|

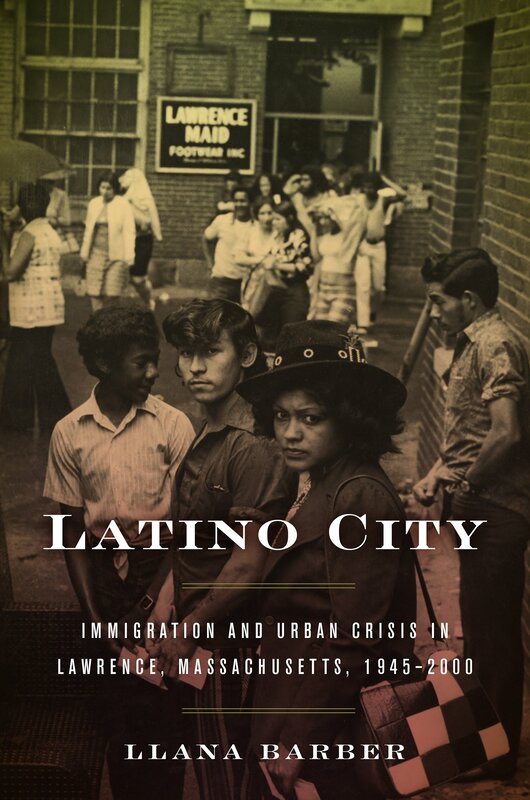

Ms. Llana Barber has written the first academic book about Lawrence's postwar transition, from declining milltown to outer-suburban Latino-majority hub. This is a very important book in understanding the recent history and potential future of Lawrence. She has all the pieces needed to tell the story:

She also has some interesting details about recent events that might interest locals. For example:

Anyone who is interested in the recent history of Lawrence, or the significance of a sizable Latino-majority city, should read this book. Background of Latino immigration and economic change She comprehensively tells the story of Puerto Rican and Dominican migration to Lawrence starting in the late 1960s. Prior to 1980 or so, most Latino immigrants were Puerto Ricans from New York who were attracted by the perceived safety of Lawrence compared to their New York City neighborhoods, plus the availability of jobs in non-durable goods manufacturing, mainly shoes – Lawrence Maid, Jo-Gal, etc. “In 1970, 83 percent of Lawrence’s employed Latinos worked in manufacturing, compared with only 34 percent in New York City,” she says. Also, Lawrence was perceived as relatively immigrant friendly in light of its history. Industrial jobs, immigrant friendly jobs and relative safeness of Lawrence compared with places like the Bronx were what started Latino immigration to Lawrence. However, by the early 1980s, industrial jobs had largely disappeared and newcomers - this time as many Dominicans as Puerto Ricans - were more attracted by the existing sizable Hispanic population. Her Analysis of the 1984 Riot I actually came across her book while checking my research on the 1984 Lawrence Riot. She has the first published analysis of the riot by an academic that I can find. (There was an unpublished Master's thesis, which is available at the Resources page.) She has an in depth description of the events of August 1984. In my view, the riot was not a very big disturbance, albeit one that local police could not get under control on the first night. It happened less than half a mile from my house with no immediate impact beyond a narrow zone running between Broadway and Margin Street along the base of Tower Hill, across an area of probably less than ten acres. I have suggested that it was more like a large-scale rumble, and not a "riot" in the same sense as the gigantic Detroit riots or Watts Riots which ranged over hundreds of acres destroying a lot of those cities. Even locally, compare the 1964 Hampton Beach riot, which involved up to 10,000 youth battling state police from New Hampshire and Maine and many neighboring towns. She has some interesting little details that I had not heard before: “At 11:00 PM rioters broke into Pettoruto’s liquor store. The Eagle-Tribune reported that at first the two groups [presumably whites and hispanics] fought over the liquor, but then they cooperated to divided it up and share it, after which a ‘lull followed with a lot of public drinking.” She notes dryly, “This odd reprieve could not have been long lived, because by 12:15 AM, the liquor store was on fire.” She also has a graphic description of police action on the second night. “At 10:30 that night, the head of the Northeast Middlesex County [i.e. Lowell area] Tactical Police Force ‘arrived to find Lawrence police pinned down – lying on the ground to avoid gunshots, rocks, bottles and Molotov cocktails.’ An early contingent of forty Lawrence police officers and the regional SWAT team had been no match for the hundreds of rioters who claimed the streets. By 12:30, however, the reinforced police from the surrounding towns and state police from six barracks, marched in cadence down the streets, pushing the Latino rioters in front of them, herding them into the Merrimack Courts (Essex Street) projects, where virtually very newspaper account assumed all the Latino rioters lived.” “Latinos lived throughout the neighborhood, however, and it is highly unlikely that all the Latinos at the riot site lived in the Essex Street projects.” She does point out that “it seems that many more white rioters were arrested than Latinos on the second night,” and that at least a handful of them were from neighboring towns who had come into Lawrence to get in on the action. She also has a very interesting reference to an editorial by Eugene Declercq in the Lawrence Eagle-Tribune (soon to be just the Eagle-Tribune, based in North Andover). “Declercq was one of very few commentators to take a metropolitan view of the riots, one that drew attention to the reality of the region's political economy. He challenged the suburban exemption from responsibility for the region’s poor, an exemption premised on politics of local control that enabled people living in the suburbs to exclude low-income residents as a way of protecting their property values and public services. ‘The cherished property values of the wealthy communities that surround Lawrence are secure because of a system that isolates its poor in cities like mine.’” He added “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free – but make sure they live in Lawrence and not near us.” Quibbles with the Book My biggest quibble is that she often falls back on a stark suburban-urban dichotomy to tell the tale of Lawrence versus its neighbors. While it is true that suburbanization (the building of federally funded highways, Freddie Mac financed suburban subdivisions and automobile infrastructure) led to the decline of Lawrence and other small cities in many ways, it does not follow that Lawrence's suburbs were somehow just Levittowns of single family homes built on farmland and shopping centers, and that Lawrence was just a teeming pit of abandoned factories and squalid tenements. As I tried to suggest in my blog entry about the separation of North Andover from Andover, there were industrialized, higher density areas of Lawrence's neighbors that blended almost seamlessly into abutting Lawrence areas. When I was a young child, my grandparents lived on Harold Street in North Andover in a duplex, on a street that almost entirely mirrored my street in Lawrence, Saunders Street, in terms of housing stock and residential demographics. And in the section of north Lawrence near where I later grew up, the neighborhood blended seamlessly into the abutting parts of Methuen. (The construction of Interstate 495 in the early-1970s probably exacerbated the distinction, as it cuts North Andover off from the Lawrence side of the former neighborhood, and provides a very clear frontier area between Lawrence and Andover). Although she tries to emphasize the urban-suburban dichotomy by regularly comparing Lawrence to Andover, this is somewhat misleading, as Andover was the most rural of Lawrence's suburbs and therefore in the best position for postwar greenfield suburban housing developments, especially because of the fortuitous location of highways and an existing commuter train station into Boston. Because of North Andover's industrial heritage, in contrast, it still had huge manufacturing employers into the 1990s. She does talk about the numerous Hispanics who lived in Lawrence and worked at Western Electric in North Andover in the 1970s and 1980s, thus undercutting her simple urban-suburban narrative. My own theory, which I suggested in my post on the August 1984 Lawrence Riot, was that the increasing dichotomy between Lawrence and its immediate neighbors was exacerbated by the 1982 desegregation of schools in Lawrence's peripheral "nice" neighborhoods. It had the effect of pushing existing residents of those neighborhoods over town lines and destroying the previous integration of those neighborhoods with the abutting neighborhoods of Lawrence's suburbs. She does describe with a lot of good detail how it is impossible to mandate desegregation or mixing of students across town lines. "Thanks to Milikken [a court case], the suburbs were not compelled to participate in any meaningful metropolitan desegregation plan, and none of Lawrence’s suburbs chose to participate voluntarily in such a plan with their nearest urban neighbor. An effort to create a voluntary ‘collaborative school’ in the late 1980s for students from Andover and Lawrence failed after it encountered intense opposition from Andover residents." The project would have been jointly run (and largely state-funded) elementary school designed to admit students from both municipalities. However, except for a passing reference to an early-eighties desegregation plan in Lawrence that "was on the verge of being implemented," she does not talk about the actually internal Lawrence desegregation process and its effects. Her analysis of the flaws of the former alderman system of government in Lawrence is well-done. This governmental structure persisted into the 1990s. "“Most critics focused on Lawrence’s alderman style of city governance. Unlike most cities, Lawrence had no professional administrators to head police, fire, street, or other departments." Its patronage based system meant an overwhelming exclusion of Latinos from city employment, although a voluntary quota system was implemented, targeting 16% in 1977 and going up from there. However, I would argue that the alderman system also had a structural benefit. It led to the existence of "crown jewel" neighborhoods in Lawrence, where most to the resources were concentrated and most of the voters lived who then benefited from patronage jobs. These neighborhoods were the upper part of Tower Hill, of Prospect Hill and Mount Vernon. Between the removal of the alderman system of government and internal desegregation, the crown jewel neighborhoods of Lawrence were basically equalized downward to the level of their poorer, less resourced neighborhoods in the flatlands. Thus, Lawrence lost a significant tax base [something that Barber continuously laments along with Lawrence's increasing dependence on state aid]. As a result of these forces, Lawrence's neighborhoods that previously could compete with similar neighborhoods in North Andover and Methuen were slowly turned into ghettos, starkly cut off from historically similar neighborhoods next door in neighboring towns. The fact that such crown jewel neighborhoods were mainly white (remember that until Hispanic migration, Lawrence was 95% white) misses the point. The point is that these neighborhoods were also of a different socioeconomic status and probably could have been a first stepping point up the socioeconomic ladder for recent Hispanic immigrants. Instead, as a result of the trends I just described, Lawrence effectively became one big self-contained Hispanic ghetto starting in the early 1990s, increasingly bifurcated from its historic neighbors. Conclusion Yet...maybe my quibbles with the emphasis of the story are wrong. Yes, Lawrence effectively became its own little Hispanic ghetto for a couple decades (I am using the term ghetto in the classic sense, as a place separated and walled off where a minority group is enclosed, such as the original ghettos for Jews in medieval Europe). However, Lawrence is arguably now turning a corner, as a completely Hispanic city. As Barber says “In a most basic sense, Latinos saved a dying city.” I agree.

0 Comments

"Kids roamed the neighborhood like dogs. The first week I was sitting in the sun on our steps, I made the mistake of watching them go by as they walked up the middle of the street, three or four boys with no shirts... the tallest one, his short hair so blond it looked white, said, 'What're you lookin' at, fuck face?'

'Nothing.' There he was on the bottom step. He pushed me hard in the chest and kicked my shin. 'You want your face rearranged, faggot?'" It is the early 1970s. A 10-year-old Andre Dubus has moved into the rough, working class part of Haverhill, known as the Avenues. He quickly sets the tone with descriptions like these of his interactions with neighborhood youth. He lives on “a narrow hill street of tin-sided houses behind chain-link fences." "Plastic children’s toys would lie on the cracked concrete among cigarette butts and empty nip bottles, and on their sides here and there would be shopping carts for when the car wouldn’t start and the welfare checks came in and usually the mothers and wives or girlfriends would push the carts a mile and a half away to DeMoulas and load up with cans of Campbell’s soup, eggs and milk, bags of potato chips and cases of Coke and Budweiser, bottles of Caldwell’s vodka. Halfway down Seventh Avenue was a cluster of yellow apartment buildings, two rows of them three-deep back from the street, each three stories high. The ground around them was packed dirt worn smooth and there was a gravel parking lot scarred from rain and in the back of it, up against a field of weeds, was a green dumpster I’d never seen empty; it was full of babies’ diapers and old mattresses." A local gang of young men run an extortion racket of sorts, "men in their twenties or thirties who earned their rent by collecting it from everyone else, two or three going from door to door on the first of the month each demanding cash. Some of them were with the motorcycle gang, the Devil's Disciples..." He becomes a fighter, a lieutenant, an instigator. What ensues is four hundred pages of violence, bravado, thuggery, petty bickering, intimidation, sadism, hooliganism. He is not an outsider, rather he is simply breathing the air around him, swimming in his ocean. Dubus becomes acculturated to violence, using the metaphor of a membrane that has to be punctured by an act of will. "This was different from sex, where if you both want it, the membranes fall away, but with violence you had to break that membrane yourself, and once you learned how to do that, it was easier to keep doing it." His summary of his school captures the prevalence of violence, even in this supposed sanctuary from the street: "The slam of a locker, the slap of feet over the hard floor, the soft thudding of a fist thrown again and again into someone's face, like waxed wings flapping, then a joyous shriek of someone yelling "Fight," and we'd all all be running to them, crowding around the two or three bodies flailing away at each other in the center. In a school of over two thousand students, this happened once or twice a week." The part of Townie that most resonated with me, in what was a hard slog through 400 pages of numbing descriptions of beat-downs and delinquency, was this: Although the story takes place in the rough part of Haverhill, it could just as well have been in almost identical neighborhoods of Lowell, or Newburyport (before it was renovated) or Lawrence. Post-industrial, worn out, working class, "inner city" (white inner city) mill town. The descriptions of the chain link fences, the dilapidated triple-deckers, sounded like, for example, the streets in Lawrence down by the Spicket River, Erving Avenue, or the lowest part of Tower Hill, along the train tracks west of Broadway. And the descriptions of the rebelliousness, the anti-authoritarian punkishness, the roughness, the chip-on-the-shoulder masculinity...I knew this from kids at the Bruce School who would "see you in the schoolyard after school" at the littlest slight, who ran in gangs, whose fathers ran in more organized gangs, like the ones that congregated the Calumet Bar and ran numbers and hookers. Luckily for me, this kind of culture was usually at the periphery growing up, down the hill, in other neighborhoods...but I knew it was there. It's full of tribalism, group loyalties and animosities, even though everyone's white and probably "white ethnic", still living the vestiges of immigrant culture three or more generations in: Irish, Italian, French Canadian, Polish, whatever. Why communities of people get like this, or why they seem to have been so prevalent in places like Lawrence and Haverhill (where in some neighborhoods disagreements were settled by rumbles)...I will leave this to the sociologists. However, I think an awareness of this culture is necessary to understand things like the Lawrence riot of August 1984. From one perspective, that riot was a big rumble, except that the counterparty, as it were, wasn't another gang of white ethnic milltown punks; it was fresh-off-the boat immigrant youth from Puerto Rico (some via NYC), and the Dominican Republic, who got provoked into engaging with this kind of local culture. This is a book that I’ve basically been looking for, for years. Although it has very interesting chapters, state by state, on the settlement of the American Midwest and West by Yankees from New England, I mainly like it for its poignant description of the depopulation of upland New England, which is relevant to my genealogical background (see “About” page of this blog).

This topic is also very poignantly covered by Robert Frost, claimed by my hometown of Lawrence because he went to high school there. See, for example, his poetry collection “North of Boston”. The dialect spoken by Frost, which can be heard on recordings of him, to me really captures the North-of-Bostonregional dialect, now nearly lost. A topic to be explored in another blog entry... Here are some good quotes from Yankee Exodus. “My interest in migration from New England began some forty years ago, when I first became conscious of the many deserted hill farms in my native Vermont, and in New Hampshire where I also lived. The old cellar holes, the orchards being slowly throttled by encroaching forest, moved me deeply. I had a fairly good idea of what had gone into the making of those hill farms and homes; and the fact that they had been abandoned, after a century or more, seemed to me a great tragedy. It still does.” “In good time I myself joined the exodus, and though I visit there almost annually, for thirty years and more I have lived outside New England. Everywhere I went, I met native Yankees or the descendants of Yankees; and came to the conclusion, in no way original, that Yankees must have had a good deal with the civilizing the United States lying west of Lake Champlain and the Berkshires; and, of more importance, had perhaps exerted an influence in those foreign parts immensely greater than was commonly believed and also all out of proportion to their numbers.” These quotes were from the book’s Foreword. The actual start of the book, chapter 1 (called “Melancholy on a Hill”) is also amazing: “The Hill, my great-grandfather had said, produces the best maple honey in Vermont and the biggest supply of material for stone fences you could imagine. He always had plenty of one, and far too much of the other. When he went there, a little after the end of the Revolution, with the truly appalling idea of clearing a farm in the forest, the entire hill was enveloped with the immense hush of an illimitable wilderness. Now, a century and a half later, the silence is returning, along wit the wilderness that is marching from the edges of the old fields and pastures straight across and up and down, swallowing miles of stone fences, tearing pastures straight across and up and down, swallowing the miles of stone fences…” The first chapter captures exactly the tenor and detail I’ve been looking for to describe life in, and then the slow depopulatingfrom, upland new England. “They all came to call on their fellow Vermonters – the Dorreliates, the Perfectionists, the Christians (from near-by Lyndon); and so, too, the Anti-masons, the antinicotine forces, the Temperance shouters; the hydro therapists, the anticalomelmen, the hosts of assorted Sabbatarians, the sellers of lightning rods. So, also, the Abolitionists, the Friends of Liberia, the vegetarians, the Grahamites, the Thomsonians, the homeopaths.” “And when the times became dreadfully hard, and Yankees in their desperation started to make gadgets and such for sale to other Yankees – because they had no other market – this house resounded to the heralds of tin calf weaners and Seth Thomas’s clocks, of mouth-organs and parent water-watches, of soapstone stoves and Thayer’s Slippery Elm Lozenges. Once, at least, came a persuasive man who sold mulberry bushes, complete with worms, on which, he vowed, any hill farmer could make a fortune from silk.” |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed