|

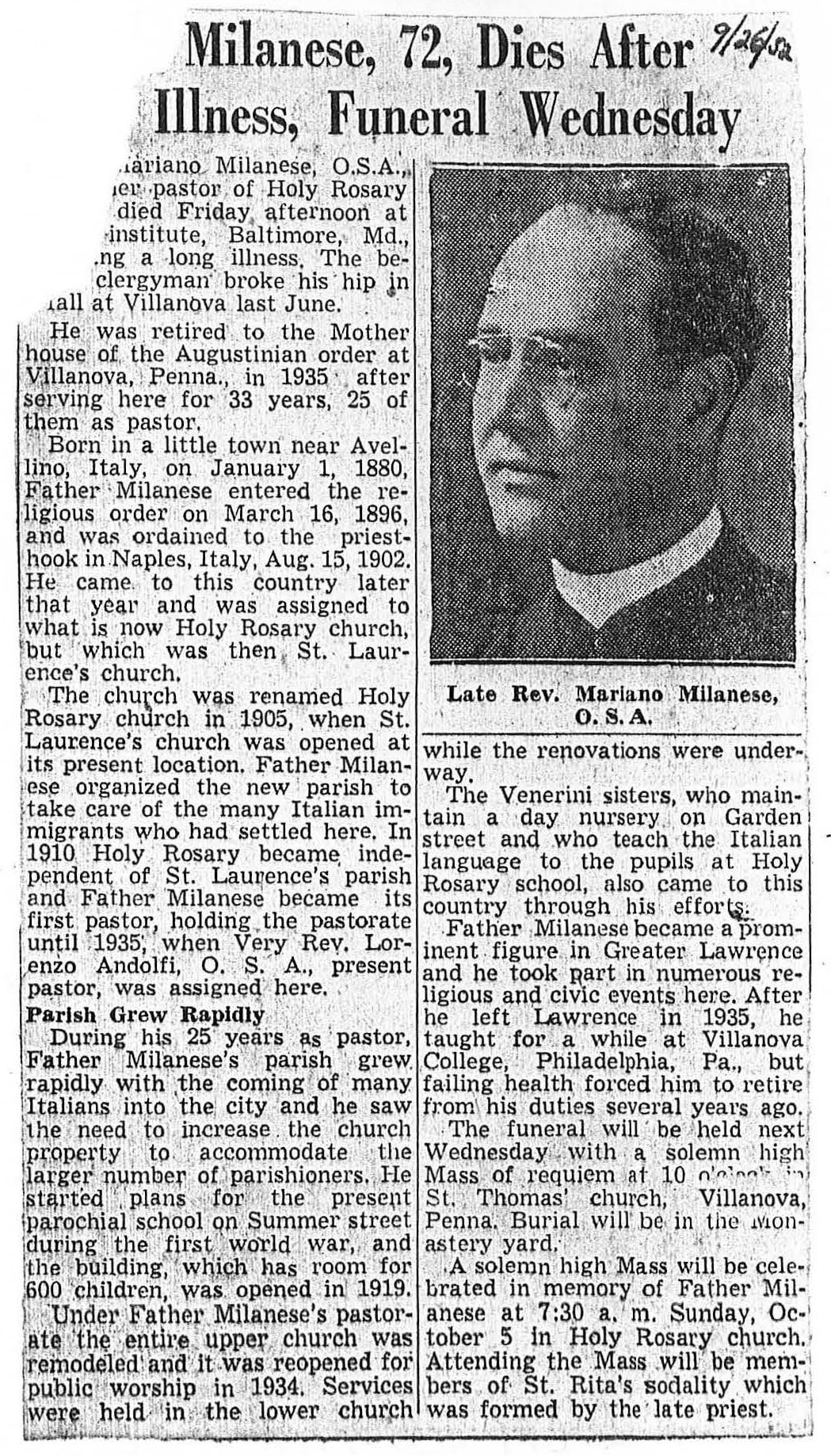

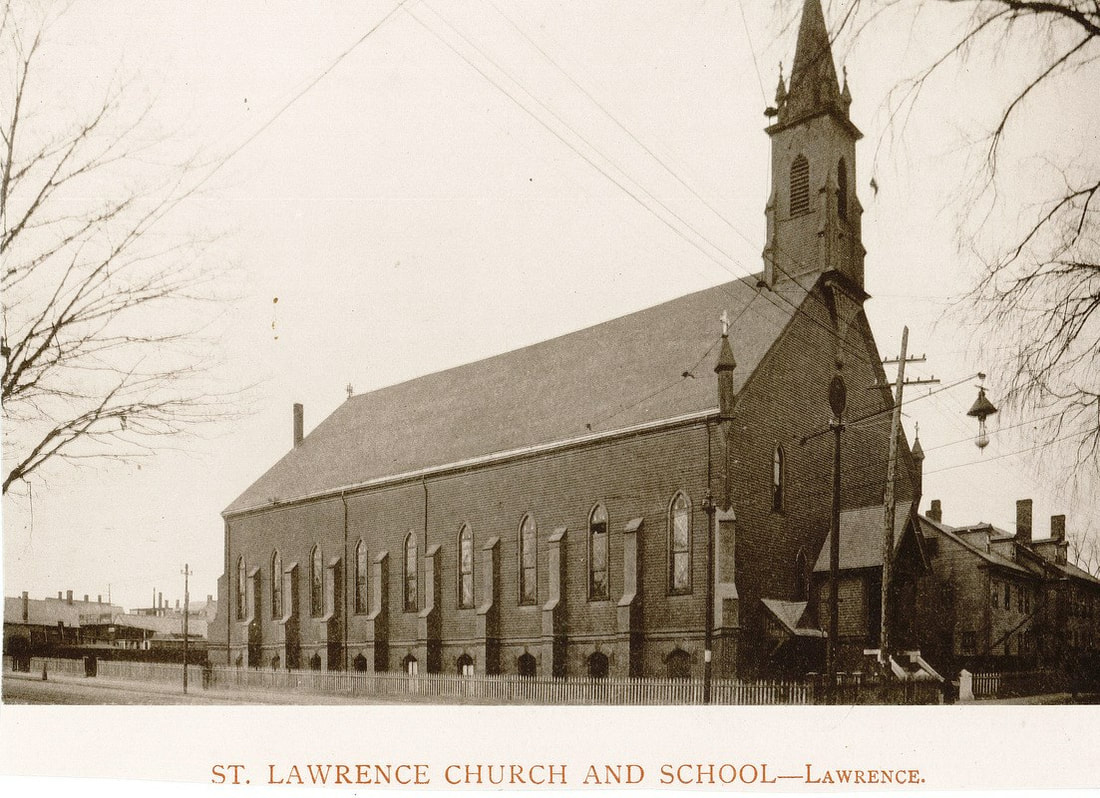

Above: The 1952 obituary of Father Milanese in the Lawrence Tribune. (Source: Lawrence History Center) The obituary of the priest who founded Holy Rosary seems to give all relevant details - name, dates, background and accomplishments, such as remodeling the church, founding the school, forming St. Rita's sodality and bringing nuns from Italy. What else is there to say? It turns out, a lot. Father Milanese showed up in Lawrence in 1902 at the age of twenty two during a time of great change. Italian immigrants were pouring in. They were unknown in Lawrence before the 1890s. Prior to that time, Lawrence was a mixture of Irish, French-Canadian and a little bit of old New England. In accordance with the "national parish" policy of the Catholic Church of that era, these immigrants needed their own Italian Church, just as contemporaneous Polish, Lithuanian and Portuguese immigrants would soon also each get their own nearby Polish, Lithuanian and Portuguese national parishes. The first St. Laurence O'Toole church, which became Holy Rosary in 1905. Top photo: When it was still St. Laurence O'Toole around 1900 before that parish moved to East Haverhill Street. Bottom: Contemporary photo of the church. Today it is Corpus Christi parish following the 2004 merger of the four parishes in the area. Milanese's changes to the facade and steeple (described below) are apparent. Accordingly, when the old St. Laurence O'Toole church, built on the corner of Union Street and Essex Street in 1873, planned to move to a new structure on East Haverhill Street, its building became available. Milanese was already a pastor there, ministering to Italians in the so-called basement chapel where homilies could be given in Italian. He had replaced Father Guglielmo Repetti, who gave the first masses there in Italian in 1899 and who had died suddenly. Milanese seemed to be the perfect leader for the new parish, which he named Holy Rosary. He was a young, energetic institution builder, in the mold of the young Irish priests who had founded the first Catholic churches in Lawrence two generations earlier. However, by these years, the Catholic hierarchy did not necessarily want a pragmatist who got things done for the benefit of his flock. They forgot their own roots bootstrapping the Church in the USA up from nothing in the 1850s. Instead, they wanted someone who towed the line, especially Cardinal O'Connell, archbishop of the Boston diocese. Under his authoritarian leadership, he centralized all decision-making and drastically reduced the autonomy of individual parishes. The conflict between Milanese and O'Connell over finances was eventually the Italian priest's undoing. The story of Milanese's pastorate - from which he was forcibly removed in 1935 - is one of trying to do what was best for his flock of recent Italian immigrants, despite limitations placed on him by his community and the Irish-dominated local Catholic hierarchy. Photo below (1925): Father Mariano and boys of the Holy Rosary School, which he established in 1919 (courtesy of the Lawrence History Center) The Mezzogiorno, Campanilismo, and Italian immigration Mass immigration usually requires some catalyst - famine, war, poverty, political unrest. In the case of immigrants from the Mezzogiorno - the part of the Italian peninsula south of Rome all the way down to the tip of Sicily - the catalyst was the unification of Italy starting in the mid-nineteenth century and culminating in 1870. "Southern Italy (the Mezzogiorno), the source of more than 75 percent of immigration to the United States, was an impoverished region possessing a highly stratified, virtually feudal society. The bulk of the population consisted of artisans (artigiani), petty landowners or sharecroppers (contadini), and farm laborers (giornalieri), all of whom eked out meager existences. For reasons of security and health, residents typically clustered in hill towns situated away from farm land. Each day required long walks to family plots, adding to the toil that framed daily lives. Families typically worked as collective units to ensure survival..." "The impact of unification on the South was disastrous. The new constitution heavily favored the North, especially in its tax policies, industrial subsidies, and land programs. The hard-pressed peasantry shouldered an increased share of national expenses, while attempting to compete in markets dominated more and more by outside capitalist intrusions." (Source: https://www.everyculture.com/multi/Ha-La/Italian-Americans.html) Journalist Erik Amfitheatrof described the magnitude of the migration: “The exodus of southern Italians from their villages at the turn of the twentieth century has no parallel history,” he wrote. "Of total population of million the South time of national unification starting in 1860, least five million--more than third of the population--had left to seek work overseas the outbreak of World War. The land literally hemorrhaged peasants." Below: Painting "Leaving Italy for a Better Life" (Source: Wikipedia) One Italian writer described the scene as peasants departed from a rural town in Sicily, bound for Palermo and then America: “The locomotive whistled fitfully with a laboring hiss, but the disorder was so great that the engineer did not move the train. Despite the requests and the reprimands of the police, the crowd still clutched the train, embraced the final grasps of good-bye. When the train moved, there was heartbreaking cry like the anguished roar that bursts from crowd at the instant of a great calamity. All the people raised their arms and waved handkerchiefs. From the windows of the cars the leaning figures of the young men and women strained; they seemed suspended in air and kissed the hands of old people as the train departed.” That scene, repeated again and again in small villages and towns throughout Southern Italy, represented a decision of epic proportions by tens of thousands of Italian peasants, most of whom had never traveled more than a few miles from home. (From Italy to Boston's North End: Italian Immigration and Settlement, 1890-1910, by Stephen Puleo. Master's thesis, University of Massachusetts Boston) Migrants brought with them their family-centered peasant cultures and their fiercely local identifications, or campanilismo. In this first phase of immigration, they typically viewed themselves more as residents of particular villages or regions, and not so much as 'Italians.' The organizational and residential life of early communities reflected these facts, as people limited their associations largely to kin and paesani (fellow villagers). The proliferation of narrowly based mutual aid societies and festas (feste, or feast days) honoring local patron saints were manifestations of these tendencies. (Source: https://www.everyculture.com/multi/Ha-La/Italian-Americans.html) Indeed, in Lawrence, mutual aid societies sprang up, each focused on residents from a very specific region. By 1915, the following mutual aid societies were in existence, each with a local connotation:

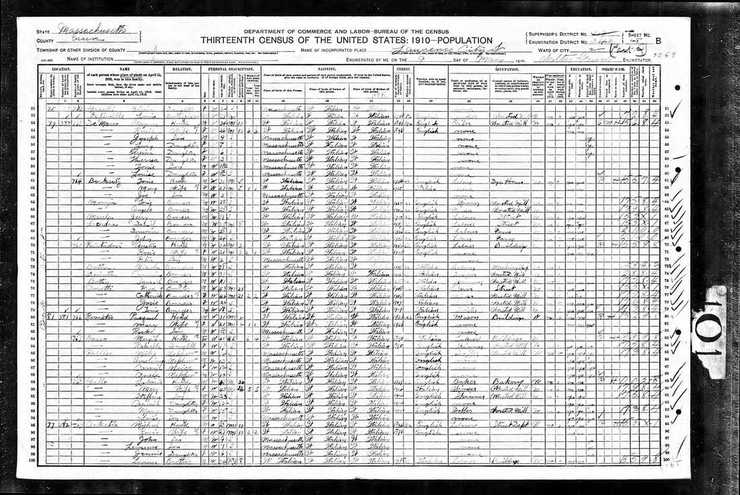

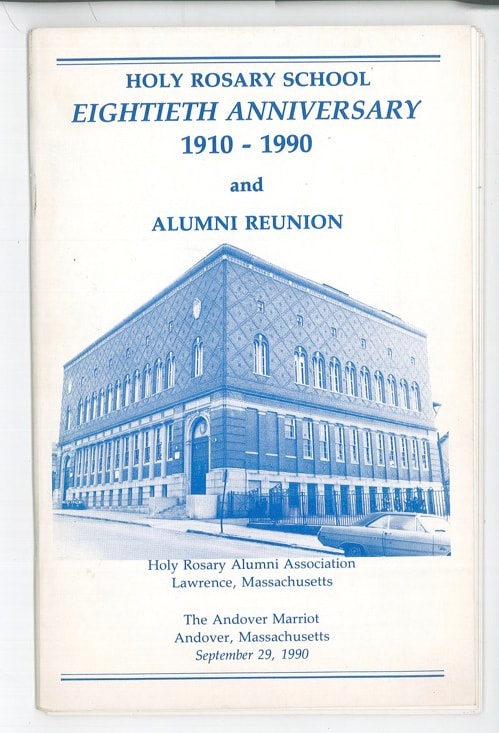

In Lawrence, immigrants from different regions stuck together. “Immigrants from Sicily and the far southern region of Calabria formed a four-block neighborhood, bounded by Essex, Union, Summer and Jackson streets. The newcomers from the Naples area settled in a smaller, adjacent colony on Chestnut, Elm and Oak Streets” (Source: The Education of an Italian Priest in America: Father Mariano Milanese and the Holy Rosary Church, Lawrence, Mass. 1902-1935 by Christopher Sterba in The Italian American Review Volume 7 Number 2 Winter 2000). "The enclave offered Italians a chance to make the transition from the Old World to the New. For those who were coming to America only temporarily, the enclave provided a secure, familiar setting without requiring returning Italians to make a heavy investment in assimilation. For those Italians who eventually decided to stay, enclaves provided a buffer against a harsh and strange American society. Enclaves helped ensure the survival of la via vecchza, “the old way”, which dictated a host of Italian family mores and social customs." (Source: Puleo) Below: A sheet from the Federal Census of 1910, showing a section of Oak Street. Note that every adult resident was born in Italy and all had arrived after 1894. Within these highly localized enclaves, local customs of the old villages continued, such as festas. Lawrence's Feast of Three Saints, devoted to three martyred brothers from Trecastagni in Sicily, is actually the newest of the street festivals, each catering to the particular traditions of a particular village. The first festival to be organized, the Feast of the Blessed Virgin of Pompeii, began in October 1903 when the Italian church was still the basement of then-St. Laurence O’Toole’s. Pompeii is village outside of Naples. According to the Lawrence Tribune, which reported the day after the Pompeii Virgin festival: “The stores and residences in the Italian section were appropriately decorated with American and Italian flags and gay bunting. Over 1500 lanterns were strung on Common street from Jackson to Union streets and they made a brilliant illumination when lighted at night.” Other festivals included St. Anthony, St. Joseph and St. Parade. (Source: Sterba) Below: Procession during the Feast of Three Saints, Lawrence, Mass. 2018 (video by the author). It is held next to the church. Father Milanese sets about making the ideal parish Father Mariano found himself in this world of campinalismo, local village loyalties and saints feasts - as well as a time of disintegration of traditional values and the rise of competing value systems, such as anarchism and communism, which had more than a few adherents among Italian workers of this time. In 1904, he purchased the old St. Laurence Church at the corner of Union Street and Essex Street, for about $31,000 using a loan from the diocese, and renamed it Holy Rosary as a church for Italian immigrants. The Italian population of Lawrence was growing exponentially, from 263 in 1890 to 963 Italian-born persons in 1900, still most of them men. By 1915, there were almost 9,000 Italian born persons and their American-born children. Father Mariano had to make sure they became churchgoers by providing them with impressive institutions that met their needs. However, because of challenges such as historically low levels of Italian participation in weekly Mass, anticlericism, competing value systems including communism and Protestant denominations, and an apparent preference for folk customs such as street festivals, it was far from guaranteed that all or most of the immigrants would be part of his church. This is why Father Milanese seems to have insisted on providing the best of the best in everything he did, regardless of expense. "For Milanese, the survival of an Italian parish in America and the Christian values it