|

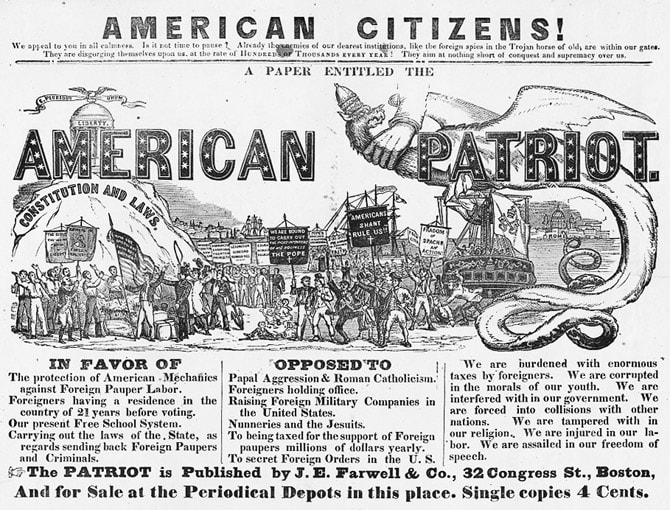

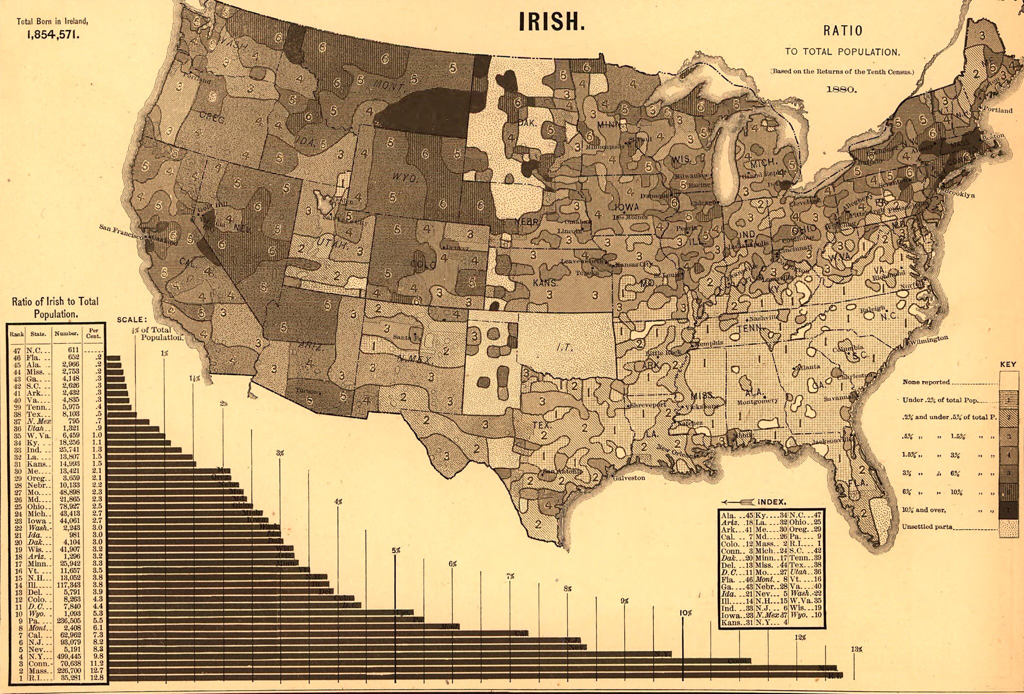

In previous blog post, I covered the Lawrence "race riot" of August 1984, which was essentially between a newcomer immigrant group, "the Hispanics", and established natives. Who says history never repeats itself? A century-and-a-quarter earlier, another riot occurred in Lawrence, between a newcomer immigrant group, "the Irish", and established natives. See news coverage above in the New York Times, July 11, 1854. The Lawrence riot of that July 11 was part of a wave of violence aimed at recent Irish immigrants. It swept New England in the summer of 1854, at the height in these parts of the Know-Nothing movement. Know-Nothing politicians stirred crowds with hysterical speeches, about how the Catholic religion was incompatible with American values. "They only answer to religious law and do whatever the Pope and the priests tell them!" "They oppress their women by putting them in convents!" These were the kinds of statements made by the Know-Nothings. It reminds me of hysterical tirades aimed at the supposed incompatibility with American values of the religion of another group of recent arrivals. Just substitute "the commands of the Pope and the priests" with references to Sharia law to see what I mean. The existence of separate religious schools run by and for Catholics particularly incensed many natives, and led to continuous political and court battles through most of the nineteenth century. The "School Question" will be the topic of another blog entry. Think about the context of this anti-Catholic animosity. I'm not defending it, but perhaps it was understandable. Your average New England Yankee had for two centuries been fed a diet of how horrible "Popery" had been, a belief borne out of Protestant experiences with the Counter-Reformation and the religious wars that plagued Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Virtually all New England churchgoers of the time would have shared a staunch belief in the supposed corruption of the Catholic Church, as was finally upended in the Reformation. This was one of the few beliefs that unified the various Protestant denominations that flourished in New England by the 1840s, Congregationalists, Unitarians, Baptists and Methodists being the main ones at this time. Furthermore, very few of these denominations had any liturgy or ritual to speak of in their worship. Also, there were vague collective memories of the French and Indian attacks, led by Jesuit warrior-priests like Father Sebastian Rale coming down from New France (i.e. Quebec) with bands of wild Abenaki Indians to slaughter English villagers. In this context then, imagine how America's first wave of Catholics, the Irish, appeared. Their worship was in a strange language, Latin. This language would have scared Yankee listeners, as it signified the supposed corrupting influences of Rome on true Christianity based solely on original biblical texts, in addition to being completely foreign. Moreover, the Catholic mass (their worship ritual) usually lacked a sermon, full of textual exegesis, which was the mainstay of Congregationalist worship; nor did it have any of the evangelical personalizing of the relationship between the individual believer and Jesus Christ, which, since the Great Awakening in the 1740s, prevailed in the non-establishment Protestant denominations such as the Baptists and later the Methodists. Instead, Catholic worship featured a man in weird robes (the priest) facing an ornate altar, making strange gestures and repeating a bunch of Latin phrases in a prescribed order, while the congregation chanted phrases in Latin in a prescribed order, kneeling, sitting and standing in turn. Imagine how frightening a group of worshipers all kneeling and bowing in unison could be! And then there was the intense scrutiny of convents and nuns, who were assumed to be under oppression and even sexual slavery, with their covered heads and existence behind closed doors. The Ursuline convent in Charlestown, Mass. was burned down by a mob in 1834 on suspicion that women were being held there against their will. And practices like praying the hours (in which devout Catholics visibly pray five times a day at prescribed hours using prescribed prayers based on a calendar), also set off suspicion and animosity, as did its simpler sister ritual, saying the rosary. Below: the cover of the American Patriot, a Boston-based Know-Nothing newspaper, 1854 In addition to the anti-Irish riot in Lawrence, many other New England towns and cities had similar riots that summer: Bath, Maine (in which a Catholic church was burned down); Ellsworth, Maine (in which a priest was tarred and feathered); Chelsea, Mass. (in which a Catholic church was attacked); Dorchester, Mass. (in which a Catholic church was destroyed by dynamite); and Norwalk, Conn. (in which St. Mary's catholic church was set on fire and its steeple sawed off), among other places. In Manchester, New Hampshire on July 4, 1854 a skirmish between some Irish youth and some "natives" over a bonfire that the former group wanted to light escalated into significant violence. The local newspaper account stated that a "large number of men, armed with clubs and other destructive implements, about day-break, commenced an assault upon all the Irish houses in that neighborhood. Some ten or fifteen were pretty thoroughly dismantled—the doors and windows of many of them being completely stove in. The rioters next proceeded to the Catholic Church—just re-built at great cost, and probably the handsomest in the State—and continued their fiendish work. …" (Manchester Union Democrat, July 5, 1854). These anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic sentiments swept the Know-Nothing American Party into power in the Massachusetts state legislature in 1854. "While much of the American Party’s platform was socially progressive, its highest priority was reducing the influence of Irish Catholic immigrants, and the party became the home of wildly divergent social movements attempting to organize under one political umbrella....The Massachusetts Know Nothing legislature appointed a committee to investigate sexual immorality in Catholic convents, but it was quickly disbanded when a committee member was discovered using state funds to pay for a prostitute." (Historic Ipswich blog entry on the Know Nothings) By 1858, however, the new party was a spent force, and was defeated in almost all local and state elections. It also did little to thwart the continued growth of the Catholic Church in Massachusetts and New England, as Irish immigrants continued to pour in while their church organized itself under Irish leadership. Later, Irish domination of the Church hierarchy led to resentment by other, later Catholic immigrant groups, such as Italians and French Canadians - that topic will be covered in a blog entry about "National Parishes". Map showing concentration of Irish-born in 1880. Note Massachusetts. My own theory is that the Catholic Church of the Irish variety flourished in New England despite considerable native animosity in from the 1830s through the Civil War, because of a long history in Ireland of persevering under conditions of adversity and oppression.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed