|

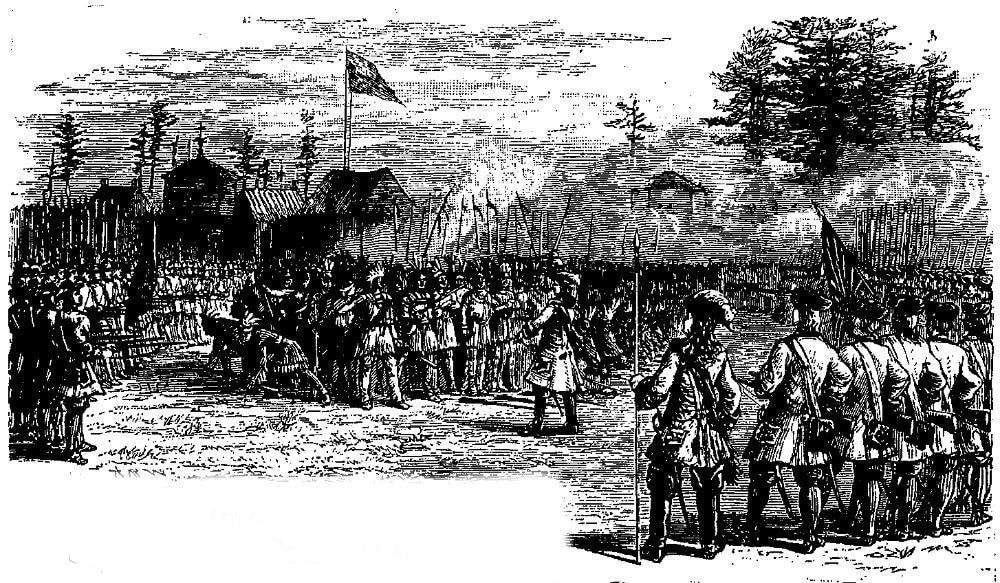

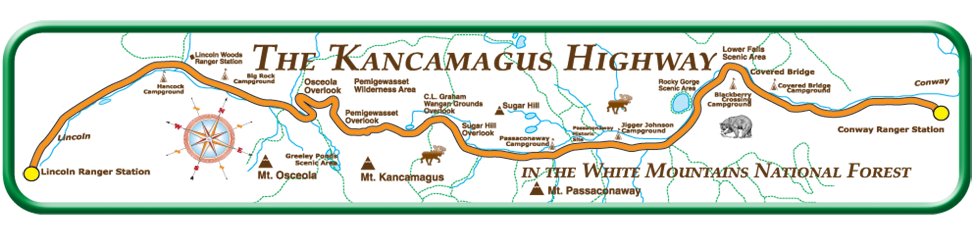

Below: John Greenleaf Whittier. Source: Wikipedia I'm supposed to do 52 profiles of ancestors in 2018 and I'm falling behind! So here is #8: John Greenleaf Whittier. He's a nearly forgotten poet who in his day was a household name. This was back before radio or TV, when people read (to themselves and to each other) for entertainment. John Greenleaf Whittier is not my ancestor. He can't be. He never had children. We are however, related...his great grandfather Joseph Whittier (1669-1717) of Haverhill is my eighth great grandfather. This makes us second cousins seven times removed. Say that ten times fast! Because he has been an important source for me in learning old stories of the area, I decided to include him in the 52 ancestors list. Below: John Greenleaf Whittier birthplace, Haverhill, Mass. (Source: Hampton N.H. Historical Society) Above: John Greenleaf Whittier Home and Museum, Amesbury, Mass., where he lived for over fifty years. Source: museum website So who was this guy, famous enough to have two historical museums in the area, one in Haverhill (where he was born) and one in Amesbury (where he lived when he was famous)? Basically, he was a self-educated farmer who lived in an ancient farmhouse in Haverhill - it was already well over a century old when he was born there in 1808 - that had been built by one of the founders of Haverhill. He wrote a lot of poetry, and was involved in the movement that wanted to abolish slavery in the United States. This activity got him into the circle of famous abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who was editor of a newspaper in Newburyport for a time. This newspaper started publishing Whittier's poems, and later when Garrison got more famous and began running in literary circles, he was able to promote Whittier. He became famous as a result of his poem Snowbound, about being snowed in. It starts like this: "The sun that brief December day Rose cheerless over hills of gray, And, darkly circled, gave at noon A sadder light than waning moon." Based on his literary fame for this and other poems, he eventually received an honorary degree from Harvard. Whittier himself barely left the area around Haverhill, other than a couple years in Philadelphia and New York when he was a young man. He complied lots of the historical stories of the Merrimack Valley area into poems. I have written blog posts about some of these topics, such as the story of Captain Waldron's deceit of the Indians and their revenge upon him; and the story of the Pennacook Indian princess Wenunchus, who drowned in the Merrimack as a result of a squabble between her father Passaconnaway and her husband Winnepurkett of Saugus. Back in Whittier's day, poems were sometimes epics, running thousands of lines. People would read them outloud to each other in the evening by lamplight or by the fire. I recorded myself reading The Bridal of Pennacook (in part), to get a feel for the language. That poem also provided a good geography lesson about upper reaches of the Merrimack River, which was the heartland of the Pennacook indians. The poem mentions Turee's brook, Contocook, "the Crystal Hills to the far southeast", Sunapee, Snooganock, Coos, Umbagog Lake, Ammonoosuc, Chepewass, "the Keenomps of the hills which throw/Their shade on the Smile of Manito"; Kearsarge, Babboosuck brook, Otternic, Sondagardee, Squamscot, Piscataquog...does anyone know these places??

2 Comments

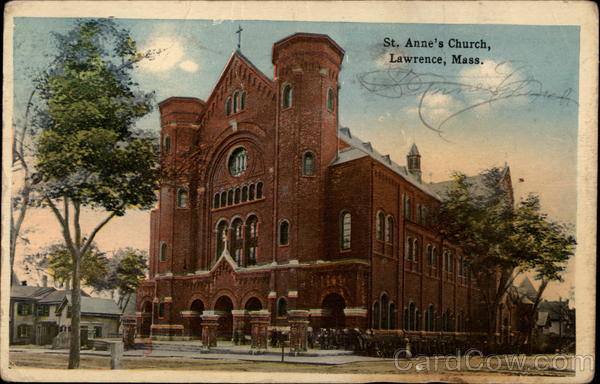

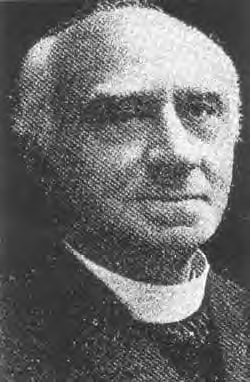

St. Anne's Church, the Society of Mary (Marists) and the French Canadians of Greater Lawrence3/7/2018 Above: St. Anne's Church, Lawrence. Completed 1883, closed 1991 The French Canadians in Lawrence "Although less numerous in Lawrence than in Lowell, the French Canadians still contribute an important element to the Catholic population of this city." (from Byrne's History of the Catholic Church in New England, 1899) As described in another blog post, French Canadians began emigrating to manufacturing centers in New England after the Civil War. They brought with them a concept of La Survivance, an insistence on maintaining their French language and their culture, expressed to a large degree through their own Catholic institutions: French churches and French schools. The French-speaking Canadian immigrants were comprised of Québécois from the province of Quebec; and Acadians, the descendants of French-speaking settlers of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia (many of whom were forcibly moved to Louisiana after defeat by the British in 1755, where they became known as Cajuns). A French Parish One of the first things the French-speakers did in Lawrence was to create their own parish. This was no easy task. The Augustinian order was firmly in charge of the churches on the north side of the Merrimack River. So-called national parishes (foreign-language churches that catered to specific ethnic groups) in Lawrence were usually organized as mission churches of St. Mary's parish. St. Mary's was the main "cathedral", run by the Augustinian Fathers. Thus, the German-speaking Church of the Assumption, the Polish-speaking Holy Trinity Church, the Lithuanian-speaking St. Francis and the Portuguese-speaking Sts. Peter and Paul were all mission churches of St. Mary's, and were overseen by the (Irish-dominated) Augustinians. In contrast, through the importation of recognized French-speaking religious orders, the French were allowed to have their own independent parish in the Lawrence area. Eventually, St. Anne's parish grew to encompass four churches: St. Anne's, Sacred Heart in South Lawrence, Our Lady of Mount Carmel (Methuen) and St. Theresa (Methuen). All were essentially founded by the Marist Fathers, and in most cases were run by the Marists for decades, along with St. Joseph's in Haverhill, as further described below. The Marists come to New England The order was formally recognized by the Church in 1822. It was formed after a group of soon-to-be priests led by Jean-Claude Courveille and Jean-Claude Colin made a pilgrimage to the shrine of the Black Virgin at the cathedral of LePuy in France. There, they experienced healing while praying before the statue of the Virgin. They came to believe the Blessed Mother wanted to help the Church through a society consecrated to Mary and bearing her name. The Marists' first missionary work was in the remote areas of the Diocese of Belley in southeast France. The Marist order (not to be confused with the Marianist order), first focused their American mission in Louisiana, a bastion of French Catholicism, taking charge of St. Michael's in Convent, Louisiana in 1863 and overseeing two parishes and a high school. The fact that they arrived during the Civil War did not seem to dissuade them. Until 1880, the Marists were content mainly to operate in France; however, in that year, citing the principles of the French Revolution, the government of France ordered the closure of all Catholic religious orders in France. "With the expulsion of religious orders from France in 1880, the Marist General Administration sought new opportunities for their members in the United States. There were more opportunities than they could handle, but no more than in the New England states, where French-Canadians were pouring in to find employment in the mills that had sprouted up all over the area." (From the 150th Anniversary pamphlet of the Marist Order, www.societyofmaryusa.org/pdfs/Marist150YearsofGrace.pdf) The leadership of Rev. Elphage Godin, S.M. Like Rev. James O'Donnell, O.S.A. who brought the Augustinians to Lawrence, and Rev. Andre-Marie Garin, O.M.I., who led the expansion of the Oblates in Greater Lowell, Rev. Elphege Godin, S.M., was a larger-than-life figure. Above: Father Elphege Godin, S.M. (from the Society of Mary website) Born in 1847 at Trois-Rivieres, P.O., Canada, Father Godin was ordained in 1871 for the diocese of Trois-Rivieres (Quebec), where he served for several years. He joined the Society of Mary in France in 1878. (Source: Marist 150th anniversary pamphlet.) His first assignment as a Marist was to teach at Jefferson College in Convent, Louisiana, and to preach parish missions. Able to speak English as well as French, his services as a preacher were much in demand. In the early part of 1881, he was invited to preach in Old Town, Maine, and spent some time as a missionary in Waterville, Augusta, Biddeford and Brunswick, Maine, and also in Manchester and Lebanon, N.H. In May of that year, Father Olivier Boucher, the pastor of St. Anne’s in Lawrence, MA asked his assistance. (ibid.) Completion of St. Anne's Church "In 1869 there were only four hundred French Canadians in Lawrence. They were given religious instruction in their own language in the basement of the Immaculate Conception church. [Note: the so-called "basement church" for ethnic immigrants is still a practice today in the Catholic Church.] Knowledge of the success achieved by the French Oblates in Lowell reached them, and a movement was begun which resulted in a visit from [the Lowell-based Oblate] Father Garin, and the holding of regular services in Essex Hall." "In 1882...Rev. Elphage Godin, the well-known Marist...entered upon his duties in this important centre of French Canadian colonization. Under his management the church was speedily finished and dedicated, the ceremony being performed by Archbishop Williams on Low Sunday, 1883." (from Byrne's history of the Catholic Church in New England, 1899) "It is generally agreed that St. Anne’s Parish in Lawrence was the ‘Mother Parish’ of all Marist-operated parishes in New England." (www.societyofmaryusa.org/about/history-northeast.html) St. Anne's was followed by the establishment of Marist-run missions that became four French-speaking parishes in the Greater Lawrence area: Sacred Heart (Marist-operated for 101 years), St. Joseph (85 years); and in Methuen, Our Lady of Mount Carmel (78 years) and St. Theresa (61 years).(Ibid) Below: A 2015 picture of Sacred Heart Church, South Lawrence. Source: Wikipedia The Marist Fathers provide additional French-focused churches in the area Sacred Heart An 1899 history of the Catholic Church in New England noted that St. Anne's church was bursting to the gills with worshipers. This problem was remedied with the construction of Sacred Heart in South Lawrence, which eventually became a grand complex. The first church on the site was built in 1905, apparently being replaced by the current church starting in 1916. "The oldest building on the site is the 1899 school, a three-story, highly ornamental brick structure designed in the Romanesque Revival style. The convent, rectory, and second school were built in 1920, 1924, and 1925, respectively. The ground level of the church was constructed in 1916 as a one-story brick structure, but between 1934 and 1936, the original church was incorporated into a Gothic Revival-style building constructed of polychromatic ashlar." (Source: Sacred Heart Complex Approved for Nomination to the National Register of HistoricPlaces, https://www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcpdf/pressreleases/91911_Sacred_Heart_Complex_Lawrence.pdf) Sacred Heart was closed in 2005 and has since been taken over by a Catholic-inspired group not affiliated with the Catholic church, who hold Latin masses in the facility. St. Joseph's, Haverhill St. Joseph Church was founded in 1871. It was Marist-run from 1893 for eighty five years, when Father Godin became the superior, until 1978. "In the year 1870 the French Canadians of Haverhill were numerous enough to found a St. Jean Baptiste Society, whose president was soon deputed to visit Bishop Williams [in Boston] and request the services of a Canadian pastor. Through the efforts of Father Garin, of Lowell, an Oblate priest, Rev. Father Baudin, was sent to the town on Christmas Day, 1871. A hall on Water street had been fitted up as a chapel, and in that humble edifice Father Baudin held services and baptized two children. This was the foundation of the present flourishing parish of St. Joseph." (Source: Byrne's history of the Catholic Church in New England, 1899) A more imposing edifice was constructed in 1876. "The growth of the congregation, both by new arrivals from Canada and by local increase, compelled the erection of a church and at the same time made it financially possible. December 17, 1876, Archbishop Williams blessed the edifice which stands on the comer of Grand and Locust streets, and administered confirmation to nearly a hundred persons." (Ibid.) At some later date, the church on Bellevue Avenue was constructed, which stands to this day. Father Godin served for ten years at St. Joseph, firmly establishing the Marist presence, which continued under the tutelage of that Order until 1978. The French parish was closed in 1998, when St. Joseph merged with three other formerly ethnic parishes of the Mount Washington neighborhood: St. Michael (Polish), St. George (Lithuanian) and St. Rita (Italian). The combined new parish, All Saints, is housed in the former St. Joseph's building on Bellevue Avenue. The elementary school at St. Joseph's was the subject of a legal dispute when an anti-immigrant, pro-American Haverhill School Board ordered all schools to teach only in English in 1888. At the time, instruction was being given in French by Les Soeurs de la Charité d'Ottawa (Soeurs Grises de la Croix), the so-called Grey Nuns of the Cross from Ottawa. This incident will be covered in a separate blog entry, as will be the Grey Nuns, who had a prominent role in the Merrimack Valley including running the main hospital in Lowell for a century. St. Theresa’s (St-Thérèse) and Our Lady of Mt. Carmel (Notre-Dame du Mont Carmel), Methuen Above: St. Theresa, Methuen. From Our Lady of Good Counsel website Our Lady of Mt. Carmel was built in 1922 as the first French-Canadian church in Methuen, as a "mission church" of St. Anne's In the mid-1930s, the Marist Fathers established a second mission church, St. Theresa, to serve the growing French Canadian population there. Our Lady of Mt. Carmel closed in 2000. The ministry of St. Theresa's was eventually taken over by the Augustinians, and the church was merged with St. Augustine's in Lawrence (my church growing up) to form Our Lady of Good Counsel parish. They are apparently now under diocesan tutelage. The Novitiate in Tyngsboro, Mass. In 1922, the Marists purchased a portion of Wonalancet Farm in Tyngsboro, a suburb of Lowell. You may remember from other blog posts that this is where the hapless Wonalancet, sachem of the Pennacook Indians, lived out his days under the watchful eye of Captain Tyng following King's Philips War of the mid 1670s. They initially used the historic Tyng house, pictured below (which burned down in 1981) before building a more modern set of structures. Below: The historic Jonathan Tyng house, built circa 1675, burned down 1981 Above: The Marist novitiate (for training new members of the Order), late 1960s (source http://academic2.marist.edu/foy/maristsall/essays/innovation_academy.html) After World War 2, the Marist Order decided to establish a college in the United States, and the location was either going to be in Poughkeepsie, New York, where they had a large Novitiate, or in Tyngsboro at this site. Marist College was ultimately established in Poughkeepsie. If it had been established in Tyngsboro it no doubt would have been a rival of Merrimack College, the Augustinian college in North Andover. In 1979, following a significant decline in new members to the order, the Marists sold the Tyngsboro property to Wang Laboratories, who used it for their Wang Institute until 1988, when it was sold to Boston University as a corporate campus. In 1996, a charter school, Innovation Academy, began operating on the property and they apparently bought the land outright in 2008. Legacy of Father Godin "Father Godin was a Marist pioneer who planted the seed, nurtured and cared for it while it grew and, by the time he took leave of this earth, saw it firmly established. When he began at St. Anne’s in Lawrence, MA, in 1882, this was the only house the Marists had in the whole northeastern section of the country. When he died, 51 years later, in 1931, besides St. Anne’s the province included Our Lady of Victories, Boston, MA; St. Bruno’s, Van Buren, ME, St. Mary’s High School, Van Buren, ME, St. Mary’s College, Van Buren, ME (1887 to 1926), St. Joseph’s, Haverhill, MA, Our Lady of Pity, Cambridge, MA, Sacred Heart, Lawrence, MA; Immaculate Conception, Westerly, RI, St. John the Baptist in Brunswick, ME, St. Charles Borromeo in Providence, RI, St. Remi’s, Keegan, ME, a novitiate on Staten Island, NY, and two minor seminaries: one in Bedford, MA and one in Sillery, P.Q. Canada." Sadly, the time of his death marked the beginning of a long decline of the French-speaking churches of the Marists, most of which have since closed as a result of significant postwar demographic changes. A remaining institution of prominence is the Lourdes Center in Boston. "In Kenmore Square, the Marist-run National Lourdes Bureau of America, founded in 1950 by the Marists at the request of Archbishop Richard Cardinal Cushing, and through arrangement with the Bishop of Lourdes, France, mails out an average of 22,000 small bottles of Lourdes water every month. The ministry also publishes a bi-monthly newsletter to 47,000 readers, sponsors annual pilgrimages to Lourdes, and conducts daily Mass and confessions for students, residents, hotel workers and guests, as well as shoppers and visitors to the Kenmore Square area." (Source: Boston Pilot article, February 20, 2015) Below: 1950 Banquet to celebrate the cherished Marist Fathers of St. Anne's School, held in the gym at Central Catholic High School. Source: Lawrence History Center The Marist Brothers and Education The educational legacy of the Marists in Greater Lawrence is as important as their ecclesiastical legacy. Unlike some of the other religious orders, the Marists were strongly represented by brothers, who had taken vows but were not ordained priests. The Marist brothers were typically educators at the primary and secondary level. The educational attainments in the Merrimack Valley of the Marist Brothers will be covered in a separate blog entry. Their crowning legacy was probably Central Catholic High School, which was essentially spun off of the St. Anne's School of Lawrence by Brother Mary Florentius in 1935. Below: Central Catholic High School, Lawrence. It is still a Marist institution.  Other French-Canadian Institutions in Lawrence The Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste was once to the Franco-American community what the Knights of Columbus was to the Italians or the Hibernians was to the Irish. The Social Naturalization Club was founded in 1915. Located on Lowell Street in Lawrence, it hosted prominent political leaders, like Rose Kennedy in 1962 and Mrs. Joseph P. Kennedy in 1985. Later it was located at 120 Broadway. The LaSalle Social Club on Andover Street in Lawrence was another prominent Franco-American social institution. The community also had a French paper of their own, Le Progres. [Please help me add to this list.] Above: the interior of St. Anne's church, Lawrence, 2016. It has basically been abandoned and neglected since it closed in 1991. Source photo: Eagle-Tribune

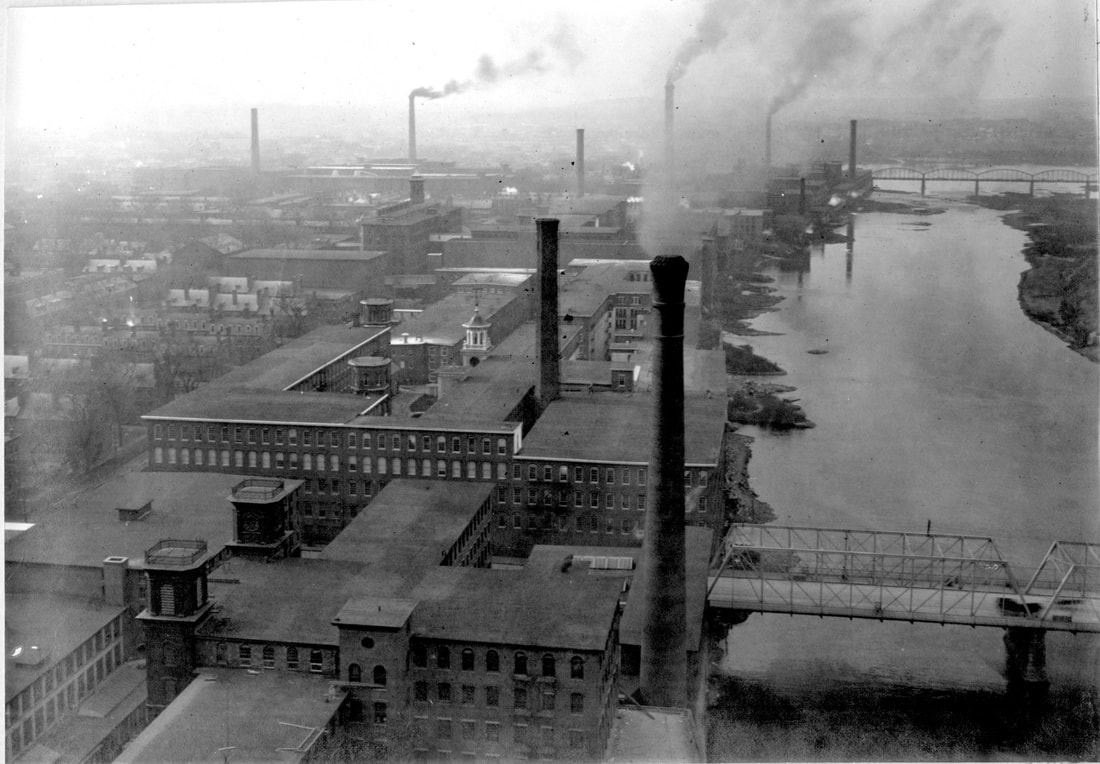

Above: Lowell in its manufacturing heyday. Source: UMass Lowell Introduction: Lowell before the French Everyone knows the story of Lowell's original workers, Yankee-farm girls who worked in the textile mills to earn a little money before returning to rural farms to get married. Introduced in 1826 upon the founding of Lowell, this system of labor collapsed when destitute Irish immigrants poured into the area following the Potato Famine. These poor Irish provided cheaper labor under worse conditions than the mill girls could ever tolerate. A few decades after their arrival in Lowell and other cities, the Irish had established a foothold, basically creating the Catholic Church in New England along the way. They also began to participate successfully in local politics. By 1882, Lowell had an Irish-American mayor. In the Merrimack Valley and elsewhere, later generations of immigrants, usually Roman Catholic, had to contend with Irish dominance of key institutions in the Church and the local government. This will be covered in other blog posts. The first immigrant group after the Irish in the Merrimack Valley were the French-Canadians. They are also the only immigrant group to arrive by train. French-Canadian Immigration French Canadian immigrants had been crossing the border into the United States since the 1840s, searching for better farming conditions and settling along the northern reaches of New York State, Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine, where in some towns they comprised the majority of the population by the time of the Civil War. However, after the Civil War, migration patterns focused on New England's growing manufacturing centers. French-Canadians ultimately were concentrated in Fall River, Lowell, Manchester (N.H.), Woonsocket (R.I.), New Bedford, Holyoke, Worcester, Lewiston (Me.), Biddeford (Me.) and a few lesser manufacturing towns. (Source: The French Canadians in New England, by William MacDonald, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 12, No. 3 (Apr., 1898), pp. 245-279, Oxford University Press.) Lowell had a total population of approximately 41,000 in 1870, of which 3,000 were French-Canadian, compared to around 20,000 Irish. By 1881, there were approximately 10,000 French Canadians, showing the tremendous rate of immigration. By 1909, the number of French Canadians had nearly caught up to the number of Irish (including in both cases children of immigrants): 20,000 versus 22,300. (Source: The Record of a City: A Social Survey of Lowell, Massachusetts, George Frederick Kenngott, Macmillan Company, 1912) In Lowell, like elsewhere, French Canadian immigrants adhered to the ethos of la survivance:

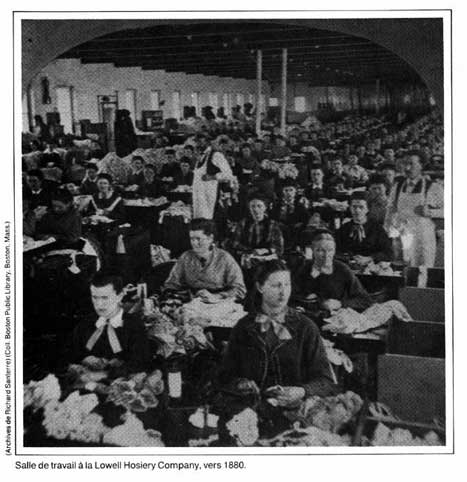

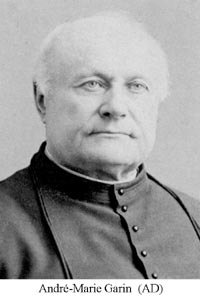

(From French Canadians in Massachusetts Politics, 1885-1915: Ethnicity and Political Pragmatism by Ronald Arthur Petrin, Balch Institute Press, 1990) La Surivance led the French-Canadians to insist upon their own institutions, and it ended up being the Oblates (and a number of other French-speaking religious orders such as the Grey Sisters of Ottawa) who provided them. Below: French-Canadian women at work in a Lowell hosiery factory, 1880.  Left : The heart of Little Canada, Hall & Aiken Streets, Lowell, 1923. Source: Lowell Sun The "Little Canada" of Lowell was pretty much one of these "dismal proletarian districts". It was situated along the Merrimack River in central Lowell, behind the textile mills around Aiken, Austin, Cheever, Hall, Tucker, Ward, Ford, Decatur, Race, Merrimack and Moody Streets. Below: The memorial plaque for Little Canada (Le Petit Canada), the core French-Canadian neighborhood of Lowell, Aiken Street. The neighborhood was demolished for urban renewal in 1964. It was into this area (and nearby French-Canadian neighborhoods) that the Oblates came in 1868, to serve the religious and cultural needs of the burgeoning French-Canadian population of Lowell. The Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate The Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate (OMI) was founded in 1816 by Saint Eugene de Mazenod, a French priest born in Aix-en-Provence in the south of France. In 1841, Canada became their first foreign mission. With steady reinforcement from France and Canadian recruits, they moved up the Ottawa Valley, and in 1845 into the North-West, where the establishment of the Catholic Church in western Canada was largely Oblate work. Coming to the United States and Lowell By 1853, the Oblates were following the French speaking population into the United States, setting up a mission in Plattsburg, New York, followed by one in Buffalo, New York. By 1857, they oversaw St. Joseph's in Burlington, Vermont. In December 1867, Father Florent Vandenberghe, provincial superior of the Oblates, based in Montreal, met Archbishop John J. Williams of the Archdiocese of Boston while attending the dedication of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Burlington, Vermont. Arrangements were made for two Oblate priests to be sent to Lowell at the invitation of the Archdiocese, to minister to the growing French Canadian population. Below: Father Florent Vandenberghe of Montreal, Provincial Superior of The Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, who directed two Oblate priests to Lowell in 1868 Founding of St. Joseph's and Immaculate Conception churches (both still active today) Following their conversation in Burlington, Archbishop Williams had been active, and found a former Unitarian Church on Lee Street, Lowell, for which he entered negotiations, hoping it would be the future site of the Oblates' parish. In March, when weather conditions improved, Father Vandenberghe traveled with Bishop Williams to view the site, but expressed some concern about the ability of the small French Canadian population there to sustain a parish of its own. This prompted Bishop Williams to propose that the Oblates establish two parishes, the second an English-speaking parish, to which Father Vandenberghe agreed. Father Vandenberghe sent two priests, Fathers Andre Garin and Father Lucien Lagier, who arrived in Lowell on April 18, 1868. Within a few short weeks, the Canadian Catholics contributed enough money for a down payment on the Lee Street Church, and dedicated it to St. Joseph on May 3, 1868, the city's first French-speaking parish. The second parish agreed to was temporarily located at St. John Chapel, initially part of St. John Hospital (then at the corner of Fayette and Stackpole Streets and now part of "the Saints" campus of Lowell General Hospital), and dedicated to the Immaculate Conception. (Source: Oblates Come to Lowell to Serve French Canadian Catholics, by Thomas Lester, Friday, January 19, 2018 https://www.thebostonpilot.com/opinion/article.asp?ID=181298) Below: Immaculate Conception, East Merrimack Street, Lowell (rebuilt after fire 1912-1916). Source: Wikipedia Despite the successful foundation of two churches, it was soon determined that the heart of the neighborhood lacked a church. The aforementioned Father Garin made it his life's work to establish a church there, dedicated to St. Jean Baptiste. Below: Fr. Andre-Marie Garin, OMI, "L'inoubliable Fondateur" "Father Garin was a native of France, and a missionary worthy of comparison with Marquette, Breboeuf, and others whom that ever-vital nation has sent to our shores. He had traveled by canoe and snow-shoe through Labrador, and on the coast of Hudson's Bay; had lived without food for forty-eight hours on an ice-floe; and had translated books into rare Indian tongues. His vigorous presence aroused the Canadians of Lowell." (from The History of the Catholic Church in the New England States, Volume I, by Rev William Byrne et al, 1899) Like Father O'Donnell who basically founded the Augustinian presence in nearby Lawrence, Father Garin was a larger-than-life figure so needed by recent poor immigrant communities. In 1869, Father Garin performed the first French language Mass in Lawrence, where the French speaking population still only numbered in the hundreds. In due course, another French-speaking religious order, the Marists, would take over the French parishes of Lawrence. That is the subject of another blog post. In 1893, he was chosen as the delegate to the meeting of the General Chapter of the Oblates in France. Then he turned his attention to completing St. Jean Baptiste. Establishment of St. Jean Baptiste The new church was part of St. Joseph parish. "St. Joseph would be expanded several times in the following years, but never proved adequate for the burgeoning French-speaking population in the Lowell area. To solve this problem Father Garin hoped to build a new church, and in 1887 purchased land on Merrimack Street on which to do so, the eventual site of St. John the Baptist, dedicated on Dec. 13, 1896." "Sadly, Father Garin would not live to see its completion, having died the year before on Feb. 16, 1895. At the time of his arrival in 1868, there were 1,200 French-speaking Catholics in Lowell, and by the time his new church was completed, it was responsible for serving close to 20,000." (Source: Byrne history, 1899) The church was located in the heart of Little Canada and served as the focal point of the community for decades. "St. John the Baptist's church, which is now the principal French church of Lowell, being fully as large as St. Joseph's, and much more imposing, fronts on Merrimack street, somewhat west of St. Joseph's. It is a bold Romanesque structure, built of granite, the prevalent material in Lowell public buildings. A bronze statue in front immortalizes the resolute features of its founder, Father Garin." (Ibid.) As noted by Byrne in his history of the Catholic Church in New England, "The French church is popular even among the Irish-Americans of Lowell, numbers of whom attend its services. Attendance of Canadians, however, at the services in churches other than their own is rare." With the destruction of the Little Canada neighborhood in 1964, following years of population decline as post-war populations moved to the suburbs, in 1993 St. Jean Baptiste was closed by the Archdiocese. It was then resurrected as the sole Spanish-language "national parish" church in New England (see below), which was closed in 2004. The structure still stands and is being converted to an event space. Below: Recent Photo of St. Jean Baptiste, now an event space. Source: https://www.lowellshistoriccathedral.com/ Creation of a separate OMI Province in 1883 "This high esteem which the Oblates enjoyed here, and the success of their missionary tours, addressed to the needs of French and English congregations elsewhere, led to the creation, in 1883, of a separate province of the Order for the United States, with its headquarters at Lowell. In the same year a novitiate was founded in the suburb of Tewksbury." (covered below)(source: Byrne 1899 history) Establishment of Notre Dame de Lourdes in 1908 "At the dawn of the [twentieth] century, the need for a church in another section of the city became acute. Many of the Franco-Americans who lived some distance from St. Joseph’s Church were abandoning their religious practices. Despite their relative poverty, the people organized and founded Notre Dame de Lourdes parish in 1908 after restoring an abandoned Baptist temple. A new and modern church complex was constructed in 1962. For many years, while serving the community, the parish was greatly involved with ministry to the many immigrant minorities in the area. A special center reached out to the needs of the many Southeast Asians who have been migrating to Lowell since the war in Vietnam. The church was an active member of many interfaith social programs that reached out to the needy of that part of the city. (Editor’s Note: Following the reconfiguration of the Archdiocese of Boston, Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes was suppressed in 2004.)" (Source: https://francolowellma.wordpress.com/religious-orders/oblates-of-mary-immaculate/) Establishment of Ste Jeanne d’Arc Parish in 1922 "St. Jeanne d’Arc Parish was established on December 30,1922, by William Cardinal O’Connell. The Oblates of St. Joseph Parish had been ministering to the Franco-Americans on the Pawtucketville side of the Merrimack River area since 1920. A small school, built in 1910 by Father Campeau to accommodate younger children, was expanded and transformed into a school and chapel. The first Mass was celebrated there on the third Sunday of April 1921. By a decree of the General House, dated January 30, 1923, Father Léon Lamothe was appointed first Superior and the new residence was officially established. A new stone church was completed in 1929. Later, a new slanted roof was added to improve the outside lines of the structure, and the interior of the church has been completely renovated in conformity with the latest liturgical requirements. (Editor’s Note: As a result of the reconfiguration process, the Archdiocese of Boston ordered the suppression of Ste-Jean d’Arc parish in 2004. Ste-Jeanne d’Arc grammar school, administered by the sisters of Charity of Ottawa is still active and currently operates under the auspices of St. Rita’s Parish.)" (Source: https://francolowellma.wordpress.com/religious-orders/oblates-of-mary-immaculate/) The Oblates in Billerica - St. Andrews "Before Saint Andrew’s Parish was established [in North Billerica], thousands of Irish people, due to political oppression along with the great potato crop failure of the 1840’s and 1850’s, [had] made the trek to New England in order to seek jobs in the nearby Talbot and Faulkner mill complexes. They brought with them few material possessions, but they did bring with them a sound and living faith. These Billerica Catholics had to walk about five miles to the nearest Catholic church in Lowell to worship. In 1868, the remarkable Father Andre Garin of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate established a mission parish for the town of Billerica. He helped the small congregation arrange to buy the now-abandoned Universalist church. After the purchase, they moved it to Mill Street, now known as Rogers Street, and placed it under the patronage of the Apostle Saint Andrew. In the end, $4000.00 had been spent; but the people finally had their own church. For forty years, Saint Andrew’s Parish was in the care of the Oblate Fathers. They would come in from Lowell, at least once a month, to celebrate Mass and handle all pastoral matters. Some of these priests served for but a few months, while others remained for several years. In 1890, Father James Maloney, O.M.I. realized the need for enlarged facilities to accommodate the increased number of parishioners. His program of renovation and expansion was carried out with the physical as well as the financial help of the people. Through their generosity and selflessness, the dedicated people managed to complete a $6,910.44 renovation that increased the size of the church by one third. Imagine the sacrifices that were made considering that the average daily wage was about 85 cents!" From http://billericacatholic.org/?page_id=49 The Oblates in Tewksbury Above: The Former Oblate Fathers Novitiate

In 1883, the Oblates in Lowell founded a Novitiate, an institution typical of any Catholic religious order, in which Novices are trained and decide whether they are called to the order, either as priests or as lay members (monks and nuns). These days, it is a retirement home for Oblate priests from around North America. The Oblates and Spanish-speaking Catholics of Lowell, 1970-2004 When the first wave of non-English speaking Catholics arrived with the French-Canadians, these French-language Catholics were able to bring religious orders from Canada such as the Oblates and the Marists, to provide French language instruction. Subsequently, in the 1890s through the 1920s, the archdiocese allowed the formation of "national parishes" dedicated to the needs of a particular ethnic group, Italian, Polish, Portuguese and what have you, although they were typically run by diocesan priests of Irish background. After World War II, the "national parish" practice largely ended as these immigrant groups all became assimilated and many moved to suburbs, leading to the closure of ethnic parishes in inner cities. When Puerto Rican and other hispanic immigrants began arriving in the Merrimack Valley in the early 1970s, it triggered a debate within the Archdiocese: do we establish a separate Spanish-language national parish? Eventually the answer was: no. Integration was seen as more favorable --although (begrudging?) accommodations were made in allowing "basement chapels" to be formed where worship was conducted in Spanish. The sole exception to this rule was a Spanish-language parish in Lowell, Nuestra Seniora del Carmen, in the former St. Jean Baptiste church.

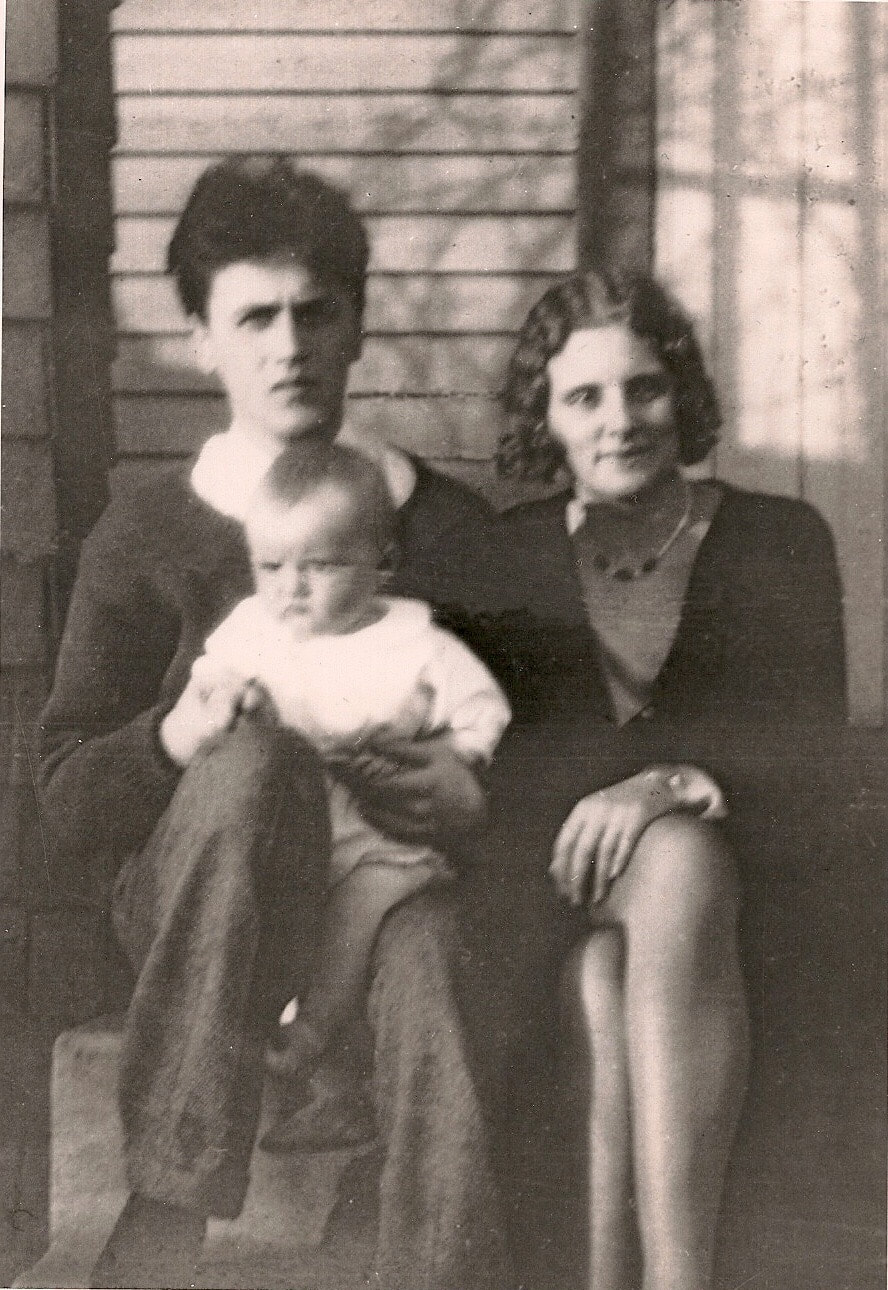

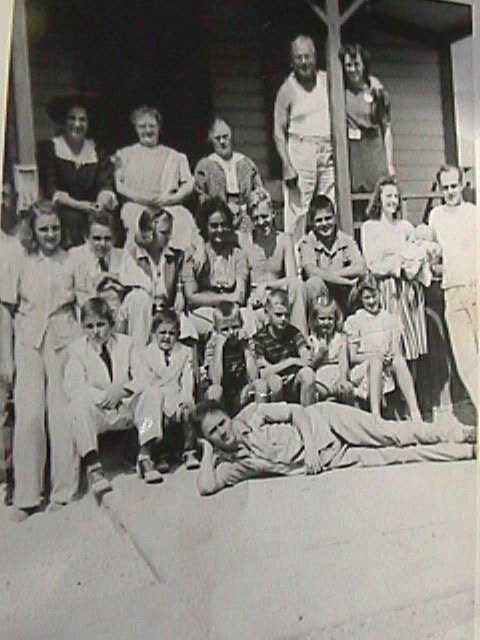

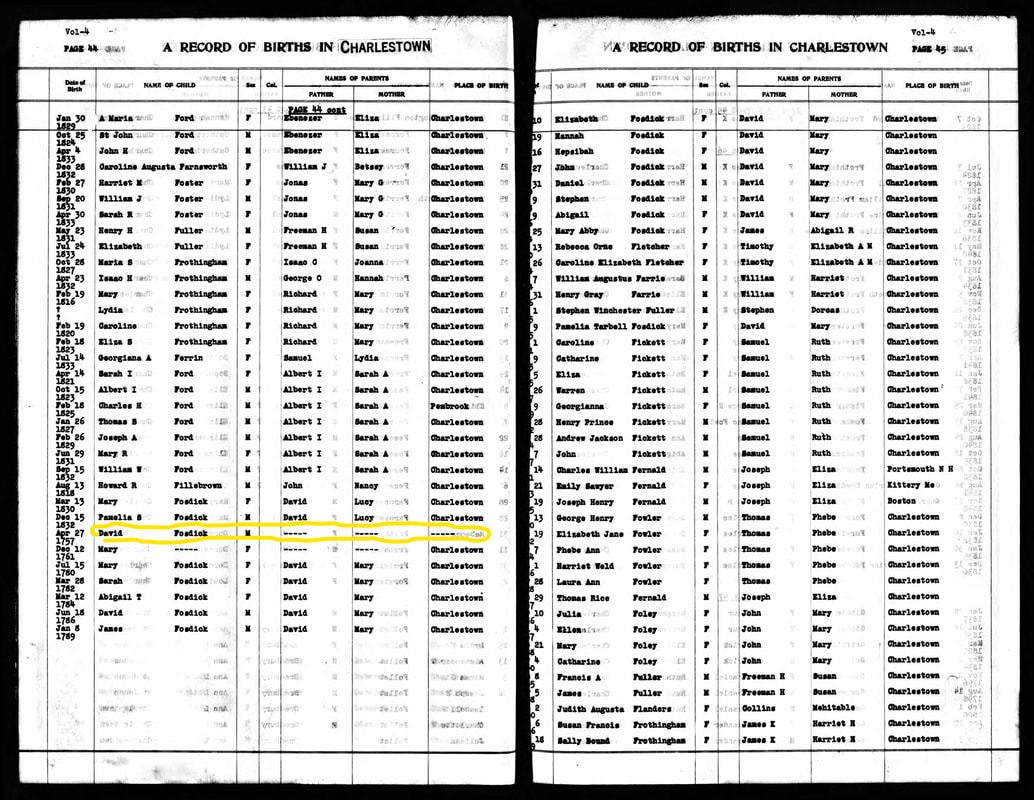

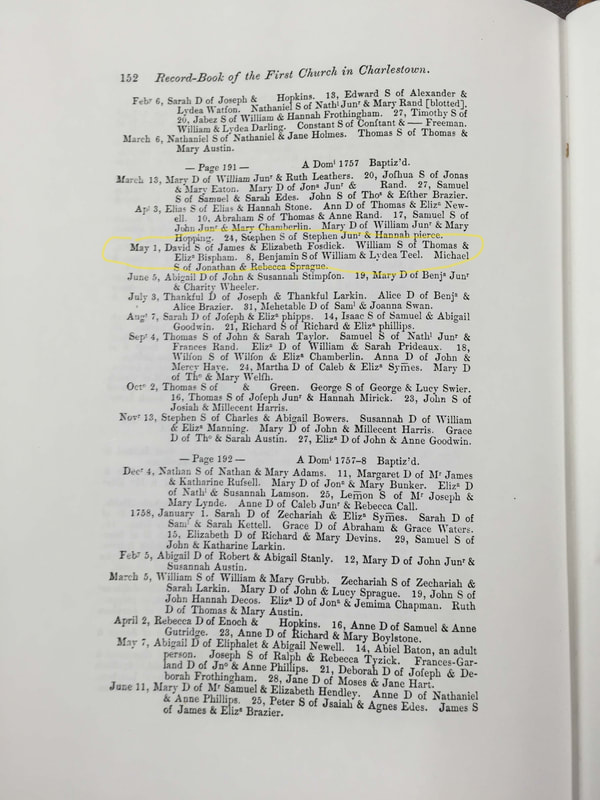

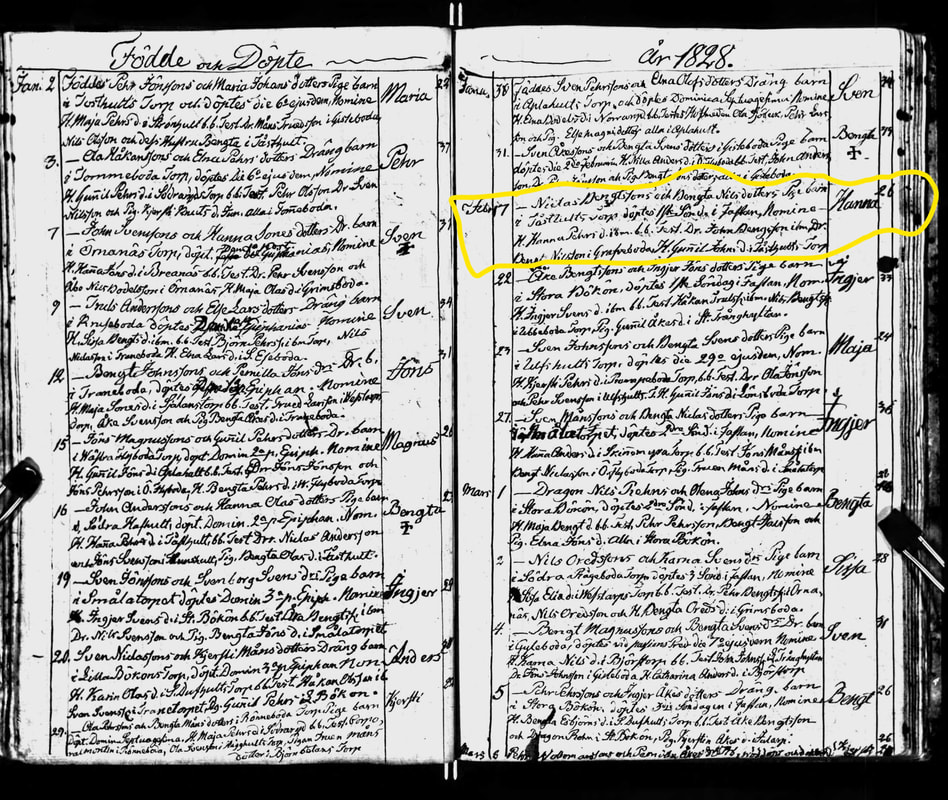

#52Ancestors challenge, week 7: My grandfather illustrates the industrial heritage of three towns2/18/2018 Below: My grandfather Clifford McCarthy, age 18, my grandmother Gladys Johnson, age 17, and my father, late autumn 1930(?). Recently, I asked my father to describe the work history of his father Clifford, who was born in Lawrence in 1912. Clifford married his high school sweetheart Gladys Johnson on his eighteenth birthday, February 3, 1930. She was four months pregnant with my father. They found a minister to do the wedding on the quick, in North Reading a few towns away. The stock market crash had been the previous October, before which Clifford's prospects seemed very different. Now, he was a married man with a family to support. Banks were failing and employers were closing. The Great Depression was descending over everything. He took his high school diploma that spring at Lawrence High and went to work. Below: The Kuhnardt Mill in Lawrence around 1930 judging by the cars in the background. This building still stands today. Source: Lawrence History Center .According to my father, "The first job of my dad’s, as I remember, from my pre-school days, was as a jig operator in the dye house at the Kuhnardt Mill by the Duck Bridge on the north side of the Merrimack River [in Lawrence]. His boss was his brother-in- law Wiliam Howarth. I heard complaints (from my mother?) that Bill picked on him." This was one of the stories of my grandfathers' employment history, working for in-laws who got him jobs. Later, he got a job with the Boston & Maine railroad through his father-in-law, who was an engineer. Years after that, in 1949, my father got a job working for his uncle Bill Howarth. It was at a dye house in Peterborough, New Hampshire. They were both working there because the mills in Lawrence were laying people off. Soon, the dye house in Peterborough also closed, and Bill Howarth moved to North Carolina to follow the textile industry south. But I digress... Because it was the Depression, there were times when my grandfather was laid off. "We received free flour from some source and my mother made "Johnny Cake” with it, which I liked," said my father. This is when New Deal programs allowed my grandfather to earn a wage. "He also worked with the WPA during the 30s. l distinctly remember a WPA arm band. I think he was involved with building side-walks, pick-and-shovel work." My father thinks he was part of the team of WPA workers that built Den Rock Park in Lawrence. Below: A bridge in Den Rock Park, Lawrence, Mass., that was likely built by WPA workers in the 1930s. The park sits at the intersection of Lawrence, Andover and North Andover My grandfather's next two factory jobs were in Andover, where by happenstance my father also was born a few years previous. "Thereafter as I remember it both parents worked a spell at the Shawsheen Mill (American Woolen Company). If this were so, my brother and I would have been living with my grandparents at 34 South. St. [Lawrence, on the Andover town line]." Below: The Shawsheen Mills in Andover in 1977, right before they were turned into apartments. Source: Andover Historical Society "I’m pretty sure the next job my father had, during World War 2, was at the Tyer Rubber Company, on Railroad St. (where Whole Foods is now). I think he was a warehouse man. As I remember he did bring home pairs of rubbers and overshoes at times. I was then in grammar school" The Tyer Rubber factory eventually was owned by Converse. Soles for their famous Chuck Taylor sneakers were apparently produced there, along with NHL hockey pucks. Manufacturing ceased there in 1977, and by 1990 the facility had been converted into apartments. As of late, there is even a Whole Foods in the front part of the facility, showing how far the town of Andover in particular has come from its quasi-industrial past! Below: My grandfather's eminently respectable parents on the occasion of their fiftieth wedding anniversary in North Andover, Mass., 1954 "The next job I believe dad had was with the B&M Railroad. I believe Grandpa Johnson, a mechanic with the B&M at the South Lawrence round house got him the job. The job was as a mechanic assistant at the round house in Boston. So this entailed a daily round trip by train. He worked there until he got laid off when the job of assistant mechanic was eliminated altogether, this was probably when Diesel engines replaced steam engines and assistant mechanics were no longer needed. I also remember him not showing on time for supper a number of nights. This occurred when he fell asleep on the train and woke up at the last stop in Haverhill. Then he would have to take the train back to Lawrence which probably got him back home about an hour after his due time." Below: My grandfather posing with other relatives in front of one of the Johnson family cottages at Hampton Beach, New Hampshire in the mid- to late- 1940s. He is lying down in front. His final job was in North Andover, at the huge Western Electric factory that was built there after World War II. "Next he worked at the Western Electric Plant in North Andover until retirement. I’m not certain what kind of work he did there, now it comes to me, I think he was a clerk in a tool crib, if you know what I mean. In any case he liked the work as I recall." "There is one more job he had," my father added. "This was as a janitor in the building [in Andover] where Phillips Academy’s school course books were sold. Now I don’t remember if he held this job before he went to work for Western Electric or after he retired. In any case I believe he worked his butt off there. It was the only time lever heard him complain about his work. He was not there for long, as I remember." Below: Osgood Landing, North Andover (largely vacant). Formerly the Western Electric Merrimack Valley Works, then an Alcatel plant. Eagle-Tribune photo. I've been told I can work like a dog, uncomplainingly. Maybe I got it from my grandfather. Even though my grandfather was a "working stiff" (as my father calls him), he regularly wore a jacket and tie when he wasn't at work. I don't know if this was a generational thing, or whether he did it consciously in an attempt to maintain some dignity despite his fairly plebeian economic status. He liked to sketch figures, including nudes copied from Playboy (an excuse to buy the magazines despite the certain protests of my fairly prim and proper grandmother). He exhibited a lot of [unmet] artistic talent that I also seem to have inherited, which is also basically unmet. Except I at least got the luxury of drawing real life nudes, when I was in the eleventh grade at Phillips Academy. Another general point: My grandfather's work history - spanning employers in Lawrence, Andover and North Andover - illustrates the free flow of people throughout an economically integrated area. One of the themes of my blog is the formerly integrated nature of "Greater Lawrence" (meaning Lawrence, Methuen, Andover, North Andover and Salem N.H.). The separate "ghetto" status of Lawrence is only a thing of the last thirty years. My father's family lived all over the Greater Lawrence area. It all seems like it was, back in the day, one big integrated area, even into the late 1970s and in my own early memory. My genealogical line from William Brewster, spiritual leader of the Pilgrims, down to Edwin Ayer my great great grandfather, is as follows: Jonathan Brewster (1593 - 1659) son of William Brewster Ruth Brewster (1631 - 1677) daughter of Jonathan Brewster Mercy Pickett (1650 – d. New London, 1725) daughter of Ruth Brewster Samuel Fosdick (b. New London, 1684 – 1753 d. Charlestown)(buried Phipps cemetery) son of Mercy Pickett James Fosdick (b.1716 New London – d. 1784 Charlestown) (buried Phipps cemetery) son of Samuel Fosdick David Fosdick (b. 1757 Charlestown – d. 1812 Charlestown) (buried Phipps cemetery) son of James Fosdick Elizabeth Fosdick (b. 1791 Charlestown – d. 1855 Charlestown) daughter of David Fosdick Edwin Ayer (b. 1827 Charlestown – d. 1908 Lawrence). That's a lot of Fosdicks! What can I say about this clan (which, by the way, undermines my narrative that my ancestors arrived at the mouth of the Merrimack River and basically moved only 20 miles up river and then all stayed)? First point, the Fosdicks came to Charlestown, just north of Boston, and stayed there forever. So it's still North of Boston, meaning my basic claim holds up, that almost every American-born person from whom I'm descended was born North of Boston. I know of no ancestors born south of Boston except for the Fosdicks listed above, who moved to New London for just a few generations... probably to get away from insufferable puritans who ran Boston back then. They eventually moved back to Charlestown, however. So in my book, it's no harm, no foul! (Mr. Ayer above was of a Haverhill family; his father moved to Charlestown but he eventually moved back to Haverhill and married my great great grandmother Mary Jane Valpey of Andover, so I count him as being from the Merrimack Valley.) A couple of the Fosdicks in this list appear to have been n'er-do-wells. Stephen Fosdick (1583-1664), grandfather of Samuel Fosdick listed above, of Charlestown, Mass. was excommunicated from the puritan church for a period of twenty years, for crimes unspecified. How he got back into the good graces of the Elect is also not specified. His son John Fosdick (1626-1716) was charged with fornication by the Massachusetts authorities. “On 16 March 1649, John Fosdick, the constable of Charlestown was required (too was Ann the wife of Henry Branson) to appear at the next Court at Cambridge to answer for fornication committed by her with John Fosdick before she was married.” Despite this charge, he was allowed to remain constable, and served as a sergeant during King Philips War against the Indians in the 1670s. Another interesting thing is that, when I worked as a Park Ranger at Bunker Hill Monument in Charlestown, and lived in the Charlestown Navy Yard, I would walk to work past the Phipps Cemetery where all these Fosdicks are buried. Of course at the time, in 1994, I had no idea they were my ancestors! Anyway, my main challenge in proving lineage to William Brewster was that David Fosdick’s parent’s names were obliterated from the town birth records after the fact. Below: David Fosdick's entry in the birth records of Charlestown (circled in yellow). What happened that would cause the names of his parents (along with those of his wife's) to be obliterated from the town records?? One theory is that David Fosdick lost the family fortune - there were tales of a family "mansion" on the Charlestown neck, and hundreds of acres of land that were lost. How this happened, we don't know. Speculation in risky South Sea ventures? Ill-fated purchases of timberland in the wilds of northern Maine that got taken by the French? Investment in a merchant ship that didn't return from the Spice Islands? Anyway, I eventually surmounted this obstacle by obtaining the baptismal records for David Fosdick from the First (Congregational) Church of Charlestown. This involved my first physical research trip to conduct genealogical research, instead of just doing it online. At the magnificent facilities of the New England Historic Genealogical Society in Back Bay, I got my hands on a copy of these records. This was enough proof to satisfy the genealogist of the Mayflower Society that David Fosdick was indeed the son of James Fosdick listed above. Below: Baptismal records for David Fosdick, with a date corresponding to his birth date, and showing who his parents were. Thank god for my research that they weren't excommunicated at the time their son was born or this record would not exist. As a result of finding this evidence, my last document, the Mayflower Society genealogist accepted my application. A few months later, I received the certificate below.

Everyone in the Greater Lawrence area seems to know the story of the Bread and Roses Strike of 1912. It stands out for two reasons:

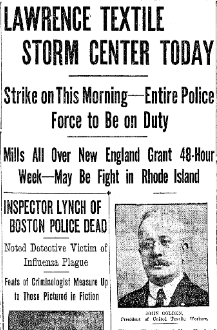

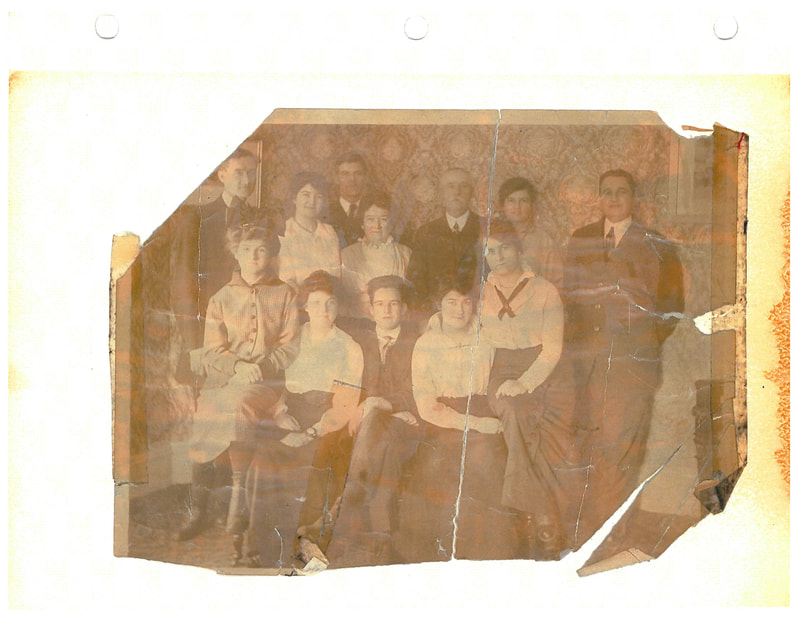

Below: Lawrence strike announced in the New York Times, February 3, 1919 How things had changed between 1912 and 1919 Even though the 1919 strike occurred only seven years after the 1912 strike, the world had changed in ways that made a successful strike of this kind more difficult.

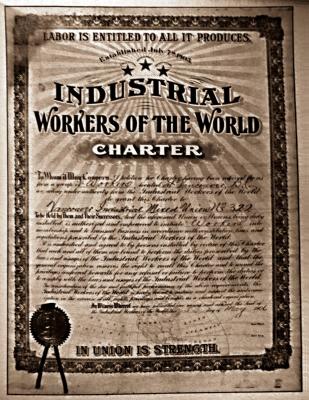

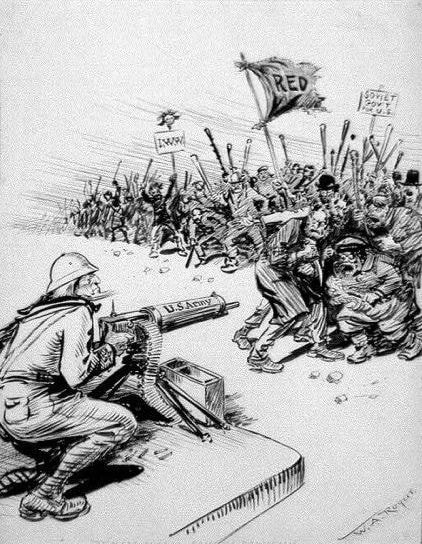

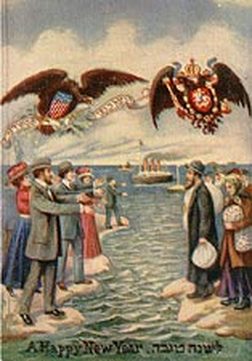

Below: The I.W.W. Charter, which reads in part "The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of the working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life." The Empire Strikes Back: The Red Scare and the Anti-Immigrant Political Climate H.L. Mencken summarized the political climate of 1919 in his book The American Scene. It was in sharp contrast to the climate in 1912, when unfettered immigration was widely tolerated because it fed the high demand of industry for cheap labor. “Returning servicemen found it difficult to obtain jobs during this period, which coincided with the beginning of the Red Scare. The former soldiers had been uprooted from their homes and told they were engaged in a patriotic crusade. Now they came back to find ‘reds’ criticizing their country and threatening the government with violence, Negroes holding good jobs in the big cities [until this time virtually no blacks had moved to northern cities], prices terribly high, and workers who had not served in the armed forces striking for higher wages. A delegate won prolonged applause from the 1919 American Legion Convention when he denounced radical aliens, exclaiming “Now that the war is over and they are in lucrative positions while our boys haven’t a job, we’ve got to send those scamps to hell.” The major part of the mobs which invaded meeting halls of immigrant organizations and broke up radical parades, especially in the first half of 1919, was comprised on men in uniform….” “As the postwar movement for one hundred percent Americanism gathered momentum, the deportation of alien nonconformists became increasingly its most compelling objective. Asked to suggest a remedy for the nationwide upsurge in radical activity, the Mayor of Gary Indiana, replied, ‘Deportation is the answer, deportation of these leaders who talk treason in America and deportation of those who agree with them and work with them.’ ‘We must remake America,” a popular author averred, ‘We must purify the source of America’s population and keep it pure…We must insist that there shall be an American loyalty, brooking no amendment or qualification.’ As [one writer] noted, ‘In 1919, the clamor of 100 percenters for applying deportation as a purgative arose to a hysterical howl…Through repression and deportation on the one hand and speedy total assimilation on the other, 100 per centers home to eradicate discontent and purify the nation.” “The man in the best political position to take advantage of the popular feeling, however, was Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. In 1919…only Palmer had the authority, staff and money necessary to arrest and deport huge numbers of radical aliens. The most virulent phase of the movement for one hundred percent Americanism came early in 1920, when Palmer’s agents rounded up for deportation over six thousand aliens and prepared to arrest thousands more suspected of membership in radical organizations. Most of these aliens were taken without warrants, many were detained for unjustifiably long periods of time, and some suffered incredible hardships. Almost all, however, were eventually released.” Given this climate of suspicion and hostility toward recent immigrants, a strike by unskilled workers from perhaps two dozen ethnicities in Lawrence would seemed destined to fail! Below: Anti-I.W.W. propaganda showing a machine-gun wielding doughboy holding off an unruly mob of foreigners. Opportunity for the Lawrence Immigrant Workers and the Reaction of the Authorities Opportunity In late 1918, the United Textile Workers of America (an A.F.L. union that mainly represented the skilled workers such as loom fixers) negotiated a reduction in the work-week in Lawrence to 48 hours. However, the deal not to reduce pay at the same time seems only to have applied to skilled workers. “In that climate of flexibility and accommodation it seems as if the Lawrence manufacturers, and the American Woolen Company in particular, wanted to discredit the unions altogether. At the very least they seemed to have wanted the workers to absorb the cost of the slack time of postwar reconversion.” (Source: Province of Reason, by Sam Bass Warner, Jr. (1988)) In other words, the management and the skilled workers colluded to pass the slack in production onto the unskilled loom operators by cutting their hours and their pay. The workers, sensing a déjà vu of what happened in 1912, when hours also were cut along with pay, went on strike. “On 3 February 1919, between 17,000 and 30,000 immigrant workers walked out of mills throughout Lawrence and began the ‘54-48’ strike. The strikers organized themselves among …different ethnic groups, with one leader per group. In addition, the strikers invited three pastors, known collectively as the Boston Comradeship (Anthony J. Muste, Cedric Long, and Harold Rotzel) as spokespeople. Ethnic stores and businesses supported the strikers by accepting coupons in place of cash. Meanwhile, the strikers boycotted stores that did not support the strike.” (From “Lawrence Mill Workers strike against wage cuts, 1919” by Kerry Robinson 16/02/2014; appearing on the site Global Nonviolent Action Database https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/lawrence-mill-workers-strike-against-wage-cuts-1919, retrieved February 10, 2018) Like the 1912, it was a strike of immigrants, by immigrants. “The general strike committee meets every morning in a dingy hall—the home, evidently, of a Syrian religious society [presumably the Marionite church?]. Approximately forty delegates come to this hall from the various language groups. Within its four walls, incontinently displaying faded pictures illustrating the Book of Revelation, Lawrence has formed her league of nations. That Syrian religious stronghold is vibrating with a new eloquence. New emotions, some of them powerful and portentous, are coming to unheralded expression. The hostile races are now allies.” (Source: Swing, Raymond. “The Blame for Lawrence.” The Nation magazine, April 26,1919.) Reaction The strike was dismissed by the A.F.L. as an unlawful “wildcat” strike. Therefore, the very union that negotiated the reduction in hours, the United Textile Workers, did not lead the strike. The walkout was covered by the mainstream press in hysterical terms involving “reds”, “commies” and “foreign anarchists”. The smelly, funny dressing, foreign-language-speaking strikers were seen as the vanguard of wild-eyed Bolsheviks. A Committee of Public Safety was organized, headed by Peter Carr, who had been a patrolman in the 1912 strike. He said “Lawrence is a city of 100,000 population and thirty-three different nationalities, most of whom are foreign. We feel this is a fertile field for the implanting of Bolshevist propaganda, and as American citizens it is our duty to suppress it.” (Source: Warner, cited above.) In other words, the response to the strike must be quick and fierce. Below: Photo of the Machine Gun used by Lawrence police to intimidate strikers, May 5, 1919. “The city administration of Lawrence enacted an aggressive approach against the strikers. Mayor John Hurley immediately began inviting in police from other towns. In less than a week, the city banned mass gatherings, restricted news coverage of the strikers, regulated inter-city travel, and kept the mills under constant police surveillance. After several cases of police beating strikers at the picket line and pro-mill infiltrators encouraging the strikers to react violently, the Boston Comradeship decided to join the picket line. At first, the presence of the clergymen deterred violent police action, but soon the police grew more intense. In one instance, several policemen cut off Muste and Long from the picket line, trapped them in an alley, beat them both, and arrested them for inciting a riot. A judge acquitted them a week later. On 18 February, a coalition of women strikers sent an appeal to Governor [later President] Calvin Coolidge to investigate excessive police brutality. Coolidge refused to meet with the coalition and sent a letter written by his secretary in defense of the local authorities’ actions. On 21 February, when a group of about 3000 strikers met in an open area near a garbage dump, two squads of police beat and then arrested strikers and injured several unaffiliated bystanders. The district court judge sided with the police and placed heavy fines on those arrested. After a lull in police violence, hostilities escalated again when the city received a machine gun from an unnamed source on 5 May to use against strikers. The machine gun was never used, but prominently displayed in front of the picket lines for intimidation. The next day, a group of men kidnapped two immigrant strike leaders, Anthony Capraro and Nathan Kleinman and left them beaten and disheveled in [Lowell].” (Source: Robinson, cited above) Were the immigrant strikers from southern and eastern Europe Bolsheviks, or was something else going on? A contemporary commentator from April 1919 explained the real story of the poor immigrant workers from places like Italy, Poland, the Balkans and Syria. “The fact that the strikers are foreigners divided among thirty-one nationalities, that few of them speak English or are citizens, and that some are boasting that in a short time the workers will own the mills, has been used as an argument that this is an attempt on the part of Eastern Europeans to impose upon America the fallacious economics of a misguided Russia. And in the light of this argument the hostility of the community, the shocking conduct of the police, and the obstinacy of the manufacturers are being justified. But the motives of the strike are not to be so precisely named or so conveniently dismissed. Had these foreigners swarmed to America imbued with the revolutionary spirit, and intrenched themselves in an industrial city to launch an attack, this strike would be truly a breach of hospitality. But they are here because American business demanded cheap labor, and many of them were even solicited by textile agents. For years the textile manufacturers have carried on a policy of gathering in the peasants of Eastern and Southeastern Europe to operate the looms of New England. These immigrants were distributed so that no more than fifteen per cent. of any one race were employed in a single mill, and the apportionment was dispassionately determined so that men and women racially hostile to one another worked side by side. This was to render organization impossible, and thus keep wages low.” (Source: The Nation article, cited above.) In other words, these workers were induced to come here because they would provide cheap labor, and their ethnicity and foreignness was used to keep them weak. Amazingly, the American Woolen Company, the main textile manufacturing company in Lawrence, had a direct hand in inviting such workers that they now faced at the picket line. “The American Woolen Company, which owns four of the eight Lawrence mills, posted lithographs throughout the Balkans depicting one of their factories as a magnificent edifice, a veritable palace of Midas, through one portal of which an army of ragged peasants marched, only to emerge from a neighboring doorway splendidly arrayed and bearing trophies—an unparalleled vision of instantaneous American alchemy. Unfortunately, actualities and visions are not allied. In red brick factories, one prodigious tier of glazed windows upon another, the European peasant has tended the looms and the spindles, and has received at the end of the week less than a living wage. The Lawrence manufacturer has not so much as justified the first unwritten premise of his posters; he has done nothing comprehensive to make Americans of these disillusioned immigrants.” (Source: The Nation article) I would really like to get my hands on a copy of the false advertising pamphlets, presumably published in Italian, Croatian, Serbian, Polish and all manner of other languages and distributed in poor rural regions to attract workers to Lawrence, where they would be kept in ethnic ghettos unable to organize with other groups of workers. Below: Poster encouraging immigration to America aimed at Russian Jews (if I can find something more on point, I will replace it) Return of the Jedi: Victory for the Strikers The immigrant workers, many of whom had been lured to Lawrence by suggestions of a better life by the employers against whom they now struck, triumphed over the Red Scare prejudices of the day and the direct hostility of the authorities. According to Robinson, cited above: “In early April, Governor Coolidge forced state arbitration between the strikers and the mill owners. The hearings held by the State Board of Arbitration and Conciliation lasted for nearly a month, but they did not lead to a compromise. However, these hearings marked the first time since the strike began that both sides directly communicated with each other. Seeing an opportunity to share credit for the resolution of the strike, the United Textile Workers [remember them??] reappeared in mid-May and negotiated with mill owners without the knowledge of those involved in the strike. The union secured a 48-hour work week as well as a 15% wage increase, more than the 12.5% increase the strike demanded. The mill owners accepted the terms since they were in need of workers and did not wish to negotiate with the strikers. Meanwhile, the strike had run out of funding. After weeks without monetary relief for strikers, organizers were ready to announce the strike as a failure. On 19 May, just as Muste prepared to announce the end of the strike, the mill owners called him to the conference with the UTW and explained the new agreement. Muste and the other organizers added a non-discrimination clause allowing the strikers to claim their former jobs. The mill owners accepted the conditions, and on 20 May 1919 the strike ended.” Above: My great grandparents Michael McDonnell and Theresa Doherty McDonnell and some of their children (with spouses), including my grandfather Joseph McDonnell standing next to and behind his mother. Michael owned a meat market and Theresa ran a boarding house across from the Arlington Mill. Michael was born in Lawrence in 1851 on Elm Street, his parents later ran a boardinghouse up Broadway just over the town line in Methuen. My grandfather was born in 1889 at a house on Broadway that straddled the Spicket River, where the little bridge is. Theresa was born in Manchester England where her parents had gone to work in the mills. Her father brought his family over from Manchester England to Lawrence by receiving $600 for fighting in the place of two different men in the Civil War in 1863. Unfortunately he never came back from that war, rather he lived out his days as an invalid in a military hospital in Bangor Maine. I think this picture was taken around 1920.

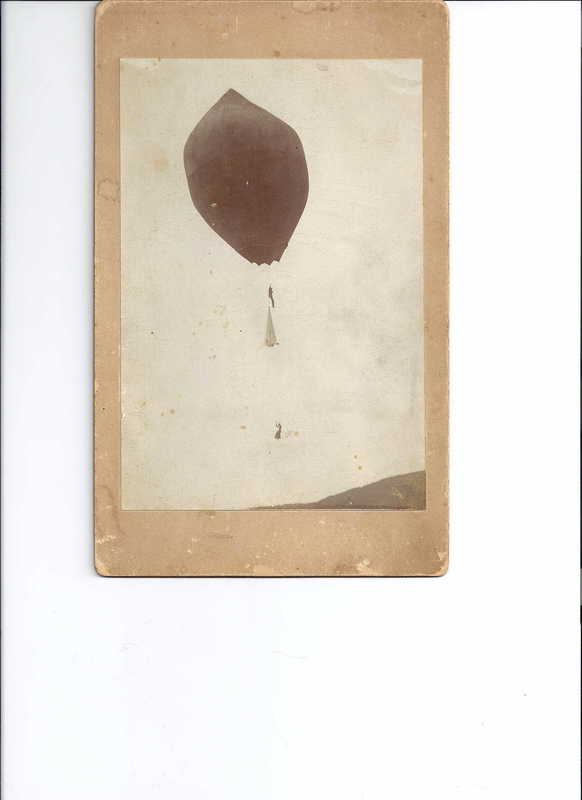

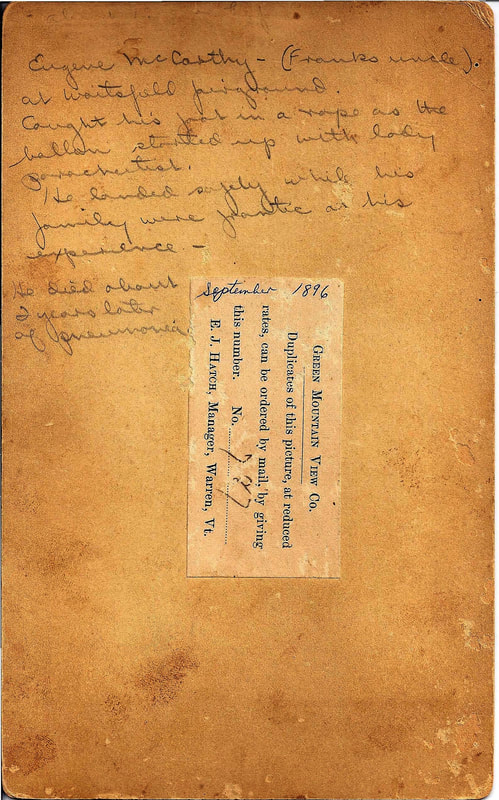

Below: The bridge where my grandfather's birthplace, 541 Broadway, used to be. Photos by me, 2016. Above: Photo of "Lady Parachutist" and Eugene McCarthy, caught in the lines of a hot air balloon and carried aloft at a country fair, Waitsfield Vermont, September 1896