espoused depended on a physically impressive church worthy of city-wide respect. The parish had to symbolize prosperity and dignity; a well-defined path to security and welfare that would make secular and socialistic alternatives appear wholly inadequate in comparison." (Source: Sterba) Below: The interior of Holy Rosary (now Corpus Christi). Photo taken 1951. The challenges facing Father Mariano In contrast to immigrant groups such as the Irish and the Poles, for whom their Catholicism was central to their identity – perhaps as an institution of resistance against foreign subjugation – immigrants of the mezzogiorno often negatively associated the Catholic church as an institution with dominant and distant powers such as landlords, or tax collectors from Rome. Also, there was a deep seated anticlericism in parts of the population, in which priests were perceived as being motivated by little more than greed and corruption. Also, given that, in Italy, the state paid for the church there was no tradition of ordinary Italian parishioners supporting their local church with donations, the way there was among the Irish or Poles. Recall that St. Mary's Church, built in 1871, was essentially funded by thousands of tiny contributions from ordinary Irish parishioners, assisted by the "St. Mary's Bank", in which the church operated a deposit-taking savings bank. Instead, “The Italian Catholic church was considered a source of charity, not an institution that depended on its parishioners' low incomes. To make matters worse, Italian…parishioners came to them only for the ritualistic ceremonies they considered most important, the major sacraments--baptism, matrimony and last rites.” (Source: Sterba) Because churches largely had to be financially self-sustaining, these tendencies -- that existed at least initially among the immigrant population -- created enormous challenges for any priest trying to build and sustain a parish and all its institutions. Further, as Sterba noted, saint veneration societies actually competed with the parish for funds: "The societies were not parish organizations. They operated without the pastor's direction and, what was especially galling to the immigrant clergy, their collections were greeted with much more enthusiasm than parish fund-raising campaigns." Finally, the turn of the twentieth century was a time of great political and social change, especially in Italy. The country underwent a tremendous shift toward modernization, with the corresponding disruptions of a new industrial workforce. Many of the population were susceptible to the promises of Communism, or the intoxicating power of Anarchism in which the average man could violently assert himself against an oppressive system using bombings and assassinations. These tendencies reached their height at the time of the 1919 Lawrence Strike, but were also a big part of the 1912 Bread and Roses Strike, which was mainly comprised of recent Italian immigrants (my blog post on Italians and the 1912 strike is here). Father Mariano wanted to counter these challenges with a strong, impressive parish, saying so in a letter to the Archbishop: "The people were clamoring for a decent church and the congregation was getting bigger and bigger as time went on. Socialists, Anarchists and Communists were doing their best to influence my people and I wished this church as a means of welding my people together." His accomplishments “During the decade that followed the establishment of Holy Rosary Parish in May 1905, Father Milanese's responsibilities as pastor grew exponentially. The rise in the volume of normal priestly duties conducted by Milanese reflected this growth. In 1903, his first full year in Lawrence, the young priest performed baptisms for 137 Italian immigrant children; by 1915 he and his assistants at Holy Rosary recorded 765 baptisms. Milanese gave First Holy Communion to 20 Italian children in 1903; twelve years later Holy Rosary performed the sacrament for nearly 200. He also created a number of parish organizations, among them the Sodality of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Christian Mother Society, and Italian branches of the Young Men's Catholic Association and Holy Name Society. The religious and educational needs of his parishioners meanwhile demanded a dramatic expansion of Milanese's financial and administrative responsibilities. He was able to raise substantial funds for church repairs in 1906, and in 1910 spent over $20,000 to construct and furnish a parish house, office, and sacristy, and to build a gallery extension to the church and install a new organ. He spent $10,000 to refurbish the basement of the church for use as a school in 1909, and requested teachers from the Sisters of Venerini Order to begin classes for the city's Italian children. Seven Italian Venerini nuns arrived in Lawrence in November, and with the help of two lay teachers who taught English, grade school classes began in January 1910. In 1912, Milanese responded to the rising numbers of Italian school children by requesting the English-teaching services of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur, and in 1917 built a kindergarten for the Venerini Sisters to operate.” (Source: Sterba) His masterpiece was the Holy Rosary School. In 1915, Milanese purchased two houses on Summer Street and had them knocked down. Construction started in 1917 with a grandiose cornerstone ceremony. According to a July 28, 1917 article in the Lawrence Telegraph, “plans were perfected for the parade and ceremonies incidental to the cornerstone laying at the Italian school on Summer Street, Sunday afternoon, August 5 at 2 o’clock, and the Rev. Fr. Mariano Milanese expects that it will be one of the most edifying spectacles in the history of the city. There will be in the parade about 2000 people, representing the largest Italian organizations of the city.” The article then described all the luminaries who would be present at the laying of the cornerstone, including the priests from the (de facto Irish) churches of St. Mary’s, Immaculate Conception and St. Laurence O’Toole; prominent Italian-American doctors, lawyers and businessmen; and even well-known Protestants. It then describes the parade in grandiose terms, listing the exact formation of the parade by organization. The parade route was to be “Jackson street to Essex, to Union, to Common, to Lawrence, to Union, to Summer.” Representative organizations included numerous village-based mutual aid societies, such as the Societia Teanese [i.e. of Teano, a village near Naples], the Societia Tricacria [i.e. the symbol of the island of Sicily], and the Societia Lafiazi [anyone know what this is?], as well as the drum corps of Our Lady of the Rosary. In the construction of the school, no expense was spared. It had an ornate Italianate exterior decorated with columns and multi-toned brickwork. Inside, it featured state of the art technology, such as film projectors (in 1919!). It had fourteen classrooms, an auditorium and a basement. It cost a quarter of a million dollars. A celebratory pamphlet published for its dedication in November 1919 stated: "Truly such a beautiful school was never dreamt of by the people of Lawrence; and when it was seen, they were struck with bewilderment." Below: Image of the Holy Rosary school from a 1990 brochure. The school closed in 1994 and is presently abandoned. How Father Mariano funded his efforts, and his downfall At every step of the way, Father Milanese seems to have wanted Holy Rosary to be as nice a parish as possible, with grand institutions such as its school. Given the financial limitations he faced, he often had to resort to creative measures. In 1915, he got in trouble with the archdiocese for baptizing Polish and Lithuanian children from nearby churches, for a fee, when their priests were not available on desired dates. He was made to stop. In 1916, he incurred the anger of the archbishop for giving his homilies in English, in order to attract more English speaking parishioners, whom he could then ask for donations. He was made to stop. In 1918, when funds ran out for the construction of the Holy Rosary School, he secured a $50,000 donation from the Manufacturers' Association for Welfare Work, an organization founded by the major mills of Lawrence. "The city's manufacturers saw the Catholic school as an indirect means of subduing and Americanizing the future generations of Italians that would come to work in their mills." (Source for all of this: Sterba) "The manufacturers' contribution, kept secret from the public, was made possible through Milanese's close contact with William Wood, president of the American Woolen Company. Wood and the other owners provided a second large donation to Holy Rosary for the construction of a community building in November 1919." (Sterba) During the 1919 strike, Milanese railed against communists and anarchists in the Italian community, and criticized the government authorities for not silencing these voices. This is in contrast to his behavior in the 1912 Bread and Roses strike when, among all the priests of Lawrence, he was the most supportive. Sterba explains Milanese's later attitude: "Milanese's vision of prosperity and uplift for the city’s Italian population consisted of a strong and respected parish, a large parochial educational system, and church organizations that provided social and recreational services for the community. These institutions depended financially on a healthy and mutually supportive relationship with the mills where his parishioners labored. Conflict in the workplace therefore meant for him destructive community conflict, impoverishment, and a backward step in the Italians' struggle against prejudice and discrimination. But despite all of Milanese's anti-strike activities, Italians again formed a pro-union bulwark in 1919. The experience of this failure compelled Milanese to expand Holy Rosary's works even further, and completely ignore any financial confines that the Archdiocese imposed upon him." He continued to borrow and spend money to maintain Holy Rosary Parish in the most impressive manner. In 1925 , he paid $10,000 for a new steeple and roof, and murals for the school. In 1928, he conducted an enlargement and refurbishing project for the church, converting the basement back into a space for worship and making other improvements. In 1929, he embarked on a major beautification process for the upper part of the church. In 1928, he finally confronted the saints' societies, threatening to forbid their processions entirely unless they handed over all their collections to the parish. He ultimately came to a settlement where they agreed to contribute a sizable portion. He was in hot water for the entire period. The archbishop criticized him in 1925 for not paying down the mortgage, in 1926 for not getting his permission to make improvements, and in 1928 for having the nerve to ask for financial assistance for certain projects. The archbishop also criticized Milanese for using expensive stationary. Then in 1931, when contractors threatened to sue the archdiocese for unpaid bills, the wheels started to come off. "In October the Cardinal demanded that Milanese employ a certified public accountant to make a complete audit of the church's financial records. Although Milanese claimed that the parish owed just over fifty thousand dollars in each of his reports for the years 1927-1930, the accounting firm estimated that the church was an astonishing $212,246 in debt." Later investigations showed three sets of books - Milanese pleaded incompetence rather than malice - and additional debts based on handshake contracts. By 1934, the indebtedness of the parish was over $300,000. The defense for continuing to work on improving the church after money had run out was "it was the belief of all concerned that if the church were finished the Italians of the Parish would then help by their contributions." "The congregation had frequently stated that they would contribute nothing toward the church" until all work was completed. (Sterba) Father Milanese was relieved of his duties in July 1935, moving to Villianova, the Augustinian college. He retired from the priesthood in 1937, and lived in a nursing home until his death in Baltimore on September 26, 1952. Legacy of Father Milanese In 1935, the corporate arm of the Augustinians in Lawrence, the St. Mary's Corporation, assumed the debts. They were in effect paid off by all the churches of Lawrence that were Augustinian (St. Mary's, Immaculate Conception, St. Laurence O'Toole, St. Augustine's, Holy Trinity, St. Francis, Ss. Peter and Paul, Church of the Assumption and Holy Rosary). The improvements to Holy Rosary church were completed, making it one of the most impressive churches in Lawrence. In my view, Milanese was unfairly treated. He very much resembled the first Augustian priest of any standing in Lawrence, Father James O,Donnell, whose mission in the 1850s was to see to the construction of the grand St, Mary’s church and the creation of schools. He used whatever financial means he could find to achieve his goals. By Father Milanese’s time, the powers-that-be had forgotten that Father O’Donnell’s clever solution, the “St Mary’s Bank”, had eventually failed in 1882. It had to be bailed out by the diocese because it couldn’t pay its debts that had been incurred in constructing the first wave of (essentially Irish) churches. (Source: Ennis, No Easy Road: The Early Years of the Augustinians in the United States). Above: Father Lorenzo Andolfi. Source: Website of the Augustian Order The much-beloved Father Lorenzo Andolfi assumed the pastorate of Holy Rosary in 1935, and remained there until his death in 1962. He successfully led his parish through a time of transition. Italian immigration had ceased in the mid-1920s and the community instead focused on assimilation and becoming American. Father Andolfi led the expansion of the parish into the Pleasant Valley section of Methuen, which was largely Italian, with the founding of St. Lucy's in 1960. Parishioners by this time actively participated in all aspects of the church, making the Holy Rosary and its schools one of the strongest in Lawrence. Its St. Rita's Soldality, founded by Father Milanese, remains one of the strongest female lay organizations in all of the Merrimack Valley. See https://www.saintritasodality.com/ Below: Father Andolfi's Golden Jubilee (50th Anniversary of being a priest), April 30, 1961. Below: The current state of Holy Rosary school, Lawrence, Mass. It has been closed since 1994. (Source: Queen City blog of the archivist of the Lawrence Public Library)

3 Comments

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed