|

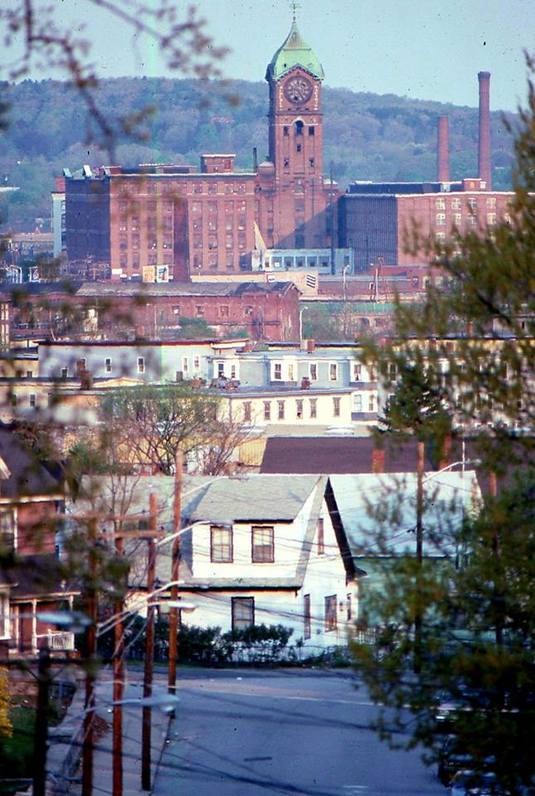

The Ayer Mill Clock Tower hovers above Lawrence, mid 1980s. Photo by Butch Fontaine.

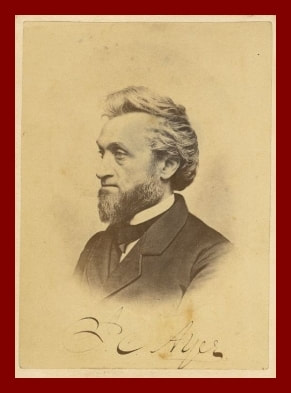

The Ayer Mill Clock Tower as a landmark There aren’t many landmarks left for a Lawrencian to point to. The beautiful post office? Demolished. The grand old police station? Demolished. “Theater Row” where many mill workers and their children watched the latest Hollywood talkies? Gone. Department store Sutherlands and the other large retail establishments of Essex Street? Gone. Also gone are many nice churches and schools, and even whole neighborhoods demolished for “urban renewal”. Most of the surviving Lawrence landmarks are industrial: the Great Stone Dam that made the whole place possible; and the mills lining the river and canals – the Pacific, the Wood, the Everett, etc. About half of the old mill buildings have been demolished. By far the most prominent landmark left in Lawrence is the clock tower of the Ayer Mill, now a New Balance factory. The tower rises 276 feet and is visible from many parts of the city, as well as from Interstate 495 passing by on the elevated roadway. It is the biggest mill clock tower in the world. As we all know, its clock face is only six inches smaller than the one on Big Ben. After decades of neglect the clocktower was restored in 1991 and has been maintained ever since. Below: Video of New Balance factory in Lawrence, Mass. This blog post tells the fascinating life story of its namesake, Frederick Ayer, peddler of patent medicines and almanacs who diversified into textiles. After you read it, maybe you’ll start calling the Ayer Mill clock tower “Big Fred”. Frederick’s background Practically every person in this country with the last name of Ayer – including my great grandmother Mildred Ayer – is descended from the original American Ayer [or Ayre or Ayres], named John. He was born in 1582 in Salisbury England and was a founder of Haverhill, where he died in 1657. John Ayer was Frederick Ayer’s fourth great grandfather, making Frederick a Haverhillite of sorts (and my sixth cousin five times removed). However, three generations earlier his family had moved from Haverhill to the coast of Connecticut. Frederick was born in Ledyard Connecticut, near New London, in 1822. Below: Frederick Ayer late in life. Source: Wikipedia His Brother James Cook Ayer and Ayer’s Patent Medicines For the early part of his life, Frederick followed in the shadow of his older brother, “Dr.” James Cook Ayer, born 1819. James studied medicine, apparently in Philadelphia, and may or may not have become a proper doctor. He did however become an extremely successful proprietor of patent medicines. James started practicing as a pharmacist in Lowell in 1841 at age twenty-three. His uncle lent him the money to buy his original pharmacy in Lowell. He settled there because his mother, a Cook, was from the Lowell area. He was a graduate of Westford Academy in neighboring Westford, Mass. Below: "Dr." James Cook Ayer, from his 1874 congressional campaign While a pharmacist James began developing cures for his customers’ ailments, and soon founded J.C. Ayer & Company. His five major products were Cherry Pectoral (“cure-all”), Cathartic Pills (laxative), Sarsaparilla (cure for syphilis and other “blood disorders”), Ague Cure (anti-malaria), and Hair Vigor (against thinning hair). Cherry Pectoral was by far his most popular and profitable product. Its popularity was possibly aided by three grams of opium in every bottle. In 1859, the company built a facility at 165 Market Street, Lowell, which they later expanded. By 1865, Ayer employed 150 people. In one year the factory processed 325,000 pounds of drugs, 220,000 gallons of spirits and 400,000 pounds of sugar. Below: Ayer's Cathartic Pills. Source: Cliff Hoyt website (http://cliffhoyt.com/jcayer.htm) Ayer’s Almanac James distinguished himself from other quacks – um, I mean doctors – by means of extensive advertising. In 1851, he hit upon the idea of providing a free almanac to all his customers. Almanacs were already essential household items, offering a range of helpful information for the current year – from public holidays to suggested planting times to town directories to historical summaries. However, James also peppered his almanac with advertisements for his products. Print production of Ayer’s Almanac is estimated to have exceeded 16,000,000 and was possibly as high as 25,000,000. The J.C. Ayer Company’s modest slogan for its publication was ‘Second only to the bible in circulation.' The almanac was eventually published in twenty-one different languages, reflecting the burgeoning immigrant population of the last decades of the nineteenth century. Below: Examples of foreign language copies of Ayer's Almanac (Source: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/almanac/heyday.html) James looked for a marketing opportunity wherever he could find it. For example, during the Civil War when Congress allowed postage stamps to become legal tender due to a shortage of currency, James encased stamps in miniature advertisements to protect them from wear and tear but also market his brand (source: www.cliffhoyt.com/encased_postage.htm). Below: Encased postage stamps bearing J.C. Ayer insignia (Source: Cliff Hoyt website http://cliffhoyt.com/encased_postage.htm)

Above: Advertisement for Ayer's Sarsparilla. Source: NIH website

Transition of The Medicine Business to Frederick; James’ Business and Political Pursuits; His Untimely Death In 1855, James offered his brother Frederick a partnership, and ceded day-to-day operations to his younger sibling. He started to become a man of wealth and leisure, traveling on extensive tours. In 1865, he purchased a statute on a trip to Germany and presented to the City of Lowell. This “Winged Victory” statue still stands today in Monument Square in front of Lowell City Hall. Below: Victory Statue, Monument Square, Lowell (Source: Wikipedia) By the 1850s, he was looking for investments for his enormous profits. However, he seems to have been the “dumb money” that came in late – in 1857, he lost $2 million dollars when the Bay State mills in newly founded Lawrence went bankrupt. That was an enormous sum of money in those days. Later, in his book Some of the Uses and Abuses in the Management of Our Manufacturing Corporations, he complained of the ways in which shareholders like him were denied a voice because entrenched management controlled the governance apparatus of corporations. Basically, he said, the insiders rigged shareholder elections. These days, someone like James C. Ayer is called an activist shareholder. In the book James launched an attack on the firm of A. & A. Lawrence, the powerful firm founded by brothers Abbot and Amos Lawrence, consummate Boston Brahmins and benefactors of great cultural institutions. (Lawrence, Mass. is named after Abbot Lawrence.) I take this as an indication that the Ayers were outsiders, not connected to the commercial elite of Boston, such as the Lawrences, with their ties to Harvard and Unitarianism (you know, “Cabots talking to Lowells and Lowells talking to God” and all that). This observation helps explain Frederick Ayer’s very unusual decision, in 1886, to allow the swarthy Portuguese immigrant’s son, William Wood (a.k.a. Guilherme Madeira), to run his textile empire and marry his daughter. More on that below.

Ayer, Massachusetts (formerly a section of Groton) was set off and named after James Ayer in 1871 when he paid for the new town’s city hall. He had dreams of becoming an important public figure. In 1874, he ran for Congress and was heavily defeated. He was so unpopular, the citizens of Ayer even burned him in effigy. This was apparently too much for his ego to handle. He went mad, spending a number of months at a private insane asylum in New Jersey. James died in 1878, leaving his brother Frederick to run the family business empire for another forty years until his death in 1918.

Below: The Town Seal of Ayer, Massachusetts, named after James Cook Ayer Frederick Ayer Takes Over In 1878, Frederick was fifty nine years old and a millionaire many times over thanks to the patent medicine business. However, by this time he had embarked on his second act: textile magnate. After a number of setbacks – and the loss of stupendous amounts of money as his family’s mills in Lawrence kept going bankrupt – he managed to get a handle on matters by hiring William Wood of Fall River to run the businesses. The relationship began in 1886 when Ayer met Wood while the latter was selling shares to a new mill he wanted to build in Fall River. Instead of investing in Wood’s mill, he hired Wood to help run Ayer’s mill in Lawrence, the Washington Mill. One thing led to another, and within a few years Wood was making $25,000 a year (up from his original pay of $204 a year) and he had married Frederick Ayer’s daughter. Below: Frederick's Son-in-Law, William Madison Wood, 1914 (Source: McClure's Magazine) As William Wood’s biographer wrote of the 1888 marriage between William Wood, age 30, and Ellen Wheaton Ayer, age 29:

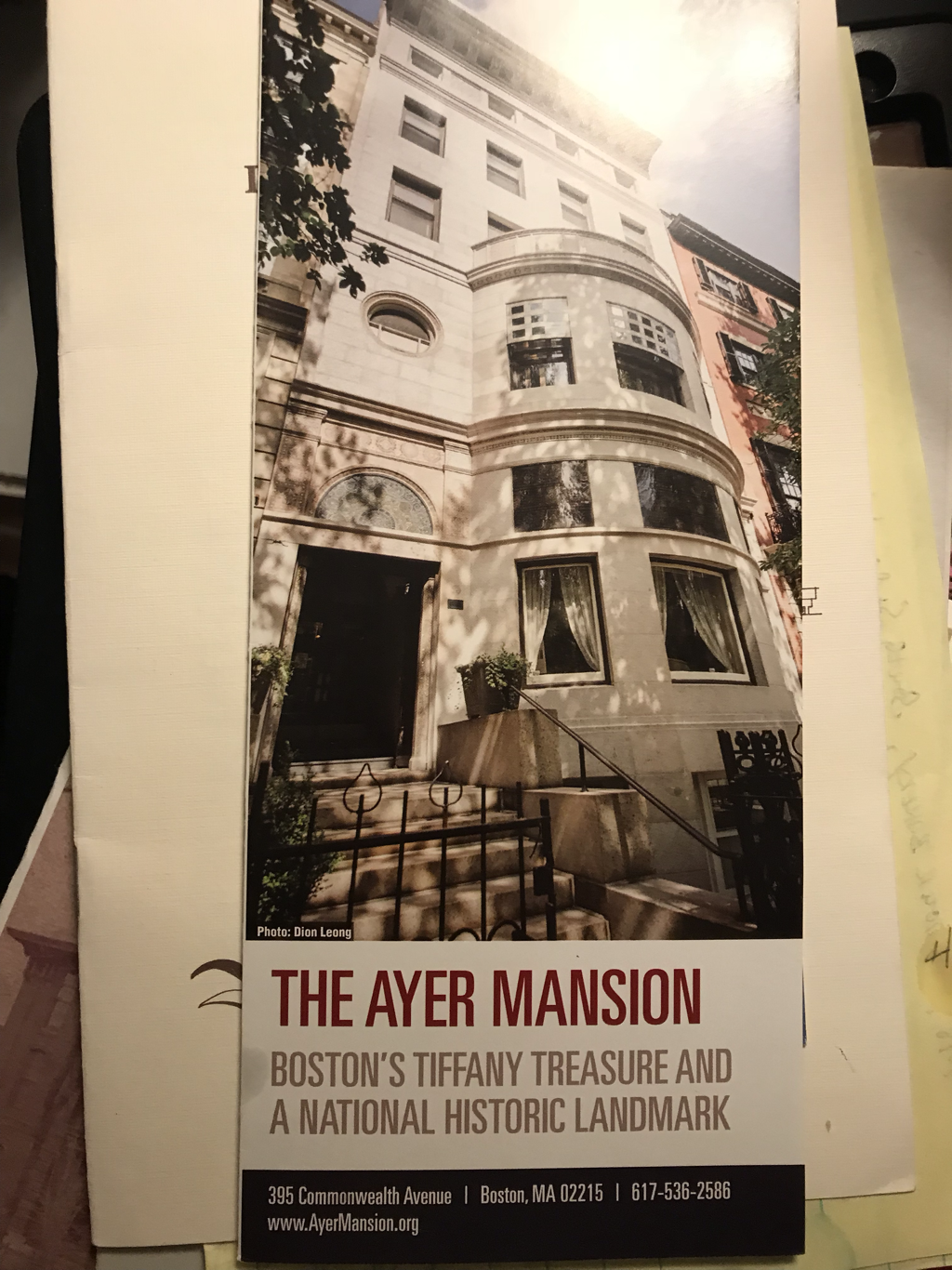

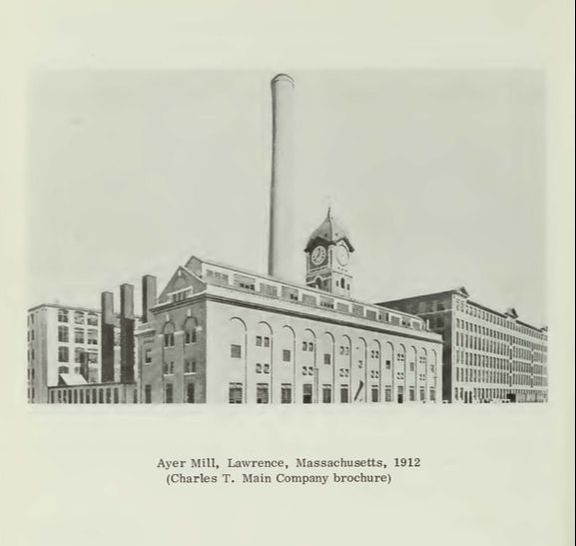

in addition to his involvement in patent medicines and textiles, Frederick Ayer was a founding director of the New England Telephone and Telegraph Company, serving in that role from 1877 to 1896. He was also a founding director of the Lowell & Andover Railroad, a subsidiary line of the Boston & Maine, serving from 1873 to the time of his death. (Source: his New York Times obituary, March 15, 1918.) Below: The Frederick Ayer Mansion, 357 Pawtucket Street, downtown Lowell (Wikipedia) Above: Brochure for the Ayer Mansion on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston Frederick Ayer was President of the American Woolen Company until June 1905, when he retired at the ripe old age of 83. Keep in mind that Ayer was still having children (with his second wife after the first one died) as late as 1890, when he was sixty eight! Frederick Ayer lived to be 95, passing away in 1918 in Thomasville, Georgia, known as “Yankee’s Paradise” for the number of northern industrialists who had winter homes there. One of James’s daughters married George Patton, the famous American commander in World War I. In 1909, William Wood honored his father-in-law by naming his most architecturally prominent mill after him. Below: Illustration of the original Ayer Mill complex from a company brochure, 1912 The Ayer Mill The following is a description of the Ayer Mill in a wonderful study of the architectural heritage of the lower Merrimack Valley by Peter Molloy (published 1978 by the sadly now defunct Merrimack Valley Textile Museum): “The Ayer Mills were designed by Charles T. Main Architects and built for the American Woolen Company as that firm's third worsted mill in the city of Lawrence. The mill was named for Frederick Ayer, a Lowell patent medicine manufacturer and the father-in-law of William Wood, the President of the American Woolen Co. The Ayer Mill manufactured worsted suitings and every operation in worsted manufacture was accomplished within its two mill buildings and dye house. An underground tunnel connected the Ayer to the Wood Mill, which was situated within 200 feet of the Ayer. During the 1950s the American Woolen Company ceased operations, and the Ayer Mill was tenanted to a number of small concerns. The dyehouse and boiler-turbine house were destroyed to create a parking lot. The boiler-turbine house contained eight 600 HP boilers and two 2. 5 MW turbo-generators. The dyehouse was 2 stories, brick, 90' x 126'. Of the two remaining mill buildings No. 1 is brick, 6 stories in height, 123' x 595'; No. 2 is 7 stories, brick, 123'x329'. The 2 mills are connected at the east end by an 8 story building, 40'x81', which contains water closets and stairways. Another building, 40'x81', connects the west ends of mills 1 and 2. This building was used as a stair and elevator tower. Above the roof level of this building rises a 40' x40' brick tower, the weather vane of which is 267' above street level. In the tower was a 20,000 gallon water cistern, a bell, and a clock with 4 illuminated dials each 22' 6" in diameter. The buildings were decorated with elaborate facades in a neo-Georgian style, with pediments, granite coursings, and Palladian windows. The buildings are among the most highly styled 20th century mills in the United States. In 1910, the mill's first year of operation, it contained 75 worsted cards, 80 combs, 45,000 spindles, and 320 broadlooms. It employed over 1,000 workers. Although situated near the Essex Company's South Canal, the Ayer did not utilize water turbines, but it did use water from the canal for process and boiler water.” Below: Frederick Ayer grave, Lowell, Mass. (Source: Find A Grave)(Note the famous "Ayer Lion" in the Lowell Cemetery is James's grave)

11 Comments

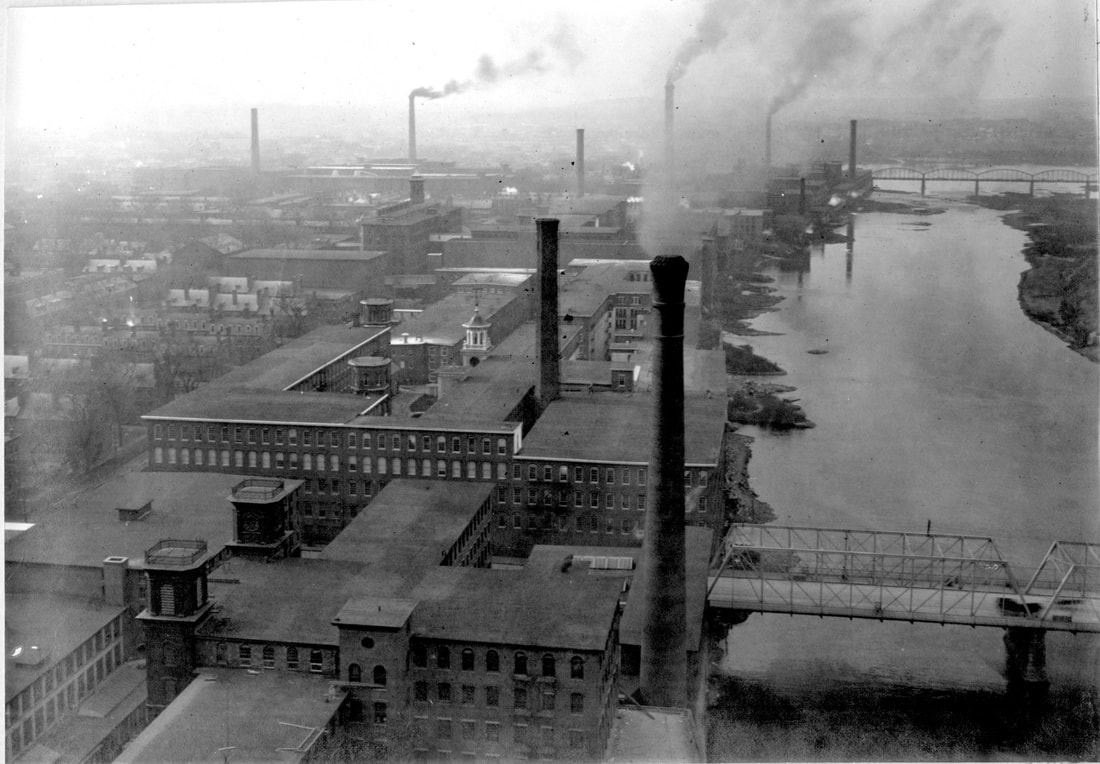

Above: Lowell in its manufacturing heyday. Source: UMass Lowell Introduction: Lowell before the French Everyone knows the story of Lowell's original workers, Yankee-farm girls who worked in the textile mills to earn a little money before returning to rural farms to get married. Introduced in 1826 upon the founding of Lowell, this system of labor collapsed when destitute Irish immigrants poured into the area following the Potato Famine. These poor Irish provided cheaper labor under worse conditions than the mill girls could ever tolerate. A few decades after their arrival in Lowell and other cities, the Irish had established a foothold, basically creating the Catholic Church in New England along the way. They also began to participate successfully in local politics. By 1882, Lowell had an Irish-American mayor. In the Merrimack Valley and elsewhere, later generations of immigrants, usually Roman Catholic, had to contend with Irish dominance of key institutions in the Church and the local government. This will be covered in other blog posts. The first immigrant group after the Irish in the Merrimack Valley were the French-Canadians. They are also the only immigrant group to arrive by train. French-Canadian Immigration French Canadian immigrants had been crossing the border into the United States since the 1840s, searching for better farming conditions and settling along the northern reaches of New York State, Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine, where in some towns they comprised the majority of the population by the time of the Civil War. However, after the Civil War, migration patterns focused on New England's growing manufacturing centers. French-Canadians ultimately were concentrated in Fall River, Lowell, Manchester (N.H.), Woonsocket (R.I.), New Bedford, Holyoke, Worcester, Lewiston (Me.), Biddeford (Me.) and a few lesser manufacturing towns. (Source: The French Canadians in New England, by William MacDonald, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 12, No. 3 (Apr., 1898), pp. 245-279, Oxford University Press.) Lowell had a total population of approximately 41,000 in 1870, of which 3,000 were French-Canadian, compared to around 20,000 Irish. By 1881, there were approximately 10,000 French Canadians, showing the tremendous rate of immigration. By 1909, the number of French Canadians had nearly caught up to the number of Irish (including in both cases children of immigrants): 20,000 versus 22,300. (Source: The Record of a City: A Social Survey of Lowell, Massachusetts, George Frederick Kenngott, Macmillan Company, 1912) In Lowell, like elsewhere, French Canadian immigrants adhered to the ethos of la survivance:

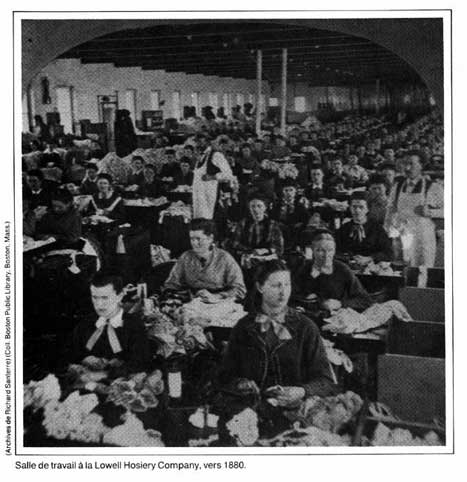

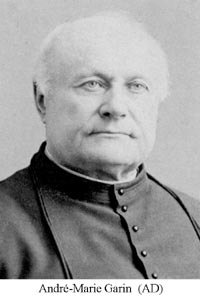

(From French Canadians in Massachusetts Politics, 1885-1915: Ethnicity and Political Pragmatism by Ronald Arthur Petrin, Balch Institute Press, 1990) La Surivance led the French-Canadians to insist upon their own institutions, and it ended up being the Oblates (and a number of other French-speaking religious orders such as the Grey Sisters of Ottawa) who provided them. Below: French-Canadian women at work in a Lowell hosiery factory, 1880.  Left : The heart of Little Canada, Hall & Aiken Streets, Lowell, 1923. Source: Lowell Sun The "Little Canada" of Lowell was pretty much one of these "dismal proletarian districts". It was situated along the Merrimack River in central Lowell, behind the textile mills around Aiken, Austin, Cheever, Hall, Tucker, Ward, Ford, Decatur, Race, Merrimack and Moody Streets. Below: The memorial plaque for Little Canada (Le Petit Canada), the core French-Canadian neighborhood of Lowell, Aiken Street. The neighborhood was demolished for urban renewal in 1964. It was into this area (and nearby French-Canadian neighborhoods) that the Oblates came in 1868, to serve the religious and cultural needs of the burgeoning French-Canadian population of Lowell. The Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate The Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate (OMI) was founded in 1816 by Saint Eugene de Mazenod, a French priest born in Aix-en-Provence in the south of France. In 1841, Canada became their first foreign mission. With steady reinforcement from France and Canadian recruits, they moved up the Ottawa Valley, and in 1845 into the North-West, where the establishment of the Catholic Church in western Canada was largely Oblate work. Coming to the United States and Lowell By 1853, the Oblates were following the French speaking population into the United States, setting up a mission in Plattsburg, New York, followed by one in Buffalo, New York. By 1857, they oversaw St. Joseph's in Burlington, Vermont. In December 1867, Father Florent Vandenberghe, provincial superior of the Oblates, based in Montreal, met Archbishop John J. Williams of the Archdiocese of Boston while attending the dedication of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Burlington, Vermont. Arrangements were made for two Oblate priests to be sent to Lowell at the invitation of the Archdiocese, to minister to the growing French Canadian population. Below: Father Florent Vandenberghe of Montreal, Provincial Superior of The Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, who directed two Oblate priests to Lowell in 1868 Founding of St. Joseph's and Immaculate Conception churches (both still active today) Following their conversation in Burlington, Archbishop Williams had been active, and found a former Unitarian Church on Lee Street, Lowell, for which he entered negotiations, hoping it would be the future site of the Oblates' parish. In March, when weather conditions improved, Father Vandenberghe traveled with Bishop Williams to view the site, but expressed some concern about the ability of the small French Canadian population there to sustain a parish of its own. This prompted Bishop Williams to propose that the Oblates establish two parishes, the second an English-speaking parish, to which Father Vandenberghe agreed. Father Vandenberghe sent two priests, Fathers Andre Garin and Father Lucien Lagier, who arrived in Lowell on April 18, 1868. Within a few short weeks, the Canadian Catholics contributed enough money for a down payment on the Lee Street Church, and dedicated it to St. Joseph on May 3, 1868, the city's first French-speaking parish. The second parish agreed to was temporarily located at St. John Chapel, initially part of St. John Hospital (then at the corner of Fayette and Stackpole Streets and now part of "the Saints" campus of Lowell General Hospital), and dedicated to the Immaculate Conception. (Source: Oblates Come to Lowell to Serve French Canadian Catholics, by Thomas Lester, Friday, January 19, 2018 https://www.thebostonpilot.com/opinion/article.asp?ID=181298) Below: Immaculate Conception, East Merrimack Street, Lowell (rebuilt after fire 1912-1916). Source: Wikipedia Despite the successful foundation of two churches, it was soon determined that the heart of the neighborhood lacked a church. The aforementioned Father Garin made it his life's work to establish a church there, dedicated to St. Jean Baptiste. Below: Fr. Andre-Marie Garin, OMI, "L'inoubliable Fondateur" "Father Garin was a native of France, and a missionary worthy of comparison with Marquette, Breboeuf, and others whom that ever-vital nation has sent to our shores. He had traveled by canoe and snow-shoe through Labrador, and on the coast of Hudson's Bay; had lived without food for forty-eight hours on an ice-floe; and had translated books into rare Indian tongues. His vigorous presence aroused the Canadians of Lowell." (from The History of the Catholic Church in the New England States, Volume I, by Rev William Byrne et al, 1899) Like Father O'Donnell who basically founded the Augustinian presence in nearby Lawrence, Father Garin was a larger-than-life figure so needed by recent poor immigrant communities. In 1869, Father Garin performed the first French language Mass in Lawrence, where the French speaking population still only numbered in the hundreds. In due course, another French-speaking religious order, the Marists, would take over the French parishes of Lawrence. That is the subject of another blog post. In 1893, he was chosen as the delegate to the meeting of the General Chapter of the Oblates in France. Then he turned his attention to completing St. Jean Baptiste. Establishment of St. Jean Baptiste The new church was part of St. Joseph parish. "St. Joseph would be expanded several times in the following years, but never proved adequate for the burgeoning French-speaking population in the Lowell area. To solve this problem Father Garin hoped to build a new church, and in 1887 purchased land on Merrimack Street on which to do so, the eventual site of St. John the Baptist, dedicated on Dec. 13, 1896." "Sadly, Father Garin would not live to see its completion, having died the year before on Feb. 16, 1895. At the time of his arrival in 1868, there were 1,200 French-speaking Catholics in Lowell, and by the time his new church was completed, it was responsible for serving close to 20,000." (Source: Byrne history, 1899) The church was located in the heart of Little Canada and served as the focal point of the community for decades. "St. John the Baptist's church, which is now the principal French church of Lowell, being fully as large as St. Joseph's, and much more imposing, fronts on Merrimack street, somewhat west of St. Joseph's. It is a bold Romanesque structure, built of granite, the prevalent material in Lowell public buildings. A bronze statue in front immortalizes the resolute features of its founder, Father Garin." (Ibid.) As noted by Byrne in his history of the Catholic Church in New England, "The French church is popular even among the Irish-Americans of Lowell, numbers of whom attend its services. Attendance of Canadians, however, at the services in churches other than their own is rare." With the destruction of the Little Canada neighborhood in 1964, following years of population decline as post-war populations moved to the suburbs, in 1993 St. Jean Baptiste was closed by the Archdiocese. It was then resurrected as the sole Spanish-language "national parish" church in New England (see below), which was closed in 2004. The structure still stands and is being converted to an event space. Below: Recent Photo of St. Jean Baptiste, now an event space. Source: https://www.lowellshistoriccathedral.com/ Creation of a separate OMI Province in 1883 "This high esteem which the Oblates enjoyed here, and the success of their missionary tours, addressed to the needs of French and English congregations elsewhere, led to the creation, in 1883, of a separate province of the Order for the United States, with its headquarters at Lowell. In the same year a novitiate was founded in the suburb of Tewksbury." (covered below)(source: Byrne 1899 history) Establishment of Notre Dame de Lourdes in 1908 "At the dawn of the [twentieth] century, the need for a church in another section of the city became acute. Many of the Franco-Americans who lived some distance from St. Joseph’s Church were abandoning their religious practices. Despite their relative poverty, the people organized and founded Notre Dame de Lourdes parish in 1908 after restoring an abandoned Baptist temple. A new and modern church complex was constructed in 1962. For many years, while serving the community, the parish was greatly involved with ministry to the many immigrant minorities in the area. A special center reached out to the needs of the many Southeast Asians who have been migrating to Lowell since the war in Vietnam. The church was an active member of many interfaith social programs that reached out to the needy of that part of the city. (Editor’s Note: Following the reconfiguration of the Archdiocese of Boston, Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes was suppressed in 2004.)" (Source: https://francolowellma.wordpress.com/religious-orders/oblates-of-mary-immaculate/) Establishment of Ste Jeanne d’Arc Parish in 1922 "St. Jeanne d’Arc Parish was established on December 30,1922, by William Cardinal O’Connell. The Oblates of St. Joseph Parish had been ministering to the Franco-Americans on the Pawtucketville side of the Merrimack River area since 1920. A small school, built in 1910 by Father Campeau to accommodate younger children, was expanded and transformed into a school and chapel. The first Mass was celebrated there on the third Sunday of April 1921. By a decree of the General House, dated January 30, 1923, Father Léon Lamothe was appointed first Superior and the new residence was officially established. A new stone church was completed in 1929. Later, a new slanted roof was added to improve the outside lines of the structure, and the interior of the church has been completely renovated in conformity with the latest liturgical requirements. (Editor’s Note: As a result of the reconfiguration process, the Archdiocese of Boston ordered the suppression of Ste-Jean d’Arc parish in 2004. Ste-Jeanne d’Arc grammar school, administered by the sisters of Charity of Ottawa is still active and currently operates under the auspices of St. Rita’s Parish.)" (Source: https://francolowellma.wordpress.com/religious-orders/oblates-of-mary-immaculate/) The Oblates in Billerica - St. Andrews "Before Saint Andrew’s Parish was established [in North Billerica], thousands of Irish people, due to political oppression along with the great potato crop failure of the 1840’s and 1850’s, [had] made the trek to New England in order to seek jobs in the nearby Talbot and Faulkner mill complexes. They brought with them few material possessions, but they did bring with them a sound and living faith. These Billerica Catholics had to walk about five miles to the nearest Catholic church in Lowell to worship. In 1868, the remarkable Father Andre Garin of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate established a mission parish for the town of Billerica. He helped the small congregation arrange to buy the now-abandoned Universalist church. After the purchase, they moved it to Mill Street, now known as Rogers Street, and placed it under the patronage of the Apostle Saint Andrew. In the end, $4000.00 had been spent; but the people finally had their own church. For forty years, Saint Andrew’s Parish was in the care of the Oblate Fathers. They would come in from Lowell, at least once a month, to celebrate Mass and handle all pastoral matters. Some of these priests served for but a few months, while others remained for several years. In 1890, Father James Maloney, O.M.I. realized the need for enlarged facilities to accommodate the increased number of parishioners. His program of renovation and expansion was carried out with the physical as well as the financial help of the people. Through their generosity and selflessness, the dedicated people managed to complete a $6,910.44 renovation that increased the size of the church by one third. Imagine the sacrifices that were made considering that the average daily wage was about 85 cents!" From http://billericacatholic.org/?page_id=49 The Oblates in Tewksbury Above: The Former Oblate Fathers Novitiate

In 1883, the Oblates in Lowell founded a Novitiate, an institution typical of any Catholic religious order, in which Novices are trained and decide whether they are called to the order, either as priests or as lay members (monks and nuns). These days, it is a retirement home for Oblate priests from around North America. The Oblates and Spanish-speaking Catholics of Lowell, 1970-2004 When the first wave of non-English speaking Catholics arrived with the French-Canadians, these French-language Catholics were able to bring religious orders from Canada such as the Oblates and the Marists, to provide French language instruction. Subsequently, in the 1890s through the 1920s, the archdiocese allowed the formation of "national parishes" dedicated to the needs of a particular ethnic group, Italian, Polish, Portuguese and what have you, although they were typically run by diocesan priests of Irish background. After World War II, the "national parish" practice largely ended as these immigrant groups all became assimilated and many moved to suburbs, leading to the closure of ethnic parishes in inner cities. When Puerto Rican and other hispanic immigrants began arriving in the Merrimack Valley in the early 1970s, it triggered a debate within the Archdiocese: do we establish a separate Spanish-language national parish? Eventually the answer was: no. Integration was seen as more favorable --although (begrudging?) accommodations were made in allowing "basement chapels" to be formed where worship was conducted in Spanish. The sole exception to this rule was a Spanish-language parish in Lowell, Nuestra Seniora del Carmen, in the former St. Jean Baptiste church.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed