and work with them.’ ‘We must remake America,” a popular author averred, ‘We must purify the source of America’s population and keep it pure…We must insist that there shall be an American loyalty, brooking no amendment or qualification.’ As [one writer] noted, ‘In 1919, the clamor of 100 percenters for applying deportation as a purgative arose to a hysterical howl…Through repression and deportation on the one hand and speedy total assimilation on the other, 100 per centers home to eradicate discontent and purify the nation.” “The man in the best political position to take advantage of the popular feeling, however, was Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. In 1919…only Palmer had the authority, staff and money necessary to arrest and deport huge numbers of radical aliens. The most virulent phase of the movement for one hundred percent Americanism came early in 1920, when Palmer’s agents rounded up for deportation over six thousand aliens and prepared to arrest thousands more suspected of membership in radical organizations. Most of these aliens were taken without warrants, many were detained for unjustifiably long periods of time, and some suffered incredible hardships. Almost all, however, were eventually released.” Given this climate of suspicion and hostility toward recent immigrants, a strike by unskilled workers from perhaps two dozen ethnicities in Lawrence would seemed destined to fail! Below: Anti-I.W.W. propaganda showing a machine-gun wielding doughboy holding off an unruly mob of foreigners. Opportunity for the Lawrence Immigrant Workers and the Reaction of the Authorities Opportunity In late 1918, the United Textile Workers of America (an A.F.L. union that mainly represented the skilled workers such as loom fixers) negotiated a reduction in the work-week in Lawrence to 48 hours. However, the deal not to reduce pay at the same time seems only to have applied to skilled workers. “In that climate of flexibility and accommodation it seems as if the Lawrence manufacturers, and the American Woolen Company in particular, wanted to discredit the unions altogether. At the very least they seemed to have wanted the workers to absorb the cost of the slack time of postwar reconversion.” (Source: Province of Reason, by Sam Bass Warner, Jr. (1988)) In other words, the management and the skilled workers colluded to pass the slack in production onto the unskilled loom operators by cutting their hours and their pay. The workers, sensing a déjà vu of what happened in 1912, when hours also were cut along with pay, went on strike. “On 3 February 1919, between 17,000 and 30,000 immigrant workers walked out of mills throughout Lawrence and began the ‘54-48’ strike. The strikers organized themselves among …different ethnic groups, with one leader per group. In addition, the strikers invited three pastors, known collectively as the Boston Comradeship (Anthony J. Muste, Cedric Long, and Harold Rotzel) as spokespeople. Ethnic stores and businesses supported the strikers by accepting coupons in place of cash. Meanwhile, the strikers boycotted stores that did not support the strike.” (From “Lawrence Mill Workers strike against wage cuts, 1919” by Kerry Robinson 16/02/2014; appearing on the site Global Nonviolent Action Database https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/lawrence-mill-workers-strike-against-wage-cuts-1919, retrieved February 10, 2018) Like the 1912, it was a strike of immigrants, by immigrants. “The general strike committee meets every morning in a dingy hall—the home, evidently, of a Syrian religious society [presumably the Marionite church?]. Approximately forty delegates come to this hall from the various language groups. Within its four walls, incontinently displaying faded pictures illustrating the Book of Revelation, Lawrence has formed her league of nations. That Syrian religious stronghold is vibrating with a new eloquence. New emotions, some of them powerful and portentous, are coming to unheralded expression. The hostile races are now allies.” (Source: Swing, Raymond. “The Blame for Lawrence.” The Nation magazine, April 26,1919.) Reaction The strike was dismissed by the A.F.L. as an unlawful “wildcat” strike. Therefore, the very union that negotiated the reduction in hours, the United Textile Workers, did not lead the strike. The walkout was covered by the mainstream press in hysterical terms involving “reds”, “commies” and “foreign anarchists”. The smelly, funny dressing, foreign-language-speaking strikers were seen as the vanguard of wild-eyed Bolsheviks. A Committee of Public Safety was organized, headed by Peter Carr, who had been a patrolman in the 1912 strike. He said “Lawrence is a city of 100,000 population and thirty-three different nationalities, most of whom are foreign. We feel this is a fertile field for the implanting of Bolshevist propaganda, and as American citizens it is our duty to suppress it.” (Source: Warner, cited above.) In other words, the response to the strike must be quick and fierce. Below: Photo of the Machine Gun used by Lawrence police to intimidate strikers, May 5, 1919. “The city administration of Lawrence enacted an aggressive approach against the strikers. Mayor John Hurley immediately began inviting in police from other towns. In less than a week, the city banned mass gatherings, restricted news coverage of the strikers, regulated inter-city travel, and kept the mills under constant police surveillance. After several cases of police beating strikers at the picket line and pro-mill infiltrators encouraging the strikers to react violently, the Boston Comradeship decided to join the picket line. At first, the presence of the clergymen deterred violent police action, but soon the police grew more intense. In one instance, several policemen cut off Muste and Long from the picket line, trapped them in an alley, beat them both, and arrested them for inciting a riot. A judge acquitted them a week later. On 18 February, a coalition of women strikers sent an appeal to Governor [later President] Calvin Coolidge to investigate excessive police brutality. Coolidge refused to meet with the coalition and sent a letter written by his secretary in defense of the local authorities’ actions. On 21 February, when a group of about 3000 strikers met in an open area near a garbage dump, two squads of police beat and then arrested strikers and injured several unaffiliated bystanders. The district court judge sided with the police and placed heavy fines on those arrested. After a lull in police violence, hostilities escalated again when the city received a machine gun from an unnamed source on 5 May to use against strikers. The machine gun was never used, but prominently displayed in front of the picket lines for intimidation. The next day, a group of men kidnapped two immigrant strike leaders, Anthony Capraro and Nathan Kleinman and left them beaten and disheveled in [Lowell].” (Source: Robinson, cited above) Were the immigrant strikers from southern and eastern Europe Bolsheviks, or was something else going on? A contemporary commentator from April 1919 explained the real story of the poor immigrant workers from places like Italy, Poland, the Balkans and Syria. “The fact that the strikers are foreigners divided among thirty-one nationalities, that few of them speak English or are citizens, and that some are boasting that in a short time the workers will own the mills, has been used as an argument that this is an attempt on the part of Eastern Europeans to impose upon America the fallacious economics of a misguided Russia. And in the light of this argument the hostility of the community, the shocking conduct of the police, and the obstinacy of the manufacturers are being justified. But the motives of the strike are not to be so precisely named or so conveniently dismissed. Had these foreigners swarmed to America imbued with the revolutionary spirit, and intrenched themselves in an industrial city to launch an attack, this strike would be truly a breach of hospitality. But they are here because American business demanded cheap labor, and many of them were even solicited by textile agents. For years the textile manufacturers have carried on a policy of gathering in the peasants of Eastern and Southeastern Europe to operate the looms of New England. These immigrants were distributed so that no more than fifteen per cent. of any one race were employed in a single mill, and the apportionment was dispassionately determined so that men and women racially hostile to one another worked side by side. This was to render organization impossible, and thus keep wages low.” (Source: The Nation article, cited above.) In other words, these workers were induced to come here because they would provide cheap labor, and their ethnicity and foreignness was used to keep them weak. Amazingly, the American Woolen Company, the main textile manufacturing company in Lawrence, had a direct hand in inviting such workers that they now faced at the picket line. “The American Woolen Company, which owns four of the eight Lawrence mills, posted lithographs throughout the Balkans depicting one of their factories as a magnificent edifice, a veritable palace of Midas, through one portal of which an army of ragged peasants marched, only to emerge from a neighboring doorway splendidly arrayed and bearing trophies—an unparalleled vision of instantaneous American alchemy. Unfortunately, actualities and visions are not allied. In red brick factories, one prodigious tier of glazed windows upon another, the European peasant has tended the looms and the spindles, and has received at the end of the week less than a living wage. The Lawrence manufacturer has not so much as justified the first unwritten premise of his posters; he has done nothing comprehensive to make Americans of these disillusioned immigrants.” (Source: The Nation article) I would really like to get my hands on a copy of the false advertising pamphlets, presumably published in Italian, Croatian, Serbian, Polish and all manner of other languages and distributed in poor rural regions to attract workers to Lawrence, where they would be kept in ethnic ghettos unable to organize with other groups of workers. Below: Poster encouraging immigration to America aimed at Russian Jews (if I can find something more on point, I will replace it) Return of the Jedi: Victory for the Strikers The immigrant workers, many of whom had been lured to Lawrence by suggestions of a better life by the employers against whom they now struck, triumphed over the Red Scare prejudices of the day and the direct hostility of the authorities. According to Robinson, cited above: “In early April, Governor Coolidge forced state arbitration between the strikers and the mill owners. The hearings held by the State Board of Arbitration and Conciliation lasted for nearly a month, but they did not lead to a compromise. However, these hearings marked the first time since the strike began that both sides directly communicated with each other. Seeing an opportunity to share credit for the resolution of the strike, the United Textile Workers [remember them??] reappeared in mid-May and negotiated with mill owners without the knowledge of those involved in the strike. The union secured a 48-hour work week as well as a 15% wage increase, more than the 12.5% increase the strike demanded. The mill owners accepted the terms since they were in need of workers and did not wish to negotiate with the strikers. Meanwhile, the strike had run out of funding. After weeks without monetary relief for strikers, organizers were ready to announce the strike as a failure. On 19 May, just as Muste prepared to announce the end of the strike, the mill owners called him to the conference with the UTW and explained the new agreement. Muste and the other organizers added a non-discrimination clause allowing the strikers to claim their former jobs. The mill owners accepted the conditions, and on 20 May 1919 the strike ended.” For many decades in Lawrence, from the 1920s through the 1960s, apparently nobody gave any historical significance to the 1912 strike, called the Bread and Roses Strike by some historians. However, by the time I was growing up in Lawrence in the 1970s and 1980s, and textile manufacturing was long dead and gone in the area, the following narrative became popular, not only to explain the strike but to explain the textile industry: Once upon a time, there were some greedy mill owners, who made a lot of profit by exploiting textile workers. The workers had a strike in 1912. They won. Wages increased, and inferior living standards were exposed, making living standards better for everyone. Everything was hunki-dori until after World War 2, when the greedy mill owners decided to move production to the American South where there were no unions. The mills disappeared. The end. A rousing story for sure. But I can't help but be a skeptic and a cynic. I investigated. I questioned the prevailing narrative. It turns out there are potentially a bazillion things wrong with this narrative. The problems have to do with all sorts of things: the misunderstanding of who the "mill owners" were (answer: blue-haired ladies on Beacon Hill with trust funds); the numerous strikes of the time, of which the 1912 Lawrence strike was but one (and a largely insignificant one except for its excellent immigrant participation); massive immigration from Southern Europe in the preceding fifteen years and the subsequent backlash that led to the closing of America's borders in 1920; etc. I'll save my numerous specific critiques of the Bread and Roses narrative for later blog posts. The key point I would like to make here is more basic: nobody these days who pays attention to the history of textile manufacturing in the Merrimack Valley seems to see the story right before their eyes. It is a story that explains the whole arc of the American Woolen Company, from its founding in 1899 to its ultimate demise in 1954. The lost story is this: the company basically only produced one thing, worsted woolen fabric. Miles and miles of it. Every year. For example, in 1912, the year of the strike, it produced 2 million square feet of worsted woolen cloth in Lawrence alone. And the company had production in numerous other New England cities. Fine. However, success does not come from production, it comes from sales. No matter how much production a company has, it is successful only if it can sell its goods. And who was buying most of the cloth by the early 1900s? Women. By the time the American Woolen Company was founded, the epicenter of fashion and clothing was the so-called Garment District of New York City, also known as the Fashion District, where fabric was turned into fashion. Textile companies lived and died by what they could sell there. From its inception, the American Woolen Company had its biggest sales office in New York City. In 1909, a few years after constructing the gigantic Wood Mill and Ayer Mill in Lawrence, the company constructed an impressive office in New York on the corner of Park Avenue South and 18th Street, dedicated to selling its product to the fashion houses and sweatshops of New York. Below: The American Woolen Company sales office near the Garment District, built 1909. At 19 stories, it would have been among the tallest buildings in New York at that time. Things were indeed hunki dori for a while. The strike occurred when confused immigrant workers spontaneously walked out on January 11, 1912 after their pay packets were short 3.57%. The pay was short, however, because the previous week they had worked 54 hours instead of 56 hours due to a progressive piece of Massachusetts legislation that reduced worker hours. At the end of the day, when the company acquiesced, the workers got a 15% raise and profits weren't affected. So good for them. The problem occurred later, in 1926, when fashion changed dramatically and demand for worsted wool plummeted for good. Rather than explain what happened in words, I'll illustrate: Before the decline of the Company: Women got around in this kind of transportation (a drafty open-air trolley): And they wore this kind of fashion: (warm woolen dresses that covered head to toe) Worsted wool cloth was essential. However, throughout the 1920s, the automobile was replacing the streetcar as the primary means of transportation. And automobiles had heaters, especially after the mid 1920s. Clothes could now be made of stylish light fabrics such as rayon, instead of stodgy worsted wool. So by 1926, women wore this kind of fashion instead (made of synthetics such as rayon): It would not be possible to wear such an outfit in a drafty open-air streetcar! Luckily, there was a new form of transportation, the motorcar. The automobile is ineffably linked to 1920s women's fashion, because it made the fashion possible. This is why when you see a photo of a woman in the late 1920s, wearing a skimpy synthetic dress, she is standing next to or riding in a car: without the car and its heater, she simply would not be able to get around dressed like this! Above: advertisement for aftermarket automobile heater, 1922. By 1929 with the advent of the Model A Ford, heaters were standard, along with that newfangled invention that changed mass culture, the radio. Below: typical flapper attire, made of synthetic fabrics. The monthly publication of the National Women's Trade Union League of America, an offshoot of the American Federation of Labor, noted in 1927: "Because the American woman isn't wearing those voluminous woolen garments any more, the woolen industry is suffering a hardship. An abnormally poor demand for woolen goods, coupled with a decline in raw wool prices, last year caused an operating loss of over two million dollars to the American Woolen Company, according to its 1926 annual report." In response to the massive changes in the textile market wrought by the motorcar, did the executives of the American Woolen Company respond by developing their own polyester and rayon production sites? No. Instead, they continued to produce miles and miles of worsted woolen cloth, even though demand (and prices) had dropped for good. A company can make a profit two ways: by making something that's better, newer fresher thus commanding a high profit; or making something that's cheaper, by squeezing production costs. After the loss of 1926, which put the American Woolen Company on the front of Time Magazine and arguably contributed to the suicide of William Wood, the founding president, the company henceforth pursued low costs rather than high value. Thus began the long slow demise of the American Woolen Company. It is no coincidence that the highpoint of Lawrence's population was the mid 1920s, when it was over 90,000. As jobs were reduced as a result of slowing production, workers moved away. The depression was a tough time, and the company was arguably only saved by the massive governmental orders from World War II and the Korean War for woolen cloth for military uniforms and blankets. However, demand had decreased so much and the prices for worsted wool had dropped so much, that if they wanted to stay in business at all making woolens instead of more exciting stuff, they had no choice but to chase low prouction costs for their low-value product. Hence the moves in the 1940s and 1950s to the South, followed by moves overseas. Imagine if the executives had innovated instead? However, that would have meant reinvesting the profits into new machinery, new technology, instead of paying high dividends every year on the preferred shares. Unfortunately innovation did not have the support of the trustees of the various Massachusetts trusts that owned the preferred shares on behalf of various old money families. Typically for such families, a great grandfather had originally locked up his capital - vast amounts of wealth made in the days of the clipper ship and the spice trade - into manufacturing companies that then got combined into the American Woolen Company. Rather than entrust his wealth directly to his heirs, who might squander it, it had been placed in trust. Boston is the original home of “asset management”, as it is called now, thanks to the widespread practice of locking family wealth into trusts where it would then be managed conservatively. The trustees did not see it as permissible to cut off the steady flow of dividends to their fiduciaries. (Which gets me to a tangent: in the 1970s, a small Lawrence-based textile manufacturer, Marlin Mills, that struggled on, did innovate, by inventing a warm, highly insulating, water-resistant cloth made out of recycled plastic fiber, called fleece. They marketed it under the brand Polartec, and it became the standard athletic wear used by high-end manufacturers of athletic clothing such as Patagonia, especially for cold-weather sports. Unfortunately, Marlin Mills did not bother to patent this great stuff they had invented so they could lock in long-term gain for their innovation. Instead, copycat fleece manufacturers quickly emerged, and the polartec cloth quickly became a commodity just like worsted wool had become a commodity. The company went bankrupt twice after trying to maintain production in Lawrence and now has moved production to Asia). So even if a company innovates to stay profitable, which is what the American Woolen Company should have done, it also has to take steps to protect its innovation, or it will suffer the fate of Polartec. PS: I didn't come up with this theory about the link between automobiles and their heaters, women's fashion, synthetic fabrics and the decline of the American Woolen Company. I got it from Frederick Zappalla, "A Financial History of the American Woolen Company," unpublished M.B.A. thesis, University of Pennsylvania, 1947. I have never seen this piece cited anywhere, so am not sure many other people have read it. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed