|

Everyone in the Greater Lawrence area seems to know the story of the Bread and Roses Strike of 1912. It stands out for two reasons:

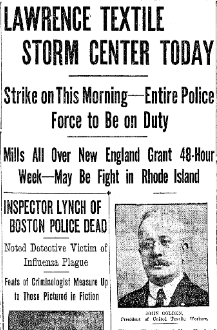

Below: Lawrence strike announced in the New York Times, February 3, 1919 How things had changed between 1912 and 1919 Even though the 1919 strike occurred only seven years after the 1912 strike, the world had changed in ways that made a successful strike of this kind more difficult.

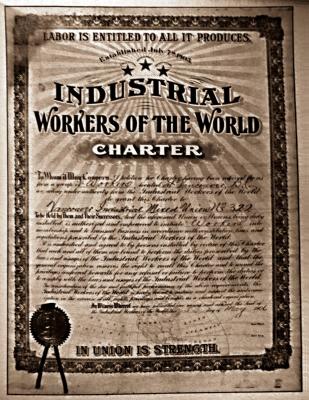

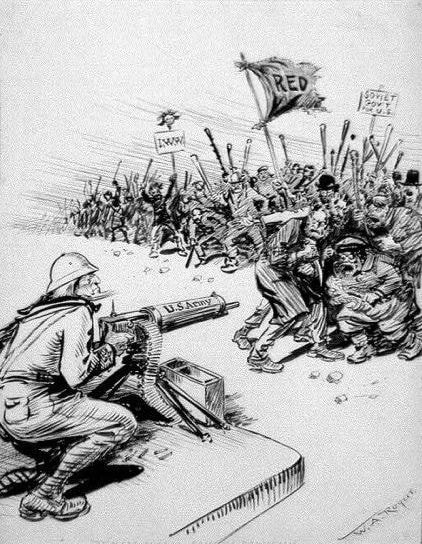

Below: The I.W.W. Charter, which reads in part "The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of the working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life." The Empire Strikes Back: The Red Scare and the Anti-Immigrant Political Climate H.L. Mencken summarized the political climate of 1919 in his book The American Scene. It was in sharp contrast to the climate in 1912, when unfettered immigration was widely tolerated because it fed the high demand of industry for cheap labor. “Returning servicemen found it difficult to obtain jobs during this period, which coincided with the beginning of the Red Scare. The former soldiers had been uprooted from their homes and told they were engaged in a patriotic crusade. Now they came back to find ‘reds’ criticizing their country and threatening the government with violence, Negroes holding good jobs in the big cities [until this time virtually no blacks had moved to northern cities], prices terribly high, and workers who had not served in the armed forces striking for higher wages. A delegate won prolonged applause from the 1919 American Legion Convention when he denounced radical aliens, exclaiming “Now that the war is over and they are in lucrative positions while our boys haven’t a job, we’ve got to send those scamps to hell.” The major part of the mobs which invaded meeting halls of immigrant organizations and broke up radical parades, especially in the first half of 1919, was comprised on men in uniform….” “As the postwar movement for one hundred percent Americanism gathered momentum, the deportation of alien nonconformists became increasingly its most compelling objective. Asked to suggest a remedy for the nationwide upsurge in radical activity, the Mayor of Gary Indiana, replied, ‘Deportation is the answer, deportation of these leaders who talk treason in America and deportation of those who agree with them and work with them.’ ‘We must remake America,” a popular author averred, ‘We must purify the source of America’s population and keep it pure…We must insist that there shall be an American loyalty, brooking no amendment or qualification.’ As [one writer] noted, ‘In 1919, the clamor of 100 percenters for applying deportation as a purgative arose to a hysterical howl…Through repression and deportation on the one hand and speedy total assimilation on the other, 100 per centers home to eradicate discontent and purify the nation.” “The man in the best political position to take advantage of the popular feeling, however, was Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. In 1919…only Palmer had the authority, staff and money necessary to arrest and deport huge numbers of radical aliens. The most virulent phase of the movement for one hundred percent Americanism came early in 1920, when Palmer’s agents rounded up for deportation over six thousand aliens and prepared to arrest thousands more suspected of membership in radical organizations. Most of these aliens were taken without warrants, many were detained for unjustifiably long periods of time, and some suffered incredible hardships. Almost all, however, were eventually released.” Given this climate of suspicion and hostility toward recent immigrants, a strike by unskilled workers from perhaps two dozen ethnicities in Lawrence would seemed destined to fail! Below: Anti-I.W.W. propaganda showing a machine-gun wielding doughboy holding off an unruly mob of foreigners. Opportunity for the Lawrence Immigrant Workers and the Reaction of the Authorities Opportunity In late 1918, the United Textile Workers of America (an A.F.L. union that mainly represented the skilled workers such as loom fixers) negotiated a reduction in the work-week in Lawrence to 48 hours. However, the deal not to reduce pay at the same time seems only to have applied to skilled workers. “In that climate of flexibility and accommodation it seems as if the Lawrence manufacturers, and the American Woolen Company in particular, wanted to discredit the unions altogether. At the very least they seemed to have wanted the workers to absorb the cost of the slack time of postwar reconversion.” (Source: Province of Reason, by Sam Bass Warner, Jr. (1988)) In other words, the management and the skilled workers colluded to pass the slack in production onto the unskilled loom operators by cutting their hours and their pay. The workers, sensing a déjà vu of what happened in 1912, when hours also were cut along with pay, went on strike. “On 3 February 1919, between 17,000 and 30,000 immigrant workers walked out of mills throughout Lawrence and began the ‘54-48’ strike. The strikers organized themselves among …different ethnic groups, with one leader per group. In addition, the strikers invited three pastors, known collectively as the Boston Comradeship (Anthony J. Muste, Cedric Long, and Harold Rotzel) as spokespeople. Ethnic stores and businesses supported the strikers by accepting coupons in place of cash. Meanwhile, the strikers boycotted stores that did not support the strike.” (From “Lawrence Mill Workers strike against wage cuts, 1919” by Kerry Robinson 16/02/2014; appearing on the site Global Nonviolent Action Database https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/lawrence-mill-workers-strike-against-wage-cuts-1919, retrieved February 10, 2018) Like the 1912, it was a strike of immigrants, by immigrants. “The general strike committee meets every morning in a dingy hall—the home, evidently, of a Syrian religious society [presumably the Marionite church?]. Approximately forty delegates come to this hall from the various language groups. Within its four walls, incontinently displaying faded pictures illustrating the Book of Revelation, Lawrence has formed her league of nations. That Syrian religious stronghold is vibrating with a new eloquence. New emotions, some of them powerful and portentous, are coming to unheralded expression. The hostile races are now allies.” (Source: Swing, Raymond. “The Blame for Lawrence.” The Nation magazine, April 26,1919.) Reaction The strike was dismissed by the A.F.L. as an unlawful “wildcat” strike. Therefore, the very union that negotiated the reduction in hours, the United Textile Workers, did not lead the strike. The walkout was covered by the mainstream press in hysterical terms involving “reds”, “commies” and “foreign anarchists”. The smelly, funny dressing, foreign-language-speaking strikers were seen as the vanguard of wild-eyed Bolsheviks. A Committee of Public Safety was organized, headed by Peter Carr, who had been a patrolman in the 1912 strike. He said “Lawrence is a city of 100,000 population and thirty-three different nationalities, most of whom are foreign. We feel this is a fertile field for the implanting of Bolshevist propaganda, and as American citizens it is our duty to suppress it.” (Source: Warner, cited above.) In other words, the response to the strike must be quick and fierce. Below: Photo of the Machine Gun used by Lawrence police to intimidate strikers, May 5, 1919. “The city administration of Lawrence enacted an aggressive approach against the strikers. Mayor John Hurley immediately began inviting in police from other towns. In less than a week, the city banned mass gatherings, restricted news coverage of the strikers, regulated inter-city travel, and kept the mills under constant police surveillance. After several cases of police beating strikers at the picket line and pro-mill infiltrators encouraging the strikers to react violently, the Boston Comradeship decided to join the picket line. At first, the presence of the clergymen deterred violent police action, but soon the police grew more intense. In one instance, several policemen cut off Muste and Long from the picket line, trapped them in an alley, beat them both, and arrested them for inciting a riot. A judge acquitted them a week later. On 18 February, a coalition of women strikers sent an appeal to Governor [later President] Calvin Coolidge to investigate excessive police brutality. Coolidge refused to meet with the coalition and sent a letter written by his secretary in defense of the local authorities’ actions. On 21 February, when a group of about 3000 strikers met in an open area near a garbage dump, two squads of police beat and then arrested strikers and injured several unaffiliated bystanders. The district court judge sided with the police and placed heavy fines on those arrested. After a lull in police violence, hostilities escalated again when the city received a machine gun from an unnamed source on 5 May to use against strikers. The machine gun was never used, but prominently displayed in front of the picket lines for intimidation. The next day, a group of men kidnapped two immigrant strike leaders, Anthony Capraro and Nathan Kleinman and left them beaten and disheveled in [Lowell].” (Source: Robinson, cited above) Were the immigrant strikers from southern and eastern Europe Bolsheviks, or was something else going on? A contemporary commentator from April 1919 explained the real story of the poor immigrant workers from places like Italy, Poland, the Balkans and Syria. “The fact that the strikers are foreigners divided among thirty-one nationalities, that few of them speak English or are citizens, and that some are boasting that in a short time the workers will own the mills, has been used as an argument that this is an attempt on the part of Eastern Europeans to impose upon America the fallacious economics of a misguided Russia. And in the light of this argument the hostility of the community, the shocking conduct of the police, and the obstinacy of the manufacturers are being justified. But the motives of the strike are not to be so precisely named or so conveniently dismissed. Had these foreigners swarmed to America imbued with the revolutionary spirit, and intrenched themselves in an industrial city to launch an attack, this strike would be truly a breach of hospitality. But they are here because American business demanded cheap labor, and many of them were even solicited by textile agents. For years the textile manufacturers have carried on a policy of gathering in the peasants of Eastern and Southeastern Europe to operate the looms of New England. These immigrants were distributed so that no more than fifteen per cent. of any one race were employed in a single mill, and the apportionment was dispassionately determined so that men and women racially hostile to one another worked side by side. This was to render organization impossible, and thus keep wages low.” (Source: The Nation article, cited above.) In other words, these workers were induced to come here because they would provide cheap labor, and their ethnicity and foreignness was used to keep them weak. Amazingly, the American Woolen Company, the main textile manufacturing company in Lawrence, had a direct hand in inviting such workers that they now faced at the picket line. “The American Woolen Company, which owns four of the eight Lawrence mills, posted lithographs throughout the Balkans depicting one of their factories as a magnificent edifice, a veritable palace of Midas, through one portal of which an army of ragged peasants marched, only to emerge from a neighboring doorway splendidly arrayed and bearing trophies—an unparalleled vision of instantaneous American alchemy. Unfortunately, actualities and visions are not allied. In red brick factories, one prodigious tier of glazed windows upon another, the European peasant has tended the looms and the spindles, and has received at the end of the week less than a living wage. The Lawrence manufacturer has not so much as justified the first unwritten premise of his posters; he has done nothing comprehensive to make Americans of these disillusioned immigrants.” (Source: The Nation article) I would really like to get my hands on a copy of the false advertising pamphlets, presumably published in Italian, Croatian, Serbian, Polish and all manner of other languages and distributed in poor rural regions to attract workers to Lawrence, where they would be kept in ethnic ghettos unable to organize with other groups of workers. Below: Poster encouraging immigration to America aimed at Russian Jews (if I can find something more on point, I will replace it) Return of the Jedi: Victory for the Strikers The immigrant workers, many of whom had been lured to Lawrence by suggestions of a better life by the employers against whom they now struck, triumphed over the Red Scare prejudices of the day and the direct hostility of the authorities. According to Robinson, cited above: “In early April, Governor Coolidge forced state arbitration between the strikers and the mill owners. The hearings held by the State Board of Arbitration and Conciliation lasted for nearly a month, but they did not lead to a compromise. However, these hearings marked the first time since the strike began that both sides directly communicated with each other. Seeing an opportunity to share credit for the resolution of the strike, the United Textile Workers [remember them??] reappeared in mid-May and negotiated with mill owners without the knowledge of those involved in the strike. The union secured a 48-hour work week as well as a 15% wage increase, more than the 12.5% increase the strike demanded. The mill owners accepted the terms since they were in need of workers and did not wish to negotiate with the strikers. Meanwhile, the strike had run out of funding. After weeks without monetary relief for strikers, organizers were ready to announce the strike as a failure. On 19 May, just as Muste prepared to announce the end of the strike, the mill owners called him to the conference with the UTW and explained the new agreement. Muste and the other organizers added a non-discrimination clause allowing the strikers to claim their former jobs. The mill owners accepted the conditions, and on 20 May 1919 the strike ended.”

2 Comments

Ray Mazurek

8/5/2019 08:15:00 am

This is very interesting. I grew up in Lawrence in the 1950s and 1960s, leaving for college in 1970, and when I was a child no one in my experience knew about the Lawrence strike, it seems, although one history teacher at Central Catholic alluded to it. My grandfather, it turns out, was in the original 1912 strike.

Reply

Carl McCarthy

8/5/2019 01:22:56 pm

Dear Professor, thanks so much for taking the time to read my blog article and comment. I just ordered the book you referred to. After I read it I’ll put it on my growing shelf of Lawrence related history books. Aside from the Lawrence angle, events of 1918-1920 are fascinating to me: Red Scare, Red Summer (attacks on blacks who had moved north in World War I to fill the labor shortage), prohibition, immigration acts, etc. Nativist, small town American ascendancy for sure. Relevance to our current period perhaps? Best, Carl McCarthy

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed