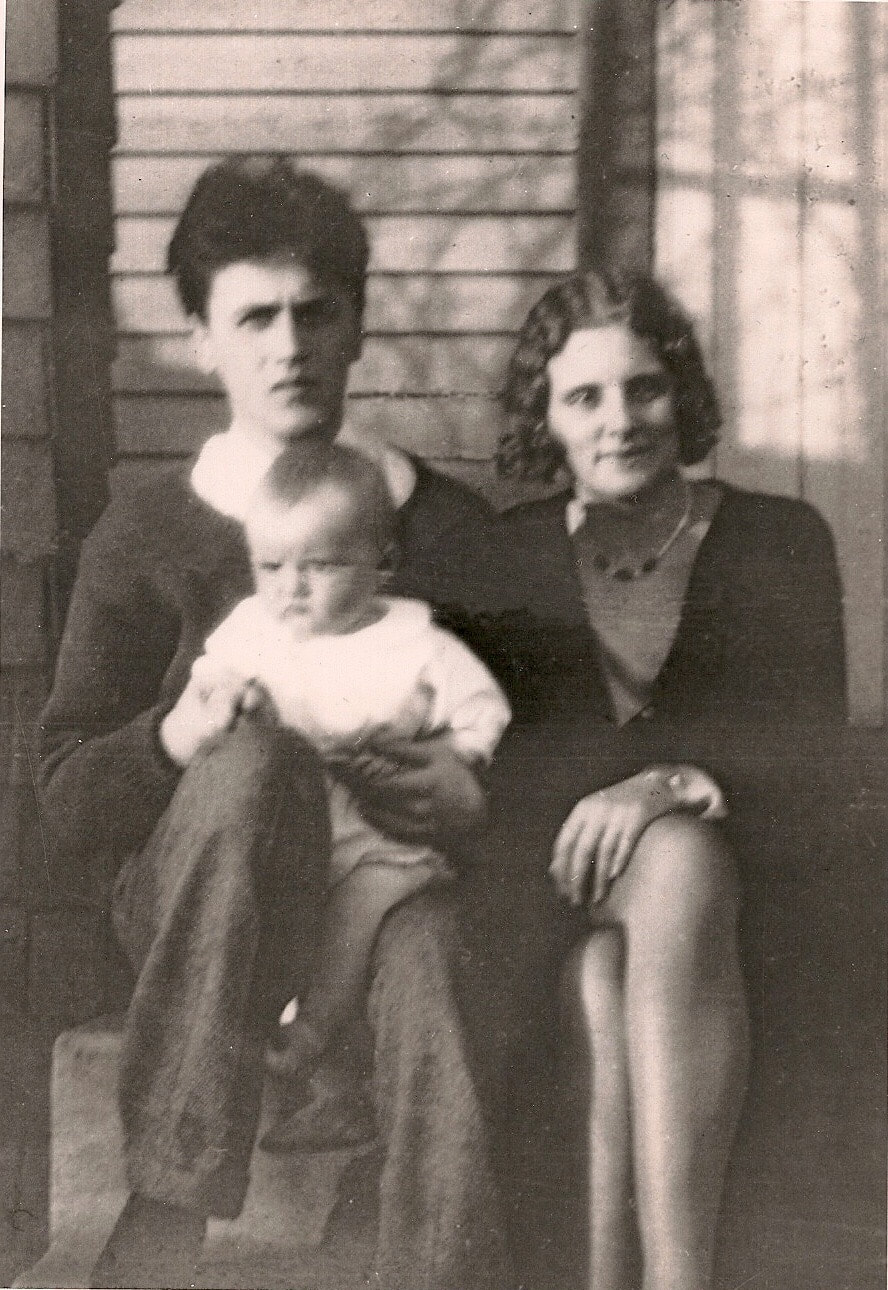

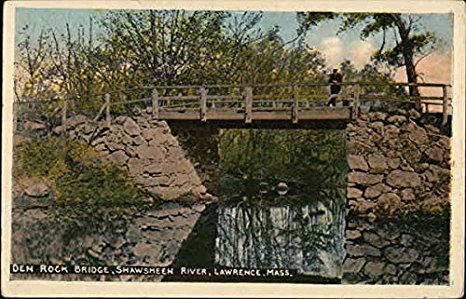

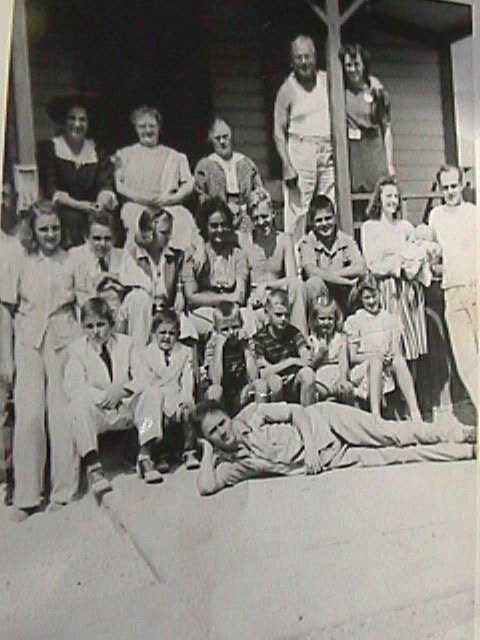

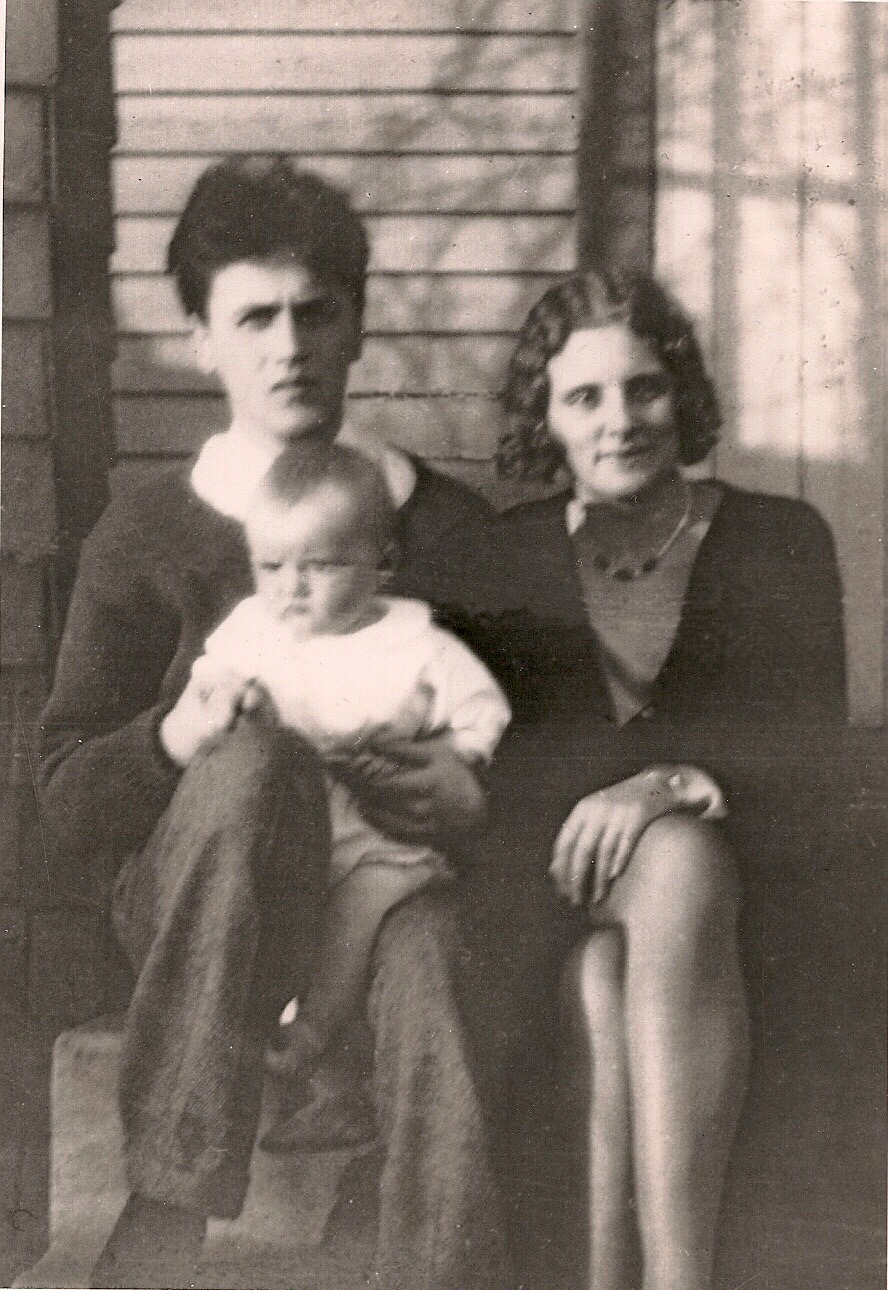

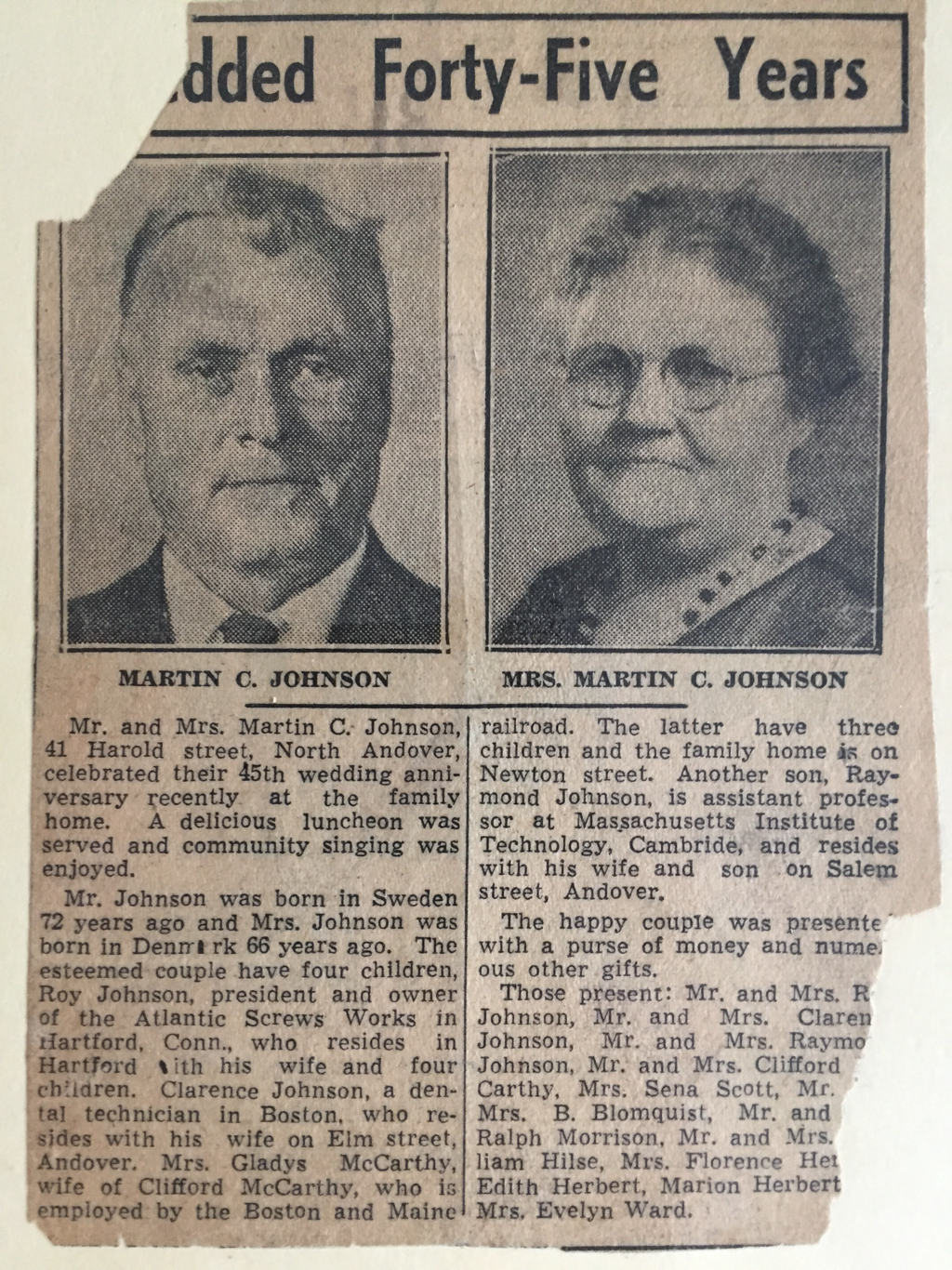

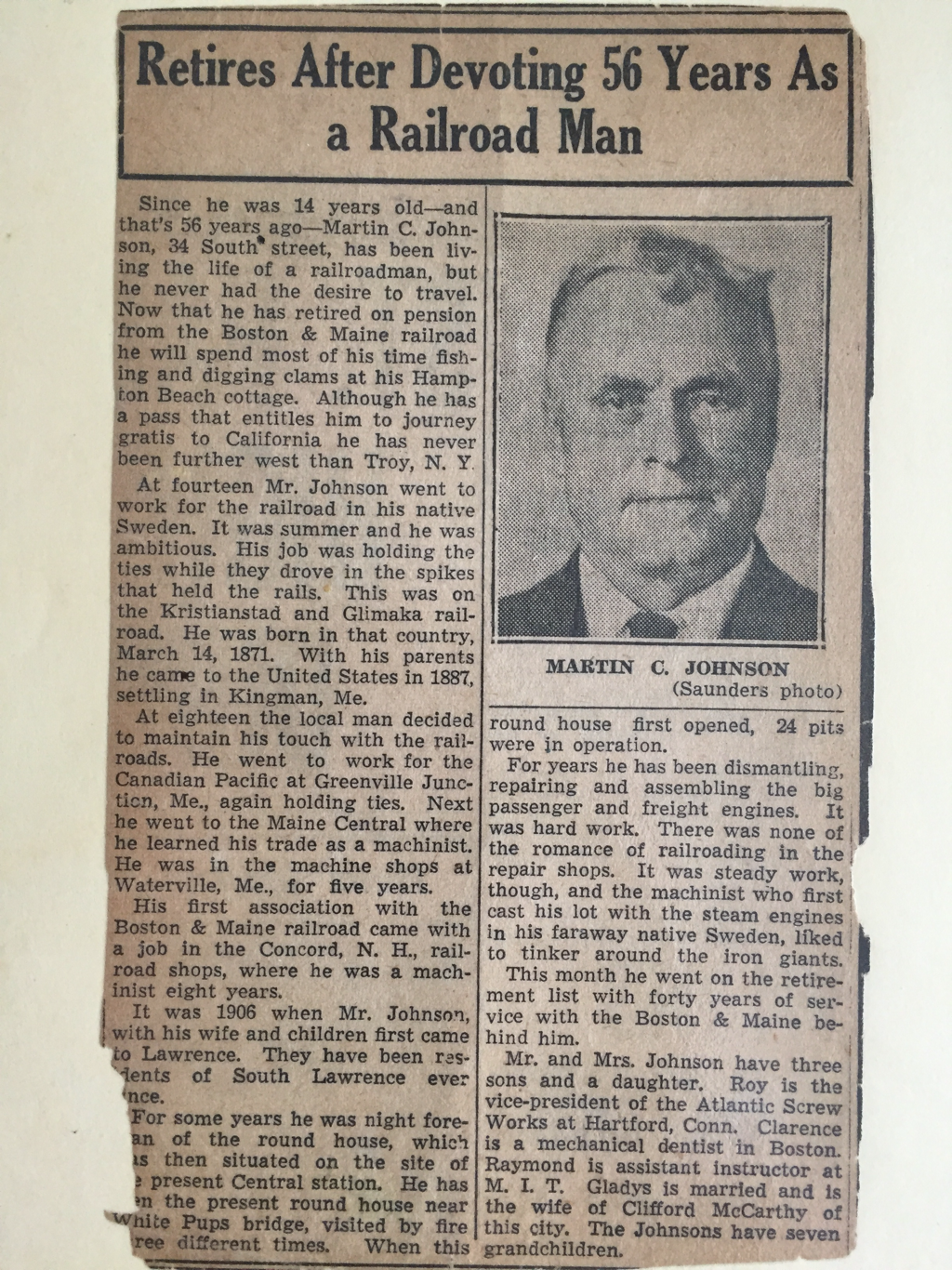

#52Ancestors challenge, week 7: My grandfather illustrates the industrial heritage of three towns2/18/2018 Below: My grandfather Clifford McCarthy, age 18, my grandmother Gladys Johnson, age 17, and my father, late autumn 1930(?). Recently, I asked my father to describe the work history of his father Clifford, who was born in Lawrence in 1912. Clifford married his high school sweetheart Gladys Johnson on his eighteenth birthday, February 3, 1930. She was four months pregnant with my father. They found a minister to do the wedding on the quick, in North Reading a few towns away. The stock market crash had been the previous October, before which Clifford's prospects seemed very different. Now, he was a married man with a family to support. Banks were failing and employers were closing. The Great Depression was descending over everything. He took his high school diploma that spring at Lawrence High and went to work. Below: The Kuhnardt Mill in Lawrence around 1930 judging by the cars in the background. This building still stands today. Source: Lawrence History Center .According to my father, "The first job of my dad’s, as I remember, from my pre-school days, was as a jig operator in the dye house at the Kuhnardt Mill by the Duck Bridge on the north side of the Merrimack River [in Lawrence]. His boss was his brother-in- law Wiliam Howarth. I heard complaints (from my mother?) that Bill picked on him." This was one of the stories of my grandfathers' employment history, working for in-laws who got him jobs. Later, he got a job with the Boston & Maine railroad through his father-in-law, who was an engineer. Years after that, in 1949, my father got a job working for his uncle Bill Howarth. It was at a dye house in Peterborough, New Hampshire. They were both working there because the mills in Lawrence were laying people off. Soon, the dye house in Peterborough also closed, and Bill Howarth moved to North Carolina to follow the textile industry south. But I digress... Because it was the Depression, there were times when my grandfather was laid off. "We received free flour from some source and my mother made "Johnny Cake” with it, which I liked," said my father. This is when New Deal programs allowed my grandfather to earn a wage. "He also worked with the WPA during the 30s. l distinctly remember a WPA arm band. I think he was involved with building side-walks, pick-and-shovel work." My father thinks he was part of the team of WPA workers that built Den Rock Park in Lawrence. Below: A bridge in Den Rock Park, Lawrence, Mass., that was likely built by WPA workers in the 1930s. The park sits at the intersection of Lawrence, Andover and North Andover My grandfather's next two factory jobs were in Andover, where by happenstance my father also was born a few years previous. "Thereafter as I remember it both parents worked a spell at the Shawsheen Mill (American Woolen Company). If this were so, my brother and I would have been living with my grandparents at 34 South. St. [Lawrence, on the Andover town line]." Below: The Shawsheen Mills in Andover in 1977, right before they were turned into apartments. Source: Andover Historical Society "I’m pretty sure the next job my father had, during World War 2, was at the Tyer Rubber Company, on Railroad St. (where Whole Foods is now). I think he was a warehouse man. As I remember he did bring home pairs of rubbers and overshoes at times. I was then in grammar school" The Tyer Rubber factory eventually was owned by Converse. Soles for their famous Chuck Taylor sneakers were apparently produced there, along with NHL hockey pucks. Manufacturing ceased there in 1977, and by 1990 the facility had been converted into apartments. As of late, there is even a Whole Foods in the front part of the facility, showing how far the town of Andover in particular has come from its quasi-industrial past! Below: My grandfather's eminently respectable parents on the occasion of their fiftieth wedding anniversary in North Andover, Mass., 1954 "The next job I believe dad had was with the B&M Railroad. I believe Grandpa Johnson, a mechanic with the B&M at the South Lawrence round house got him the job. The job was as a mechanic assistant at the round house in Boston. So this entailed a daily round trip by train. He worked there until he got laid off when the job of assistant mechanic was eliminated altogether, this was probably when Diesel engines replaced steam engines and assistant mechanics were no longer needed. I also remember him not showing on time for supper a number of nights. This occurred when he fell asleep on the train and woke up at the last stop in Haverhill. Then he would have to take the train back to Lawrence which probably got him back home about an hour after his due time." Below: My grandfather posing with other relatives in front of one of the Johnson family cottages at Hampton Beach, New Hampshire in the mid- to late- 1940s. He is lying down in front. His final job was in North Andover, at the huge Western Electric factory that was built there after World War II. "Next he worked at the Western Electric Plant in North Andover until retirement. I’m not certain what kind of work he did there, now it comes to me, I think he was a clerk in a tool crib, if you know what I mean. In any case he liked the work as I recall." "There is one more job he had," my father added. "This was as a janitor in the building [in Andover] where Phillips Academy’s school course books were sold. Now I don’t remember if he held this job before he went to work for Western Electric or after he retired. In any case I believe he worked his butt off there. It was the only time lever heard him complain about his work. He was not there for long, as I remember." Below: Osgood Landing, North Andover (largely vacant). Formerly the Western Electric Merrimack Valley Works, then an Alcatel plant. Eagle-Tribune photo. I've been told I can work like a dog, uncomplainingly. Maybe I got it from my grandfather. Even though my grandfather was a "working stiff" (as my father calls him), he regularly wore a jacket and tie when he wasn't at work. I don't know if this was a generational thing, or whether he did it consciously in an attempt to maintain some dignity despite his fairly plebeian economic status. He liked to sketch figures, including nudes copied from Playboy (an excuse to buy the magazines despite the certain protests of my fairly prim and proper grandmother). He exhibited a lot of [unmet] artistic talent that I also seem to have inherited, which is also basically unmet. Except I at least got the luxury of drawing real life nudes, when I was in the eleventh grade at Phillips Academy. Another general point: My grandfather's work history - spanning employers in Lawrence, Andover and North Andover - illustrates the free flow of people throughout an economically integrated area. One of the themes of my blog is the formerly integrated nature of "Greater Lawrence" (meaning Lawrence, Methuen, Andover, North Andover and Salem N.H.). The separate "ghetto" status of Lawrence is only a thing of the last thirty years. My father's family lived all over the Greater Lawrence area. It all seems like it was, back in the day, one big integrated area, even into the late 1970s and in my own early memory.

0 Comments

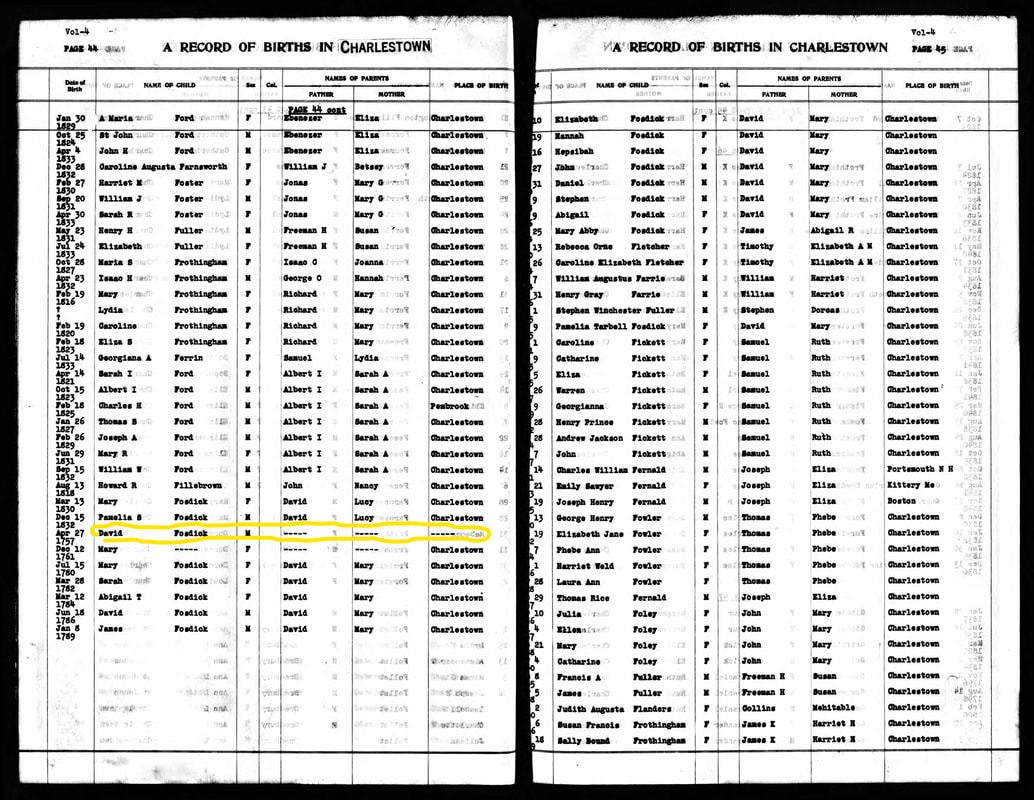

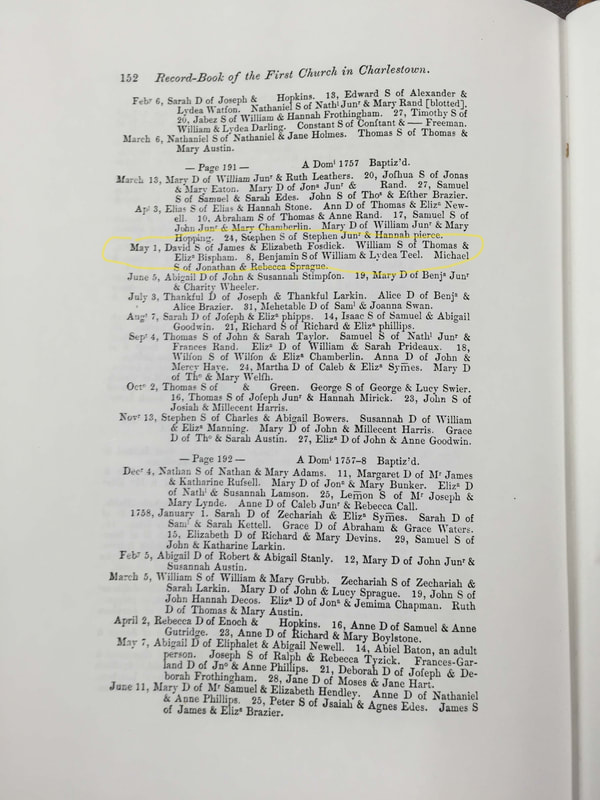

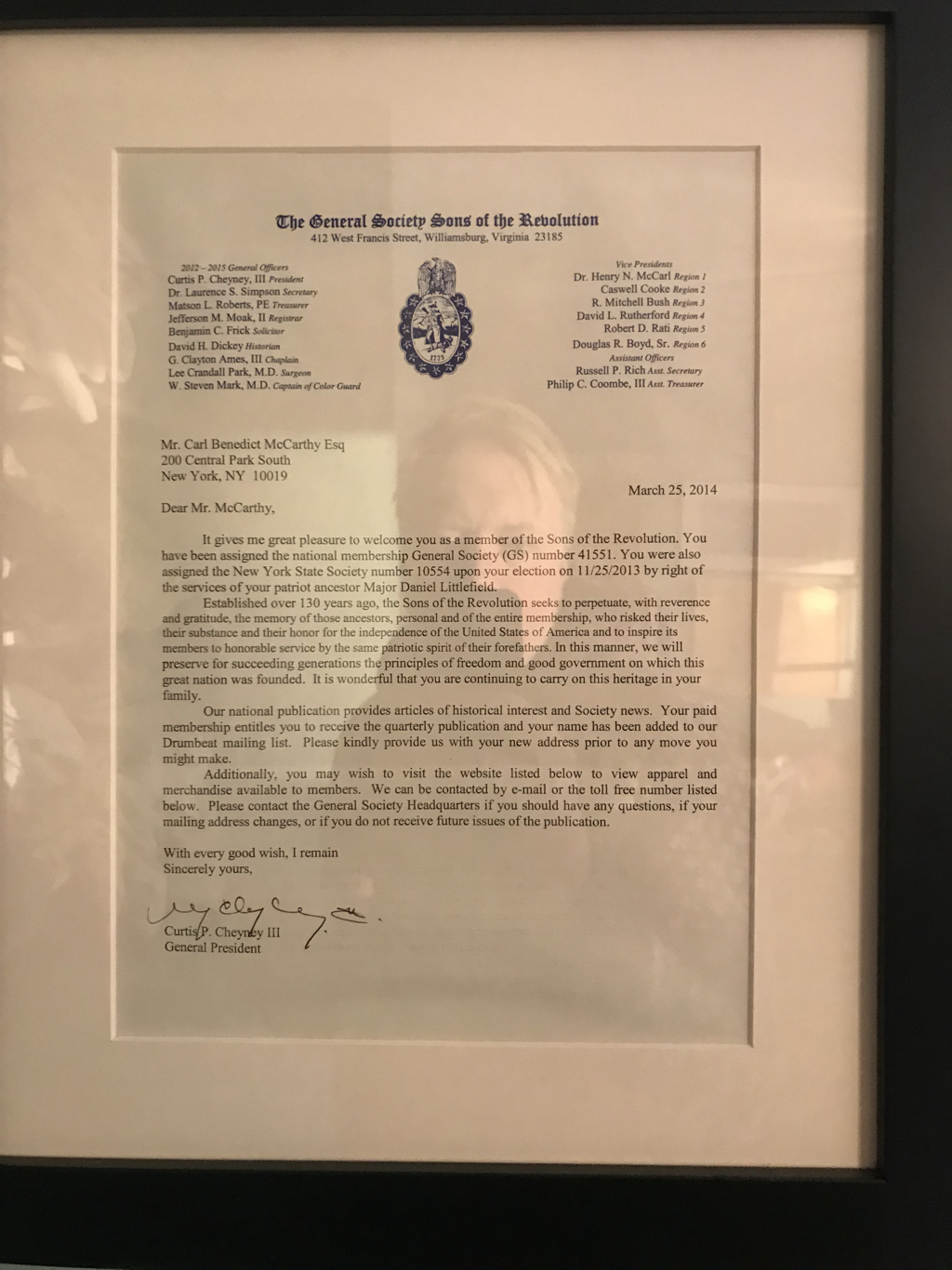

My genealogical line from William Brewster, spiritual leader of the Pilgrims, down to Edwin Ayer my great great grandfather, is as follows: Jonathan Brewster (1593 - 1659) son of William Brewster Ruth Brewster (1631 - 1677) daughter of Jonathan Brewster Mercy Pickett (1650 – d. New London, 1725) daughter of Ruth Brewster Samuel Fosdick (b. New London, 1684 – 1753 d. Charlestown)(buried Phipps cemetery) son of Mercy Pickett James Fosdick (b.1716 New London – d. 1784 Charlestown) (buried Phipps cemetery) son of Samuel Fosdick David Fosdick (b. 1757 Charlestown – d. 1812 Charlestown) (buried Phipps cemetery) son of James Fosdick Elizabeth Fosdick (b. 1791 Charlestown – d. 1855 Charlestown) daughter of David Fosdick Edwin Ayer (b. 1827 Charlestown – d. 1908 Lawrence). That's a lot of Fosdicks! What can I say about this clan (which, by the way, undermines my narrative that my ancestors arrived at the mouth of the Merrimack River and basically moved only 20 miles up river and then all stayed)? First point, the Fosdicks came to Charlestown, just north of Boston, and stayed there forever. So it's still North of Boston, meaning my basic claim holds up, that almost every American-born person from whom I'm descended was born North of Boston. I know of no ancestors born south of Boston except for the Fosdicks listed above, who moved to New London for just a few generations... probably to get away from insufferable puritans who ran Boston back then. They eventually moved back to Charlestown, however. So in my book, it's no harm, no foul! (Mr. Ayer above was of a Haverhill family; his father moved to Charlestown but he eventually moved back to Haverhill and married my great great grandmother Mary Jane Valpey of Andover, so I count him as being from the Merrimack Valley.) A couple of the Fosdicks in this list appear to have been n'er-do-wells. Stephen Fosdick (1583-1664), grandfather of Samuel Fosdick listed above, of Charlestown, Mass. was excommunicated from the puritan church for a period of twenty years, for crimes unspecified. How he got back into the good graces of the Elect is also not specified. His son John Fosdick (1626-1716) was charged with fornication by the Massachusetts authorities. “On 16 March 1649, John Fosdick, the constable of Charlestown was required (too was Ann the wife of Henry Branson) to appear at the next Court at Cambridge to answer for fornication committed by her with John Fosdick before she was married.” Despite this charge, he was allowed to remain constable, and served as a sergeant during King Philips War against the Indians in the 1670s. Another interesting thing is that, when I worked as a Park Ranger at Bunker Hill Monument in Charlestown, and lived in the Charlestown Navy Yard, I would walk to work past the Phipps Cemetery where all these Fosdicks are buried. Of course at the time, in 1994, I had no idea they were my ancestors! Anyway, my main challenge in proving lineage to William Brewster was that David Fosdick’s parent’s names were obliterated from the town birth records after the fact. Below: David Fosdick's entry in the birth records of Charlestown (circled in yellow). What happened that would cause the names of his parents (along with those of his wife's) to be obliterated from the town records?? One theory is that David Fosdick lost the family fortune - there were tales of a family "mansion" on the Charlestown neck, and hundreds of acres of land that were lost. How this happened, we don't know. Speculation in risky South Sea ventures? Ill-fated purchases of timberland in the wilds of northern Maine that got taken by the French? Investment in a merchant ship that didn't return from the Spice Islands? Anyway, I eventually surmounted this obstacle by obtaining the baptismal records for David Fosdick from the First (Congregational) Church of Charlestown. This involved my first physical research trip to conduct genealogical research, instead of just doing it online. At the magnificent facilities of the New England Historic Genealogical Society in Back Bay, I got my hands on a copy of these records. This was enough proof to satisfy the genealogist of the Mayflower Society that David Fosdick was indeed the son of James Fosdick listed above. Below: Baptismal records for David Fosdick, with a date corresponding to his birth date, and showing who his parents were. Thank god for my research that they weren't excommunicated at the time their son was born or this record would not exist. As a result of finding this evidence, my last document, the Mayflower Society genealogist accepted my application. A few months later, I received the certificate below.

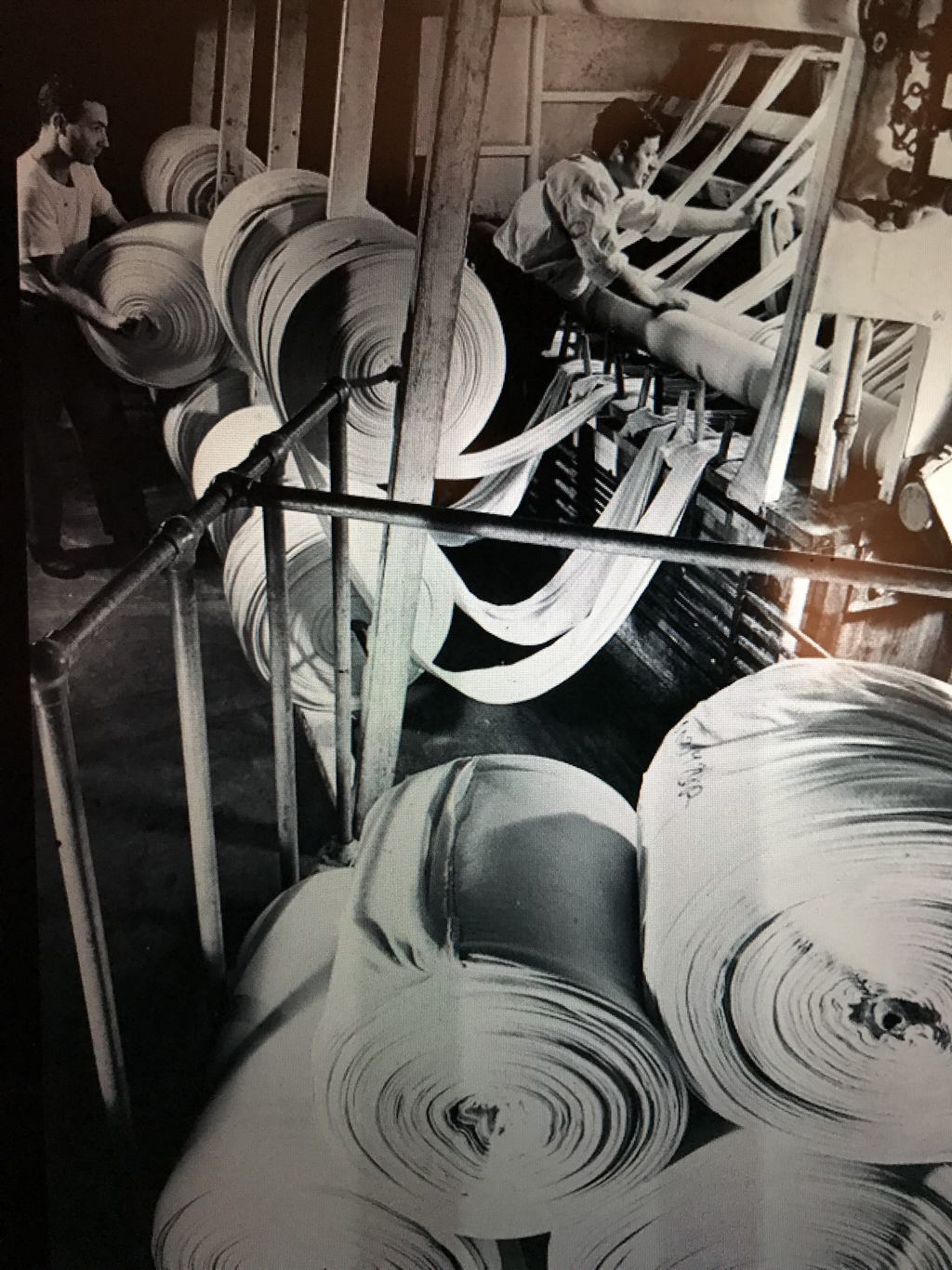

Above: men working in a dyehouse, 1940s Poem 38 Mill Work (a mock poem testimony) by Rich McCarthy, 2011 I was a Lawrence High School student in the 40s. The mills were humming: The Wood Mill, the Ayer Mill, the Arlington, the Pacific. Most every kid had a parent or relative working in a mill. My grandfather had been a weaver here Since he left Vermont at age nineteen (When his father died and the barn burned down.) [My note: the death of his father after a balloon accident is covered in another blog post.] In High School The worst the future could hold for us Was to end up in a mill after graduation We joked about becoming a mill rat. . . no way. My poor dad was a mill rat... in the dye house. And what did I do after I graduated. I took a job. Where? In a dye house. Like dad, I became a “jig” operator It wasn’t bad work; Except for the fumes: The hydrochloric acid, the ammonia, and the formaldrahyde fumes... Whew, sometimes it was overwhelming. I met some interesting people, Like the guy who never wore a shirt And had blue birds tattooed on his chest, One on each breast. Flying towards each other. I only lasted for two months. It wasn’t for me, a kid. I didn’t have to support a family. I left for a job with a magazine distributor. I was out of the mill. It was clean work: Putting up orders for drug stores. But the pay, 65 cents an hour, Stunk So what did I do? I went back to the mill. (The American Woolen Company) One buck an hour? I couldn’t believe it With benefits to boot! A Union shop, the CIO. So there I was, A back-boy Working the second shift, (two to ten), In the mule spinning room. The temperature was hot And humid. . . 90 degrees plus Humidifiers keeping it moist So the ends would not fall. The sweat poured over our brows We all wore head bands To keep it out of the eyes It was so hot we wore pants cut off at the knee, That’s all, no shirt, bare backed And old shoes with no socks It was a nice place to be in a winter storm, tropical. Cockroaches abounded. I stuck it out for about a year. The mills were shutting down, Moving south Where cheaper labor could be found, Or so we heard. So I got “laid off". .. permanently. Lawrence fell into hard times. The textile industry, as Lawrence knew it, Collapsed. But the experience taught me About organized labor, unions. I had got a decent wage. Because the job was so dirty, We were allowed a shower On company time at shift’s end. Because of the union, When we cleaned rollers, The machinery was disengaged. (Back-boys had been killed in prior years, Crushed to death when switches Were accidentally pulled.) Funny, as I think of it, I never heard of the strike of 1912 Not from my working stiff relatives, not in school. So I’m glad this is not the case today In Lawrence. And that we now celebrate The gutsy spontaneous reaction Of exploited immigrants Who made a better future for mill workers... All workers. And I might say, for me personally, A kid back in 1949. Below: The Wood Mill and the Ayer Mill at night, south bank of the Merrimack River, Lawrence, Mass., 1940s

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed