|

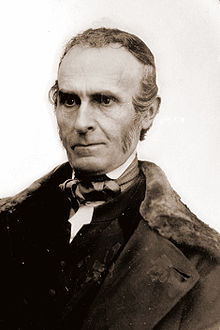

Below: John Greenleaf Whittier. Source: Wikipedia I'm supposed to do 52 profiles of ancestors in 2018 and I'm falling behind! So here is #8: John Greenleaf Whittier. He's a nearly forgotten poet who in his day was a household name. This was back before radio or TV, when people read (to themselves and to each other) for entertainment. John Greenleaf Whittier is not my ancestor. He can't be. He never had children. We are however, related...his great grandfather Joseph Whittier (1669-1717) of Haverhill is my eighth great grandfather. This makes us second cousins seven times removed. Say that ten times fast! Because he has been an important source for me in learning old stories of the area, I decided to include him in the 52 ancestors list. Below: John Greenleaf Whittier birthplace, Haverhill, Mass. (Source: Hampton N.H. Historical Society) Above: John Greenleaf Whittier Home and Museum, Amesbury, Mass., where he lived for over fifty years. Source: museum website So who was this guy, famous enough to have two historical museums in the area, one in Haverhill (where he was born) and one in Amesbury (where he lived when he was famous)? Basically, he was a self-educated farmer who lived in an ancient farmhouse in Haverhill - it was already well over a century old when he was born there in 1808 - that had been built by one of the founders of Haverhill. He wrote a lot of poetry, and was involved in the movement that wanted to abolish slavery in the United States. This activity got him into the circle of famous abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who was editor of a newspaper in Newburyport for a time. This newspaper started publishing Whittier's poems, and later when Garrison got more famous and began running in literary circles, he was able to promote Whittier. He became famous as a result of his poem Snowbound, about being snowed in. It starts like this: "The sun that brief December day Rose cheerless over hills of gray, And, darkly circled, gave at noon A sadder light than waning moon." Based on his literary fame for this and other poems, he eventually received an honorary degree from Harvard. Whittier himself barely left the area around Haverhill, other than a couple years in Philadelphia and New York when he was a young man. He complied lots of the historical stories of the Merrimack Valley area into poems. I have written blog posts about some of these topics, such as the story of Captain Waldron's deceit of the Indians and their revenge upon him; and the story of the Pennacook Indian princess Wenunchus, who drowned in the Merrimack as a result of a squabble between her father Passaconnaway and her husband Winnepurkett of Saugus. Back in Whittier's day, poems were sometimes epics, running thousands of lines. People would read them outloud to each other in the evening by lamplight or by the fire. I recorded myself reading The Bridal of Pennacook (in part), to get a feel for the language. That poem also provided a good geography lesson about upper reaches of the Merrimack River, which was the heartland of the Pennacook indians. The poem mentions Turee's brook, Contocook, "the Crystal Hills to the far southeast", Sunapee, Snooganock, Coos, Umbagog Lake, Ammonoosuc, Chepewass, "the Keenomps of the hills which throw/Their shade on the Smile of Manito"; Kearsarge, Babboosuck brook, Otternic, Sondagardee, Squamscot, Piscataquog...does anyone know these places??

2 Comments

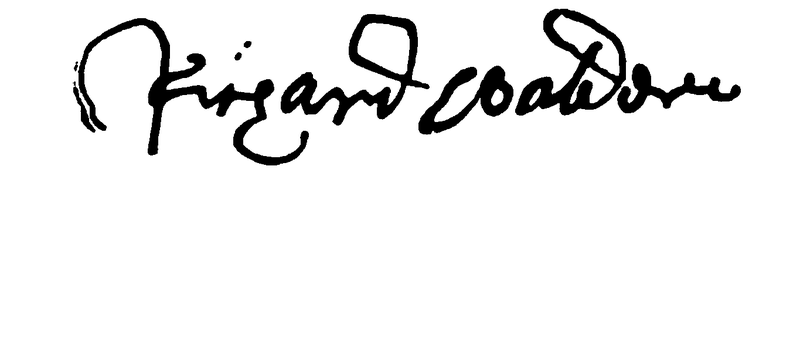

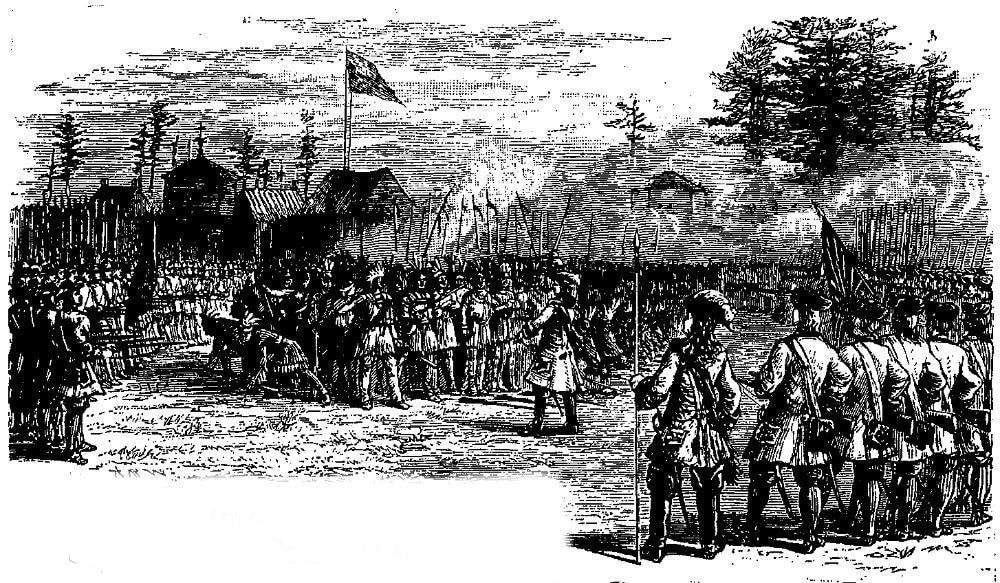

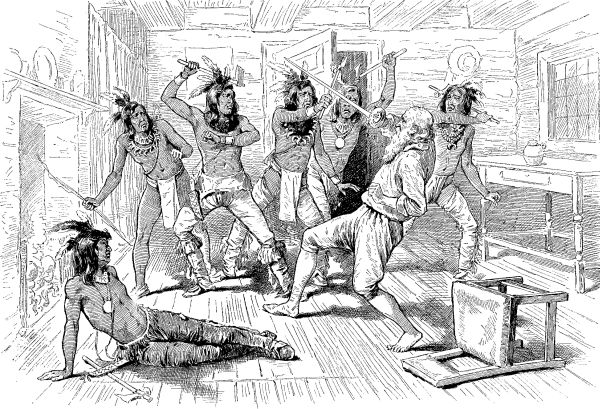

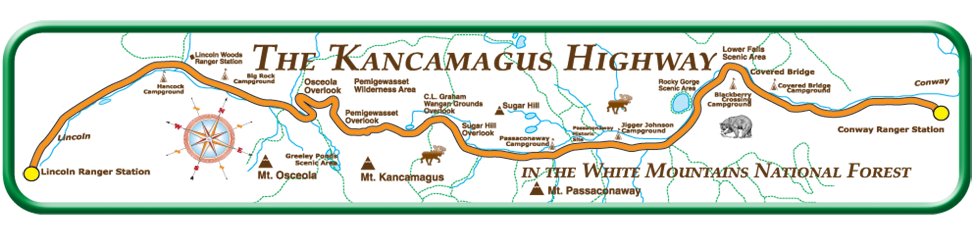

The Assassination of Major Richard Waldron by Kancamagus, last Sachem of the Pennacook Indians1/20/2018 Background The broad strokes of the story are already intriguing: First, we have an imperious colonial captain, Richard Waldron (or Walderne) who rules his frontier trading post at Cocheco (in modern-day Dover, New Hampshire) as his own personal fief. Although the towns of Hampton, Portsmouth, Exeter and Dover have temporarily come under Massachusetts jurisdiction (see Old Norfolk in the Glossary), this is an area where some settlers have claims to great tracts of land, Waldron being one of them. He gains notoriety for his treatment of Quaker missionaries to this area in 1662. He forces them to march eighty miles through the area in the dead of winter, having them publicly whipped every ten miles. Our chronologer of the area, John Greenleaf Whittier, covered it in one of his poems: Bared to the waist, for the north wind's grip And keener sting of the constable's whip, The blood that followed each hissing blow Froze as it sprinkled the winter snow. Waldron is also known for sharp practices ripping off his native American trading partners. For example, when they catch him putting his hand on the scales, he tells them his fist weights exactly a pound so they are not being deceived. The Indians nevertheless return to his post because of its proximity and convenience, and his supply of useful wares. Then we have Kancamagus, grandson of Passaconnway, great sachem of the Pennacooks. In 1684, he appears on the scene, writing a letter to the governor, in which he calls himself John Hogkins, asking for protection against the Mohawks, ancient enemies of the New England indians. Whether the governor provided protection is not known. In any case, Kancamagus a.k.a. John Hogkins forswears the peaceable ways of Wonalancet, his uncle. In 1689, he vows to stand up to the English. Because there are barely any Pennacooks left to lead, he leads an alliance with the natives of the Androscoggin River valley. Waldron in King Philip's War In the native uprising of 1675 known as King Philip's War, Major Waldron signed a peace treaty with the local sachem, the hapless Wonalencet. Below: The signature of Richard Walderne a.k.a. Waldron As a gesture of peace after the treaty, in September 1676, Waldron invites his Pennacook trading partners into a playing a "game" with the company of men he commands. However, it's actually a trap. He proposes a mock "battle", in which the Indians are given a canon to use, with powder but no shot. While they are awed and distracted by this device, the 400 natives are surrounded by four companies of colonial men, and disarmed. The Indians are then sorted, with the individuals known to be peaceable -- such as Christian converts living in the Praying Towns along the Merrimack -- allowed to go free. The remaining two hundred Indians are imprisoned and sent to Boston for trial. Seven are hanged for treason and the remainder are sold into slavery in Barbados. Some accounts say Wonalencet himself was transported to Barbados, but managed to make his way back home. In any case, the authority of Wonalancet was shattered, and eventually his nephew Kancamagus took up the mantle of "sachem" of the Pennacooks. Below: A nineteenth century illustration of the "Deceit of Captain Waldron" wherein the Indians are surrounded and captured. According to a 1989 commemoration of the 300th Anniversary of the "Cocheco Massacre", the event took place in a field where the parking lot for Aubuchon Hardware currently is. Waldron in King William's War: The "Crossing Out of the Account" Fast-forward thirteen years. There is a new war between the English and the natives, known as King William's War. (See the Glossary.) Captain Richard Waldron is now Major Richard Waldron. He is an old man of means and status. For example, he had been the second president of the Royal Council of New Hampshire, a governing body created by the separation of Old Norfolk from Massachusetts. His trading post, on the Cocheco River, is comprised of five garrison houses. He is warned that a large band of natives have assembled at Pennacook (modern-day Concord, New Hampshire), with the intent of attacking him. They are led by Kancamagus, who vows to avenge the false hospitality and deception that led to the destruction of his tribe. Below: A surviving garrison house from the 1670s, photographed in the mid-nineteenth century When warned about the threat, Major Waldron is dismissive. He is supposed to have said "let them go plant their pumpkins" --- which I guess means "go about your business and don't worry about it". On the night of June 27, 1689, according to the Indians' plan of attack, two squaws requested permission to lodge in each garrison at Cocheco. This was apparently a common practice, to grant lodging to local Indians known to the colonists. "No fear was discovered among the English, and the squaws were admitted. One of those admitted into Waldron's garrison, reflecting, perhaps, on the ingratitude she was about to be guilty of, thought to warn the Major of his danger. She pretended to be ill, and as she lay on the floor would turn herself from side to side, as though to ease herself of pain that she pretended to have. While in this exercise she began to sing and repeat the following verse: O Major Waldon, You great Sagamore, O what will you do, Indians at your door! No alarm was taken at this, and the doors were opened [by the native women] according to their plan, and the enemy rushed in with great fury. They found the Major's room as he leaped out of bed, but with his sword he drove them through two or three rooms, and as he turned to get some other arms, he fell stunned by a blow with the hatchet. They led him into his hall and seated him on a table in a great chair, and then began to cut his flesh in a shocking manner. Some in turns gashed his naked breast, saying, "I cross out my account." [meaning, our account is now settled.] Then, cutting a joint from a finger, would say, " Will your fist weigh a pound now'!'' His nose and ears were then cut off and forced into his mouth. He soon fainted, and fell from his seat, and one held his own sword under him, which passed through his body, and he expired. The family were forced to provide them a supper while they were murdering the Major.” (From: The History of the Great Indian War of 1675 and 1676, Commonly Called King Philips War by Thomas Church (Hartford, 1851)(ed. Samuel G. Drake)). Below: A nineteenth century depiction of the assassination of Major Waldron. Kancamagus disappeared into the wilderness of the Androscoggin valley, along with twenty-nine captives to be held for ransom. Vengeance had been served. And so ends the tale of Major Waldron. Or does it? Interpreting and Analyzing the Story The "crossing out of the account" is a compelling narrative of deceit and retaliation. If you go further into the details, though, it is also important for illustrating how personal these battles (to the death) between English and Indians were. Generally speaking, the attackers were not anonymous natives from afar. Everyone was known to everyone. And whole families were involved, with both sides capturing the others' wives and children to use as bargaining chips. This led to cycles of violence and retribution. For example, Captain Charles Frost of Kittery, who commanded one of the four companies that captured the indians in Waldron's deceit in 1676, was hunted down and assassinated in Eliot, Maine on July 4, 1697. Frost himself had been inspired to treat the natives with hostility by an attack on his family in 1650, in which his mother and sister were killed. Perhaps the most famous case of a cycle of personal vengeance was Jeremy Moulton's. At the age of four, his parents were killed and he was captured in the devastating 1692 raid on York, Maine, probably the most destructive Indian raid in New England. Fast forward to 1724, and he was leading the successful attack on Father Sebastian Rale, the French Jesuit missionary who instigated the attacks, killing him and many Indians at present-day Norridgewock, Maine. In other cases, the connection was one of mutual mercy instead of mutual retribution. According to Cotton Mather’s Magnalia Christi Americana [a.k.a. Ecclesiastical History of New England], Elizabeth Heard was a witness to Waldron’s deceit in 1676, and there she sheltered a young native Abenaki boy from death. On the night of the Cocheco Massacre, an Indian pointed his musket at her, but suddenly spared her life because of the recognition of who she was. Her house, defended by William Wentworth because her husband had recently died, was not invaded. Among the twenty nine captives taken during the Cocheco Massacre were Sarah Gerrish, the 7 year old granddaughter of Major Waldron, and Esther Lee, daughter of Richard Waldron along with her (presumably infant) child. Lee's husband was killed in the raid, and her infant child did not survive captivity. She and the little girl Gerrish her niece were both ultimately returned to Dover in a prisoner exchange. The use of family members as captives ultimately led to the downfall of Kancamagus. In September 1690, an English force under the command of Capt. Benjamin Church located and attacked Kancamagus’s village on the Androscoggin River. Somehow, Kancamagus was able to escape the attack, but his family wasn’t so lucky. His sister was slain and his brother-in-law, wife and children were taken captive, although his brother-in-law was later able to escape. Captain Church took the captives to Wells, Maine, where they were used to try to lure Kancamagus to the peace table. In response to the attack on his village and the capture of his family, Kancamagus launched an attack on Church at Casco, Maine, on Sept. 21. After a great deal of hard fighting, which resulted in the death of seven of Church’s men and 24 wounded, Kancamagus was beaten back. With the English still holding his family hostage, Kancamagus was forced to make peace with the English at Wells. Following this agreement of peace, Kanacamagus was reunited with his family. After 1692, little is written about Kancamagus. It’s possible that once he recovered his family, he continued to fight alongside other Abenaki people, although that is purely speculation. His name lives on in the scenic road well-loved by leaf peepers. However, I'm sure that, as tourists drive the Kancamagus Highway, they have scant knowledge of the story of his life. Above: map of the Kancamagus Highway. Source: http://kancamagushighway.info/Native American History and Poetic License (a long read) Once upon a time, so the story goes, about 1628 – right when the English puritans were beginning to arrive to claim their promised land around Massachusetts Bay – there was a wedding of a native princess. She was the daughter of Passaconaway, the great Bashaba of the Pennacooks. The Pennacooks were the natives of the Merrimack Valley. Their domains extended from present day Haverhill all the way up to its headwaters along the Pemigewasset. The Bashaba made his home at a curve in the river, called Pennacook, site of present day Concord N.H. The tribe and affiliated bands of natives – Wachusetts, Agawams, Wamesits, Pequawkets, Pawtuckets, Nashuas, Namaoskeags, Coosaukes, Winnepesaukes, Piscataquas, Winnecowetts, Amariscoggins, Newichewannocks, Sacos, Squamscotts, and Saugusaukes – also met at prescribed times at various sites along the river, usually to fish: for example, at the falls at Amoskeag, later the source of waterpower for the mills at Manchester, N.H.; Pawtucket, later the source of waterpower for the mills at Lowell; and at Pentucket, later called Haverhill. According to a 1981 book on the Forgotten Salmon of the Merrimack, there were fourteen sets of falls on the mainstream of the Merrimack River, including on the Pemigewasset, where natives could have fished for salmon. The natives also met each year at the Weirs, fish traps designed to catch a bountiful harvest flowing out of swollen Lake Winnipesauke. This is where she met her groom, known as Ahquedaukenash (meaning "dams" or "stopping-places"). In the present day it’s called Weirs Beach. The groom was Montowampate, son of the “Squaw Satchem”, the female leader of the coastal Saugus Indians who took over when her husband Nanepashemet was killed battling their rivals, the Tarrantines, on August 8, 1619 in present day Ipswich, Massachusetts. How do we know any of this? From written records of English settlers mainly, and retellings of the story. The English settlers tell the stories of the Indians Passaconnaway and Sagamore James, as he was known to the English, were undoubtedly historical figures who signed deeds and, in the case of the latter, sought redress from English authorities to protect his interests and who is described as wearing English clothes. “Sagamore James went to Governor Winthrop on March 26, 1631, in order to recover twenty beaver skins of which he had been defrauded by an Englishman named Watts.” I hope to write more on the historical record left by natives in English colonial society, particularly the descendants of Nanepashemet who regularly tried to use the English courts to protect their land rights, in another blog entry. The first telling of the wedding story of this (yet unnamed) princess, daughter of Passaconaway, was by Thomas Morton, founder of the ill-fated Merrymount Colony. “The Sachem or Sagamore of Saugus made choice, when he came to man's estate, of a lady of noble descent, daughter to Papasiquineo [another name for Passaconnaway], the Sachem or Sagamore of the territories near Merrimack river, a man of the best note and estimation in all those parts, and (as my countryman Mr. Wood declares in his prospect) a great Necromancer; this lady the young Sachem with the consent and good liking of her father marries, and takes for his wife. Great entertainment he and his received in those parts at her father's hands, where they were feasted in the best manner that might be expected, according to the customs of their nation, with reveling and such other solemnities as is usual amongst them. The solemnity being ended, Papasiquineo causes a selected number of his men to wait upon his daughter home into those parts that did properly belong to her Lord and husband; where the attendants had entertainment by the Sachem of Saugus and his countrymen: the solemnity being ended, the attendants were gratified. Not long after the new married lady had a great desire to see her father and her native country, from whence she came; her Lord willing to please her, and not deny her request, amongst them thought to be reasonable, commanded a selected number of his own men to conduct his lady to her father, where, with great respect, they brought her, and, having feasted there a while, returned to their own country again, leaving the lady to continue there at her own pleasure, amongst her friends and old acquaintance, where she passed away the time for a while, and in the end desired to return to her Lord again. Her father, the old Papasiquineo, having notice of her intent, sent some of his men on embassy to the young Sachem, his son-in-law, to let him understand that his daughter was not willing to absent herself from his company any longer, and therefore, as the messengers had in charge, desired the young Lord to send a convoy for her, but he, standing, upon terms of honor, and the maintaining of his reputation, returned to his father-in-law this answer, that, when she departed from him, he caused his men to wait upon her to her father's territories, as it did become him; but, now she had an intent to return, it did become her father to send her back with a convoy of his own people, and that it stood not with his reputation to make himself or his men too servile, to fetch her again. The old Sachem, Papasiquineo, having this message returned, was enraged to think that his young son-in-law did not esteem him at a higher rate than to capitulate with him about the matter, and returned him this sharp reply; that his daughter's blood and birth deserved more respect than to be so slighted, and, therefore, if he would have her company, he were best to send or come for her. The young Sachem, not willing to undervalue himself and being a man of a stout spirit, did not stick to say that he should either send her by his own convey, or keep her; for he was determined not to stoop so low. So much these two Sachems stood upon terms of reputation with each other, the one would not send her, and the other would not send for her, lest it should be any diminishing of honor on his part that should seem to comply, that the lady (when I came out of the country) remained still with her father; which is a thing worth the noting, that savage people should seek to maintain their reputation so much as they do.” So when Thomas Morton “came out of the country” in 1629 (a euphemism for “getting expelled by puritans”), the bride apparently was still stuck up the Merrimack away from her groom, because nobody would escort her back down to Saugus. Later tellings of the story give her a definitive identity, Wenunchus. Alonzo Lewis, in his 1829 history of the town of Lynn (including Lynnfield, Saugus, Swampscott and Nahant, all of which were set off from Lynn), gives her this name… and also completes the story, sort of: “My lady readers will undoubtedly be anxious to know if the separation was final. I am happy to inform them that it was not; as we find the Princess of Penacook enjoying the luxuries of the shores and the sea breezes at Lynn, the next summer. How they met without compromising the dignity of the proud sagamore, history does not inform us; but probably, as ladies are fertile in expedients, she met him half way. In 1631 she was taken prisoner by the Taratines, as will hereafter be related. Montowampate died in 1633. Wenuchus returned to her father; and in 1686, we find mention made of her grand-daughter Pahpocksit.” Parts of the historical record of the English are very clear. According to the diary of John Winthrop, Montowampate and “almost all of his people” died of smallpox in September 1633. Below: Montowampate on the seal of the Town of Saugus, Massachusetts However, other historians have Wenunchus married to the younger brother of Montowampate, named Wenepoykin, a.k.a. Winnepurkett, called Sagamore George, who lived for many years, dying in 1684. Yet, even though he outlived his brother by half a century, his life was probably even more tragic. He was sold by the Puritans into slavery in Barbados in 1676 after being deemed a belligerent in King Phillips War...only to miraculously return like some lost prophet. After his return, he retired to Wamesit, the Praying Town for settled Indians, where he lived out his days, dying in 1684. As the recognized leader of the Saugus Indians and thus owner of the land from Salem to Saugus, immediately after his death the townspeople of Marblehead descended upon his “heirs”, including his elderly wife (not Wenunchus), obtaining a deed for their town on September 14, 1684. The deed was signed by Ahawayet, and many others, her relatives. She is called "Joane Ahawayet, Squawe, relict, widow of George Saggamore, alias Wenepawweekin." (Essex Reg. Deeds, 11, 132.) I suppose you can still go down to the land records office in Salem and look at her signature! The townspeople of Lynn and Salem soon followed suit, obtaining deeds from the heirs of Wenepoykin on September 4, 1686 an October 11, 1686 respectively. (Source: History of Essex County Massachusetts, 1888, by Duane Hamilton Hurd) But what if Wenunchus married Wenepoykin, not Montowampate, but also didn’t survive the shuttling between husband and father? This is the narrative tack taken, with some apparent poetic license, by one of the most famous poets of the mid-nineteenth century, and certainly the most famous poet until Robert Frost to be claimed by the lower Merrimack Valley region. (Robert Frost being claimed, rather surprisingly, by Lawrence because he graduated from Lawrence High School.) I am talking about John Greenleaf Whittier. The Story of Wenunchus in the Hands of John Greenleaf Whittier John Greenleaf Whitter was born on an ancient farm in Haverhill in 1807. It was built by his first Whittier ancestor in Haverhill almost a 150 years earlier. Although Whittier was self-educated, by the time he died in 1892, he was the author of one of the most famous poems of the day, Snowbound. This long piece, published in 1866, describes being stuck in the farmhouse on a snowy day, and it made him well-off financially. He ran in literary circles, mainly on account of being mentored in his younger days by an earlier publisher of his works, William Lloyd Garrison, in Garrison’s Newburyport newspaper. Garrison introduced him to the abolitionist cause, and to many literary lights of his day. Through these connections and the recognition he received for Snowbound, the self-educated Whittier received an honorary degree from Harvard in 1877. For his entire life, except for a spell of about three years working in New York and Philadelphia, he barely left the Haverhill-Amesbury-Newbury area. When Whittier did finally manage to see a bit of the world, it was mainly just places like the White Mountains and the Isles of Shoals. Whittier’s extreme provincialness, despite his involvement in the abolitionist movement and his honorary Harvard degree, is to me what gives his poems their authenticity. He is, to me, the voice of the historic lower Merrimack Valley. Snowbound is not just about being stuck indoors on a snowy day, it is about Haverhill and its history and setting. And one of his earlier epic tales, the Bridal of Pennacook, which tells the tale of Wenunchus and her marriage to [in Whittier’s version] Wenepoykin, whom he calls Winnepurkit, the poem is a vehicle for glorifying the entire Merrimack River, from the coastal sand dunes right up to the river’s highest headwaters. About his poem, “The Bridal of Pennacook” The poem was apparently written in 1844 but not included in any book of poetry for many decades. It is long – twenty five pages. It employs a conceit that the poem is composed spontaneously for entertainment by five hikers staying in a lodge near Mount Washington while the youngest of them recovers from her cold. The five characters who together compose the poem for their entertainment are the narrator, a writer and a poet; a city lawyer, “Briefless as yet, but with an eye to see /Life's sunniest side, and with a heart to take/Its chances all as godsends”; his brother a student training to be a minister, “as yet undimmed/By dust of theologic strife, or breath/Of sect”; a shrewd sagacious merchant, “To whom the soiled sheet found in Crawford's inn, /Giving the latest news of city stocks/And sales of cotton, had a deeper meaning/Than the great presence of the awful mountains/Glorified by the sunset”; and the merchant’s lovely young daughter, “A delicate flower on whom had blown too long/Those evil winds, which, sweeping from the ice/And winnowing the fogs of Labrador.” Whittier thus sets the scene: So, in that quiet inn Which looks from Conway on the mountains piled Heavily against the horizon of the north, Like summer thunder-clouds, we made our home And while the mist hung over dripping hills, And the cold wind-driven rain-drops all day long Beat their sad music upon roof and pane, We strove to cheer our gentle invalid After the lawyer tells her stories of his (mis)adventures fishing in the Saco River, and the divinity student, “forsaking his sermons”, recites poems to her from memory, the narrator rummages through the musty book collection at the inn, where he finds “an old chronicle of border wars and Indian history.” From this book the narrator reads aloud a summary of the story of Wenunchus and Montowampate, except in this version she is called Weetamoo (actually the name of a wife of a prominent native chief in Rhode Island) and, instead of marrying Montowampate, she marries that man’s brother Wenepoykin, whom he calls Winnepurkit. Our fair one [i.e. the girl], in the playful exercise Of her prerogative,—the right divine Of youth and beauty,—bade us versify The legend, and with ready pencil sketched Its plan and outlines… The self-taught Whittier tries to show his knowledge of classical Greek poetical forms, which I suppose was de rigeur for professional poets of the era. He does not say which character “versifies” which part of the Wenunchus story, but it might be possible to hazard a guess based on their supposed personalities. In the first section, the poem sets the scene, describing the pre-contact Merrimack River itself, “ere [before] the sound of an axe in the forest had rung, Or the mower his scythe in the meadows had swung.” This section is in so-called Alexandrine meter, twelve syllables per line with a stress on the sixth and last, in simple A-A B-B rhyme. Among other things, it takes the listener through the geographic features of the river: “Amoskeag's fall”, the “twin Uncanoonucs” stately and tall, the Nashua meadows green and unshorn, etc., all before “the dull jar of the loom and the wheel,/The gliding of shuttles, the ringing of steel” had invaded the river in the form of mills and waterworks. In the next section, the poem describes the stern character of The Bashaba, i.e. the great chief Passaconaway, in a more complex format: paired quatrains, rhyming aaab cccb, with 7-7-7-5 syllables, while the first stanzas are longer, nine lines for the first, ababbaddd. The character telling this section – the lawyer, perhaps? – weaves a tale of the awe inspired by Passaconaway: Here the mighty Bashaba Held his long-unquestioned sway, From the White Hills, far away, To the great sea's sounding shore; Chief of chiefs, his regal word All the river Sachems heard, At his call the war-dance stirred, Or was still once more. In the third section, the poem describes The Daughter, Weetamoo. The description focuses on her mother’s death giving birth to her (a detail certainly conjured up with poetic license), and the joy she ultimately brings to her stern old father, who decides not to take another wife. The meter and rhyme for this section is rather simple, likely the work of the merchant character; for the rest of this blog piece I’ll refrain from detailing the rhyming scheme of each section. The fourth section describes The Wedding itself: The trapper that night on Turee's brook, And the weary fisher on Contoocook, Saw over the marshes, and through the pine, And down on the river, the dance-lights shine. For the Saugus Sachem had come to woo The Bashaba's daughter Weetamoo, The fifth section describes Weetamoo’s New Home with her new husband, in the coastal marshes of Saugus far from her mountain homeland. Whoever tells this part of the tale is rather uncharitable about the coastal terrain of Essex County: A wild and broken landscape, spiked with firs, Roughening the bleak horizon's northern edge; And later, an equally dreary scene, it is contrasted with the mountain home of Weetamoo: And eastward cold, wide marshes stretched away, Dull, dreary flats without a bush or tree, O'er-crossed by icy creeks, where twice a day Gurgled the waters of the moon-struck sea; And faint with distance came the stifled roar, The melancholy lapse of waves on that low shore. No cheerful village with its mingling smokes, No laugh of children wrestling in the snow, No camp-fire blazing through the hillside oaks, No fishers kneeling on the ice below; Yet midst all desolate things of sound and view, Through the long winter moons smiled dark-eyed Weetamoo. There is an oblique reference to Weetamoo's sexual awakening as a wife ("o'er some granite wall/Soft vine-leaves open to the moistening dew"). However section ends with her husband sending her back home to assuage her homesickness, escorted by soldiers: Young children peering through the wigwam doors, Saw with delight, surrounded by her train Of painted Saugus braves, their Weetamoo again. The sixth section describes her time back at Pennacook, at first enjoyable but then fraught with anxiety when her husband does not summon her back: The long, bright days of summer swiftly passed, The dry leaves whirled in autumn's rising blast, And evening cloud and whitening sunrise rime Told of the coming of the winter-time. But vainly looked, the while, young Weetamoo, Down the dark river for her chief's canoe; No dusky messenger from Saugus brought The grateful tidings which the young wife sought. The clash of egos between her father and her husband overtakes the situation and she is forced to spend the winter up in Pennacook. The section ends with her fixing to leave as soon as the river thaws, by herself, down the Merrimack. The seventh section, the Departure, describes her planning then and her actual flight. The river is swollen with rain and snowmelt, full of iceflows. At first, she appears to be managing despite the danger: Down the vexed centre of that rushing tide, The thick huge ice-blocks threatening either side, The foam-white rocks of Amoskeag in view, With arrowy swiftness sped that light canoe. However, things start to go wrong: The small hand clenching on the useless oar, The bead-wrought blanket trailing o'er the water… It ends dramatically: Sick and aweary of her lonely life, Heedless of peril, the still faithful wife Had left her mother's grave, her father's door, To seek the wigwam of her chief once more. Down the white rapids like a sear leaf whirled, On the sharp rocks and piled-up ices hurled, Empty and broken, circled the canoe In the vexed pool below—but where was Weetamoo? The final section of the poem, the Song of Indian Women, is a coda of sorts, sang by “the Children of the Leaves beside the broad, dark river's coldly flowing tide.” The Dark eye has left us, The Spring-bird has flown; On the pathway of spirits She wanders alone. The song of the wood-dove has died on our shore Mat wonck kunna-monee! We hear it no more! You can read all of The Bridal of Pennacook by John Greenleaf Whittier online. The poem should be read out loud for its full impact. I tried to do just that. You can watch my efforts reading the entire poem (which takes about an hour) at these videos below. Someday I’d like to replace the awkward video images of my contorted mug reading, with a slide show of the New Hampshire landscape to accompany the poetry. Poetic license and appropriation of “other people’s stories” John Greenleaf Whittier applied poetic license to the story handed down by Morton and others. He embellished it and added details for dramatic effect. Should he be telling the story of Wenunchus at all? Current cultural sensitivities caution against “cultural appropriation.” Because Whittier was not a Pennacook Indian, should he be writing poetry about Pennecooks? How about the fact that he sets up the poem around discovery of “an old chronicle of border wars and Indian history”? Does this make the poem about something likely to be found in old New England of the 1840s, when the memory of French and Indian wars was fresher, and the sight of actual Native Americans along the Merrimack could still be something of living memory? And what if there are no Pennacooks left to tell the story? Can someone else tell the story? Should only native Americans tell the story? Some natives were enemies of the Pennacooks. For example, the Mohawks were fierce warriors who would raid Pennacook lands periodically from beyond the Hudson River and steal their grain stores. A huge battle between Mohawks and Pennacooks apparently occurred in 1615, when the Mohawks attacked Pennacook itself. Other tribes with which the Pennacooks sometimes battled included the Abenaki and the Taratines. I would argue that the inheritors of these tribes, some of which still exist, have no direct claim to the stories of the Pennacooks. Do the current inhabitants of the Merrimack Valley region have a right to appropriate the stories of the Pennacooks? It is probably true that the settlement by the English starting in 1620, and the diseases they brought, followed by war and appropriation of land, led to the extinction of the Pennacooks. Does that mean the descendants of actors in the 1600 and 1700s are barred from telling these stories? How about the fact that many “tribes” arrived in the Merrimack Valley only after the Pennacooks were long-extinct: the Irish, the Italians, the French-Canadians, the Dominicans, the Puerto Ricans…do they have less or more of a right to tell these stories about the history of their present-day land? My own belief is that artists can interpret any story, and whether it is offensive or not depends on specific presentation. It is never categorical based on some construct of the artists “tribe” versus that of his subject matter. The poetry of John Greenleaf Whittier is largely forgotten, even among people who read poetry. A lot of it is sentimental and cliched, and comes across as long-winded and maudlin to me. But within his oeuvre, there are nuggets everywhere about the Merrimack Valley and his home. People can get reacquainted with the old stories of their home, simply by reading his works. The Bridal of Pennacook is one story that is worth retelling. Maybe someday it will be turned into a musical? John Eliot, pastor at Roxbury in puritan Massachusetts Bay Colony, developed an interest in saving native souls, apparently on account of his language skills. So in 1649 he petitioned Parliament back in England for support in the conversion of the Indians of New England. Parliament duly funded the Corporation for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England, with Eliot as its head.

The chief results of this enterprise were (1) production of an Algonquin language bible, which also required teaching hundreds of natives how to read; and (2) the formation of so-called Praying Towns, where Christianized Indians were supposed to settle. By 1674, on the eve of King Philips War, the first major conflict between natives and English colonists, the population of Eliot's praying towns numbered 4,000 Indians, according to Major Daniel Gookin, the first and only commissioner of Indian matters in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Native responses to Christianity varied widely. Some were hostile. For example, when Metacom, also known as Philip, the leader of the rebellion called King Philip's War, was preached to by Reverend Eliot, Metacom was disrespectful. He supposedly took hold of a button on Eliot's coat and said "I care no more for your religion than I do for this button" and yanked it off. Other natives stayed ambivalent, while yet other Indians instead were persuaded by Catholic missionaries coming down from New France of the superiority of Catholicism. Passaconnaway, the great chief of the Pennacooks, politely listened to Eliot's preaching as far up the Merrimack River as Amoskeag, present day Manchester, New Hampshire. His son Wonalancet, however, dutifully accepted Christianity fully. In May 1674, Wonalancet informed Reverend Eliot and his cohort of ministers: "Sirs, you have been pleased, for years past, in your abundant love, to apply yourselves particularly unto me and my people, to exhort, press, and persuade us to pray to God; I am very thankful to you for your pains. I must acknowledge I have all my days been used to pass in an old canoe, and now you exhort me to leave and change my old canoe and embark in a new one, to which I have been unwilling; but now I yield myself to your advice and enter into a new canoe and do engage to pray to God hereafter." At this time, Wonalancet and his followers apparently settled in Wamesit, present day Tewksbury although then called East Chemsford, which comprised 2,500 acres along the Merrimack River near its confluence with the Concord River. They picked a bad time to "enter a new canoe", however, because war was brewing. King Philip's War broke out in 1675. The Pennacooks strove to remain neutral, but even their Christianized members, known as "Praying Indians", came under English scrutiny. They fled north into the wilderness, only to be accused of treachery for running away. So they came back, although Wonalancet stayed up in the mountains. During their absence, they were ministered to by one of Eliot's assistants, Symon Beckham. When questioned by colonial authorities what they did out there in the woods, Beckham replied that "We kept three Sabbaths in the woods." "The first Sabbath," Beckham said, "I read and taught the people out of Psalm 35; the second Sabbath from Psalm 46; and the third Sabbath, out of Psalm 118." Beckham's listeners, all being versed in the Bible, no doubt understood the intimations of this Christian friend of the natives. Psalm 35 begins "Plead my cause, O Lord, with them that strive with me: fight against them that fight against me./Take hold of shield and buckler, and stand up for mine help." Psalm 46 begins "God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble/Therefore will not we fear, though the earth be removed, and though the mountains be carried into the midst of the sea." And Psalm 118 starts "O give thanks unto the Lord; for he is good: because his mercy endureth for ever./Let Israel now say, that his mercy endureth for ever." (All quotes are the King James version, which would have been used by the Puritans.) According to Major Gookin, on whose book this account is based, such Bible verses "were very suitable to encourage and support [the Wamesits] in their sad condition; this shows, that those poor people have some little knowledge of, and affection to the word of God, and have some little ability (through grace) to apply such meet portions thereof, as are pertinent to their necessities." Alas, being preached to did not help them. The natives were immediately blamed for burning down a barn in Chelmsford. Upon their return to Wamesit, this led to a skirmish with Chelmsford settlers, who killed a native boy and wounded five natives. Thereupon they wrote a pitiful letter to the government of Massachusetts: "The reason we went away from the English, for when there was any harm done in Chlemsford, they laid it to us and said we did it, but we know ourselves we never did harm the English, but go away peaceably and quietly. [As for the land reserved for our use], "we say there is no safety for us[,] for many English be not good, and maybe they come and kill us, as in the other case. We are not sorry for what we leave behind, but are sorry the English have driven us from our praying to God and from our teacher, Mr. Eliot. We did begin to understand a little [about] praying to God." No help came, so they left for the Pennacook headquarters, in present-day Concord, N.H. "On [Thursday,] February 6, 1676, having taken to the woods in search of Wonalancet, having lost their way and many lives by hardship and starvation." Even their retreat did not help. "[T]he English marched on Pennacook (Concord, NH). Wonalancet learned of their approach and led his followers into the swamps and marshes, where, from behind trees, they could watch every move of the whites. The soldiers destroyed their wigwams and winter's supply of dried fish. Wonalancet did not check the march of his refugees until the headwaters of the Connecticut River had been gained. Then only did they settle down, far from English wrong-doers, yet ever facing death, for the winter was a terrible one." (Charles Edward Beales, Jr. (pseud.), "Passaconaway in the White Mountains", 1916) In September 1676, the band of Wonalancet's followers were lured into a peace treaty with the English representative, Captain Richard Waldron, at modern day Dover, New Hampshire. The upshot of Captain Waldron's deception, which will be covered in another blog entry, was that over four hundred Pennacooks were captured there and then were sold into slavery in Barbados to help cover English expenses for the war. According to the Beales book, here is how Wonalancet then lived out his days: "Many tribesmen now abandoned the unresisting Wonalancet and went to the French at St. Francis [the present-day Abenaki reservation Odanack, Quebec]. By order of the Court, the decimated Pennacooks were transferred to Wickasaukee and Chelmsford, where they were under the supervision of Mr. Jonathan Tyng of Dunstable. Of the later years of Wonalancet's life little is known, until 1685, when, upon report of his 'fierce and warlike' presence at Pennacook, [this being his nephew Kancamagus leading the Androscoggins in revenge against Captain Waldron], he came to Dover, where he assured the government of New Hampshire (which now had become a Royal Province) that there were at Pennacook only twenty-four Indians beside squaws and papooses, and that this paltry band had no intention of making war upon the English. His name is not affixed to the treaty of this year, which seems to prove that he was no longer the recognized leader. Four years later, in 1689, he repeated his assurances of peaceful intentions. He is said to have again returned to St. Francis shortly after. Nine years later, he was again living under the care of Mr. Tyng, this time at Wamesit. The old sachem is reported as having transferred his lands, the last of his once vast domain, to his keeper. Deeds bearing dates of 1696 and 1697 are found, made out to Mr. Tyng. Whether he went back to St. Francis or died in his own country is not definitely known; the time of his death also is unknown. He is believed to have been buried in the private cemetery of the Tyng family, in Tyngsboro, Mass." Below is a summary of the Praying Towns closest to Boston (for Pennacooks and affiliated bands), followed by a summary of the Praying Towns in Worcester County (where the tribe was the Nipmucks).

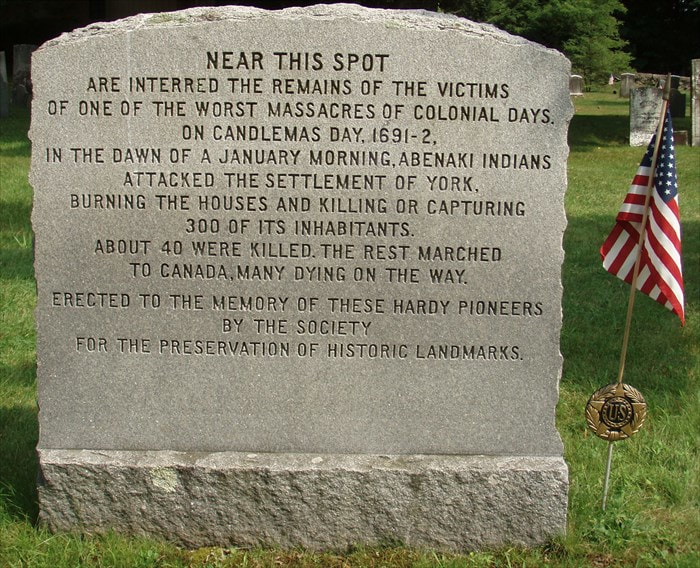

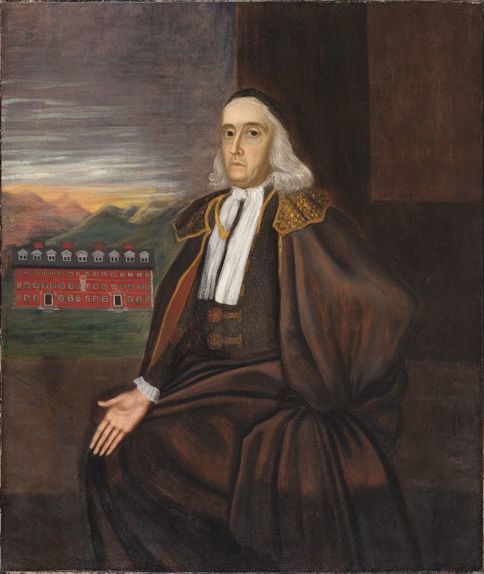

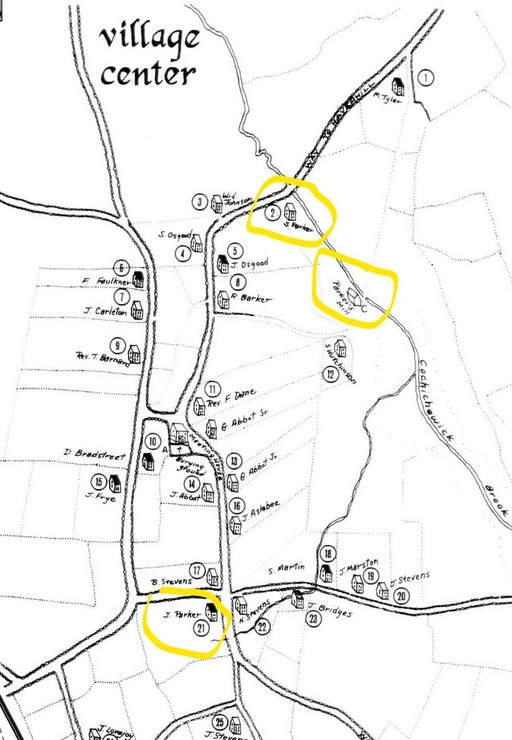

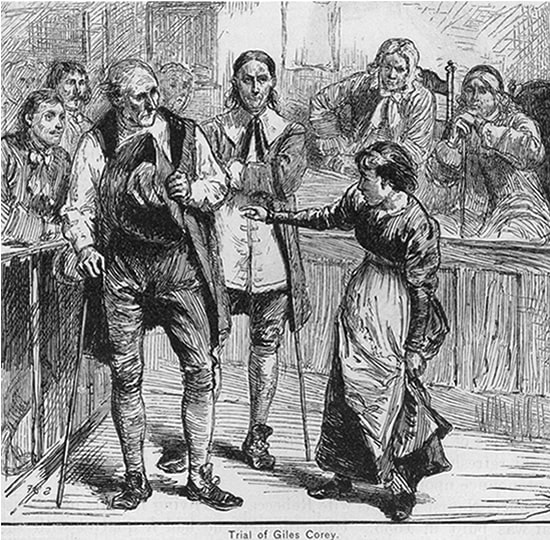

It is from “Biography and History of the Indians of North America: From Its First Discovery” by Samuel Gardner Drake (1848). The reference to Gookin was to Major-General Daniel Gookin, Commissioner of Praying Towns from the 1650s through the 1670s. “Natick, the oldest praying town, contained, in 1674, 29 families, in which perhaps were about 145 persons. The name Natick signified a place of hills. Waban was the chief man here, "who,"says Mr. Gookin, "is now about 70 years of age. He is a person of great prudence and piety : I do not know any Indian that excels him." Pakemitt, or Punkapaog ("which takes its name from a spring, that riseth out of red earth,") is the next town in order, and contained 12 families, or about 60 persons. It was 14 miles south of Boston, and is now Included in Stoughton. The Indians here removed from the Neponset. Hassanamesit is the third town, and is now included in Grafton, and contained, like the second,60 souls. Okommakamesit, now in Marlboro, contained about 50 people, and was the fourth town. Wamesit, since included in Tewksbury, the fifth town, was upon a neck of land in Merrimack River, and contained about 75 souls, of five to a family. Nashobah, now Littleton, was the sixth, and contained but about 50 inhabitants. Magunkaquog, now Hopkinton, signified a place of great trees. Here were about 55 persons, and this was the seventh town. There were, besides these, seven other towns, which were called the new praying towns. These were among the Nipmucks. The first was Manchage, since Oxford, and contained about 60 inhabitants. The second was about six miles from the first, and its name was Chabanaktongkomun, since Dudley, and contained about 45 persons. The third was Maanexit, in the north-east part of Woodstock, and contained about 100 souls. The fourth was Quantisset, also in Woodstock, and containing 100 persons likewise. Wabquissit, the fifth town, also in Woodstock, (but now included in Connecticut,) contained 150 souls. Packachoog, a sixth town, partly in Worcester and partly in Ward, also contained 100 people. Weshakim, or Nashaway, a seventh, contained about 75 persons. Waeuntug was also a praying town, included now by Uxbridge; but the number of people there ill not set down by Mr. Gookin, our chief author.” The Praying Towns were largely abandoned following King Phillips War, 1675-78, the first large-scale violence between English settlers and natives. Growing up I went to Littleton a lot, as well as Tewksbury. Never heard of Praying Towns even though the little ski area in Littleton, Nashoba Valley, bears the name of one of them. (A long read)Above: Monument to Mary Ayer Parker, Salem, Mass. Source: Find-A-Grave Background By the end of 1678, the first major episode of violence between natives and English colonists was over. Nearly 10% of the English population was killed in this King Philips War, but it was even more destructive for the natives. The eradication of the Narragansett and Wampanoag tribes and the weakening of the other tribes in the settled parts of New England did not mean the threat of Indian invasion disappeared, however. Instead, for the towns along the northwestern frontier of English settlement of North America – places like Haverhill and Andover – the threat actually grew. This is because the remaining natives became proxies in the rivalry between global empires, France and England. Some Indian groups had historically plundered the coastal tribes of New England...for example, the Mohawks from west of the Hudson, and the Ohio Valley-based Iroquois. Members of both tribes became paid mercenaries along the English-French frontier, in what is now Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont. Other tribes were fighting back against the encroaching devastation of their native lands. The Abenaki entered into a formal political alliance with the imperial government of France, seeking an established place in “Arcadia”, which was the colony of New France that extended from the present Canadian maritime provinces all the way down to the Kennebec River. Members of all three tribes became a threat to settlements of the puritan English frontier. Disruption to Lower Merrimack Valley and Northern Essex Region The first imperial proxy war became known as King William’s war, named after the distant English king, William of Orange, a newcomer from Holland who along with his wife Mary had inherited the English throne after the demise of the house of Stuart. He led a coalition of kingdoms against France. The opening volley in our part of the world was an attack directed by the governor of the Province of New England, who in 1688 organized a militia raid on the de facto French military leader of Arcadia, Jean-Vincent d'Abbadie de Saint-Castin, at what is now Castine, Maine, the southern-most point of French settlement. Saint-Castin was married to a Penobscot Indian princess and commanded mainly an army of Indians, aided by Jesuit priest-soldiers. This attack on Saint-Castine triggered war in the region. Abenakis and their French allies retaliated by targeting English settlements far down the Maine coast. They attacked Kennebunk in September of 1688; Salmon Falls (now Berwick) Maine in March 1690 (in which about 90 English villagers were killed or imprisoned for ransom); Wells in June 1691; and York in January 1692 (the so-called Candlemas Massacre in which 300 English villagers were killed or imprisoned for ransom). As a result of these devastating raids, dozens of English families fled southward into the relative safety of the Merrimack Valley and Essex County, past the warring tribulations of Kangamagus, last of the great Pennacook chiefs, near Dover. Below: Memorial to the victims of the Candelmas Massacre, January 24, 1692, York, Maine The refugees mainly swarmed Salem -- divided into Salem Town, now Salem, and Salem Village, now Danvers-- Ipswich, Haverhill and Andover. This influx of refugees strained resources and is thought to have contributed to the social unrest in these areas that caused “witch fever” to take hold. Although the hangings and other executions were centered in Salem Town, the most accusations of witchcraft apparently occurred in Andover, on the frontier twenty miles inland on the banks of the Merrimack. Andover had already suffered one Indian raid in August 1689, when the Peters house was burned and two persons were killed, so paranoia and apprehension likely ran high. Andover in the late Seventeenth Century The frontier region of northern Essex County in the late 1680s and early 1690s barely resembled the wilderness encountered fifty years earlier. Land had been allocated and cleared, and native trails became roads. Tight clusters of wood frame houses surrounded a parish meetinghouse; when the population grew too numerous, residents built houses far away from the meetinghouse. The road to Boston (present-day Route 28) and the road to Salem Town (present day Route 114) were bustling with trade at times, as grain, produce and timber made their way to market; and smoked fish, molasses from the rum trade, and finished goods made from England their way back to the hinterlands. Small boats could make their way up the Merrimack to Haverhill, site of the first falls, called Pentucket by the natives. Grist mills and lumber mills lined the streams, and tanneries and cottage industries provided basic clothing material, with the rest - such as cotton – shipped in through Boston and Newburyport. Despite the prosperity and relative stability of towns like Andover and Haverhill, the threat of Indian raids caused a general tone of apprehension. “The Indians were enemies very much dreaded. They concealed themselves and lay in ambush, and waited long and patiently, for an opportunity to surprise their prey. They never made their attacks openly, nor fought in the open field. The time of assault was often just before dawn of day, when they could strike the blow without resistance, and could cause the greatest panic. The inhabitants did not feel safe in their fields, and were liable to be shot down while at their labor. They frequently carried their firearms with them to their work. They also carried their guns when they assembled for worship on the Sabbath, and were exposed to be way laid in going and returning, and assaulted in the meeting house. They could not rest safely in their beds, without constant watch in time of war. They knew not when the enemy was near; they encamped in the wilderness, and were in the same place only a short time. It was as difficult to hunt them in the forest, as to hunt a wolf, and they were skillful at lying at ambush for their pursuers. Under such circumstances, the early settlers suffered exceedingly, not only from actual assaults, but from alarms and constant apprehension of danger. Their labors were often interrupted, much time was lost, and much expense incurred in securing their families and property. They were exposed, and suffered frequent losses, by destruction of their cattle, horses and barns, and pillage of their fields.” From The History of Andover, Mass. to 1829, by Ariel Abbot (1830). Thus there were grumblings about safety in the face of the obvious threat of Indian attack; however, nothing was done to form new parishes and build new meetinghouses and therefore form defensible new villages until a few decades later. Instead, newer residents lived far afield, in lone houses, on the edge of ancient forests that had yet to be cleared – rocky glacial soil made field clearance a slow and arduous task. Homes were timber frame, built using communal efforts, and covered either with clapboard, shingle or thatch-and-waddle. Some homes were built as “garrison houses” – brick in construction, with small windows that could be shuttered to keep out Indians and resist flame. One such house, the Peaslee Garrison House in East Haverhill, still stands today and was constructed around 1675 by my ninth great grandfather Joseph Peaslee [aka Peasley]. Above: Peasley Garrison House, East Haverhill, Built 1675 (now a private residence). Photo by the author. Similar garrison houses were erected on the periphery of Andover. Religious changes were evident too, causing further strain. The first two generations of New England puritans had been staunch believers, ready to sign up to covenants with their local puritan Meetinghouse vowing pure and virtuous life. Calling the churches “meetinghouses” signified the complete merger of religious life with civic life; all local governance took place within its walls. The right to vote in the local community was tied to membership in the church, which was limited to the elect who had undergone conversion by faith. But by the third generation, in the 1660s, there was a crisis. Were the grandchildren of the puritans who made the perilous journey to the new world presumed true believers? Or did they need to undergo their own personal “conversion”? A compromise was reached – they could sign up for a “half-way covenant”, in which, despite lacking a conversion experience, they could attend worship, but not receive rights to vote. This was the beginning of separation of local church and local government. By the 1690s, we were on the fourth generation, and church membership was plummeting… along with control of mores in the community, said the ministers. Yes, heresies in Boston had been dealt with, such as the expulsion of the Baptist Roger Williams to Providence plantation in 1636, the expulsion of Anne Hutchinson to New York in 1642 and the hanging of Quakers in Boston in the 1660s. However, apathy and alienation were harder to combat than zealous heresy. This was the context of the Salem witch trials. In addition to being the result of social strain wrought by King William’s War, the expansion of witch hysteria arguably represented an attempt by puritan leaders to use the situation to impose moral judgment. Sentences in the witch trials were handed down by William Stoughton, former puritan minister turned politician, who allowed most of the cases to be heard on the basis of spectral evidence: claims by witnesses of supernatural sensations. The court, after handing down its first execution in June 1692, adjourned to obtain advice of leading puritan ministers, who rallied behind the court’s purpose. The primary point of advice of the minsters was for the court to bring utmost help to those suffering molestations from the invisible world, by “speedy and vigorous prosecution of such as have rendered themselves obnoxious.” Below: William Stoughton, the Hanging Judge of the Salem Witch Trials, sitting in front of Harvard College, the seat of learning for the puritan ministry (Source: Wikipedia) Witches in the family John Ayer, the paterfamilias of all the Ayers in Haverhill and surrounding towns and my tenth great grandfather, passed from this mortal plane in 1657, in Haverhill. He left at least seven surviving children. His wife Hannah lived until 1688, dying at a ripe old age. By some accounts she was more than a hundred when she passed. John Ayer’s inventory upon death included “fower [four] cows, two steers, and a calf; twenty swine and fower pigs; fower oxen; one plough, two pair plough irons, one harrow, one yolke and chayne, and a rope cart; two howes, two axes, two shovels, one spade, two wedges, two betell rings, two sickels and a reap hook hangers in the chimneys, tongs and pot hooks; two pots, three kettles, one skillet, and frying pan in pewter; three flocks, beds, and bed clothes; twelve yards of cotton cloth, cotton wool, hemp and flax; two wheels, three chests, and a cupboard; ‘wooden stuff belonging to the house’; two muskets and ‘all that belong to them’; some books; some meat [presumably cured] about ‘fo[t]rie bushells of corne’; his wearing apparill; about six or seven acres of grain in and upon the ground; the dwelling house and barne and land broken and unbroken with all appurtenances forks, rakes, and other small implements about the house and barne.” Thus, he prospered in the new world. Their son Robert, my ninth great grandfather, was designated a freeman in 1666, made a selectman in 1685, and was known as sergeant of the local militia after 1692. He was even more prosperous than his father, whereas the refugees and other newcomers had virtually no possessions, eking out existences as boarders and field workers. Witchcraft came to the Ayer family when Robert’s sister, Mary Ayer Parker, of Andover, was accused of witchcraft in early September 1692, six months into the witch craze. She was hanged by the end of that month, proclaiming her innocence until her death. Mary had been married to Nathan Parker, a former indentured servant who had settled in Newbury with his brother Joseph sometime in the 1630s. By 1648, Nathan had bought his freedom and was living in Andover, as one of its first settlers. His first wife died, and within a few months he married Mary Ayer. The original size of Nathan Parker’s house lot was four acres but his landholdings improved significantly over the years to 213.5 acres. His brother Joseph, a founding member of the meetinghouse in Andover parish, possessed even more land than his brother, increasing his wealth as a tanner. By 1660, there were forty household lots in Andover (clustered around what is now North Andover common, the original village of Andover), and no more were created. Subsequent landholders built their homes far afield, near their farms. By 1650, Nathan began serving as a constable in Andover. Nathan and Mary had their first child, John, in 1653. Mary bore four more sons: James in 1655, Robert in 1665, Joseph in 1669 and Peter in 1676. She and Nathan also had four daughters: Mary, born in 1660 (or 1657), Hannah in 1659, Elizabeth in 1663, and Sara in 1670. Her son James died on June 29, 1677, age twenty-two. He was killed in a battle with Indians at Black Point, in what is now Scarborough, Maine, in one of the last skirmishes of King Philips War, along with his cousin John Parker (son of his father’s brother Joseph Parker), who had fought in the Great Swamp campaign in Rhode Island a few years previous. Nathan Parker, husband of Mary Ayer Parker, died in June 1685. He left an estate valued at 463 pounds – more than double the estate of his father-in-law John Ayer – and a third of it went to Mary his wife. It is not known what her lifestyle was like after 1685; however, she was likely living alone as all her children were grown and all the girls were married by this time and living in their own homes. Below: detail of map of Andover [now North Andover common] in 1692 prepared by the North Andover Historical Society. It's not clear which residence would have been Nathan Parker's. The accusation of witchcraft against Mary Parker She was accused by fourteen-year-old William Barker Jr. in his confession on September 1, 1692. Young William’s father, William Sr., and his thirteen-year-old cousin Mary Barker, daughter of the deacon of the Andover meetinghouse, had already been imprisoned for witchcraft three days earlier. The accused William Jr. stated that he had so recently converted to witchcraft that he “had only been in the snare of the Devil for six days.” He testified that "Goody Parker went with him last Night to Afflict Martha Sprague." Goody was an abbreviation of goodwife, a title used for most married women in puritan Massachusetts. Young William elaborated that Goody Parker "rode upon a pole & was baptized [by Satan] at Five Mile pond." [Now called Haggetts Pond] The examination of Mary Ayer Parker occurred the next day. At the examination, afflicted girls and young women from both Salem and Andover fell into fits when her name was spoken. These witnesses included Mary Warren (a twenty-year-old servant), Sarah Churchill (a refugee from Saco, Maine), Hannah Post (a twenty-six year old whose father Richard had been killed by Indians), Sara Bridges (Hannah Post’s seventeen year old stepsister), and Mercy Wardwell (age nineteen, already under arrest for witchcraft, daughter of wealthy Samuel Wardwell of Andover, who was eventually hanged for witchcraft the same day as Mary Parker). The records state that when Mary came before the justices, these girls and young women were cured of their fits by her touch, which was the satisfactory result of the commonly used "touch test," signifying a witch's guilt. Below: A witness performing the touch test on Giles Corey, accused of witchcraft Mary Ayer Parker was tried in Salem. During her examination she was asked, "How long have ye been in the snare of the devil?"

She responded, "I know nothing of it.“ Her defense was mistaken identity: other Mary Parkers lived in Andover – by whom she would have meant either her brother-in-law Joseph Parker’s wife Mary, nee Stevens, or their daughter. It was not clear why she would have tried to throw her relatives ‘under the bus’ (to use an anachronistic phrase). Perhaps there were still hard feelings over the death of her eldest son James after he followed their son John, his first cousin, into war against the Indians. In any case, the court did not buy her defense. Like most accused in the witch trials who protested their innocence rather than confessing being in league with the devil, she was found guilty and hanged. Conclusion Some people think the witch trials were purely the result of the belief systems of the Massachusetts puritans. However, they came into existence at a time of great social stress, as refugees fleeing horrifying Indian raids along the Maine frontier upset the social order of towns like Andover and Salem where they sought shelter. The belief system of the Puritan ministers became a weapon that could be used in a form of class warfare, in which the marginalized could bring down their superiors, especially ones haughty enough not to admit they were in fact witches. Statute in Edson Cemetery, Lowell, Mass. depicting Passaconnaway The town of Haverhill was founded by charter of the General Court of Massachusetts in 1640 but title was not transferred until November 15th, 1642, when the great chief of the Pennacooks, the native inhabitants of the entire valley of the Merrimack from Pentucket (later called Haverhill) up to the river’s highest headwaters, transferred twelve miles of land along the river to form Haverhill.

Pasaconnaway had been an impressive leader with magical powers. According to one early English account, “Hee can make water burne, the rocks move, the trees dance, metamorphise himself into a flaming man. Hee Will do more; for in Winter, when there are no green leaves to be got, hee will burne an old one to ashes and putting these into water, produce a new green leaf, which you shall not only see but substantially handle and carrie away; and make a dead snake's skin a living snake, both to be seen, felt, and heard.” Under his leadership, the Pennacooks, whose name aptly means ‘rocky place’ tribe, subsumed the neighboring tribes, the Wachusetts, Agawams, Wamesits, Pequawkets, Pawtuckets, Nashuas, Namaoskeags, Coosaukes, Winnepesaukes, Piscataquas, Winnecowetts, Amariscoggins, Newichewannocks, Sacos, Squamscotts, and Saugusaukes. Alas, the sale of Pentucket (Haverhill) to a group of Englishmen was one of the last historical acts of the Pennacooks. In the devastating war between the English and the natives in 1675– called King Phillip’s War after the Anglo nickname of native leader, Metacom, a Wampanoag from south of Boston – the Pennacooks sought to remain neutral. For safety during the conflict, they largely retreated to their mountain fastness near the headwaters of the Merrimack river high in the White Mountains. The Pennacooks came under suspicion and, upon their return to the lowlands at the end of the war, hundreds of their braves were captured en masse in a treacherous maneuver orchestrated by Captain Richard Waldron. This occurred at the Indian trading post in Dover, New Hampshire, known by the natives as Cocheco. Some of the Pennacook men were hanged for insurrection and the rest were sold into slavery in Barbados. The few remaining members of the tribe began to abandon Passaconnaway’s leadership. They retreated far to the north, to the mouth of the Saint-François River at its confluence with the St. Lawrence, to the reservation established by the French in Quebec, called Saint Francis in English. Today it is still a reservation, called Odanak, home of four hundred Abenaki with whom the Pennacooks merged. The great king Passaconnaway, a.k.a. Papisseconeway, a.k.a. Saint Aspenquid, died in 1682. The few remaining Pennacook warriors bore his body to the summit of Mount Agamenticus, it was said, and laid him to rest in a rocky cave. The alternative and more compelling story is that he was buried at the summit of Mount Agiocochook, now called Mount Washington, the highest mountain in New England, near the headwaters of the Pemigewasset River, itself the northernmost tributary of the Merrimack. Or his body was not borne there at all; rather he ascended there himself like Jesus Christ, whom many of the Indians had adopted by that time as their great spiritual leader. “There was to be a Council of the Gods in heaven and it was Passaconaway's wish that he might be admitted to the divine Council Fire; so he informed the Great Spirit of his desire. A stout sled was constructed, and out of a flaming cloud, twenty-four gigantic wolves appeared. These were made fast to the sled. Wrapping himself in a bearskin robe, Passaconaway bade adieu to his people, mounted the sled, and, lashing the wolves to their utmost speed, away he flew. Through the forests from Pennacook[modern-day Concord N.H., his royal seat]and over the wide ice-sheet of Lake Winnepesaukee they sped. Reeling and cutting the wolves with his thirty-foot lash, the old Bashaba, once more in his element, screamed in ecstatic joy. Down dales, valleys, over hills and mountains they flew, until, at last, enveloped in a cloud of fire, this ‘mightiest of Pennacooks’ was seen speeding over the rocky shoulders of Mount Washington itself; gaining the summit, with unabated speed he rode up into the clouds and was lost to view―forever!” Charles Edward Beals, Jr., Passaconnaway in the White Mountains, 1916. Thus basically ends the story of the Pennacooks, except for the place names they gave. Mount Passaconaway (4,043 ft.) is named for their leader. Mount Wonalancet (3,200 ft.) is named for his son. The Nanamacomuck Trail is named for his other son. The Kancamagus Highway is named for Passaconnaway’sgrandson, son of Nanamacomuck, who in 1689 led a brief and final Pennacook rebellion against the English. It was mainly fought not by Pennacooks but by “a throng of restless and vengeful Androscoggins.” Their crowning accomplishment was to murder the elderly Captain Waldron, who had sold so many of their kinsmen into slavery four decades earlier. The Pennacooks also left us with the names of most of the various tributaries of the Merrimack River: Contoocook (Near the Pines), Squannacook (Green Place), Suncook (Place of Villages), Piscataquog [or Piscatacook] (Great Deer Place), Souhegan (Waiting and Watching Place), Shawsheen (Serpentine), Quinepoxet (Pebbled Bottom). “The great, numerous, and powerful Pennacooks, where are they? Two hundred years have effaced every vestige of the race; they are rubbed out like a chalk mark on a black-board ; every trace of the blood is obliterated; no scion remains; they have withered as the grass beneath the pavement, and the places that knew them once shall know them no more forever. The few fragile and broken remnants of the race, dispirited, and dimly realizing their ultimate doom, long since turned their backs on old· familiar scenes, on the conqueror, and their faces to the setting sun, where year by year his domain is curtailed, and himself more closely environed, until, at no very distant day, he will be totally and finally obliterated from the face of this broad land, and become as much of a myth or tradition, as the centaur, the mastodon, or the sphinx.” J. W. Meader, The Merrimack River: Its Source And Its Tributaries (1869) His son Wonalancet, his daughter Wenunchus and his grandson Kancamagus have their own interesting stories covered in other blog entries. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed