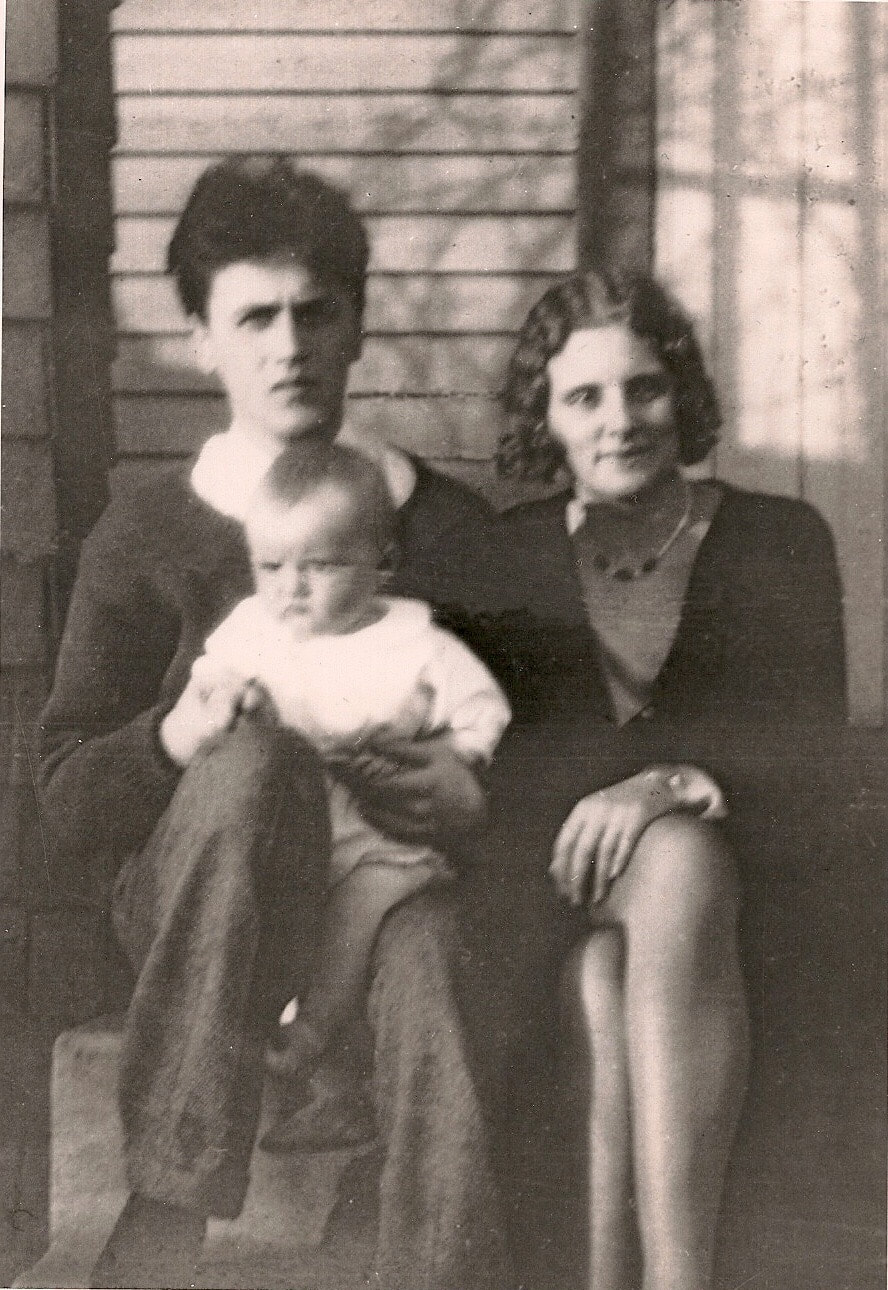

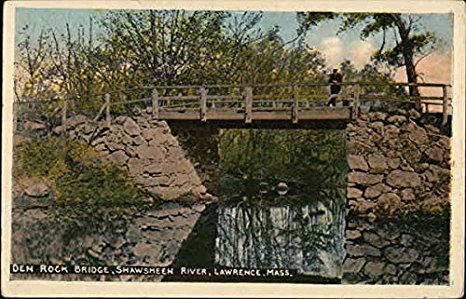

#52Ancestors challenge, week 7: My grandfather illustrates the industrial heritage of three towns2/18/2018 Below: My grandfather Clifford McCarthy, age 18, my grandmother Gladys Johnson, age 17, and my father, late autumn 1930(?). Recently, I asked my father to describe the work history of his father Clifford, who was born in Lawrence in 1912. Clifford married his high school sweetheart Gladys Johnson on his eighteenth birthday, February 3, 1930. She was four months pregnant with my father. They found a minister to do the wedding on the quick, in North Reading a few towns away. The stock market crash had been the previous October, before which Clifford's prospects seemed very different. Now, he was a married man with a family to support. Banks were failing and employers were closing. The Great Depression was descending over everything. He took his high school diploma that spring at Lawrence High and went to work. Below: The Kuhnardt Mill in Lawrence around 1930 judging by the cars in the background. This building still stands today. Source: Lawrence History Center .According to my father, "The first job of my dad’s, as I remember, from my pre-school days, was as a jig operator in the dye house at the Kuhnardt Mill by the Duck Bridge on the north side of the Merrimack River [in Lawrence]. His boss was his brother-in- law Wiliam Howarth. I heard complaints (from my mother?) that Bill picked on him." This was one of the stories of my grandfathers' employment history, working for in-laws who got him jobs. Later, he got a job with the Boston & Maine railroad through his father-in-law, who was an engineer. Years after that, in 1949, my father got a job working for his uncle Bill Howarth. It was at a dye house in Peterborough, New Hampshire. They were both working there because the mills in Lawrence were laying people off. Soon, the dye house in Peterborough also closed, and Bill Howarth moved to North Carolina to follow the textile industry south. But I digress... Because it was the Depression, there were times when my grandfather was laid off. "We received free flour from some source and my mother made "Johnny Cake” with it, which I liked," said my father. This is when New Deal programs allowed my grandfather to earn a wage. "He also worked with the WPA during the 30s. l distinctly remember a WPA arm band. I think he was involved with building side-walks, pick-and-shovel work." My father thinks he was part of the team of WPA workers that built Den Rock Park in Lawrence. Below: A bridge in Den Rock Park, Lawrence, Mass., that was likely built by WPA workers in the 1930s. The park sits at the intersection of Lawrence, Andover and North Andover My grandfather's next two factory jobs were in Andover, where by happenstance my father also was born a few years previous. "Thereafter as I remember it both parents worked a spell at the Shawsheen Mill (American Woolen Company). If this were so, my brother and I would have been living with my grandparents at 34 South. St. [Lawrence, on the Andover town line]." Below: The Shawsheen Mills in Andover in 1977, right before they were turned into apartments. Source: Andover Historical Society "I’m pretty sure the next job my father had, during World War 2, was at the Tyer Rubber Company, on Railroad St. (where Whole Foods is now). I think he was a warehouse man. As I remember he did bring home pairs of rubbers and overshoes at times. I was then in grammar school" The Tyer Rubber factory eventually was owned by Converse. Soles for their famous Chuck Taylor sneakers were apparently produced there, along with NHL hockey pucks. Manufacturing ceased there in 1977, and by 1990 the facility had been converted into apartments. As of late, there is even a Whole Foods in the front part of the facility, showing how far the town of Andover in particular has come from its quasi-industrial past! Below: My grandfather's eminently respectable parents on the occasion of their fiftieth wedding anniversary in North Andover, Mass., 1954 "The next job I believe dad had was with the B&M Railroad. I believe Grandpa Johnson, a mechanic with the B&M at the South Lawrence round house got him the job. The job was as a mechanic assistant at the round house in Boston. So this entailed a daily round trip by train. He worked there until he got laid off when the job of assistant mechanic was eliminated altogether, this was probably when Diesel engines replaced steam engines and assistant mechanics were no longer needed. I also remember him not showing on time for supper a number of nights. This occurred when he fell asleep on the train and woke up at the last stop in Haverhill. Then he would have to take the train back to Lawrence which probably got him back home about an hour after his due time." Below: My grandfather posing with other relatives in front of one of the Johnson family cottages at Hampton Beach, New Hampshire in the mid- to late- 1940s. He is lying down in front. His final job was in North Andover, at the huge Western Electric factory that was built there after World War II. "Next he worked at the Western Electric Plant in North Andover until retirement. I’m not certain what kind of work he did there, now it comes to me, I think he was a clerk in a tool crib, if you know what I mean. In any case he liked the work as I recall." "There is one more job he had," my father added. "This was as a janitor in the building [in Andover] where Phillips Academy’s school course books were sold. Now I don’t remember if he held this job before he went to work for Western Electric or after he retired. In any case I believe he worked his butt off there. It was the only time lever heard him complain about his work. He was not there for long, as I remember." Below: Osgood Landing, North Andover (largely vacant). Formerly the Western Electric Merrimack Valley Works, then an Alcatel plant. Eagle-Tribune photo. I've been told I can work like a dog, uncomplainingly. Maybe I got it from my grandfather. Even though my grandfather was a "working stiff" (as my father calls him), he regularly wore a jacket and tie when he wasn't at work. I don't know if this was a generational thing, or whether he did it consciously in an attempt to maintain some dignity despite his fairly plebeian economic status. He liked to sketch figures, including nudes copied from Playboy (an excuse to buy the magazines despite the certain protests of my fairly prim and proper grandmother). He exhibited a lot of [unmet] artistic talent that I also seem to have inherited, which is also basically unmet. Except I at least got the luxury of drawing real life nudes, when I was in the eleventh grade at Phillips Academy. Another general point: My grandfather's work history - spanning employers in Lawrence, Andover and North Andover - illustrates the free flow of people throughout an economically integrated area. One of the themes of my blog is the formerly integrated nature of "Greater Lawrence" (meaning Lawrence, Methuen, Andover, North Andover and Salem N.H.). The separate "ghetto" status of Lawrence is only a thing of the last thirty years. My father's family lived all over the Greater Lawrence area. It all seems like it was, back in the day, one big integrated area, even into the late 1970s and in my own early memory.

0 Comments

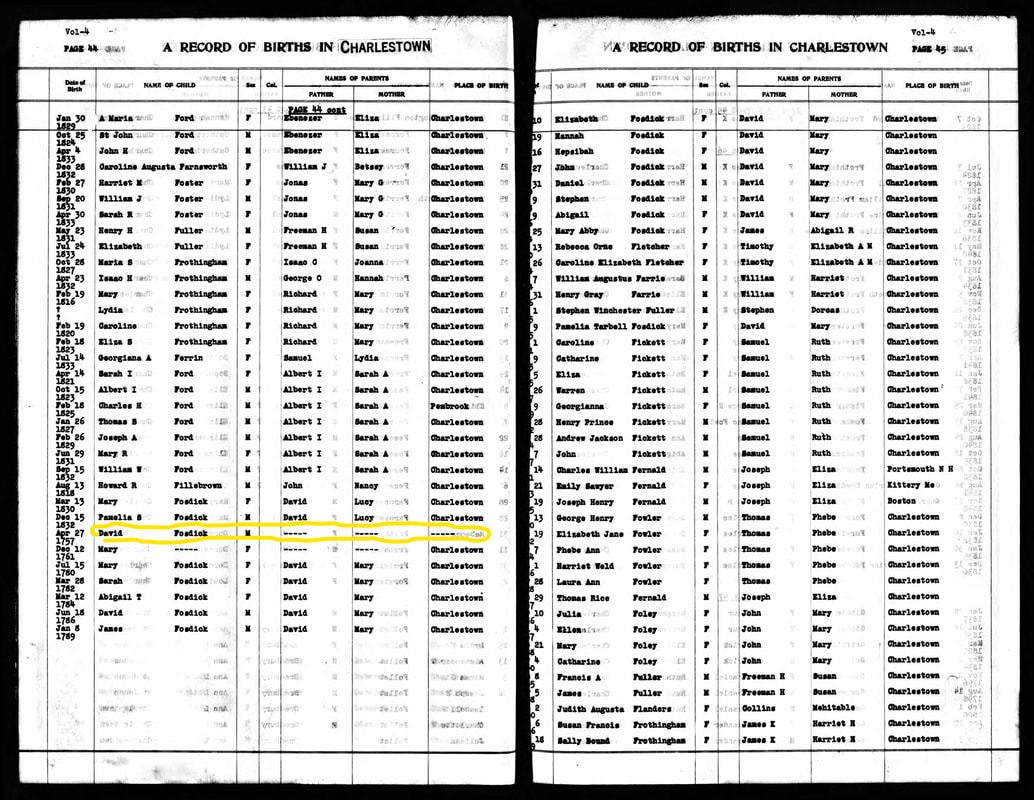

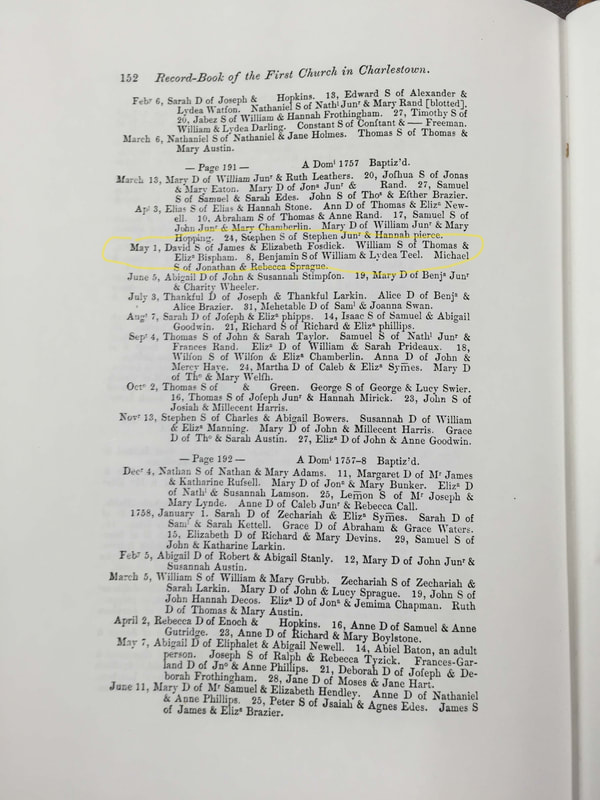

My genealogical line from William Brewster, spiritual leader of the Pilgrims, down to Edwin Ayer my great great grandfather, is as follows: Jonathan Brewster (1593 - 1659) son of William Brewster Ruth Brewster (1631 - 1677) daughter of Jonathan Brewster Mercy Pickett (1650 – d. New London, 1725) daughter of Ruth Brewster Samuel Fosdick (b. New London, 1684 – 1753 d. Charlestown)(buried Phipps cemetery) son of Mercy Pickett James Fosdick (b.1716 New London – d. 1784 Charlestown) (buried Phipps cemetery) son of Samuel Fosdick David Fosdick (b. 1757 Charlestown – d. 1812 Charlestown) (buried Phipps cemetery) son of James Fosdick Elizabeth Fosdick (b. 1791 Charlestown – d. 1855 Charlestown) daughter of David Fosdick Edwin Ayer (b. 1827 Charlestown – d. 1908 Lawrence). That's a lot of Fosdicks! What can I say about this clan (which, by the way, undermines my narrative that my ancestors arrived at the mouth of the Merrimack River and basically moved only 20 miles up river and then all stayed)? First point, the Fosdicks came to Charlestown, just north of Boston, and stayed there forever. So it's still North of Boston, meaning my basic claim holds up, that almost every American-born person from whom I'm descended was born North of Boston. I know of no ancestors born south of Boston except for the Fosdicks listed above, who moved to New London for just a few generations... probably to get away from insufferable puritans who ran Boston back then. They eventually moved back to Charlestown, however. So in my book, it's no harm, no foul! (Mr. Ayer above was of a Haverhill family; his father moved to Charlestown but he eventually moved back to Haverhill and married my great great grandmother Mary Jane Valpey of Andover, so I count him as being from the Merrimack Valley.) A couple of the Fosdicks in this list appear to have been n'er-do-wells. Stephen Fosdick (1583-1664), grandfather of Samuel Fosdick listed above, of Charlestown, Mass. was excommunicated from the puritan church for a period of twenty years, for crimes unspecified. How he got back into the good graces of the Elect is also not specified. His son John Fosdick (1626-1716) was charged with fornication by the Massachusetts authorities. “On 16 March 1649, John Fosdick, the constable of Charlestown was required (too was Ann the wife of Henry Branson) to appear at the next Court at Cambridge to answer for fornication committed by her with John Fosdick before she was married.” Despite this charge, he was allowed to remain constable, and served as a sergeant during King Philips War against the Indians in the 1670s. Another interesting thing is that, when I worked as a Park Ranger at Bunker Hill Monument in Charlestown, and lived in the Charlestown Navy Yard, I would walk to work past the Phipps Cemetery where all these Fosdicks are buried. Of course at the time, in 1994, I had no idea they were my ancestors! Anyway, my main challenge in proving lineage to William Brewster was that David Fosdick’s parent’s names were obliterated from the town birth records after the fact. Below: David Fosdick's entry in the birth records of Charlestown (circled in yellow). What happened that would cause the names of his parents (along with those of his wife's) to be obliterated from the town records?? One theory is that David Fosdick lost the family fortune - there were tales of a family "mansion" on the Charlestown neck, and hundreds of acres of land that were lost. How this happened, we don't know. Speculation in risky South Sea ventures? Ill-fated purchases of timberland in the wilds of northern Maine that got taken by the French? Investment in a merchant ship that didn't return from the Spice Islands? Anyway, I eventually surmounted this obstacle by obtaining the baptismal records for David Fosdick from the First (Congregational) Church of Charlestown. This involved my first physical research trip to conduct genealogical research, instead of just doing it online. At the magnificent facilities of the New England Historic Genealogical Society in Back Bay, I got my hands on a copy of these records. This was enough proof to satisfy the genealogist of the Mayflower Society that David Fosdick was indeed the son of James Fosdick listed above. Below: Baptismal records for David Fosdick, with a date corresponding to his birth date, and showing who his parents were. Thank god for my research that they weren't excommunicated at the time their son was born or this record would not exist. As a result of finding this evidence, my last document, the Mayflower Society genealogist accepted my application. A few months later, I received the certificate below.

Everyone in the Greater Lawrence area seems to know the story of the Bread and Roses Strike of 1912. It stands out for two reasons:

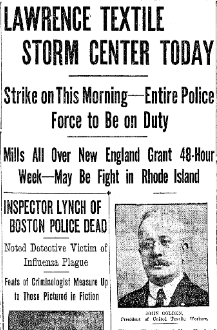

Below: Lawrence strike announced in the New York Times, February 3, 1919 How things had changed between 1912 and 1919 Even though the 1919 strike occurred only seven years after the 1912 strike, the world had changed in ways that made a successful strike of this kind more difficult.

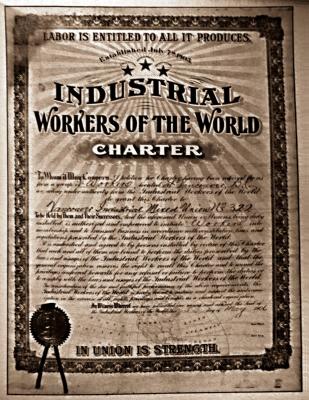

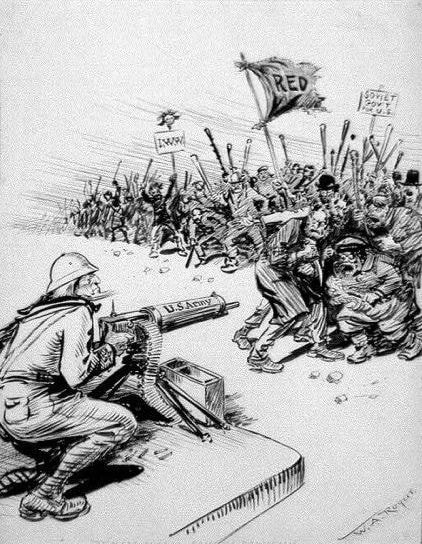

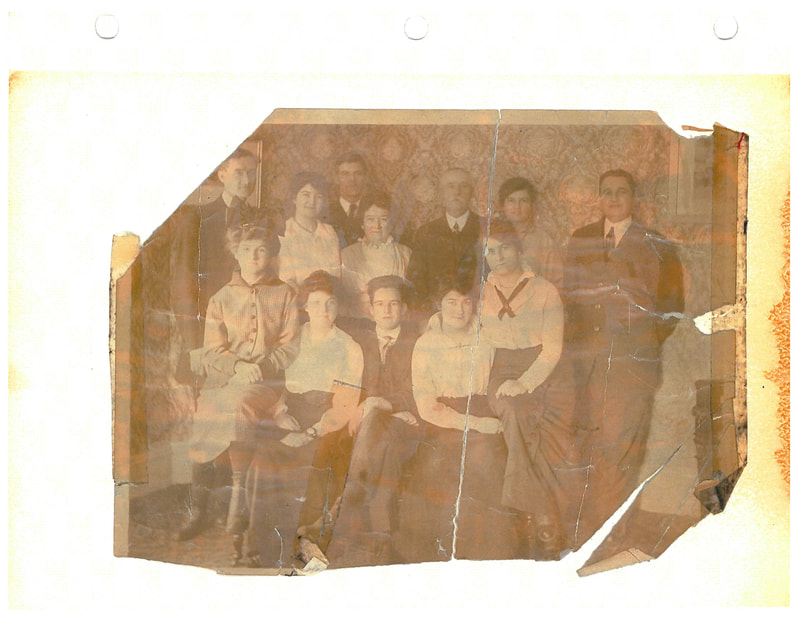

Below: The I.W.W. Charter, which reads in part "The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of the working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life." The Empire Strikes Back: The Red Scare and the Anti-Immigrant Political Climate H.L. Mencken summarized the political climate of 1919 in his book The American Scene. It was in sharp contrast to the climate in 1912, when unfettered immigration was widely tolerated because it fed the high demand of industry for cheap labor. “Returning servicemen found it difficult to obtain jobs during this period, which coincided with the beginning of the Red Scare. The former soldiers had been uprooted from their homes and told they were engaged in a patriotic crusade. Now they came back to find ‘reds’ criticizing their country and threatening the government with violence, Negroes holding good jobs in the big cities [until this time virtually no blacks had moved to northern cities], prices terribly high, and workers who had not served in the armed forces striking for higher wages. A delegate won prolonged applause from the 1919 American Legion Convention when he denounced radical aliens, exclaiming “Now that the war is over and they are in lucrative positions while our boys haven’t a job, we’ve got to send those scamps to hell.” The major part of the mobs which invaded meeting halls of immigrant organizations and broke up radical parades, especially in the first half of 1919, was comprised on men in uniform….” “As the postwar movement for one hundred percent Americanism gathered momentum, the deportation of alien nonconformists became increasingly its most compelling objective. Asked to suggest a remedy for the nationwide upsurge in radical activity, the Mayor of Gary Indiana, replied, ‘Deportation is the answer, deportation of these leaders who talk treason in America and deportation of those who agree with them and work with them.’ ‘We must remake America,” a popular author averred, ‘We must purify the source of America’s population and keep it pure…We must insist that there shall be an American loyalty, brooking no amendment or qualification.’ As [one writer] noted, ‘In 1919, the clamor of 100 percenters for applying deportation as a purgative arose to a hysterical howl…Through repression and deportation on the one hand and speedy total assimilation on the other, 100 per centers home to eradicate discontent and purify the nation.” “The man in the best political position to take advantage of the popular feeling, however, was Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. In 1919…only Palmer had the authority, staff and money necessary to arrest and deport huge numbers of radical aliens. The most virulent phase of the movement for one hundred percent Americanism came early in 1920, when Palmer’s agents rounded up for deportation over six thousand aliens and prepared to arrest thousands more suspected of membership in radical organizations. Most of these aliens were taken without warrants, many were detained for unjustifiably long periods of time, and some suffered incredible hardships. Almost all, however, were eventually released.” Given this climate of suspicion and hostility toward recent immigrants, a strike by unskilled workers from perhaps two dozen ethnicities in Lawrence would seemed destined to fail! Below: Anti-I.W.W. propaganda showing a machine-gun wielding doughboy holding off an unruly mob of foreigners. Opportunity for the Lawrence Immigrant Workers and the Reaction of the Authorities Opportunity In late 1918, the United Textile Workers of America (an A.F.L. union that mainly represented the skilled workers such as loom fixers) negotiated a reduction in the work-week in Lawrence to 48 hours. However, the deal not to reduce pay at the same time seems only to have applied to skilled workers. “In that climate of flexibility and accommodation it seems as if the Lawrence manufacturers, and the American Woolen Company in particular, wanted to discredit the unions altogether. At the very least they seemed to have wanted the workers to absorb the cost of the slack time of postwar reconversion.” (Source: Province of Reason, by Sam Bass Warner, Jr. (1988)) In other words, the management and the skilled workers colluded to pass the slack in production onto the unskilled loom operators by cutting their hours and their pay. The workers, sensing a déjà vu of what happened in 1912, when hours also were cut along with pay, went on strike. “On 3 February 1919, between 17,000 and 30,000 immigrant workers walked out of mills throughout Lawrence and began the ‘54-48’ strike. The strikers organized themselves among …different ethnic groups, with one leader per group. In addition, the strikers invited three pastors, known collectively as the Boston Comradeship (Anthony J. Muste, Cedric Long, and Harold Rotzel) as spokespeople. Ethnic stores and businesses supported the strikers by accepting coupons in place of cash. Meanwhile, the strikers boycotted stores that did not support the strike.” (From “Lawrence Mill Workers strike against wage cuts, 1919” by Kerry Robinson 16/02/2014; appearing on the site Global Nonviolent Action Database https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/lawrence-mill-workers-strike-against-wage-cuts-1919, retrieved February 10, 2018) Like the 1912, it was a strike of immigrants, by immigrants. “The general strike committee meets every morning in a dingy hall—the home, evidently, of a Syrian religious society [presumably the Marionite church?]. Approximately forty delegates come to this hall from the various language groups. Within its four walls, incontinently displaying faded pictures illustrating the Book of Revelation, Lawrence has formed her league of nations. That Syrian religious stronghold is vibrating with a new eloquence. New emotions, some of them powerful and portentous, are coming to unheralded expression. The hostile races are now allies.” (Source: Swing, Raymond. “The Blame for Lawrence.” The Nation magazine, April 26,1919.) Reaction The strike was dismissed by the A.F.L. as an unlawful “wildcat” strike. Therefore, the very union that negotiated the reduction in hours, the United Textile Workers, did not lead the strike. The walkout was covered by the mainstream press in hysterical terms involving “reds”, “commies” and “foreign anarchists”. The smelly, funny dressing, foreign-language-speaking strikers were seen as the vanguard of wild-eyed Bolsheviks. A Committee of Public Safety was organized, headed by Peter Carr, who had been a patrolman in the 1912 strike. He said “Lawrence is a city of 100,000 population and thirty-three different nationalities, most of whom are foreign. We feel this is a fertile field for the implanting of Bolshevist propaganda, and as American citizens it is our duty to suppress it.” (Source: Warner, cited above.) In other words, the response to the strike must be quick and fierce. Below: Photo of the Machine Gun used by Lawrence police to intimidate strikers, May 5, 1919. “The city administration of Lawrence enacted an aggressive approach against the strikers. Mayor John Hurley immediately began inviting in police from other towns. In less than a week, the city banned mass gatherings, restricted news coverage of the strikers, regulated inter-city travel, and kept the mills under constant police surveillance. After several cases of police beating strikers at the picket line and pro-mill infiltrators encouraging the strikers to react violently, the Boston Comradeship decided to join the picket line. At first, the presence of the clergymen deterred violent police action, but soon the police grew more intense. In one instance, several policemen cut off Muste and Long from the picket line, trapped them in an alley, beat them both, and arrested them for inciting a riot. A judge acquitted them a week later. On 18 February, a coalition of women strikers sent an appeal to Governor [later President] Calvin Coolidge to investigate excessive police brutality. Coolidge refused to meet with the coalition and sent a letter written by his secretary in defense of the local authorities’ actions. On 21 February, when a group of about 3000 strikers met in an open area near a garbage dump, two squads of police beat and then arrested strikers and injured several unaffiliated bystanders. The district court judge sided with the police and placed heavy fines on those arrested. After a lull in police violence, hostilities escalated again when the city received a machine gun from an unnamed source on 5 May to use against strikers. The machine gun was never used, but prominently displayed in front of the picket lines for intimidation. The next day, a group of men kidnapped two immigrant strike leaders, Anthony Capraro and Nathan Kleinman and left them beaten and disheveled in [Lowell].” (Source: Robinson, cited above) Were the immigrant strikers from southern and eastern Europe Bolsheviks, or was something else going on? A contemporary commentator from April 1919 explained the real story of the poor immigrant workers from places like Italy, Poland, the Balkans and Syria. “The fact that the strikers are foreigners divided among thirty-one nationalities, that few of them speak English or are citizens, and that some are boasting that in a short time the workers will own the mills, has been used as an argument that this is an attempt on the part of Eastern Europeans to impose upon America the fallacious economics of a misguided Russia. And in the light of this argument the hostility of the community, the shocking conduct of the police, and the obstinacy of the manufacturers are being justified. But the motives of the strike are not to be so precisely named or so conveniently dismissed. Had these foreigners swarmed to America imbued with the revolutionary spirit, and intrenched themselves in an industrial city to launch an attack, this strike would be truly a breach of hospitality. But they are here because American business demanded cheap labor, and many of them were even solicited by textile agents. For years the textile manufacturers have carried on a policy of gathering in the peasants of Eastern and Southeastern Europe to operate the looms of New England. These immigrants were distributed so that no more than fifteen per cent. of any one race were employed in a single mill, and the apportionment was dispassionately determined so that men and women racially hostile to one another worked side by side. This was to render organization impossible, and thus keep wages low.” (Source: The Nation article, cited above.) In other words, these workers were induced to come here because they would provide cheap labor, and their ethnicity and foreignness was used to keep them weak. Amazingly, the American Woolen Company, the main textile manufacturing company in Lawrence, had a direct hand in inviting such workers that they now faced at the picket line. “The American Woolen Company, which owns four of the eight Lawrence mills, posted lithographs throughout the Balkans depicting one of their factories as a magnificent edifice, a veritable palace of Midas, through one portal of which an army of ragged peasants marched, only to emerge from a neighboring doorway splendidly arrayed and bearing trophies—an unparalleled vision of instantaneous American alchemy. Unfortunately, actualities and visions are not allied. In red brick factories, one prodigious tier of glazed windows upon another, the European peasant has tended the looms and the spindles, and has received at the end of the week less than a living wage. The Lawrence manufacturer has not so much as justified the first unwritten premise of his posters; he has done nothing comprehensive to make Americans of these disillusioned immigrants.” (Source: The Nation article) I would really like to get my hands on a copy of the false advertising pamphlets, presumably published in Italian, Croatian, Serbian, Polish and all manner of other languages and distributed in poor rural regions to attract workers to Lawrence, where they would be kept in ethnic ghettos unable to organize with other groups of workers. Below: Poster encouraging immigration to America aimed at Russian Jews (if I can find something more on point, I will replace it) Return of the Jedi: Victory for the Strikers The immigrant workers, many of whom had been lured to Lawrence by suggestions of a better life by the employers against whom they now struck, triumphed over the Red Scare prejudices of the day and the direct hostility of the authorities. According to Robinson, cited above: “In early April, Governor Coolidge forced state arbitration between the strikers and the mill owners. The hearings held by the State Board of Arbitration and Conciliation lasted for nearly a month, but they did not lead to a compromise. However, these hearings marked the first time since the strike began that both sides directly communicated with each other. Seeing an opportunity to share credit for the resolution of the strike, the United Textile Workers [remember them??] reappeared in mid-May and negotiated with mill owners without the knowledge of those involved in the strike. The union secured a 48-hour work week as well as a 15% wage increase, more than the 12.5% increase the strike demanded. The mill owners accepted the terms since they were in need of workers and did not wish to negotiate with the strikers. Meanwhile, the strike had run out of funding. After weeks without monetary relief for strikers, organizers were ready to announce the strike as a failure. On 19 May, just as Muste prepared to announce the end of the strike, the mill owners called him to the conference with the UTW and explained the new agreement. Muste and the other organizers added a non-discrimination clause allowing the strikers to claim their former jobs. The mill owners accepted the conditions, and on 20 May 1919 the strike ended.” Above: My great grandparents Michael McDonnell and Theresa Doherty McDonnell and some of their children (with spouses), including my grandfather Joseph McDonnell standing next to and behind his mother. Michael owned a meat market and Theresa ran a boarding house across from the Arlington Mill. Michael was born in Lawrence in 1851 on Elm Street, his parents later ran a boardinghouse up Broadway just over the town line in Methuen. My grandfather was born in 1889 at a house on Broadway that straddled the Spicket River, where the little bridge is. Theresa was born in Manchester England where her parents had gone to work in the mills. Her father brought his family over from Manchester England to Lawrence by receiving $600 for fighting in the place of two different men in the Civil War in 1863. Unfortunately he never came back from that war, rather he lived out his days as an invalid in a military hospital in Bangor Maine. I think this picture was taken around 1920.

Below: The bridge where my grandfather's birthplace, 541 Broadway, used to be. Photos by me, 2016. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed